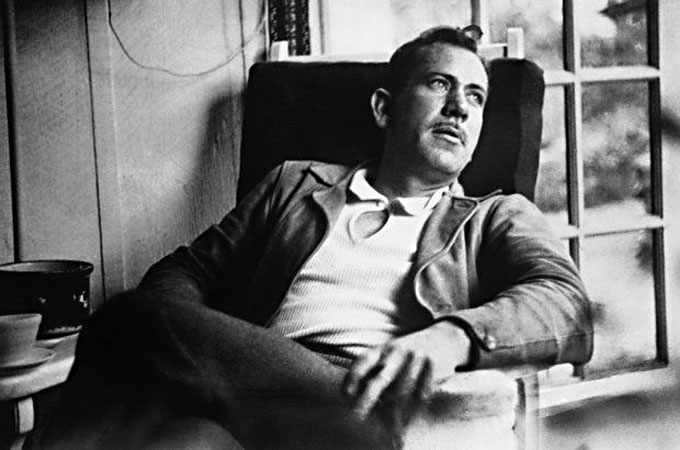

According to a report from the Associated Press, “The Supreme Court is leaving in place a decision awarding the late John Steinbeck’s stepdaughter $5 million in a family dispute over abandoned plans for movies of some of Steinbeck’s best-known works.” On October 5 “the high court said it would not take up the dispute involving the Nobel Prize-winning author’s stepdaughter Waverly Kaffaga, his late son Thomas Steinbeck and his daughter-in-law Gail Steinbeck.”

This outcome was predicted by observers following the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a vigorous advocate for extending creative copyright protections beyond existing limits. For readers unfamiliar with the background of the story, here is the full text of the AP report:

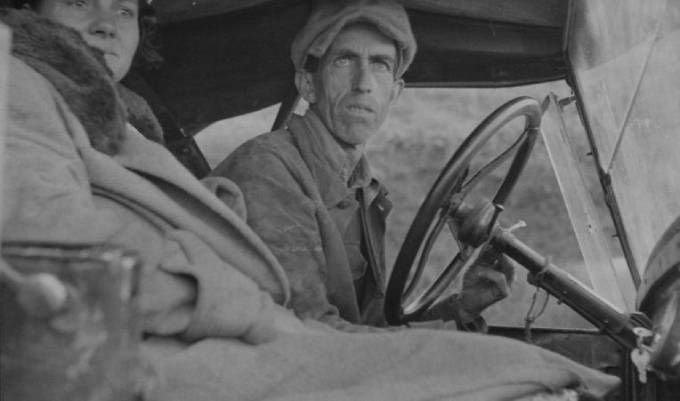

The author of “The Grapes of Wrath” died in 1968 and legal wrangling among his heirs has continued for decades. When he died, Steinbeck left the vast majority of his estate to Kaffaga’s mother Elaine, his third wife. Each of his two sons got $50,000. Legal wrangling ensued and has continued despite agreements between the parties over royalties and control of Steinbeck’s works. In the case the Supreme Court declined to get involved in, Kaffaga alleged that Thomas Steinbeck and his wife had continued to claim various rights in Steinbeck works despite losses in court. That, she said, led multiple Hollywood producers to abandon negotiations with her to develop screenplays for remakes of “The Grapes of Wrath” and “East of Eden.” A jury in Los Angeles awarded her a total of $13 million and an appeals court upheld the verdict in 2019 but struck down $8 million in punitive damages.

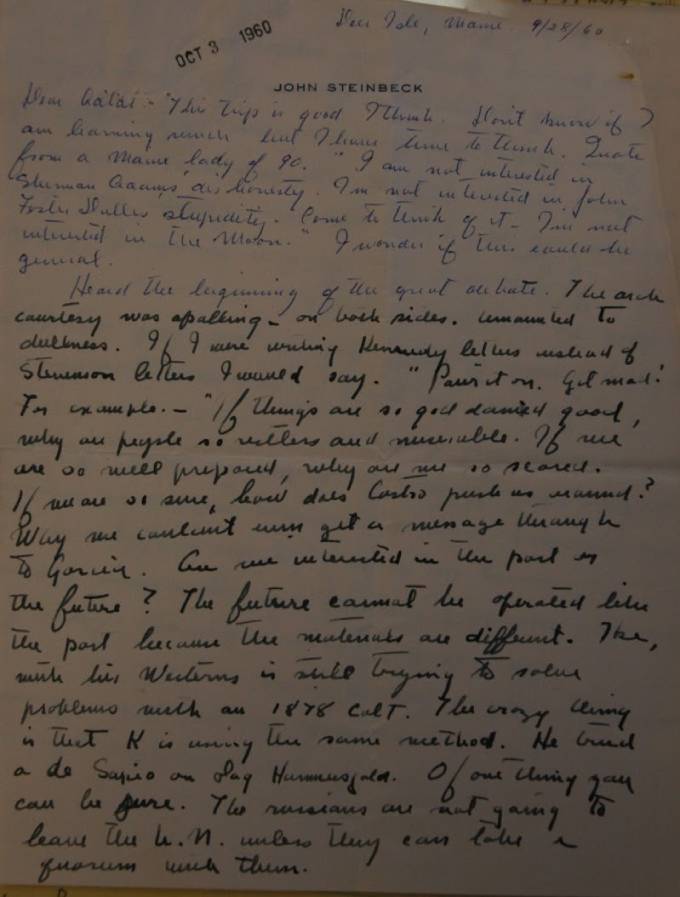

Photograph courtesy of the New York Times.