The word pajaro means bird in Spanish, and Central California’s Pajaro Valley may have inspired the setting of John Steinbeck’s 1936 American strike novel, In Dubious Battle. But the town of Pajaro, California, in Monterey County—the setting of so much great literature by Steinbeck—seems closer in spirit these days to the rained out world of the Joads at the end of The Grapes of Wrath.

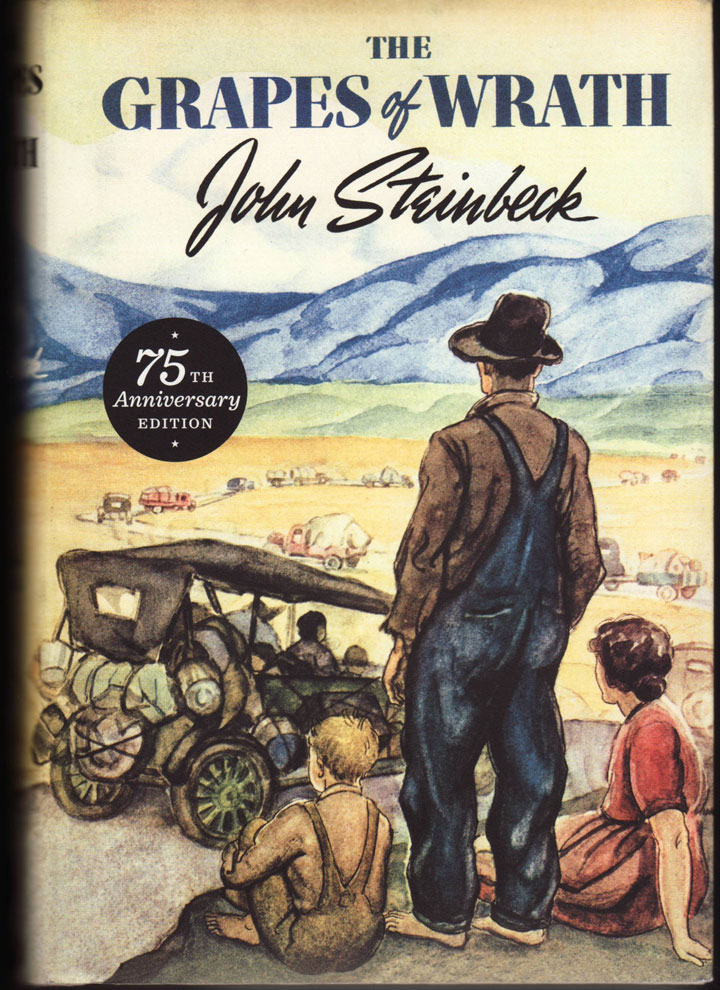

In these tough times for Pajaro, it’s good to remember that the artist who painted the cover image of Steinbeck’s 1939 novel was born there in 1889. His name was Elmer Stanley Hader, and, like Steinbeck, he knew hard times in California. He survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, and he was alert to the field labor strife dramatized in Steinbeck’s fiction. His portrait of the Joad family—tired and tattered, overlooking California for the first time—takes its power, like Steinbeck’s masterpiece, from its empathy.

Like Steinbeck, Hader moved on from Monterey County. He pursued his art career, first in San Francisco, then in Paris and New York. His illustrations appeared in national magazines including Cosmopolitan, and he collaborated with his wife Berta in creating more than 30 children’s books and in illustrating many others. Together they won the coveted Caldecott Medal for their 1949 children’s picture book, The Big Snow. His painting for the Grapes of Wrath cover eventually sold for more than $60,000. He died five years after Steinbeck, in 1973. Both men passed away in New York, but neither forgot his California roots. Each would have profound sympathy for Pajaro today, flooded out by The Big Rain of 2023.

Like Steinbeck, Hader moved on from Monterey County. He pursued his art career, first in San Francisco, then in Paris and New York. His illustrations appeared in national magazines including Cosmopolitan, and he collaborated with his wife Berta in creating more than 30 children’s books and in illustrating many others. Together they won the coveted Caldecott Medal for their 1949 children’s picture book, The Big Snow. His painting for the Grapes of Wrath cover eventually sold for more than $60,000. He died five years after Steinbeck, in 1973. Both men passed away in New York, but neither forgot his California roots. Each would have profound sympathy for Pajaro today, flooded out by The Big Rain of 2023.

Lead image courtesy Los Angeles Times. For more on the subject, read “How a long history of racism and neglect set the stage for Pajaro flooding” in the paper’s March 20, 2023 edition.