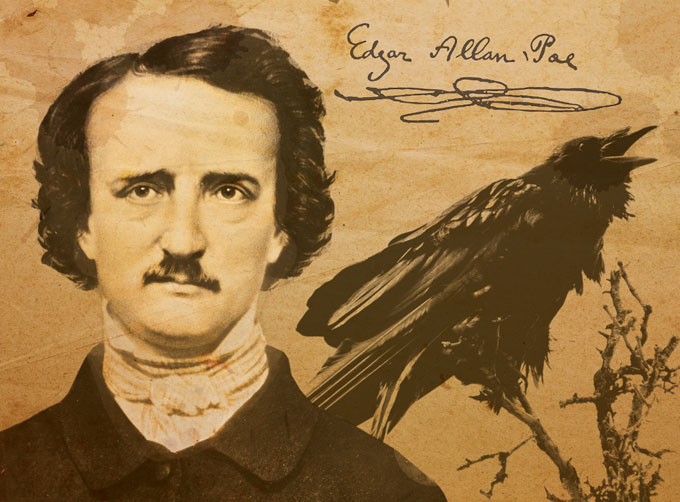

This play is drawn from stories told to me by people named Jimmy and Lily and Herb and Carole and Jean and others, all but one of them now gone and, of course, my imaginings. It wants simply to recreate the tension and dangers writers may experience when what they write draws powerful, sometimes violent opposition. The drawing by C. Kline captures part of the dark and chaotic world the play’s main character experiences for writing the truth.

I

Salinas and a Town on the California Coast

1938 and 1988

Lights up on a simple wooden table, stage right. Seated on one side, Carol typing. On the other, J.S. in his mid-thirties looking through his notes, writing with a pencil, pushing writings over to Carol, who reads then types the words. A rotary phone on table. It is 1938.

Stage left, Lily, pushing ninety but strong, great mane of gray-white hair, at a desk. A phone on the desk.1988.

Lighting changes in this scene as needed to denote changes in time, from past to further past; interchanges, actual or remembered; on phones or not; etc.

Upstage, distant, the abstract image of an oak tree. Perhaps sculptural. Just barely made out but looming in a late-morning mist or fog.

Lily (Writing in a note tablet): It was ‘37 or ‘38, something like that . . . anyway, half a century ago . . . what’s this? ‘88? . . . all flies by . . . feel I need to set this down while I can. . . (To audience, smiling) Getting old . . . . (Back to writing) John wrote about us, so I feel free to write about him . . . .

Continues writing.

Carol (Reading notes, while typing, after a silence): . . . these notes are good . . . .

J.S. (Unsure): Are they?

Carol: . . . almost like you’re writing the chapter now, instead of later.

J.S.: Believable?

Carol: Sure . . . I like he’s saying . . . you know, about when a cop . . . .

J.S.: Not too much?

Carol (Smiles): Well, won’t win you friends in some quarters . . . .

J.S.: No . . . .

He goes back to notes. She looks at him. They continue working. She looks up again, watches him, then resumes typing.

Lily (Writing): . . . It begins with . . . bunch of us, Salinas High class of 1919 . . . deciding on a reunion . . . sudden . . . spontaneous . . . nothing formal – just talk, spouses, kids . . . catch up on each other’s lives . . . . My Len’s idea over some beers . . . . (Looks up, says to herself wistfully) Len’s gone a long time now . . . .

Carol (Stops typing, concerned, pause): You okay?

J.S. (Smiles thinly): Yeah . . . .

Carol: You’re quiet . . . .

J.S.: We’re working.

Lily (Writing): The others, they asked me to call John, invite him to our reunion. You can talk anyone into anything, Lily . . . that’s what they said . . . truth be told, I was pretty good at it . . . back then.

Carol (Pause): Lots of calls today . . . .

J.S.: New York?

Carol (Nodding): I told them we’re progressing . . . that you’re still researching . . . still going into the fields . . . maybe we can meet their deadline . . . .

J.S. (Doubtfully): Hope they’re patient if we can’t . . . .

Carol (Strong): It doesn’t matter – you can’t rush it. Too important. They’ll wait. (Pause, little tense) One of the calls. . . this woman . . . said she was a classmate . . . high school . . . .

J.S. (Looks up from his notes, interested): High school?

Carol (Watching him): She gave the name Lily.

J.S.: Lily? (Quickly, smiles) Oh, right – Lil’! Good old Lil’!

Lily (Suddenly stops writing, looks at audience): I could tell on the phone she was suspicious of me. If she’d seen how homely I was . . . mind you, this was fifty years ago . . . . wasn’t as homely as I am now . . . .

Carol: Deep voice.

J.S.: That’s Lil’. We all thought she should be on the radio – could have been a disc jockey maybe.

Lily (To audience): Some people thought my voice was sexy.

Lighting change.

Carol (Picks up phone, into phone): And you want . . .?

Lily (Also): We’re planning a get-together – cold beers . . . talk about the old days . . . hoping John will join us . . . he was president of our senior class after all . . . .

Carol (Curtly): Yes, I know all about that.

Lily (Picking up on it, a beat): Of course, we’d love to have you, too . . . the park with the big live oak tree – John will know . . . .

Carol (Tersely): I can’t make commitments for him. Call back this evening, please, or better, leave a number and if John has the time . . . he’s on deadline . . . . your name again?

Lily (A beat): Lily.

Lighting change.

J.S.: What did Lil’ want?

Carol: A reunion. High school classmates. Informal. She said someone’s idea . . . Len’s?

J.S.: Her husband.

Carol: Over some beers.

J.S. (Laughs): As much Lil’s idea then – she likes her beer.

Lily (To audience, picking up receiver): He called back . . . imagine me fifty years younger. . . voice not so gravelly then.

Lighting change.

J.S. (Into phone as Carol types, while listening): Lil’, so glad to hear from you. What a surprise!

Lily (To audience, covering receiver with her hand): That’s what he called me in high school – Lil’.

J.S.: How’s Len?

Lily (Into phone, in the 1930s, sounding younger): Len’s fine, John. Did you hear? We’ve opened a shop downtown, just off Main.

J.S.: I heard – antique clothing and old furniture – what a combination!

Lily: Tell the truth, lot of junk. Barn stuff – old harnesses and the like. Sad, you know?

J.S. (Pause): Yeah.

Lily: Small farmers losing their places – not the big growers, of course. (A beat) Now and then a nice old rocker or settee still has some velvet upholstery comes in. Don’t know why, but makes me want to cry.

J.S.: Broken dreams, Lil’.

Carol, who has been trying to eavesdrop, pulls the piece of paper from the typewriter, can’t find another sheet, leaves.

J.S. (Watches her go, waits a moment, a touch slyly, sotto voce): Say, Lil’, do you have any old cowboy hats in that store of yours? I might be in the market . . . .

Lily (To audience): He was into cowboy stuff for a while. Word is he bought a pair of new boots in San Jose – shined them and proud as a kid. (Into phone, younger again) No old cowboy hats now, but I’ll keep an eye . . . . Sometimes we get a nice old Stetson from a broke cowboy. Heaven knows there are enough broke cowboys about.

J.S.: I’ve seen them, Lil’ . . . up and down the valley . . . a few taking work in the fields . . . .

Lily: Pretty sad, you ask me – can’t get sadder than bow-legged cowboys bending over harvesting vegetables . . . .

J.S.: Keep the hat thing between us, okay?

Lily (Hesitates): John, you gonna’ write a book about broken down and broke cowboys?

J.S. (Laughs): I have enough on my hands with mistreated fieldworkers, Lil’.

Lily: Just wondering . . . . We do have a nice blue rhinestone shirt with pearl snap buttons. Cowboy about your size. Thrown bull riding – broke his arm and bruised his tailbone. Doesn’t think he’ll be wearing that shirt anywhere nice for a while. And can sure use the jack.

J.S.: Can’t see myself in rhinestones, Lil’.

Carol returns with more typewriter paper, sits, inserts piece of paper and resumes working and listening in.

Lily: Didn’t think you could . . . . (Hesitates) John, Len and some others of us from the class . . . .

J.S. (Quickly): Carol told me, Lil’. . . about your reunion. (Glances at Carol) Sorry, I can’t . . . .

Lily (Into phone): ‘Cause we know you think there are people out to do you harm – growers and the law and all.

J.S.: Lil’, really, just can’t.

Lily: People you imagine want to do you harm . . . .

J.S.: Lil’, no . . . . Say, I heard you have a new baby girl . . . does she favor you or Len?

Lily (To audience): Well, it was a baby boy, not a baby girl, and he favored Len – and I wasn’t about to give up on our reunion in the park. (Pause, reflectively) You do dumb things when you’re young . . . just plow ahead like everything will work out no matter what, never considering for a second all the bad things can happen. So, kept at him and kept at him until, finally . . . .

J.S. (Resigned): Okay, Lil’, for you and Len I’ll do it . . . just this one time.

Lily (Into phone): That’s wonderful, John. By the big live oak, twelve or so, a picnic lunch. You remember that big oak, don’t you?

J.S. (Pause): Sure, Lil’, I remember it . . . old when we were kids. Probably saw the first Spaniards on their way up from Mexico.

Lighting change.

Lily (Replacing receiver, picks up pen, begins writing again, old): I wish to God he’d stuck to his guns . . . but I persisted . . . and he did come . . . . (Pause) You can’t take any of it back once it happens . . . funny how we always seem to forget that.

J.S. (Sets phone down, guiltily to Carol who is staring at him): Felt I couldn’t disappoint them, especially Lil’ and Len . . . . (Pause, cautiously) Want to come? . . .

Carol (Strong): Why would I want to come? I don’t know them.

J.S. (Mollifying): They’d like to meet you . . . .

Carol (Sharply): They don’t want to meet me.

J.S. . . . see their husbands and wives and kids.

Carol: Don’t lie to me, John.

J.S.: Lil’s kids . . . .

Carol (A deep resentment): Oh? You think I’d enjoy that – seeing another woman’s kids?

J.S.: Not that again . . . (Gestures vaguely, an old wound) . . . not while we’re working . . . .

Carol (Pause, studies him): So, you’re really going.

J.S.: Said I would . . . .

Carol: Go ahead then. Don’t get drunk.

J.S.: Right . . . .

He pushes his notebook to the side, looks off. She studies him for a few moments, softens.

Carol: Sorry . . . I’m sorry, John. Wrong time to bring it up . . . you’re right, no place for arguing when we’re working . . . publisher waiting. (Trying to loosen him up, smiling) We can always fight later, right? . . . (Pause, worried): John . . .?

J.S. (Holding her at a distance): Yeah?

Carol: Fight later? Work now?

J.S. (A beat): Sure . . . .

Carol: Good. (Pause) Did something happen in the fields today? When you get quiet like this . . . .

J.S (Considers, shrugs, looking away for a moment): Not much . . . the usual . . . . (Tries to smile, softening) But I’m sure glad Prohibition’s over . . . .

Carol (Smiles): Me, too . . . when we’ve finished with these notes . . . couple drinks . . . maybe something else . . . to make up . . . but we have to finish first . . . .

J.S (Smiles, looking away): No let-up.

Carol: None while it’s fresh . . . .

J.S. (Pause, conceding her importance): I know that without you pushing me . . . .

Carol: Oh, you’d do fine.

J.S.: I don’t know . . . .

Carol: Thanks anyway.

He nods, turns to his notes. Carol watches him for a few moments, resumes typing, slowly, from notes.

Lily (To audience): We learned later – it’d been a dark day for him, the day I called. Surprised he came to our reunion when we heard . . . took courage . . . guess he didn’t want anyone thinking they could scare him off from his hometown – like they did before, according to some.

J.S. (Can’t concentrate, looks up, hesitates): You really want to hear?

Carol: What?

J.S.: What happened today.

Carol (Bracing herself): Sure . . . guess I’d better.

J.S. (Becoming shaky as he tells her): I’d just pulled over . . . gotten out . . . . Workers harvesting lettuce . . . near the river . . . wanted to talk to a few of them, that’s all . . . the usual, you know . . . then a truck roars up, sprays gravel . . . three guys jump out. And for the first time – one pulls a gun . . . says I write another word about . . . you know . . . and the fieldworkers hearing it all. (His hand shaking, he sets pencil down) . . . . One yells what was about to happen to me could happen to the fieldworkers . . . if they didn’t keep in line . . . shooting me and throwing my body in the river . . . said would suit me fine since I write about the river and death so much . . . .

Lily (Writing): ‘Course we didn’t know there was real danger or we wouldn’t have asked him to the picnic . . . thought he was imagining most of it . . . thought it was safe . . . really did . . . a public park, families and all . . . center of town . . . what’s the harm in that?

J.S.: . . . maybe if I’d had a gun . . . .

Carol (Shaken): No – they’d just use that for an excuse to . . . .

J.S.: Followed me a few miles in the truck then turned back – U-turn, squealing tires . . . no doubt back to terrorizing the workers.

Lily (Writing): . . . we’d thought he was imagining the hostility . . . . (Pause, looks around her surroundings, to audience) This store buys old stuff from the public for resale . . . someone comes in with old books, often one of his, the nightmares begin again for me . . . had them all these years from that day by the old live oak . . . .

Carol: You tell the police?

J.S. (Softly): Hell no!

Carol: John!

J.S.: . . . they work for the growers . . . .

Carol: You need it on record – what happened.

J.S.: They’d laugh.

Carol: Pulling a gun on someone is an indictable offense!

J.S.: If you have a witness.

Carol: The people in the fields!

J.S.: Do you know what they’d do to them? Do you? These people have families . . . I couldn’t ask . . . .

Carol (Pause, conceding): We can’t just wait . . . .

J.S.: A gun.

Carol: They’d say you threatened them with it – you think they wouldn’t go to the police? Way to legally put you away, shut you up. Or kill you and claim self-defense. Besides, they wouldn’t come here.

J.S.: So, I can’t return to my home? Can’t meet Lil’ and high school friends by that old oak tree?

Carol: You’d still do that? After what you told me happened today?

J.S.: They’re not stopping me again. Had to sneak into my own home . . . hidden in the back seat of a car . . . when mother was dying, then father . . . .

He looks away, has trouble picking up the pencil, bends over his notes. She watches him, exasperated. Lights dim on them as they work quietly. He writes, pushes paper to her; she types, slowly now, both going through the motions.

Lily (Writing): Other day I visited the park where we held our reunion that Sunday . . . that old oak still there . . . will be when we’re all gone and forgotten . . . not him, they’ll remember him alright . . . .

Lighting stronger on the oak, sounds of people talking, children playing. She looks toward the tree and a now-gathering mist.

(To herself) One of those foggy summer days we get in the valley. Clings to the ground . . . good for the growers . . . holds off drought. (Pause) Don’t know how many times I wished he’d not come, but I wouldn’t accept his refusal . . . had to keep after him . . . .

Pause. Tries to smile.

(To audience) He was happy for a while that Sunday – about his next book . . . seeing friends, telling and hearing stories . . . a few beers . . . think he believed me – if Lil’ promises it will be safe . . . then . . . .

Pauses, shakes her head.

Then it happens – truck jumps the curb onto the park grass. Comes right at us, through the mist, wheels spinning, skidding sideways, no concern for people socializing on a Sunday afternoon – could have killed a child . . . when I think that a child could have . . . .

Looks toward the live oak tree. The roar of a truck engine from upstage, distant, echo-like.

An old pickup truck – one of those with big headlights they had back in the ‘30s . . . mounted on top of the fenders the way they did back then – like cartoon eyes. I’ll never forget that truck coming at us with its cartoon eyes. It seemed like a living thing. We save our kids – gather them in!

They throw him against the big live oak tree . . . shove a gun under his chin . . . hit him in the stomach . . . in the stomach so it doesn’t leave a mark, so the law can’t see he’s been roughed up . . . that’s what Len told me . . . that’s how they do it.

Pause.

Then they laugh . . . drive off. We pull our children close . . . want to call the police . . . he pleads no . . . swears us to secrecy . . . we keep that secret . . . all these years . . . most of us dead now . . . even those years when writers came ‘round wanting to know about him . . . asking questions . . . none of us speaking a word . . . because we promised. I didn’t like it even then, keeping it hidden . . . that’s why I’m writing this – he’s gone now, people should know.

Lights back up on John and Carol, working.

So, guess what he does – very next day . . . drives all the way back to Salinas . . . in the morning . . . to the county courthouse . . . . Applies for a license to carry . . . on his person . . . .

Lighting beginning to fade on Lily, then up on J.S., studying his notes, trying to concentrate; Carol, looking at him, concerned, while typing.

Carol: John . . . .

He doesn’t look up.

Carol: Please?

Lily’s Voice (light on her dimming to darkness): . . . to carry on his person, for self-protection . . . well, you know . . . a gun . . . arming himself . . . .

J.S. looks up, smiles faintly; Carol smiles back – a kind of truce they have grown into.

Carol: It’s good.

J.S.: Is it?

Carol: Believe me – yes. I start reading, I forget I should be typing.

J.S.: Thank you . . . .

He bends back over his writing.

Carol (Pause): You’ll be careful Sunday?

J.S. (Looking up): I’ll be careful.

Carol: Promise?

J.S. (Pause): Yes.

Carol: You won’t take a gun?

J.S. (Turning back to his notes, a beat): I won’t.

She watches him, unsure, then she begins to type again.

The sound of the typewriter continues for a few moments, the stage going dark except for the live oak. Only the tree in the mist visible, then the lighting on it fades to darkness as the sound of the typing dies away.

II

Salinas

Mid-1940s

Seven or eight years later.

Abstracted: The interior of a period service station. Suggestion of gas pumps can be partially made out through a glass door under exterior lights in the evening darkness. A pot belly stove, the fire extinguished, a large old cash register on a stand. A chair pulled up to the stove, a book with a page marker and a lunch box on the flat arms of the chair. A radio tuned to country and western music.

Henry, wearing a station attendant’s uniform, is counting money from the cash register, putting cash in a pouch, zips it closed – hesitates – looks toward door, picks up closed sign and goes to door, opens it, hangs closed sign so it is facing out, shuts the door.

He hears a car pull in, shakes his head, mutters to himself, grabs a broom and begins to tidy the space.

A middle-aged man comes to the door. He is black, neatly dressed, strongly built. He tries the door. Henry turns. If he is surprised, he doesn’t show it. He says and mouths, “We’re closed.” The man indicates he can’t hear Henry. Henry turns off the radio, leans the broom against the wall, closes the cash register drawer and goes to the door, hesitates just a moment, then unlocks and opens it.

Henry (With authority): I said, we’re closed.

James (Evenly): Don’t need gasoline, sir.

Henry: Well, sorry, can’t help you anyway – Bob our mechanic’s gone home.

James: Don’t need repairs, sir. But I do have someone in my car wants to talk with you.

Henry (Looking past James, shaking his head, amused): That old gas guzzler?

James (Smiles): Sure does – we’ll need to fill er’ up with ethyl before we go.

Henry: Not here at this hour. I don’t need business that bad – I’m ready to go home.

James: The gentleman sure would like to see you this evening, sir. A matter of pressing time.

Henry: Hiding in the gas guzzler then?

James: You come out and see him, maybe he’ll tell you why. (Smiles) You never know – he might have a real good reason.

Henry becomes curious, steps back, opening the door and allowing James to come in.

Henry: Maybe you’ll tell me instead.

James (Steps in): Rather he did, sir.

Henry: Then he can darn well come to the door, as you have.

James (Smiling): I was told you might say something like that and I understand, but please consider making an exception this time.

Henry looks at him.

Henry: So this person doesn’t want to be seen?

James (Nodding): He doesn’t, and I’m afraid he may already have . . . . (Trails off)

Henry: Been seen?

James: (Nodding): . . . Wanting to visit with you, he took a chance and came anyway.

Henry: Not good if he’s seen?

James: Not good.

Henry: I know this person, then?

James: Very well, sir.

Henry (Smiles): It must be . . . it’s John, isn’t it?

James (Smiles): Yes, sir.

Henry: I’d heard he was back . . . in Monterey, not here. . . didn’t think he’d show himself in Salinas.

James: Tell the truth, I tried to talk him out of it. Wouldn’t listen to me wanted to see you so bad . . . so we’re here, causing tension . . . .

Henry: That’s John. Tell him to slip in, no one will see him. And if they do, so what? – he knows I won’t stand for any trouble.

James: I can’t see him slipping in anywhere – he’s big as me.

Henry: Well, I’m not going to sit in a high-octane gas guzzler, so tell John it’s up to him.

James: I’ll see what I can do. (Starts for door, stops, turns, can’t keep from smiling) He said you’d have an argument for everything – I’d never heard a car being a gas guzzler used as an argument not to see someone. Or refuse to put gas in it. He sure caught you alright.

Henry (Quietly pleased): Me? John did?

James: So far, yes.

Henry: Don’t start thinking you can predict me.

James: He told me that, too.

Henry: We go way back . . . and you’re? . . .

James: James – my name is James Neale. You’re Henry and I know all about you. Heard a lot of stories.

Henry: Did he tell you I bossed him when we were kids?

James: I don’t recall him saying anything about that.

Henry: Wouldn’t think he would. I bossed him, even though I was smaller and younger. Then I caught up and we became equal. Were last time I saw him, lot of years ago, even though he was becoming known some. Don’t suppose he’s changed?

James: Well, I wouldn’t know about that, only knowing him a few years off and on. Changed only a little in that time. (Moving toward door, stops, turns, smiles) If you won’t take offense, I do recall him saying you are a hardheaded man.

Henry: No argument there.

James: Yep, there we go – he said you wouldn’t argue that either. (Suddenly serious, gesturing to the outside, his voice softening) You mind, Henry, putting out those lights over your pumps? Would help, I think. You know what I’m saying.

Henry (Pauses, then looks): Suppose it would.

James: Never know – might encourage him to come in.

Henry goes to switch, flips it, outside becomes almost total darkness.

James: Better . . . thank you, sir.

James leaves. Henry looks around, tidies just a bit. J.S. enters quietly, self-consciously, James opening the door for him.

James (Slipping back into the darkness): I’ll be just outside, keeping an eye. If you need me . . . .

J.S.: Thank you, Jim.

J.S. is nervous, ill at ease, keeps his distance at first. Looks around. Henry stands by cash register, also a touch self-conscious.

J.S. (Clears his throat): It’s a fine station, Henry. Four pumps! I knew you’d get it – you said it was what you wanted when you were twelve.

Henry (A touch challenging): I was eleven, you were the one was twelve, John.

J.S. (A beat): Well, you got it anyway.

Henry: So? Maybe I wouldn’t have if my father hadn’t died. Who knows what I would have done . . . that changed everything . . . when I dropped out of school weren’t many jobs for anything, then recalled I’d once wanted to do this . . . that I’d told you and Mary about it when we were kids . . . . So if he hadn’t died, maybe I’d have stayed in school and been something else, a lawyer or banker, something like that.

J.S.: Maybe.

Henry: I think I might have made a good lawyer.

J.S.: I never won an argument with you.

Henry: I don’t think you knew what you wanted to do yet . . . when you were twelve, I mean . . . . Did you? I don’t recall you saying . . . all those times we sat on the river bank talking with Mary, swimming and catching lizards.

J.S.: I don’t think I really knew when I was twelve.

Henry (A beat, definitely curious): You know when you did?

J.S.: Only hints, nothing sure.

Henry (Disappointed): Just wondered. Guess it doesn’t matter.

J.S.: Guess it doesn’t.

Henry: You read a lot, though.

J.S.: Sure.

Henry: You’ve done well for yourself.

J.S.: Thank you.

Henry: And you didn’t finish school either.

J.S.: Not even close.

Henry: We’re a couple dropouts.

J.S.: Not so bad. Some of my best friends . . . .

They are both quiet for a moment.

J.S. (Breaking the silence): Glad you got to meet Jim. Studying to be a pilot, in Monterey. One of those little single props – a Cessna. Took a while to find an instructor. First two guys refused to give him flying lessons – you can guess, same tired old stuff ignorant people say about Negroes. At least they didn’t say it to Jim – they’d be damn sorry if they did. A third guy, though; he was happy to give it a whirl . . . no matter what the others said. He won’t be disappointed. Jim’s had some lessons already, going to be fine. Wouldn’t surprise me if he turns out to be an ace.

Henry (Pause, a touch of wonder): You have your own plane?

J.S.: Just renting it for now.

Henry: You might buy one?

J.S.: Might.

Henry (A beat): Use a lot of fuel?

J.S. (Nodding): High grade.

Henry: He’ll fly you?

J.S.: Sure . . . safer in the air than on the ground . . . especially around here.

Henry: Like right now?

J.S.: Jim tell you something?

Henry: Hinted . . . .

J.S.: Not as bad as he might make it sound – Jim’s a careful guy.

Henry: Your bodyguard?

J.S.: I wouldn’t ask that of him. Works for me – a good friend. We look after each other. . . when I come back . . . . (Notices the medal food container) You bring your lunch to work with you, Henry?

Henry (Nodding): Saves money. Don’t take a lunch hour anyway. My mechanic Bob does. I usually pull up to the pot belly with Lorna’s soup and a good detective novel and hope no one pulls in. ‘Course, they always do, usually just when I get to a good part.

J.S. Looks at book, tentatively): What are you reading?

Henry: A mystery. By Raymond Chandler. (With an edge in his voice) That okay?

J.S.: Sure – helluva writer. (A beat) Are you happy, Henry?

Henry (A little stiffly): With the station, you mean? Serves its purpose . . . keeps my life structured . . . would do that if only had two pumps. There are other things.

Henry spots dirt on the floor, gets broom, dustpan, and begins sweeping, J.S. moving out of his way.

Henry: Do you mind? Since I’m here.

J.S.: ‘Course not. Reminds me when we were kids. When my mom caught us messing up.

Henry: Only person I was ever genuinely afraid of – your mom. Couldn’t get away with anything your mom watching. (Beat) Saves time in the morning . . . . Lorna says I should get some help for cleaning . . . but why, when I can do it myself? . . . (Stops sweeping) Are you happy?

J.S. (Shrugs): Sometimes . . . .

Henry (Emptying dustpan into wastebasket, placing broom again wall): What with all that attention you get . . . .

J.S. Doesn’t mean anything.

Henry (Veiled): Some you don’t want, of course . . . .

J.S.: Most.

Henry: Should you be here?

J.S.: I didn’t want to come and go without seeing you. I couldn’t do that. I knew you’d know . . . the way word gets around here. . . but I don’t want to cause you any trouble, Henry . . . if it’s a problem for you, Jim and I are out of here.

Henry laughs.

J.S. (Self-consciously): What?

Henry: You sounded like that character of yours . . . that big guy down by our river – forget his name – you know, “I’ll just go away, George” . . . (A bit embarrassed for quoting it) . . . or something like that.

J.S.: I sound like him? (Has to smile) Yeah, I suppose I did. Do you think I’m becoming my characters, Henry?

Henry: Makes sense you might.

J.S.: So, to paraphrase the big guy, if you do want us to leave . . . ‘cause I respect you have a business to look after . . . .

Henry: No one tells me how to live, you know that. Anybody doesn’t like the people I see – doesn’t like me seeing you – well, it’s none of their business and they can go to hell . . . .

J.S. (Pause): Some of those people can be dangerous, Henry.

Henry: You think so?

J.S.: Someday I’ll tell you stories . . . .

Henry (Dismissing the idea): Where you living in Monterey?

J.S.: You know that Mexican adobe on Pierce Street, big cypress in front . . . just above town . . . the one I used to say I wanted to live in someday? Well, I bought it. (Pause) Bad idea . . . . Something dark happened in that house, Henry. Gwyn feels it too. A murder or suicide. Maybe an infant dying – Gwyn has that feeling – but maybe that’s because we have our own baby now . . . . So even if we stay, we’ll have to get out of that house.

Henry (Skeptical): Haunted?

J.S.: Ghosts don’t bother me, evil does. Evil things happening. Remember we talked about ghosts all the time when we were kids – you were sure they were out there. Hell, I have a couple! Do you?

Henry (Thinks about it): Just my father, I guess . . . can’t seem to shake him, leaving us so soon . . . see him out there by the pumps sometimes, looking in at me as I close up for the night . . . still a young man – younger than me now . . . maybe wondering why I’m not doing something else.

J.S.: But maybe happy for you.

Henry: I guess. Didn’t get enough time with him to really know how he thinks. (Pause) You said you didn’t want to go without seeing me . . . you must be leaving.

J.S.: There’s more hostility than I anticipated.

Henry: You think you might be imagining it?

J.S. (Smiles ruefully): That’s what most people think, isn’t it? I’m neurotic . . . paranoid . . . .

Henry (Laughs): Sure, some do.

J.S. (Has to smile): Do you?

Henry: Different, we grew up together – I know you have a lot to be neurotic and paranoid about.

They both laugh.

J.S.: For sure . . . a ton . . . so, you think I exaggerate?

Henry: Some – human nature . . . especially being a writer and all . . . to be expected . . . you did it when we were kids – multiplied everything by five – hell, sometimes ten. (Grins) Challenged my math, I never knew what to believe.

J.S. smiles, then, tense, goes to the door, speaks as he looks out.

J.S.: I was that bad, was I?

Henry: Not so bad – you were a kid. Mary and Alice did the same, just not so much.

J.S. (Pause, splitting his attention between Henry and looking outside): Maybe I do stretch it a little . . . I’m not denying it . . . . But I’ll tell you something, Henry – the threats, that stuff, not as bad as . . . doesn’t hurt as much as . . . (Turns, looks at Henry) . . . the slights from people I used to know . . . who were friendly once . . . took weeks to find someone who’d rent me office space for writing . . . down on Alvarado Street, where I spent so much time in the ‘30s. Vacancies everywhere but nobody knows me anymore . . . . “Where’s your references?” Or the space is vacant and for rent, sure, but afraid it’s promised to . . . and they’d make up some name . . . stuff like that, all bull. (Pause, looks out through glass door again) One guy I know a long time . . . we always got along fine . . . said hello, runs a tobacco shop, then out of the blue says, “Big deal if you win some hotshot award for your writing.” I didn’t bring up any award – I don’t care. Where in the hell does that come from . . .?

He turns away from door.

Henry: Jealous, that’s all. Maybe he thinks you do think it’s a big deal.

J.S.: Well, I don’t.

Henry (Shrugs): Some people don’t know that.

The door opens slowly, James stepping halfway in.

James: John, we should be moving on – the car’s obvious, even in the dark.

J.S.: Soon, Jim . . . . (Nervously pulling a pack of cigarettes from his jacket) Haven’t seen Henry for . . . for a long time . . . .

James: I understand. But we want to be careful.

While J.S. is occupied with cigarettes, James gives Henry a look encouraging him to end the conversation; leaves, closing the door, but remains within view, his back to the door as if on guard.

J.S.: I told you – Jim’s thorough. Good man.

Henry: He’s right, you know. You’re going to attract attention – big Negro standing out there like that.

J.S.: That bother you?

Henry: You know better’n to ask me that.

James moves away from the door, out of sight.

J.S.: Jim is staying in the Pacific Grove cottage . . . looks after the place for us. Living there now.

Henry: That doesn’t bother me either, if it’s what you’re asking.

J.S.: Guess it could be taken that way . . . but wasn’t . . . sorry . . . jumpy . . . cigarette?

Henry: Don’t anymore.

J.S. (Nervous, clumsily handling cigarette pack): Remember when we smoked our first one, sitting by the river? Mary was with us. You got sick.

Henry: We all got sick when we saw that bloated cow floating down the river, blowflies everywhere.

J.S. (Smiles, making a face): Okay, you talked me out of the cigarette. (Puts cigarettes back in jacket pocket) I never thought of the river the same after that.

Henry: You loved that river.

Henry goes to cash register, checks for money again, finds none, locks register with a key on his keychain as they talk. He is suddenly brisk.

Henry: Don’t know why I lock it – station broken into once – couldn’t open the register so they took the whole damn thing! Seventy solid pounds of iron. New one cost me more than if I’d left it open with fifty bucks cash in the drawer for the taking . . . that would have been the smart thing. (A beat) Why’d you really come back, John?

J.S.: I couldn’t let them drive me out, Henry. It’s my home. What gives them the right to take it from me? My mother was a teacher, my father county treasurer . . . . I went to school and church like everybody else . . . . (Pause) Am I keeping you, Henry – do you have to get home?

Henry (A shift in mood, unsure): Maybe – Lorna worries.

James enters with a sense of urgency; closes door behind him.

James: John, I’m really feeling uneasy about this. The cops could stop and check and we sure don’t want that. (To Henry) Do cars ever pull into your place to turn around?

Henry: All the time.

James (To J.S): I’ve seen three already. One an old pickup . . . think I saw it behind us this afternoon on the highway from Monterey . . . (Looking at Henry) Probably just my imagination but looked familiar.

Henry (A beat): Gun rack in back window?

James: Too dark to see. What are you thinking?

Henry: Nothing, wouldn’t mean anything anyway – hunters probably.

J.S. stares at him.

James (A skeptical pause, then to J.S.): I’ll be waiting . . . with engine running . . . (To Henry, smiles, sending a message as he leaves) . . . guzzles gas, sir, even when idling . . . .

Henry (Waits, then picks up his car keys): Think I’ll follow you back to Monterey.

J.S.: Why would you do that?

Henry: Jim a good driver?

J.S.: The best. Why?

Henry (A beat): I might know that pickup . . . .

J.S. (A beat): Maybe I do, too. This isn’t hunting country, Henry, . . . south of here, maybe . . . down by San Lucas, maybe . . . . Anyone I know?

Picks up lunch container, tries to “herd” J.S. toward door.

Henry: That’s between him and me . . . if it’s this person, he’ll recognize my Chevy. He’ll know it’s me following you . . . don’t think he’d try anything once he realizes that . . . .

J.S.: Somebody dangerous, then.

Henry: Hard to say . . . hot-head type . . . a few beers and gets quarrelsome . . . next day ashamed and friendly as can be . . . lot of them like that around here . . . but if he sees me . . . .

J.S. (Both depressed and puzzled): Yeah, okay, someone else I used to know hates me . . . did I ever write about this person?

Henry: You probably didn’t . . . but might think you did.

J.S.: What’s that mean?

Henry goes to door with leather pouch, opening door.

Henry (Encouraging J.S. to exit): I don’t know, John . . . some people just take it personal . . . begin to think it’s them you’re writing about . . . you probably wrote about what he does, that’s all . . . his job . . . people he knows . . . or knows of . . . grows in his head, especially when he’s drinking and listening to what others might be saying . . . feels he has to make a statement of his own . . . . You write about people running service stations, I’m thinking it’s meant for me – old hardheaded Henry . . . hates gas guzzlers even though he has a service station and makes money off them . . . . Now there’s real hypocrisy for you!

J.S. (Smiles): Yeah . . . you’d take offense if I did that – wrote about you?

Henry: Sure . . . but you know what I’d do – give you hell from the get-go, just like old times.

J.S.: You would!

J.S. laughs as he opens door and exits.

Henry pauses, worried, one last look around, then turns off the interior lights, leaving the room in darkness, slips out himself.

Heard: the door being locked from the outside.

III

El Camino Real

1957

A decade later. The abstract, open representation of the front of a car, Including the outline of a windshield, facing the audience.

J.S. in the driver’s seat. He is wearing a corduroy sport coat and a shirt open at the collar. He pantomimes driving, from “steering” to “accelerating” and “braking.”

In the front passenger seat is Joan, a middle-aged film star wearing slacks and a plaid blouse with a western design. Her hair tied back with a calico scarf. Strong presence, matching his, perhaps surpassing it. He is in his mid-fifties. She is several years younger.

They smoke almost continuously, though like the driving this is pantomimed. She lights up for both of them, hands him cigarettes; they snub them out in a center “ashtray.” She uses a “lighter” to light the cigarettes.

She is curious, inquisitive, concerned for him, but has her own problems. She looks out the window, absently thinking about something else.

Early morning light. They are both smoking as lighting comes up on them. Some silence. Throughout lights will dim then come back up to indicate passage of time.

J.S. (Driving): You’re quiet. Too early for you?

Joan (Laughs lazily): Too early? You’re kidding, right? By this time – what is it, quarter after? (Looks at her wristwatch) I’d have gone through makeup . . . on the set studying lines . . . getting into character if the character has any . . . all that stuff . . . . You’re the quiet one. Thinking of Elaine back home?

J.S.: Sure . . . and the boys.

Joan: Bet they’re thinking of you, too. Nice family you have. When do we get there?

J.S.: Just passed Santa Barbara. Maybe five hours . . . depending . . . .

Joan (Inhaling, exhaling, waiting): . . . On what?

J.S.: Not sure.

Joan (Laughs): I love decisive men.

J.S. (Smiles): Okay – whether we get pulled over or not.

Joan: Are you planning on speeding?

J.S. (Seemingly tongue in cheek, snubbing out his cigarette): No, pull us over to get your autograph – highway patrol, sheriff’s deputies, small town cops, you know.

Joan: You’re kidding me.

J.S.: Nope.

Joan: You really think I’m recognizable at sixty miles an hour? On the El Camino Real?

J.S.: Sure.

Joan: Without makeup?

J.S.: You’re more recognizable without makeup.

Joan: Are you trying to tell me something?

J.S.: No.

Joan: I think you’re trying to tell me something – about getting pulled over, I mean. Something that is going on in that muddled genius head of yours. (A beat, ruefully) But you’re right about the makeup . . . they generally use it to soften my features. Others, they usually need to strengthen them . . . . Another cig?

He nods.

She puts cigarette in her mouth, lights it, hands it to him. While trying to keep his eye on the road he glances at end of cigarette, puts it in his mouth, exhales.

Joan (Pause): Why did you smile?

J.S.: What?

Joan: You looked at the end of the cigarette before you put it in your mouth – and smiled . . . . Because a woman’s lipstick is on it?

J.S. (Thinks about it): Yeah, I don’t know, I guess maybe.

Joan: I’ve lit cigarettes for Elaine – she’d understand. (A beat) I’m sure n’ hell not flirting with you, if that’s what you’re thinking. Are you thinking that?

J.S.: I’m not.

Joan: Good. We’re friends . . . you and I, especially me and Elaine – we’re almost best friends. Both Texans. Elaine ever hand you a cigarette with lipstick on it?

J.S.: Sure.

Joan: Other women?

He nods.

Joan: So you should be used to it by now. (Pause) You like my cowboy blouse with pearl snap buttons?

J.S. (Cautious): Sure . . . it’s nice.

Joan: Thanks. Reminds me of Texas.

They are silent for a while, both smoking, Joan looking out the passenger window.

Joan (Suddenly, turning to him): You remember prizes for the kids?

J.S. (Softly): In the trunk.

Joan (Relieved): Thank God!

J.S.: Lassos for the boys, cowboy hats for the girls.

Joan: How many?

J.S.: Three of each – one for the winner in each age division.

Joan (Looks front, pause): Wish we’d gotten enough so each kid could have a gift.

J.S. Forty, fifty of them. It’s a big camp.

Joan: I don’t care – hate to see kids disappointed.

J.S.: Might be able to stop along the way, pick up something else. I bought penknives for my boys – in a pinch we could give those away, too.

Joan (Looks at him appraisingly): John, you know anything about kids?

J.S.: I hope so. I have two.

Joan: I mean little kids. Responsible adults don’t let little kids play with knives.

J.S.: Too bad – they could play mumblety-peg.

Joan (Drily): Sure – take a toe off. I played that game growing up.

J.S.: Really?

Joan: You think I wasn’t a kid? (Pause) What’s your game again, the one we want them to play . . . something to do with frogs?

J.S. Lizards.

Joan: Okay, lizards.

J.S. (Smiling at the thought): It’s called “Big Lizard, Little Lizard.”

Joan (Nervously inhaling and exhaling smoke from her cigarette, repeating phrase as if memorizing lines): “Big Lizard, Little Lizard.” You think there’re enough lizards running around that camp to keep fifty kids occupied?

J.S.: You only have to reach down. Especially in the riverbeds. When I was a kid we found them along the Salinas River . . . if you knew where to look. Thicker along the Carmel River than the Salinas – hotter there.

Joan: I don’t know – Texas lizards weren’t all that easy to catch.

J.S. (A touch surprised): Did you try?

Joan: Sure! I was a gutsy kid – but we didn’t make a game out of it the way you did.

J.S.: The trick is to catch the biggest and smallest ones without losing their tails. Grab it by the tail, you lose it. (Pause) Do you think Kristin will play?

Joan: Don’t know. She’s game, but may run like hell when she sees me.

J.S. (Looks at her, mildly surprised): You didn’t tell her we were coming?

Joan: Eyes on the road, please . . . . If I had, she’d be gone for sure, or pretend to be sick . . . done it before, other camps . . . . (Snubs out her cigarette, pulls her feet up onto the seat, her arms around her knees. Moodily) Anyway, rather not talk about it if you don’t mind.

J.S. (Snubs out cigarette): How old when you adopted her?

Joan: I told you I didn’t . . . .

J.S.: Okay . . . .

Joan (A beat, softening): Another cigarette?

J.S.: Yes, please . . . .

Joan (Fishing a cigarette out of the pack): I’ve heard her friends talking about me . . . upstairs, in Kristin’s room . . . things they’d never say about their own mothers . . . and the really insulting thing – don’t seem to care if I hear them . . . . Guess what I do for a living makes me fair game . . . easy target . . . . (Stretches her legs, lights cigarette) Why’d you slow down?

J.S.: Did I?

Joan (Handing him cigarette): Noticeably. Let off the gas. Was it that sign we just passed – so many miles to Salinas?

He takes cigarette, nods.

Joan: Reflexively? Not intentionally?

He nods again.

Joan: So why does it make you nervous?

J.S.: Don’t you get nervous when you’re going home and it’s been a while? Returning to your past?

Joan: We’re not going all the way to Salinas, are we?

J.S.: Close enough. We’ll be skirting to the south. Anyway, they know me everywhere in the valley . . . .

Joan: And you don’t want to be seen?

J.S.: Hell no!

Joan (Studies him, pause): People don’t forget, is that it? Things you’ve written? You think trouble, you’ll get trouble. Believe me, I know . . . that’s why I’m trying to stay hopeful about today . . . .

J.S.: But tense?

Joan: Sure, but thinking good things . . . . I want to be positive. . . . I swear to God, it’s going to work this time – she’s going to like me. (Looks out passenger window) Anyway, thought you’d been back since then.

J.S. Not driving up the heart of the valley middle of the day. Haven’t done that with a woman since Carol and I were young and poor and nobody gave a damn what we did or who we were with . . . . Didn’t know how lucky we were . . . . If we got pulled over it was because a taillight was out or something . . . or a cop needed to meet his quota. Simple things.

Joan: What route you take now?

J.S.: Fly into Monterey middle of the night . . . little single prop . . . come in from the north – San Francisco. Have a pilot, a friend – James. We get to the house when it’s still dark, maybe no one knows I’m around for a while. (Pause) This route – we go through every little town, stop signs in all of them . . . . I make too much a full stop someone might recognize me . . . . I don’t make a full stop, cops or deputies probably pull me over. When they realize it’s me . . . .

Joan: Then what happens?

J.S.: Nothing I look forward to . . . and once word gets out . . . .

Joan: And here you are . . . riding with good old identifiable me. Knew you were trying to tell me something back there. Well, you are, too. Identifiable, I mean.

J.S.: Not like you.

Joan: No? I’ve heard people say they can spot those feverish blue eyes of yours a mile away. Maybe the cops can, too.

He laughs, embarrassed.

Joan: So, why’re they feverish?

J.S: Don’t think they are.

Joan: Well, mine need a little rest – I usually doze through makeup and it’s past time now.

She leans back, closes her eyes. Lights dim to dark, then come back up. Her eyes are still closed. He is smoking. He stretches, yawns. She opens her eyes, rubs them, looks at him.

Joan (Smiles warmly): Hello.

J.S. Hello.

Joan: Suppose I was tired after all. You lit your own?

J.S.: I can do feats of magic.

Joan: I guess! (She looks out passenger window to the right, looks away, looks again) Your river down there?

J.S. (Nodding): The Salinas River. Been seeing it a few minutes now. Flows south to north, same as the Nile. Not many do. Both valleys rich in topsoil. Maybe something to that – flowing south to north . . . both being fertile valleys.

Joan: Fertile for you, too, this river.

J.S. (Subdued): I don’t know.

Joan (Pause): It’s where the big guy was killed, right? Down by that river?

He looks off, uncomfortable.

Joan: Isn’t it?

John (Mumbled): Yeah . . . little farther north.

Joan: See, I do read you. Want to know something? Your book made me cry. I’ll tell you why – his friend in a way adopts him . . . looks after him like I try to look after my daughter . . . when she lets me . . . . (Pause) Anyway . . . . (Pause, looking out, momentarily dispirited) Anyway, not much water in that river of yours, is there?

J.S. (Glad to be off the subject of his writing): Can’t tell a lot by looking. Underground flow, the Salinas. You have to look at the country around to get an idea if underground flow is meager . . . or maybe even dried up. That’ll tell you. (Glancing to the left) The trees . . . .

Joan: What are they?

J.S. (Pause): Mostly oaks – live oaks.

Joan: They don’t look very live to me.

J.S.: Don’t be fooled . . . you think they’ve about had it, they bounce back . . . they’ll be here when we’re long gone . . . . Anyway, grass tells the truer story. It’s brown, so, yes, river’s looking bad . . . probably dried up underground, too. (Looking past her to the right) And there . . . .

Joan: Where?

J.S. (Pointing): A kind of chapparal – okay if you’re desert country, but we’re not . . . not supposed to be, anyway . . . . There, dust devils kicking up topsoil . . . carrying it off . . . breaks the farmer’s heart . . . then another dust devil brings topsoil to his field from a neighboring farm and he feels better about it . . . better about his god. Evens out, sort of. Third year of drought, they say. Aquifers drying up.

Joan (To the right): And those men?

J.S.: Oil fields, recent discovery – just putting in the pumps, I’m told.

Joan (Gazing): Moving slowly . . . the men . . . .

J.S.: . . . well, you can see the heat rising . . . .

Joan (Pause, somewhat sensuously, to herself): Primal . . . .

J.S.: What?

Joan: Primal . . . . (Shakes herself) Sorry – thinking aloud. (Lighting a cigarette) Didn’t know I was.

J.S.: I do that. Can get you in trouble.

Joan (Laughs): Tell me – my life story . . . . (Pause) Did we pass through a place while I was out?

J.S. (Nodding): San Miguel.

Joan: Mission town?

J.S.: Yep.

Joan: Wish you’d told me . . . of course, you’re glad I was sleeping.

J.S.: Uh-huh . . . .

Joan: Anyone look at you suspiciously in San Miguel? A padre, somebody like that?

J.S. (Laughs): I stared straight ahead.

Joan: Anyway, you worry too much.

J.S. (Watching the road, considers, then flatly): Dostoevsky . . . .

Joan: I’ve read him, too . . . . And so?

J.S.: In front of a firing squad . . . .

Joan: And?

J.S.: . . . called off the last second . . . .

Joan: That happen to you?

J.S. Something like . . . not so formal . . . .

Joan: What you write about, right? That’s the reason? Why don’t you write about something else? The world has lots of problems that don’t call for shooting the writer.

J.S.: I’ve tried. Not as good – not me.

Joan: Well, you’re persistent alright . . . . So am I – I’m not giving up on my relationship with Kristin . . . a mother can’t do that . . . it’s damn well going to work.

J.S. (Notices something, begins to let his foot up on “gas pedal,” nervously): San Ardo. . . feed store . . . farmers come in . . . maybe only one stop sign . . . not sure, been a while . . . .

Joan: That’s good for you, isn’t it – just one stop sign?

J.S.: . . . the fewer stops, uh-huh . . . .

Joan: I’ll look down. (Can’t resist) Don’t run the only stop sign in San Ardo . . . .

J.S. (But tense): Funny.

He lets his foot off the “gas pedal,” then presses down on the “brake.” He looks straight forward, head inclined. They come to a stop. She lifts her head slightly.

Joan: It’ll look suspicious you stay stopped too long . . . .

J.S.: Quiet, lady.

He accelerates slowly. She waits.

Joan: Okay if I come up for air?

J.S. (Relaxes): We’re back on the highway.

Joan (Straightening): Anyone look at us suspiciously?

J.S.: A few.

Joan: Tall guy in a denim shirt one of them?

He glances at her.

Joan: I peeked. He was staring alright – because this is a pricey car. I recognize the look. Most of these people except land owners are dirt poor. You should expect them to stare at a ritzy car.

J.S.: It’s an Oldsmobile.

Joan: To a fieldworker, that’s ritzy. (Lights a cigarette) You want one – a cig, I mean?

He nods. She hands him hers.

Joan (Lighting another for herself): As a kid in Texas I stared at big cars – because I wanted one. Who was inside, I didn’t give a damn. I’ll bet that guy in San – San – ?

J.S: San Ardo.

Joan: Bet he feels the same way. Wants the car, doesn’t give a damn about you or me.

J.S.: My kind of guy . . . .

The lights dim, then come back up, J.S. turning his head, searching the countryside. Joan has taken off her shoes, which are on the “floorboard.” Looks at her feet, then raises one of her hands and looks at it critically. Then watches him.

Joan: What’re you looking at?

J.S. (Subdued enthusiasm): Just the valley . . . got an idea . . . .

Joan: About what?

J.S.: Something I might write . . . translating the land into images . . . in my head.

Joan: That’s what you do?

J.S.: Try . . . lately abstract images . . . gotten lazy, I guess . . . learned it from painters . . . where a lot of abstraction comes from, you know . . . . The viewer can imagine his own detail . . . and so can the reader . . . but been a long time since I’ve seen . . . (Pause) . . . been able to look at . . . at this valley . . . .

Joan: A story coming?

J.S.: Maybe.

Joan: Another novel?

J.S. (Pause): . . . no longer the staying power . . . .

Joan: (Looking out her window, after a few moments): Well, you’re lucky you’re a writer . . . not an actor.

J.S.: What brought that up?

Joan: Don’t know.

He looks at her.

Joan (Pause): Sometimes . . . when I see myself in a film, I feel I’m looking at a corpse . . . my corpse . . . it all seems dead, the story, the other characters, everything . . . even the lame so-called sexy bits . . . . Is that pitiful?

J.S.: I’m sorry.

Joan: Not that way for you – reading one of your books?

J.S.: I don’t do it.

Joan: Smart. (Pause) When did you acquire this fear? Or is it paranoia?

J.S.: When a contract was put out to break my legs, if you call that paranoia.

Joan: That happened?

J.S.: Sure.

Joan: When?

J.S.: One of many threats . . . they stay with you . . . work on you . . . chip away . . . people say forget it, but impossible to put out of your mind, no matter how long ago . . . (Tense, suddenly focuses) Bigger town coming up. Couple stop signs . . . feed store, so farmers come in . . . used to be, maybe still – a sheriff’s substation.

Joan: Cigarette before?

J.S.: No time . . . (Worried) . . . snuck up on me. Been away too long.

He begins to let his foot up on the “gas pedal.”

Joan (Loosening her hair, staring front blankly): I’ll be good . . . .

He glances at her, begins to laugh, loses concentration, quickly “puts on brakes” – for the first time, a slight squealing sound.

Lights to dark, then back up. J.S. looks stricken. Joan is watching him drive while tying back her hair.

Joan: Have a bobby pin?

J.S. (After a few moments, staring straight ahead): Don’t ever do that to me again.

Joan: What? Be myself?

J.S.: You know what I mean.

Joan: You think being myself is easy? For a great writer you’re having a lot of trouble reading me. Anyway, what you’re really saying is don’t make you laugh . . . . Wonderful hearing you laugh, even choking it back while hitting the brakes.

J.S.: I could have killed somebody.

Joan: There wasn’t anyone.

J.S.: There could have been.

Joan: That was either a ghost town or everyone’s home having lunch. Anyway, shouldn’t we do what they’re doing – have ours?

J.S. (Pause): Not a good idea.

Joan: Oh, right, I forgot – you might be seen.

J.S.: That’s not it.

Joan: No?

J.S.: No. We’re getting close.

Joan (Sudden change of mood, softly): Are we . . .?

J.S. (Nods): In the distance – that’s Monterey Bay.

She looks.

J.S.: Matter of minutes.

Joan: Oh.

She lights cigarettes for both of them in the silence.

Joan (Handing him his): Feel safer now?

J.S.: A little.

Joan: Good – something good . . . .

A long silence as they smoke.

Joan: I forgot my fear for a while . . . the towns . . . fields . . . the river and oaks . . . . . . like . . . like an Eden . . . (Pause) Remember what I said about seeing myself that way on celluloid? Do you think that’s the way Kristin sees me? If I see myself that way, why shouldn’t she?

J.S.: You’re very much alive.

Joan: Maybe if I’d had a normal life . . . a normal career . . . but how many normal careers are there for women that amount to anything? I’d be a lousy nurse.

He smiles, makes a sharp turn to the left. They bounce a bit because of the road.

J.S.: Potholes.

Joan (Some fear): We’re there . . .?

He pulls to a stop. They look out and down, moving up in their seats, she slowly, anxiously.

J.S.: There – bottom of the hill . . . other side of the gate . . . there’s your camp . . . lots of boys and girls. (Pause) Can you see her?

Joan (Leaning forward): Hard when they’re running and playing . . . . No . . . no . . . (Softly) Oh, God, yes . . . there she is – blonde . . . blue shorts . . . alone under one of your live oak trees.

J.S. (Sees her too, smiles): Little bit tomboy?

Joan (Smiles): Little bit.

J.S.: Ready?

Joan: . . . let me take a deep breath.

J.S.: We can come back later if . . . .

Joan: Have to do it now. (Regains some composure) Tell me again the name of that game . . . .

J.S.: “Big Lizard, Little Lizard.”

Joan (Fervently): And the best place to find these lizards?

J.S.: Riverbed . . . if not sunning, then under stones and rocks . . . .

Joan: . . . if she doesn’t run from me . . . . She did once. . .

J.S.: She won’t this time. You’ll both be fine. (Waits) Okay? . . .

She nods.

J.S.: You’re sure?

Joan (Trying to convince herself, primping her hair, gaining composure, looks at him): I do this for a living, don’t I? . . .

He nods.

Joan (Takes a deep breath, with authority): Well?

He nods again, then presses the “accelerator” gently as they begin down the hill. She is smiling, seemingly full of confidence. The sound of children playing grows closer, louder.

Blackout.

IV

Manhattan

1965

J.S., in his early sixties, at his writing desk in his New York City apartment. Several pads of lined yellow paper and unopened letters on his desk. A hallway stage left, the front door to the apartment stage right. In the back wall, but not directly behind him, a window looking out onto the dark; some illumination from city lights. It is late night.

A bookcase close by. On top, a tape recorder, lighting making it more noticeable. He snubs out a cigarette, looks at recorder. He clicks it on, clears his throat, changes his mind, clicks it off.

He is tense. Picks up a letter, puts it down. Turns and stares at the window. Stands, goes to it, looks out. Paces, return to desk, opens a letter. Leans forward, reads to himself.

Hears a sound from outside the door, starts, gets up, goes to door, listens, tries knob to make sure it is locked, returns to desk, sits, opens desk drawer, pulls out a revolver. Checks if it is loaded, sets it on the desk. Picks it up again, checks it again, smiles at his fear, returns it to desk top, facing the barrel toward the door.

Picks up yellow tablet, looks at something he has written, takes a pencil, adds a word or two, scratches one out, clears his throat, reads from it:

J.S.: “He felt it intensely . . . in the tainted land, by the river, in the wind rustling the oak leaves . . . .”

Looks at tape recorder, considers, switches it on, a slight whirring sound.

J.S. (Looks at tablet, clears his throat, reads again): “He felt it intensely . . . in the tainted land, by the river, in the wind rustling the oak leaves . . . a kind of evil – “

A Man’s Voice (Interrupting): John, who’re you talking to?

He starts, looks up from his tablet. The Gaunt Man is standing downstage, half in and out of the light, in overalls, chewing on a toothpick.

J.S.: Tom.

Gaunt Man (Laughs): First time I scared you!

J.S.: Nah, you didn’t scare me.

Gaunt Man: You sure ‘n hell jumped! (Grins) Something you wrote maybe – scare yourself?

J.S. (Smiles): I’ve done that.

Gaunt Man (Moving into full light): Damn good writer can scare himself.

J.S. (Furtively covering the revolver with a yellow pad): Well, I admit you surprised me, Tom – it’s been a while since your last visit.

Gaunt Man: You were doing okay there for a time – didn’t think you needed me.

J.S.: Don’t take this wrong, Tom, but don’t think I do now.

Gaunt Man: Course you do or I wouldn’t be here – you called for me.

J.S.: You always say that . . . .

Gaunt Man: ‘Cause it’s true. (Chews on toothpick, shakes his head) Beats me why anyone’d question those gone before them! Like a child questioning how her mama shells peas. Makes no sense. The child never shelled a pea – and you never been where I’ve been. (A beat) What’s that there?

J.S.: What’s what?

Gaunt Man (Pointing at the tape recorder): That – that thing goin’ round.

J.S.: Oh, that’s called a tape recorder. I didn’t have it last time you visited?

Gaunt Man: I’d sure remember something goin’ round like that . . . . It do anything else?

J.S.: Copies your voice . . . . When you play it back, you can hear what you just said.

Gaunt Man: If you just said it, what’s the point?

J.S.: Well . . . .

Gaunt Man: Why not just get a parrot?

J.S.: I got a talking myna bird, Tom, why would I want a parrot?

Gaunt Man (Looking around): Thought it was quiet in here. Where is he – where’s John L?

J.S. (Fingers to lips): In the bedroom. Don’t get him started. He kibitzes, I kibitz back, nothing gets done.

Gaunt Man: Keeping Elaine up?

J.S. (A beat, rather not say, mumbles): Elaine’s gone a few days.

Gaunt Man: Texas?

J.S.: Yeah.

Gaunt Man (Pause): So that’s what you were doing when I came in, copying your voice?

J.S.: Well . . . .

Gaunt Man: Tell me about it.

J.S.: It’s like a Dictaphone machine, Tom – you ever hear of those?

Gaunt Man (Nodding): Sure, like a parrot.

J.S. (Nettled): Yeah, but you don’t have to be so close to be recorded – this thing can hear you clear across the room.

Gaunt Man: So can a parrot. This something new in the world?

J.S.: Been around but getting more affordable.

Gaunt Man: Even for Okies?

J.S.: Not back then. But if they can afford a radio, they can probably afford one of these.

Gaunt Man (Staring at it): But is it a waste of money? . . .

J.S.: Don’t know . . . still trying it out.

Gaunt Man: To do what?

J.S.: I read the words I’ve written into this, to see how they sound when spoken.

Gaunt Man: That’s what you were doing when I came in?

J.S.: Starting to . . . .

Gaunt Man: That so important, how the words sound? Do your readers read your writing out loud? Isn’t that for children’s books?

J.S. (Irritably): Listen, Tom . . . .

Gaunt Man: I don’t get it, that’s all.

J.S.: It’s a rhythm thing probably more than a tone thing.

Gaunt Man (Skeptical): Uh, okay . . . and what’s the excuse for the gun under your writing pad . . . or do you think I missed that Houdini move of yours?

J.S.: That, Tom, is none of your business.

Gaunt Man: Come on – you wanted it seen, so talk about it.

J.S. (Stands, paces): I didn’t want it seen, and I don’t want to talk about it.

Gaunt Man: You sure about that?

J.S. (Felt): I’m clumsy, that’s all. Always been, you know that. (Suddenly morose) Sorry, just tired . . . taking it out on you.

Gaunt Man (Curious, cocking his head): Tired? You are the one man I know never gets tired. What makes you tired now?

J.S.: Riling people, I guess.

Gaunt Man: Hell, John, riling people makes you tick!

J.S.: Well, then, tired of people I riled threatening me and mine.

Gaunt Man: That happen?

J.S.: All my life.

Gaunt Man (Pause): Recently?

J.S. (A beat): Uh-huh.

Gaunt Man (Pushing): When?

J.S.: Few days ago . . . .

Gaunt Man: That’s why the gun?

J.S.: Had guns before, after those boys came after me in California – just about the time you were coming into being.

Gaunt Man: I know that story alright, you told me enough times. The fields by the river, then by that old oak tree, gun at your throat. They kill you – no me, no Tom, no book. Old stuff. This is new – tell me about this one.

J.S.: Not much to tell – guy calls – soft voice – says, “Don’t think you’re safe just because you’re three thousand miles away. I’m coming for you.”

Gaunt Man (Grinning): Maybe a bill collector?

J.S. (Laughs): Could be.

Gaunt Man: Anything more he says?

J.S.: The usual – calls me a Commie bastard. (Ruefully) Well, J. Edgar’d agree with him – least the Commie part.

Gaunt Man: Hoover?

J.S.: Yeah.

Gaunt Man: Then what? – about the call, I mean.

J.S.: Nothing more . . . just quiet, then hangs up.

Gaunt Man (A beat): Call’s from California?

J.S.: Three thousand miles . . . works out . . . unless . . . .

Gaunt Man: Yeah?

J.S.: Unless he’s already here . . . the three thousand miles remark maybe making me think I’ve got some time . . . be clever of him.

Gaunt Man: Why would he warn you?

J.S.: Personal enjoyment.

Gaunt Man (Thinks): Yeah, I’ve seen that.

They are silent a moment.

Gaunt Man (The gun): Why you have this ready to go?

J.S.: Be a fool not to, Tom.

Gaunt Man (Studies him, chews on toothpick): You get lots of threats, why this one in particular bother you more’n others?

J.S.: The softness of the voice . . . something about it . . . reminded me when I was a kid and a slow wind blew up the valley, rustling the leaves of an old live oak tree outside our parlor window . . . or down by the river . . . blowing over the surface of the water could lift hair on back of the neck . . . (Goes to window, looks out, pause) In the afternoons, in the spring, day after day. Don’t know why, but made me anxious . . . felt like they were talking to me, those brittle oak leaves, telling me things I didn’t want to hear. This voice had that quality, and then, well, Tom, kind of a funny thing . . . .

Gaunt Man: Funny?

J.S.: Hoover’s men tailing me . . . been driving me crazy lately – but since that call a few days ago, glad they are . . . . When I feel I am being followed like this afternoon, and see it’s one of Hoover’s boys with neatly parted hair, I breathe easier glad it’s not a killer . . . Hoover’d hate knowing he’s giving me a sense of relief.

He looks out window meditatively. The Gaunt Man shifts his weight, restless.

Gaunt Man: Watching you now? . . .

J.S. (Moving away from window toward desk): Across the street . . . government’s renting a hotel room . . . a suite, probably . . . . couple weeks now.

Gaunt Man: Watching you through that window?

J.S.: Yep.

Gaunt Man: John, you been drinking? (Goes to window, hand in an overall pocket, chewing on his toothpick; looks out) Just a big building.

J.S.: A hotel. They’re there, Tom. Third floor, fourth window from the left – straight across.

Gaunt Man: Dark.

J.S.: Always is.

Gaunt Man: You’re cool for a man being investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

J.S. (Shrugs): Used to it – they’ve investigated me since the ‘30s.

Gaunt Man: They’re persistent alright.

J.S.: So am I.

Gaunt Man: More stubborn, you ask me. Got anything on you?

J.S.: Not much.

Gaunt Man: Whole lot of work for nothin’ then. (Looks out again): Think they’re watching me now?

J.S.: Better question is, can they see you?

Gaunt Man: You mean ‘cause I’m what people call an apparition?

J.S.: That’s what I mean.

Gaunt Man: Maybe I should wave . . . . What floor you say?

J.S.: Third floor, fourth window from the left . . . almost straight across . . . .

Gaunt Man: You mind?

J.S.: Go ahead.

Gaunt Man (Waves lazily, waits, turns:) And if they saw me? . . .

J.S.: Immediate report to J. Edgar – he’s with a Commie in farmer’s overalls. Hoover’d say adds up – very proletarian.

Gaunt Man: Why don’t you pull the curtain?

J.S.: Sign of weakness.

Gaunt Man: Wouldn’t give them that?

J.S.: Hell no!

Gaunt Man: But you’re glad they’re watching you now?

J.S.: Someone kills me in this room, maybe they’ll see it, get the bastard . . . get my body out of here before Elaine gets back, that’s the important thing. (A beat) Hoover long ago . . . my California days. . . wrote me . . . said there were people wanted me silenced . . . .

Gaunt Man: You take that as a threat?

J.S.: No – just wanted me for himself . . . be the one to get me to crack . . . wrote back thanking him . . . probably embarrassed he might have done something decent.

Gaunt Man: This why Elaine’s gone? For your woman’s safety?

J.S. (Nodding): Sent her off for a while.

A Voice (From off, plaintive tone): Elaine! Elaine!

They both look toward hallway.

J.S.: Elaine’s his favorite.

Gaunt Man: Bring him out?

J.S.: I don’t want John L here . . . not now . . . .

Gaunt Man: The man with the soft voice?

J.S.: Be the same as a child seeing it . . . animals sense death better than we do . . . maybe he’d harm John L . . . find pleasure doing that, too.

A Voice (Pleadingly): John! Elaine! John!

Gaunt Man (Pause, gesturing toward John L’ s voice): Hard to ignore him.

J.S.: Want him to get used to us not being at his beck and call.

Gaunt Man: You goin’ somewhere?

J.S.: Flying to Europe with Elaine. Maybe after I’ll push on to Vietnam . . . traveling a lot. Not fair to John L. We’re looking for a new home for him. (Pause) We’ll miss John L.

He looks off, embarrassed, almost absently picks up the revolver, studies it, then hefts it.

Gaunt Man: Getting ready?

J.S.: Hope it doesn’t come to this.

Gaunt Man: How’s it feel?

J.S. shrugs.

Gaunt Man: Colt?

J.S.: Got two, one for here, the other . . . (Pats his chest) for carry.

Gaunt Man: Licensed?

J.S.: (Nodding): Wasn’t easy – judge had questions.

Gaunt Man: Character witnesses?

J.S.: Had to scramble. Some backed off – afraid of being linked to my name. That hurt . . . .

Gaunt Man: . . . should have expected . . . .

J.S. (Nodding): Did . . . hurt anyway, you know? . . . One signed without hesitation – John L’s vet in Nyack, man named Morris Siegal . . . makes sense, I’ve always done better with animals than people . . . and people who love animals . . . .

A Voice: John L’s hungry! John L’s hungry!

J.S: (Calling): Be there soon, John L . . . . (Pause) The Irish have this belief, if there’s a bird in your home day after you pass on, your soul flies free . . . .

Gaunt Man turns away, chews on toothpick.

J.S.: . . . they say a wild bird . . . but not many given the chance won’t take flight.

Gaunt Man (A beat, considering): Tell you, John, I hear what you’re sayin’, but freedom’s never done much for me . . . .

J.S.: Tom?

Gaunt Man: Hell, I’m free . . . look at me . . . can go anywhere I want . . . no restraints . . . but I killed a man. . . can’t get that out of my head no matter what I do or where I go.

J.S.: Tom, I wrote that. . . part of your story, that’s all.

Gaunt Man: Don’t like that part.

J.S.: Thought we talked this out long time ago.

Gaunt Man: Talkin’ don’t make it go away.

J.S.: He would’ve killed you, Tom.

Gaunt Man: Didn’t have to make me kill him – that’s all I’m saying. You could have thought about that before putting it down on paper.

J.S.: (Pause): You bump into him out there? That happen?

Gaunt Man: Not yet . . . someday.

J.S.: He’d want revenge?

Gaunt Man: We’re not allowed revenge . . . express ourselves, can do that . . . I’ll hear from him, I know that . . . .

J.S. (Pause): I’m sorry, Tom.

Gaunt Man (Looks away): It’s okay . . . I’m tired, that’s all . . . . so, takin’ it out on you, just like you done me a little ago.

J.S. looks at him with sorrow. There is a silence, then:

The Voice: John L’s lonely! John L’s lonely!

Moved by this, J.S. turns away, looks out window.

J.S.: Would have liked John L here when I die. Named him after John L. Lewis . . . champion of the working man . . . You know that, Tom?

Gaunt Man (Reluctantly, dry): Afraid you’ve mentioned it a time or two.

An awkward silence, then –

J.S. (Laughs): Guess I have!

Gaunt Man (Grins): I’m as bad – nothing so easy as fooling a storyteller.

J.S. (Curious): About what?

Gaunt Man: It’s tough out there, but not so tough as I make out.

J.S.: Same for me, I guess.

Footsteps heard. Then silence. They look at each other, then toward the door.

J.S.: You’d better go . . . in case . . . .

Gaunt Man: I’m not leaving.

J.S.: You can’t interfere – not allowed.

Gaunt Man: Not leaving, I said.

J.S.: Would destroy something, some kind of balance . . . . you know that.

Gaunt Man (Pauses): You have a plan?

J.S.: None.

Gaunt Man: You ever shoot a man?

J.S. (Anxious, shakes his head): No.

Gaunt Man: And all these years armed! First thing is steady your hand – it’s shaking and you’re not even holding the gun.

J.S. picks up the gun, tries to steady his hand.

Gaunt Man: Better. (Looks around) Keep the curtain open – your witnesses could be the FBI. (Looks around again) And keep that parrot machine goin’.

J.S. (With relief puts gun back on desk): So maybe it’s good for something after all . . . .

Gaunt Man: If it works, another witness. You think it’s hearing me now?

J.S. (Moving to it): A way to find out . . . .

Gaunt Man (Indicating door, stepping back): Not now – no time – should have asked sooner.

J.S.: Should have . . . .

Gaunt Man: . . . if you don’t make it, guess I’ll never know . . . .

J.S.: Next time . . . .

Gaunt Man: If there is . . . .

The Gaunt Man stepping back disappears into the darkness.

J.S.: Tom . . .?

The Voice: John L’s lonely, John L’s lonely.

J.S. (Moving toward the voice, softly intense): Coming, John L. Now you be quiet, you hush in there . . . .

Turns, approaches desk, looks at tape recorder, puts it on rewind and as it rewinds shakily places the revolver facing the door. The recorder lurches to a stop. He flips the recorder to play. After several seconds of silence:

J.S.’s Voice: “He felt it intensely . . . in the tainted land, by the river, in the wind rustling the oak leaves . . . a kind of evil – “

The Gaunt Man’s Voice (Interrupting): John, who’re you talking to? . . .

J.S., fumbling but with a small smile, flicks the recorder off.

He looks toward the door as it is tried again and puts his hand on the gun as the lights dim to dark.

End of Play

© 2021 Steve Hauk