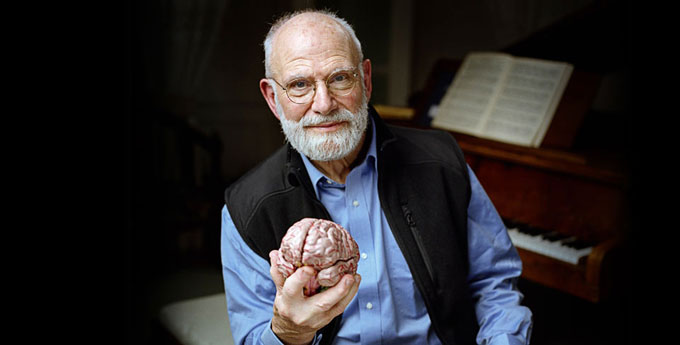

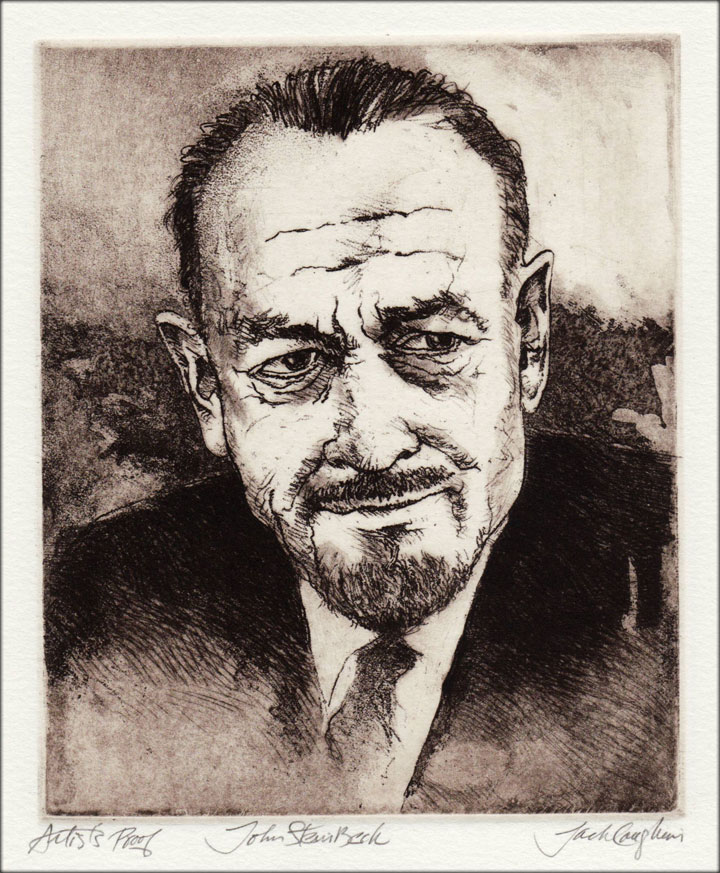

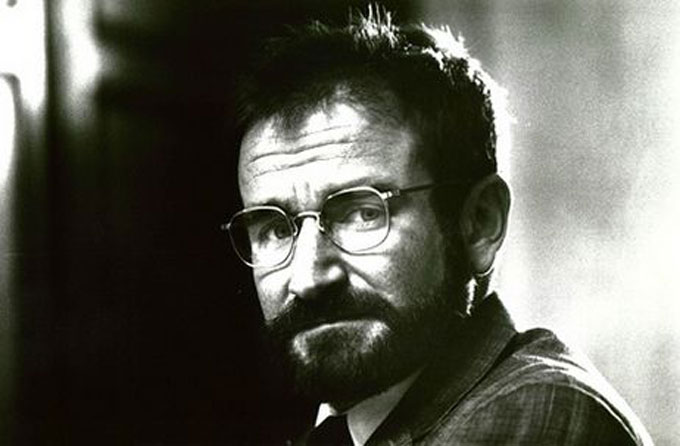

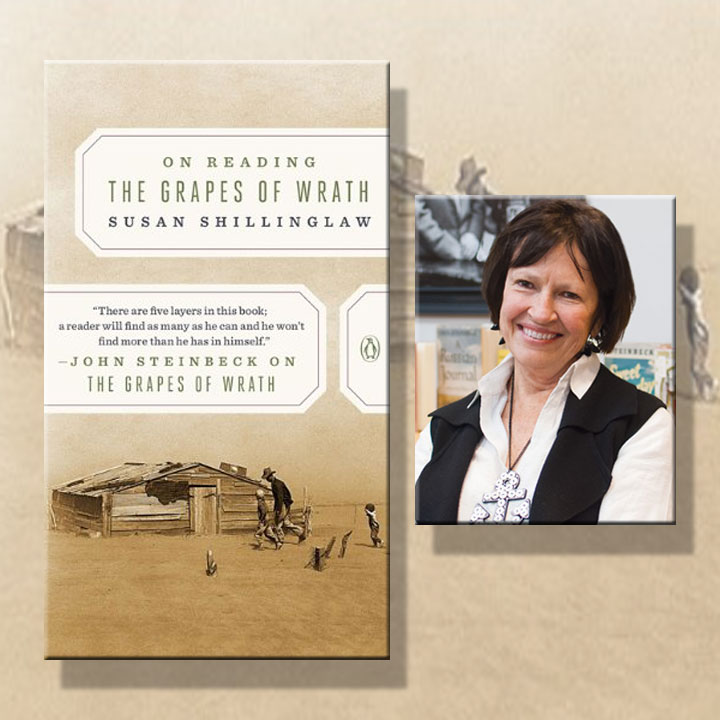

The literary neuroscientist Oliver Sacks will be 82 next month. Robin Williams, who portrayed Sacks in the 1990 film Awakenings, would be 64 in July if he were still alive. Like John Steinbeck, both men broke boundaries in inspired work that defied convention, created controversy, and kept wowing the public year after year. Luckily, Sacks has written a memoir—On the Move: A Life—that will please fans of Sacks, Robin Williams, and John Steinbeck, whose novel Cannery Row moved Sacks to consider becoming a marine biologist as a boy in post-World War II England.

Sacks became a doctor instead, but he emulated Steinbeck by also becoming a bestselling writer—so brilliantly that he’s been described as the poet laureate of medicine. Migraine, his first book, was published in 1970. The next, Awakenings, appeared in 1973. It was adapted as an Oscar-nominated movie starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro in 1989 and helped make Oliver Sacks a synonym for science you can understand.

Oliver Sacks became a doctor, but he emulated John Steinbeck by also becoming a bestselling writer—so brilliantly that he’s been described as the poet laureate of medicine.

Since Awakenings, Sacks has written more books and hundreds of articles about the miracles, mysteries, and malfunctions of the human brain, his specialty. Like Steinbeck, he records real life in his writing, narrating clinical case histories with the compelling power of the best fiction. Also like Steinbeck, he’s autobiographical by nature, and his case histories frequently include himself. Migraine grew out of his personal experience with the debilitating condition, which I learned from my former boss Dr. William Langston—author of The Case of the Frozen Addicts (1995)—is common among neurologists.

Like Steinbeck, he records real life in his writing, narrating clinical case histories with the compelling power of the best fiction.

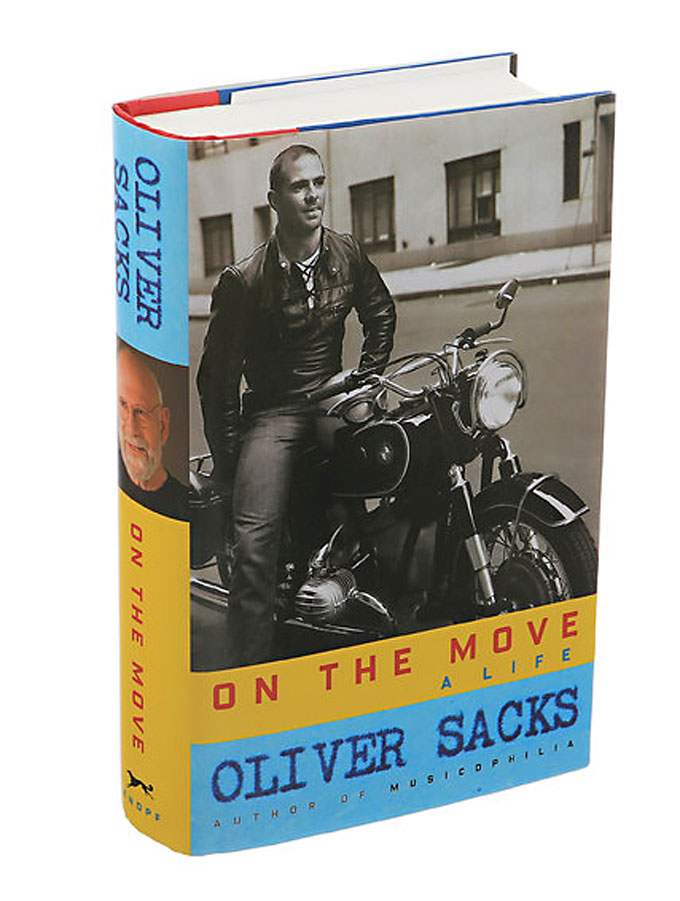

An avid motorcyclist addicted to speed, Oliver Sacks wrote A Leg to Stand On (1984) after losing the awareness of one of his legs following an accident. A music lover who plays the piano, he wrote Musicophilia (2007) about patients with unusual musical obsessions. When cancer cost him sight in one eye he wrote The Mind’s Eye (2010), an amazing account of the ways in which visually impaired people perceive and communicate. Six months ago he learned that the cancer has spread to his liver. On the Move may be his last book.

In the first chapter Sacks recalls reading John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row as a teenager attending school outside London, where his parents and uncles practiced medicine. (Two of his brothers became doctors; a third, also brilliant, is bipolar.) After graduating from Oxford and finishing his medical training, he left England for America, where he has treated patients, taught, and written since 1960. He interned in San Francisco and completed his residency at UCLA during the period when John Steinbeck was writing The Winter of Our Discontent, Travels With Charley, and America and Americans. Though On the Move doesn’t mention meeting Steinbeck, it details Sacks’s friendship with other writers, including the poets W.H. Auden and Thom Gunn— gay men who, like Sacks, left England for the sexual freedom of San Francisco and New York.

In the first chapter Sacks recalls reading John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row as a teenager attending school outside London.

Like John Steinbeck, Oliver Sacks bloomed in California, falling in love with San Francisco, living in Los Angeles, and exploring Baja California in his travels and writing. Like Steinbeck, Sacks was influenced by the California writer Jack London, whose People of the Abyss provided a working title for the book that became Awakenings. Like Steinbeck and London, he was attracted to drugs and alcohol, suffered from depression, and found healing in the act of writing. In 1968, the year Steinbeck died, Sacks encountered the book that inspired Awakenings—A.R. Luria’s Mind of a Mnemonist: “I read the first thirty pages thinking it was a novel. But then I realized that it was in fact a case history—the deepest and most detailed case history I had ever read, a case history with the dramatic power, the feeling, and the structure of a novel.”

Like Steinbeck and Jack London, Sacks was attracted to drugs and alcohol, suffered from depression, and found healing in the act of writing.

Like Steinbeck, Sacks eventually left California for New York, where he saw patients at Beth Abraham Hospital, began writing for the New Yorker, and ended up teaching at a succession of star schools, including Columbia, New York University, and Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The true story told by Sacks in Awakenings unfolded at Beth Abraham, where comatose patients suffering from an extreme form of parkinsonianism caused by encephalitis lethargicus responded dramatically when treated with the drug L-dopa. Among them was “Lenny L,” the patient played by Robert De Niro in the movie adaptation of Awakenings. Robin Williams played Oliver Sacks, the story’s empathetic neurologist-narrator—what John Steinbeck called the authorial character found in any good novel.

The movie brought the author and the actor together in much the way John Steinbeck met Burgess Meredith and Henry Fonda 50 years earlier. Sacks reacted to Williams as Steinbeck did to Fonda—with awe. Before the filming of Awakenings began, Williams and Sacks visited a geriatric ward “where half a dozen patients were shouting and talking bizarrely all at once. Later, as we drove away, Robin suddenly exploded with an incredible playback of the ward, imitating everyone’s voice and style to perfection. He had absorbed all the different voices and conversations and held them in his mind with total recall, and now he was reproducing them, or, almost, being possessed by them.”

Then Williams began imitating Sacks, too—“my mannerisms, my postures, my gait, my speech—all sorts of things of which I had been hitherto unconscious.” The experience, says Sacks, was uncanny and a bit uncomfortable, “like suddenly acquiring a younger twin.” As On the Move reveals, however, the real Ed Ricketts figure in Sacks’s life wasn’t Robin Williams but Stephen Jay Gould, the evolutionary biologist and science popularizer who died from cancer, age 60, in 2002. Gould’s version of non-teleology, the idea dramatized by Steinbeck in Cannery Row, is called contingency, a concept drawn from modern sociobiology that would have appealed to Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck.

The real Ed Ricketts figure in Sacks’s life wasn’t Robin Williams but Stephen Jay Gould, the evolutionary biologist and science popularizer who died from cancer, age 60, in 2002.

Like Steinbeck, Oliver Sacks as a writer engages me for personal reasons. I read Awakenings when my mother was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in her 70s. I read Musicophilia with the curiosity of an amateur pianist, a trait I share with Steinbeck and Sacks. I read Sacks’s earlier memoir, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001), while working for The Scripps Research Institute. There I met another hero of On the Move, the neuroscientist Gerald Edelman, who graciously autographed my copy of his wonderful book Wider Than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness (2004). Edelman, a violinist and Nobel Laureate, was suffering from Parkinson’s, another link. The final pages of On the Move are devoted to Edelman’s elegant insights (“Every perception is an act of creation”), dissecting Edelman’s metaphor of a musical ensemble to explain how our minds work through reentrant signaling, the complex process that “allows the brain to categorize its own categorizations.”

The final pages of On the Move are devoted to Gerald Edelman’s elegant insights, dissecting Edelman’s metaphor of a musical ensemble to explain how our minds work.

Like Robin Williams, Gerald Edelman died in 2014, while Oliver Sacks was writing On the Move, and Edelman’s string quartet metaphor seems a good way to end this review. As an artist Sacks, like Williams, is more virtuoso than ensemble member. As a writer, like Steinbeck he’s a restless experimenter, constantly on the move between the worlds of art and science. Williams’s genius was visual mimicry, verbal speed, and comic improvisation. Oliver Sacks’s great gift—like John Steinbeck’s—is telling stories that explore the depths of suffering and the heights of hope in words anyone can understand. It’s sad that On the Move may be his last book, but a joy to celebrate his birthday. Five stars for On the Move and a toast to Oliver Sacks!

Oliver Sacks died at his home in Manhattan on August 30, 2015. On the Move topped the list of the year’s best books compiled by Brain Pickings.—Ed.