REsolve Studios, a visual-artist group in Marietta, Ohio, is designed with both visual artist and local community values in mind. Its distinctive connection to literary artists, including John Steinbeck, involves sharing shows that travel to other venues in the Southern Ohio-West Virginia area. The Appalachian Soul, a show that featured a distinctive installation called “The Victorian Brain,” is one example of exhibitions that make local and literary references of special significance to lovers of John Steinbeck, interactive art, and the Appalachian heritage. Ideas and images from The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men informed the exhibition’s eclectic visual elements, reminding viewers that John Steinbeck’s circle of friends at the time he wrote these books embraced visual artists, musicians, and other writers. In the following text by a Chillicothe, Ohio poet-editor and SteinbeckNow.com contributor, visual-artist interviews and individual artist statements suggest how John Steinbeck’s social vision applies to a region suffering marginalization, deprivation, and conflict similar to the cultures of the Dust Bowl, California, and Mexico depicted by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, The Forgotten Village, and The Pearl. The writer remained painfully aware that genocide was the price of expansion under the invading Spanish, and the rapacious Yankees who followed. The earliest settlers of John Steinbeck’s California were the Ohlone Indians. Chillicothe, Ohio, the home of ancient Indian cultures predating the Ice Age, was later settled by the Shawnee people for whom the city is named. To the east of Chillocothe, the historic town of Marietta, Ohio sits on the West Virginia border. A station along the Underground Railroad before the Civil War, it is the site of the Marietta Earthworks, a burial venue of the pre-European Hopewell Indian culture referred to in the introduction to Kathleen Burgess’s interview with the visual-artist group eager to talk about their sense of mission and heritage, and their appreciation of John Steinbeck.—Ed.

Driving through the Marietta, Ohio neighborhood occupied by the REsolve Studios visual artist collective, I found one of Geoff Schenkel’s murals transforming the wall of an old brick building. On one side of the two-story studio, a garden blooms on land the artists reclaimed from an abandoned gas station. I first met core members—Geoff, Michelle Waters, Lisa Haney-Bammerlin, and Todd Morrow—in 2014 when they were installing The Appalachian Soul at PVG Artisans, a gallery in Chillicothe, Ohio, where I live. Gallery owner Cynthia Davis saw, in REsolve Studios’ blend of energy and social purpose, artists on a spiritual quest to redefine being an artist in Appalachia. They reimagined and reconstructed the exhibit for her gallery. Geoff and Michelle wrote the artists’ statement for the show:

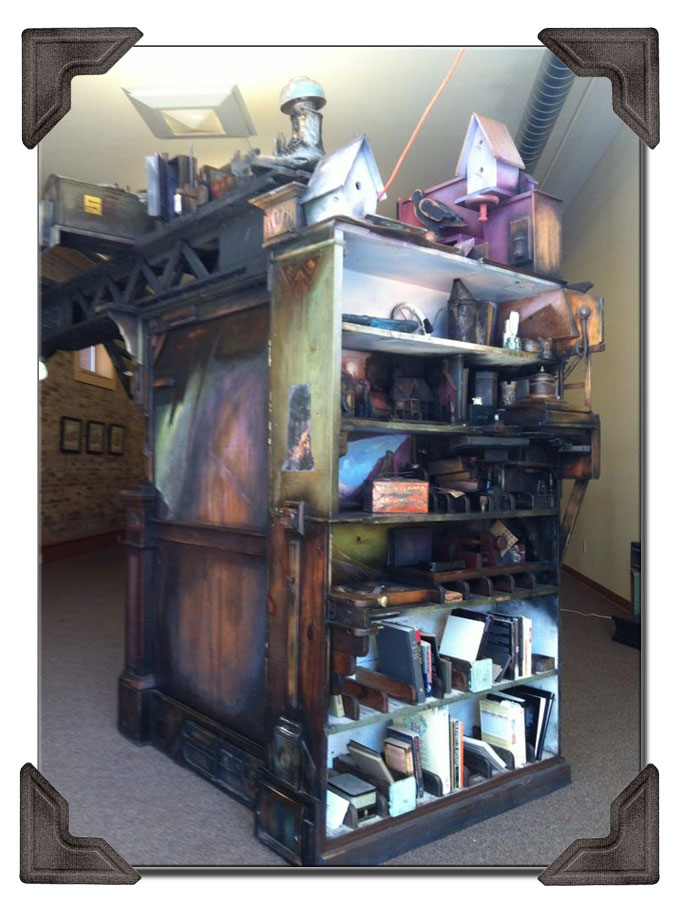

It is a massive, yet intimately approachable, room-sized sculptural environment. Anchoring this innovative combination of literary, musical, and uniquely mixed visual sources, this exhibit draws viewers to its wildly sprawling interactive core and continues to reward its “participants” when they pull back . . . to catch their breath while taking in the surrounding, focused satellite works. This deeply engaging, richly cohesive yet hard-to-define body of work represents the adventurous, even noble inclinations of REsolve artists to reach for a better life by letting go of the comforts, conventions, and security of their known world and seeking new depths in a wilderness of worlds yet to be defined.

Geoff and Michelle stayed in Chillicothe for days assessing the community’s character and needs. Several of the artists presented workshops, spending hours commuting from their homes in the river cities of Marietta, Ohio and Parkersburg, West Virginia. They also attended literary, art, and music activities at the gallery and were embraced by the Chillicothe, Ohio arts community.

“The Victorian Brain” occupied the center of the gallery, an eight-foot-high block of cabinetry with shelves, drawers, and cubbyholes exposed on all four sides. Its small doors, audio features, moving parts, books and notebooks, and written messages invited interaction. Sturdy beams connected “The Brain,” as it is affectionately known, to other sections, creating a 10’ x 17’ foot space large enough for several visitors to enter and move through at the same time. An outer layer of photographs and sculptures on walls, shelves, and pedestals surrounded the central structure. Some participants sought to contribute and added small objects to the installation. Others moved elements to different places as they passed through. Children contributed notes taped to shiny stones. A beekeeper added an antique bee smoker.

The theme of Appalachians coping with economic, societal, and environmental pressures, limited opportunity, and traditional values fits the city of Chillicothe, Ohio, the first and third capital in the history of the state. White settlers arrived in the 1700s when President Thomas Jefferson granted land to members of the victorious Continental Army following the Revolutionary War. People of the region are proud of this heritage, yet are sometimes seen by outsiders as unlettered and incompetent, as expendable as the Indians driven from Ohio 200 years ago. Authors Allan W. Eckert, Ron Rash, Donald Ray Pollock, Roy Bentley, and Diane Gilliam, among others, have written about Appalachian culture from this perspective. Despite challenges, however, Chillicothe, Ohio continues to plan for the future with optimism, and the area is under consideration for designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of the stunning Hopewell earthworks being rediscovered and authenticated by archaeologists using lidar technology.

Visual Artist Interview: John Steinbeck in Appalachia

Kathleen Burgess: Welcome to the Steinbeck Now community. Please tell us about yourselves and how literature, and John Steinbeck in particular, figures in the life and work of REsolve Studios.

Geoff Schenkel: We come from humble beginnings. We have challenges. We struggle. We feel uncertainty. When we are together, I feel at times like George and Lennie from Of Mice and Men, almost as if they are different parts at work in my mind, dreaming of something better than when we are on our own. Fellowship is great, belonging is great, but it feels fuller and richer when it is infused with purpose. Of Mice and Men normally travels with the exhibit, and it reflects some of our work as a team of artists.

At PVG Artisans we organized groupings of art into seven interrelated clusters. Each part drew inspiration from a written work. Books are featured because of a question posed by Kentucky-born Gurney Norman (Kinfolks) many years ago at an Appalachian conference that addressed issues of marginalization and stereotypes. He asked, “What would essential reading for the Appalachian region include?” Answering Norman’s question guided the creation of “The Brain.” Michelle and I, as content curators, selected seven works from a list that is now quite long. Around this core we organized The Appalachian Soul. Our raw library responds to Norman’s question with answers derived from many cultures, including John Steinbeck’s California-based work. For me, REsolve’s work expresses, from the margins of mainstream society, a perspective shared in Steinbeck’s writing.

KB: What is REsolve Studios? How does the name describe what you do, who you are together?

Anthony Wilson: The REsolve name is about solving things by thinking through solutions from all possible angles via collaboration. It’s about working together and building a better community, reconciling our own pitfalls, and making ourselves better people. We improve ourselves, and, thereby, our immediate environment, which extends to the overall community.

Lisa Haney-Bammerlin: For me it means family, a sense of belonging. It means giving a new sense of purpose to discarded things. It’s the will to keep going no matter what is thrown our way. Much like the discarded items, we all were once needed but have to adapt to challenges. Having friends, brothers and sisters, makes the journey less daunting.

Todd Morrow: REsolve = the determination to bring about a solution.

GS: After several years as a community muralist, I began doing studio-based work and toyed with the idea of calling the studio “Junk Man Designs” to play off the found objects I was beginning to use in my work. REsolve worked because it has to do with committing and then living with a decision. We seem like a practical lot of dreamers who lean toward healing the broken, fixing up the discarded, loving the imperfect, and finding a home for the outcasts.

I decided to seek others of similar mindset. If I couldn’t find them in neighborhoods, towns, physical communities, maybe I could find them in communities of shared interest, similar mindset, values, wishes. Todd chose to join. Others passed through. Then Anthony found us. He said he hadn’t become the artist he wanted to be yet and wanted to discover what he was capable of in this community. We attempted big projects, leaps of faith. Michelle liked the work she saw coming from the studio and reached out to us. She said we’d have a hard time getting rid of her. I was concerned I wouldn’t be able to deal with her overwhelming cheerfulness, but it didn’t turn out that way. Lisa found in us kindred spirits. Here we are, a family of choice with all our imperfections.

KB: Tell us something about John Steinbeck that engaged you in planning and creating The Appalachian Soul.

GS: (Quoting Tom Joad’s description of Jim Casy in The Grapes of Wrath): But now I been thinkin’ what he said, an’ I can remember—all of it. Says one time he went out in the wilderness to find his own soul, an’ he foun’ he didn’t have no soul that was his’n. Says he foun’ he jus’ got a little piece of a great big soul. Says a wilderness ain’t no good, ’cause his little piece of a soul wasn’t no good ‘less it was with the rest, an’ was whole. Funny how I remember. Didn’ think I was even listenin’. But I know now a fella ain’t no good alone.

I believe what Tom Joad says. In that place I’d called alone is the breeding ground for violence and the hurt we unleash actively and passively against ourselves and others.

KB: How do you engage the neighborhood through your art and your garden?

GS: Through our art we seek to create a place where it’s safer to imagine what is possible, safer to explore differences in ways that are open, not competitive, trying to find resolutions to chronic problems, and ways to accept human imperfection. Some might call our work “mentorship.” We work with schools, community groups, and religious individuals, while thinking with others about issues of sustainability, community, inclusiveness, and fairness. Something I’ve always valued about this work is its ability to surprise. Many come to it in joyful, childlike response.

While I love that and want that to be part of the experience, I also love that below the surface there is more going on related to Appalachians coping with outsiders’ attitudes and challenges. Recently I got the great opportunity to watch a young man explore “The Brain.” He’s at that stage of life where he’s getting a sense of himself in the world at large. There is for him a dawning awareness of just how big the world and its issues and its forces can be.

As he explored, sort of posturing as he went, not wanting to be too interested, trying to maintain his cool, on-top-of-the-world football star swagger, he unrolled one of the hidden messages like a fortune from a cookie, and he read these words from a 1912 New York Times editorial titled “Education or Extermination”: The majority of mountain people are unprincipled ruffians. There are two remedies only: education or extermination. The mountaineer, like the red Indian, must learn this lesson. As he read, his jaw dropped and he impulsively showed everyone around him. That back and forth between magical, playful elements and jaw-dropping, serious understanding is our aim.

We seek to make the studio and gardens spiritually and physically a healthy, nourishing place by amending once neglected soil through intensive composting and sharing with others the abundance of what grows here: art, food, and human relationships through mutual exchange.

Michelle Waters: I think the moments that struck me the most were when I was working in the garden, people I didn’t know would drive by and smile, honk, wave, as if they supported the act, the momentum of what we were doing. That felt really special to me. I also really enjoy the concrete blocks that have become a part of the garden’s retaining walls—the blocks that we made with the local boys and girls club, creating art together that they could see when they walked through the neighborhood, and be proud because they helped make their part of the planet more beautiful.

KB: How have you grown within the collective and in interactions with communities you’ve served?

GS: Fighting the bitterness that stems from living in proximity to what some call a “sacrifice zone” isn’t as hard as it once was, and the desire to punish others for their inhumanity doesn’t burn as strongly. Doling out punishment isn’t my job, and with that burden removed I can grow into being a healthier participant in this creation we share. I’ve witnessed suicidal individuals become more forgiving of themselves and seen people at wit’s end come here to ground themselves, seeking comfort and a chance to deal with the trauma that comes from life.

KB: How do you make decisions—regular, structured meetings, or another way?

GS: We have had regular meetings. We are currently working on our own projects, but we come together every so often to reconnect. We discuss things as if we were a family sitting around the kitchen table weighing facts, opinions, options, then sorting the tasks that need to be completed to reach our group goals. It is not a clean, efficient business model. It doesn’t run itself, but this method has produced some wondrous results. I think we go by instinct, or hunches. Michelle wanted to create the exhibit at PVG Artisans. Anthony and Todd wanted to do the steampunk show in Athens [Ohio]. Those turned out well on many levels. We constantly adapt to challenges.

KB: No other studio captures the spirit of this region, its traditions, realities, and potential, better than REsolve Studios. I know that your art offers chances for exploration and delight, with serious educational implications. Thanks for sharing your thoughts about John Steinbeck, community, and art at SteinbeckNow.com.

Photo of Michelle Waters, Todd Morrow, Lisa Haney-Bammerlin, and Geoff Schenkel by Cynthia Davis.

Photo of “The Victorian Brain” courtesy REsolve Studios.

Photo of Anthony Wilson courtesy Michele Coleman.

Very well written and a wonderful composite of life, art, creativity and exploration within this region I know well, and love. Thank you all for allowing us at PVG Artisans to host such wonderful artists within our space in the Historical Downtown District of Chillicothe, Ohio.