San Jose State University’s Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies continues four decades of distinguished service to scholars, teachers, and students with John Steinbeck: A Writer’s Vision. The recently released video was written by Susan Shillinglaw and produced by the Center’s staff, led by Peter Van Coutren, the Center’s curator. Tracing Steinbeck’s life and work from Salinas, California to New York City and beyond, the 16-minute video uses photographs and recordings from the Center’s extensive collection—as well as voice over designed to sound as old as Steinbeck himself—to summon the period and personality that gave rise to Steinbeck’s greatest fiction. A follow up video is in preparation, about John Steinbeck, Woody Guthrie, and The Grapes of Wrath.

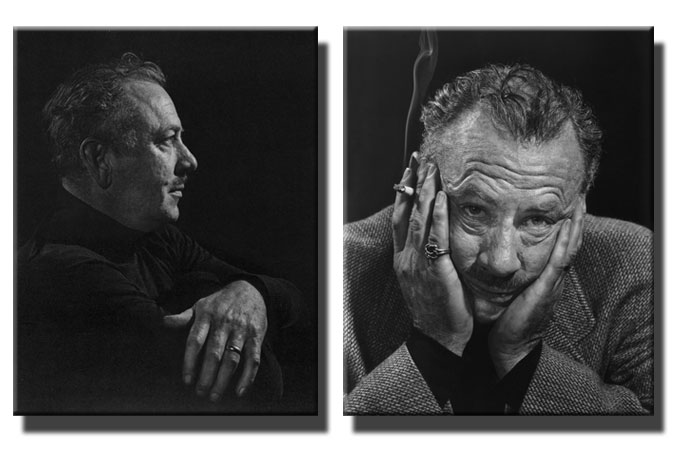

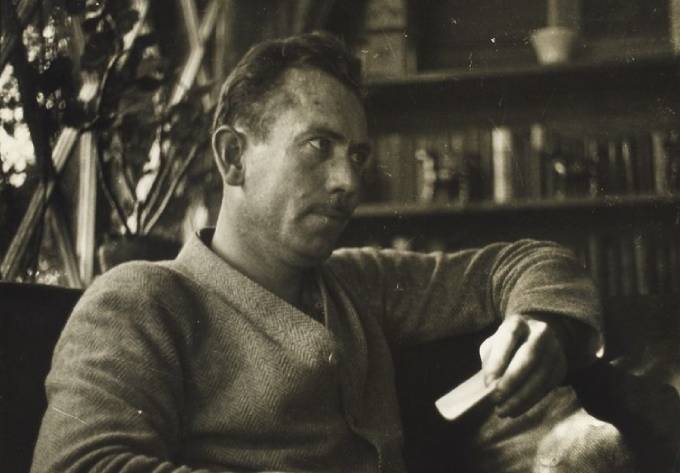

Portrait photos of John Steinbeck by Yousuf Karsh courtesy of the Karsh Foundation.