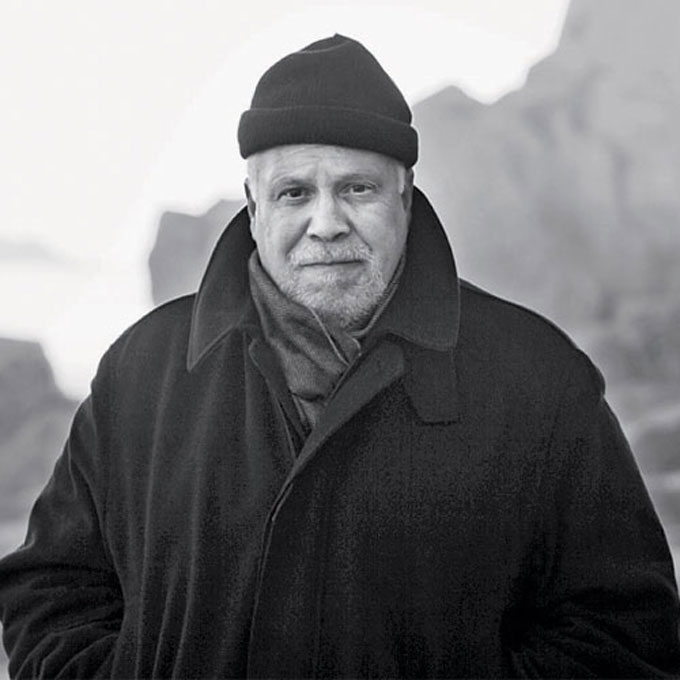

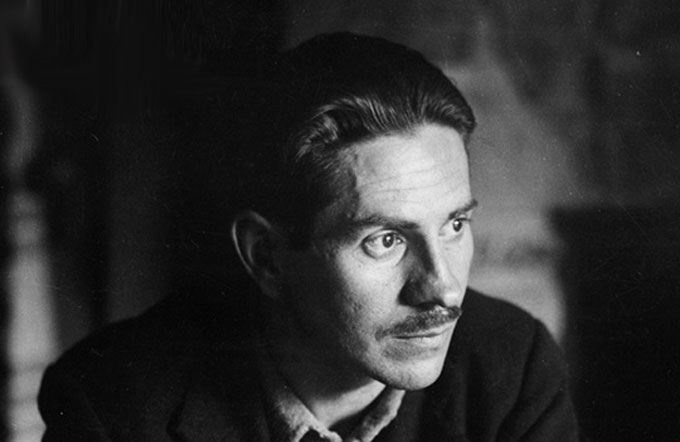

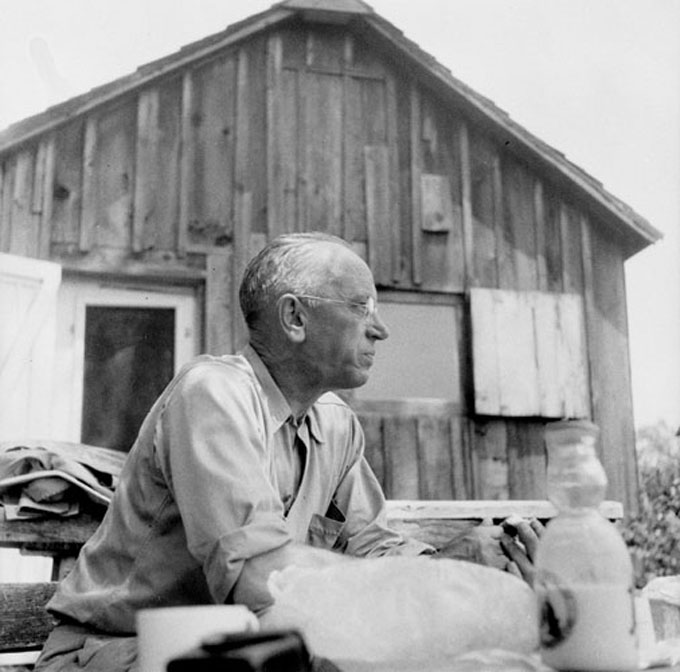

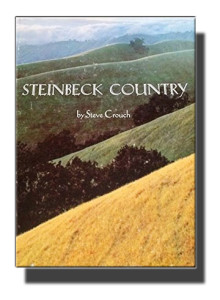

A few days ago I bought a second copy of Steve Crouch’s 1973 photography book Steinbeck Country from a young man in financial trouble, the only reason I made the purchase. That evening I glanced at several chapters. They were powerful and prescient (“ . . . the seeds of desperation are at hand. They may already have been planted.’’), and I had to keep reminding myself that the book wasn’t written by John Steinbeck. Why I had it in my head that Steve Crouch–a top-tier photographer–shouldn’t be a fine writer as well, I have no idea.

Steve Crouch–a gentleman I knew only slightly–seemed to have absorbed some of John Steinbeck’s style and love for Monterey County. Each of the 20 chapters of his book leads off with a quotation from Steinbeck’s writing, and the chapter titles (“The Farmers,” “The Spanish,” “The River Valley,” “The Mountains”) have Steinbeck’s simplicity. One—“The Mexicans—is especially relevant to the threats made against the nation’s Mexican-American population in the recent presidential campaign.

I met Steve when I was a reporter at the Monterey Herald, where he would occasionally take on freelance assignments. I don’t know whether he was ever a staff member, but I recall seeing him in 1973, not long after Steinbeck Country had been published by American West Publishing Company of Palo Alto. I recall Steve smiling shyly and scratching the back of his head when someone stopped to compliment him on the book, as if the book’s success had come as a complete surprise to him. I wasn’t into Steinbeck yet, and my interest in the book at the time was simply for its exquisite photography. If I could go back I’d ask him about the people and places he discovered during his travels around Monterey County, his meetings and relations with the people and the land celebrated by John Steinbeck in The Pastures of Heaven, Cannery Row, and East of Eden.

I met Steve when I was a reporter at the Monterey Herald, where he would occasionally take on freelance assignments. I don’t know whether he was ever a staff member, but I recall seeing him in 1973, not long after Steinbeck Country had been published by American West Publishing Company of Palo Alto. I recall Steve smiling shyly and scratching the back of his head when someone stopped to compliment him on the book, as if the book’s success had come as a complete surprise to him. I wasn’t into Steinbeck yet, and my interest in the book at the time was simply for its exquisite photography. If I could go back I’d ask him about the people and places he discovered during his travels around Monterey County, his meetings and relations with the people and the land celebrated by John Steinbeck in The Pastures of Heaven, Cannery Row, and East of Eden.

Steve’s intimate familiarity with Monterey County is evident in a chapter called “The Wind.” No one can write about the Salinas Valley convincingly without writing about the wind, and Steve experienced its harshness when he photographed farm laborers: “The people who work in the fields come prepared against the wind, muffled to the eyes, for the wind can cut to the bone. Men riding the tractors resemble Bedouins of the desert.’’ I experienced the same winds, though less painfully, in my job as a reporter. For instance, while covering a high school baseball game in the valley one day, I witnessed a player throw his cap in anger. The afternoon wind blew the cap high up onto the backstop and, roaring, held it there for the entire game, several hours. It ripped pages from my reporter’s notebook. Imagine what it could do to stoop laborers, men and women, cutting lettuce heads.

The people who work in the fields come prepared against the wind, muffled to the eyes, for the wind can cut to the bone. Men riding the tractors resemble Bedouins of the desert.

In “The Mexicans” Steve quotes To a God Unknown, then tells the story of the legendary bandit Tiburcio Vasquez, a kind of Latin Robin Hood who died in 1875 at the end of a rope. Though honored in memory by many Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, Vasquez may not have been Mexican at all: “[I]n those days of ‘the only good Indian is a dead Indian,’ it was also said that ’the only good Mexican is a dead Mexican.’” Of mixed blood, Tiburcio Vasquez “was too dark ever to be taken for Anglo-Saxon,” and Anglo migrants from the East were moving in on Monterey County’s Mexican-Americans. “That his cause was hopeless did not matter,” Steve writes. “[W]hat was important was that he provided a champion for the Mexicans when they needed one.’’

Tiburcio Vasquez, a Latin Robin Hood who died in 1875 at the end of a rope, was a champion for the Mexicans when they needed one.

Moving on to the field worker strikes of the 1960s and 70s, Steve points to another form of Mexican-American displacement: “Mexicans who live on the farms are moving away, displaced by machines. Most of them have become permanent residents of the valley towns . . . . When they do work, the pay is good, particularly when a complete family works—and Mexican families often muster as many as eight or ten to work.” Reporting from Salinas, I saw instances where this ethic could be detrimental. For instance, there was a basketball coach at Alisal High named Jim Rear. Season after season he brilliantly coached a group of short (for basketball) Mexican-American players into smart, winning teams. When labor was needed some parents pulled their sons from the team to work in the fields, perhaps costing their children academic advancement or college scholarships in return for not much, but necessary, family money. Several players, some of them fine students, told me that their parents failed to see the need for extra school activities—including sports—when the boys could be earning money in the fields.

When they do work, the pay is good, particularly when a complete family works—and Mexican families often muster as many as eight or ten to work

After Steve died in 1984, the late photographer Al Weber saved his work from a trip to the dump. Steve’s book has become a classic, and his photos of John Steinbeck’s Monterey County are now part of the special collection at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The second copy of Steinbeck Country I bought was inscribed by a woman named Rosalind to a man named Larry, who “introduced me not only to Steinbeck, but to so many of the beauties within the pages of this book. May `Steinbeck Country’ bring you some of the pleasure and joy you have brought me.‘’

Steve Crouch must have liked that. I think Steinbeck would too.

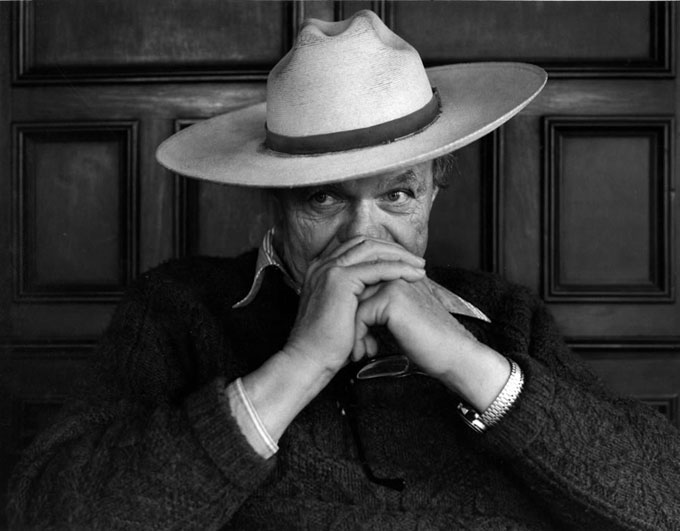

Photograph of Steve Crouch @Martha Casanave.