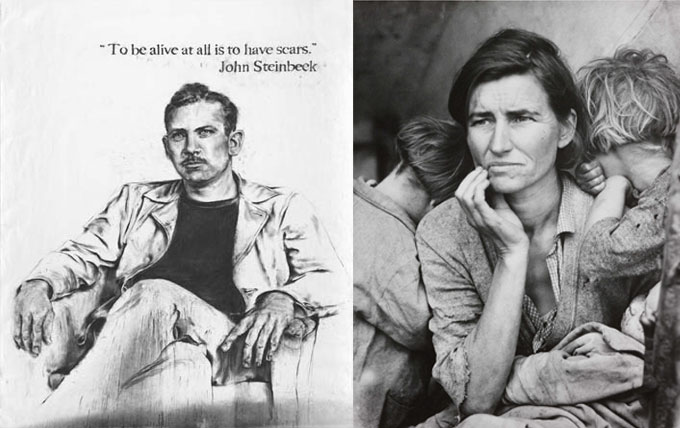

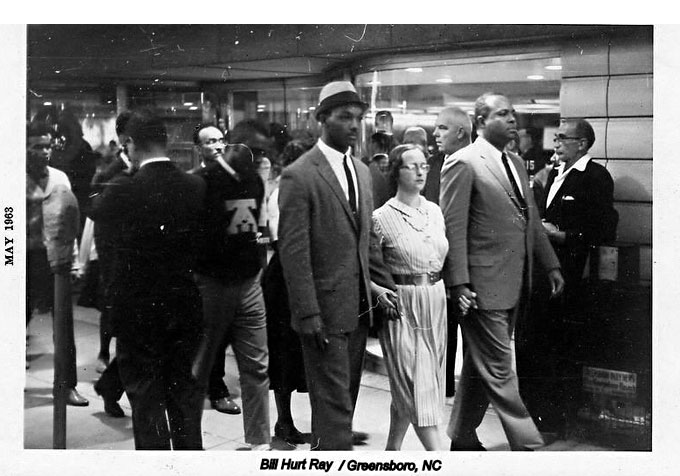

Yale University has launched Photogrammar, a handy interactive website that pairs images of the Great Depression from the Library of Congress photo archive with the photographers who took them and the places where they were taken. Like The Grapes of Wrath, the photographs of Dorothea Lange and others were intended to educate, engage, and convince average Americans that the poor were human, too. Commissioned by the U.S. Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information and assembled between 1935 and 1945, the 170,000-piece photo archive—like the California migrant camp celebrated by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath—provides eloquent testimony of government’s power to do good, despite naysayers from the right, when disasters occur. The ambitious Yale University project was funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a 40-year old federal agency that will disappear if Donald Trump’s proposal to defund the arts and humanities—along with safety-net social programs like Meals on Wheels—is approved by Congress.