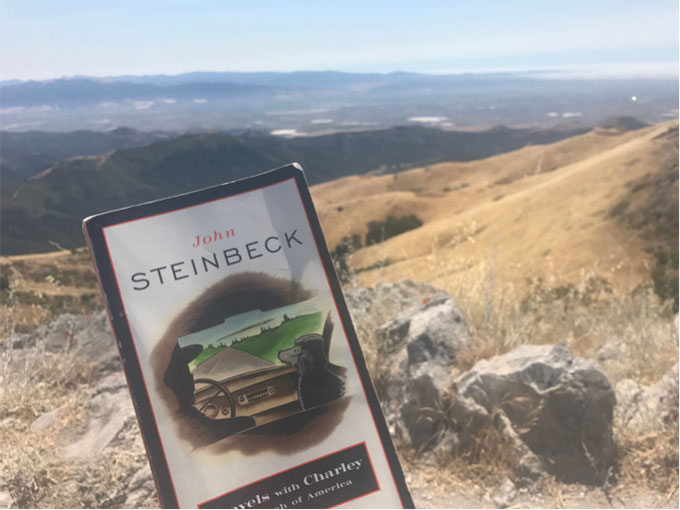

Inspired by his reading of John Steinbeck and William Faulkner, Carter Johnson writes about the universal human condition, man’s relation to nature, and the texture of rural American life in “Dogwood Lullaby,” the collection of poems, essays, and short stories, centered around life in Appalachia, from which these examples are taken.—Ed.

Lore the Scrivener

The pond is dark below the rippling rings,

Where creeps the old and long forgotten Lore,

Who guards the mountain’s dreams under the shore,

A scrivener, noting what the warblers sing.

The civic fish know Lore and nothing more.

They learn the learnless lessons all must glean,

To swim and hunt and do what’s done before,

Beneath their rolling sky of milky green.

Lore keeps a book that counts the fish of God,

That live and die and feed the net of life.

Whose bones will sink into the mud or sod,

As water chases shore with endless strife.

Into this world we throw our hooks and wait,

And watch the ripples of our swallowed bait.

The Young Knights of Elliston

The dull hum of the lawnmower perturbed the evening. It was nearly six, but the July heat refused to relent. It clung to the ground and the trees and the mailbox. Everything was stuck in the clutch of the hot stickiness. Over the last week, there had been no rain, only waves of heat, rolling off the concrete and radiating into the atmosphere. The hot air rose, bounced off heaven, and blew back even hotter the next day.

Mr. Brewer jiggled on his riding mower. He was a big and hairy man. He had thick blonde hair covering his chest and back. You wouldn’t notice the coat from a distance, but when you got closer, the golden fur clung to him like moss on a rock. He was overweight, but his former-football-build held the extra hamburgers in a somewhat acceptable fashion. He had a gold coin on a chain around his neck. The little emblem was mostly concealed by the fur. As his mower spit grass into the street, his belly rattled with every bump. In his left hand, he held a Mountain Dew. With his right, he scratched his stomach. Little pieces of grass would kick up and get caught in the hairy net. He was covered in sweat. He wiped his face with a drenched bandana and stuffed it back into his pocket. He was happy.

As the grass fell under the blade, two shadows moved in the tree line. Only a flash of red could be seen through the dense bushes and tall grass. Mr. Brewer did not see the phantoms. He continued to cut the field with increasingly smaller NASCAR circles. He swatted a few gnats from his brow. The phantoms stalked closer.

Young Tom Sinclair crept barefoot. Tom was thirteen at the time, and his companion, Will, was fourteen. Will’s dark hair made him less visible behind the shrubs. Additionally, he liked to stay hidden behind Tom, who offered protection with his new BB-gun. Tom had green eyes and red hair, inherited from his great grandfather. He was afraid of two things: his older brother and leaving Elliston. The first fear was frequently faced if only to confirm predictions. Tom’s fear of his older brother Reggie was mostly out of respect for ability. It was a fear that prompted escapes from headlocks and mudballs. As he grew older, Tom prodded the bear more frequently and with greater force. Most of the time, Tom left with a scraped knee or a sore arm. Occasionally, he would leave a tearful and defeated antagonist. Yet, some attacks were unprovoked. These were the instances that created Tom’s true fear of Reggie. One night, while Tom was sleeping, Reggie blindfolded, hogtied, and gagged him. He carried Tom to the pig pen and threw him into the mud. When Tom finally wrestled himself free, he stormed into his brother’s room. Full of fury, Tom started throwing punches. Reggie tossed him into the dresser and the two rolled around on the floor. Tom was overmatched. Their father entered the room, concerned about a potential emergency. He quickly recognized the situation. The boys froze. His nightshirt was luminescent with anger. He grounded Reggie for two weeks and gave him extra chores, a soft punishment in Tom’s eyes. Tom got a stern conversation about revenge. It was drawn from the Sermon on the Mount and left Tom confused.

Tom’s second fear was more substantial. He loved his home. He loved the mountains. He loved the streams. It terrified Tom to think about moving away. Tom wanted to roam barefoot forever. Specifically, he wanted to roam with Will. Will followed Tom on every adventure. Whether passing notes in class or trying to get fishing line untangled, the boys were inseparable. When they played knights, Tom was always King Arthur and Will was Sir Lancelot. The roles were fitting, although the boys didn’t know about the end of the story. Plus, Sally Compson wasn’t as alluring as exploring a new trail.

Beneath the cover of the lawnmower’s monosyllabic song, the two boys hid behind a log. Tom’s steadied the BB-gun on a V-shaped branch.

“I don’t know about this.” Will looked over his shoulder into the woods behind them. “We could get in trouble.”

“Shut up, Will. You’re always scared of getting in trouble. It’s not that bad.”

“Not that bad?”

“No.” Tom looked down the sights.

“My Dad will give me the belt for this . . . Tom, are you even listening?” Will punched Tom in the arm. The BB-gun slid from its perch.

Tom punched back. “Geez, Will. Cut that out.” He cleared some leaves and twigs from his seat and placed the weapon back on the branch. “We aren’t going to get in trouble. Calm down.” Tom drew a bead on the albino sasquatch, following the target as the lawnmower carried it away. Tom lowered the BB-gun and wiped his nose. “We have to wait until he makes the turn near us.”

“Tom, I don’t like this.” Will looked over his shoulder again.

“What are you looking at?”

“Just checking.”

“There’s no one out here, Ok? Relax.”

Will rubbed his hands together. “Why can’t we shoot cans? That was fun.”

“Shooting cans is boring. This is . . . heroic.”

“What?”

“It’s saving the children he’ll eat this week.”

Will pushed Tom again.

“Quit it. Child lives are at stake.”

“I’m leaving.” Will stood up.

“Sit down! He’ll see you, stupid.”

Will quickly crouched behind the stump.

“Relax. Quit worrying.” Tom looked over the field. “He’s coming back.”

Mr. Brewer took a long draught of Mountain Dew. His shoulders were turning pink. Tom readied himself. He pressed the butt of the gun into his shoulder and squinted his eyes. Will watched the lawnmower creep forward.

“I’m aiming for the belly. It presents a large target.”

Will couldn’t help but giggle. For a brief moment, the humor bettered his worry. Then, his laughter mixed with his guilty conscience and made him feel worse.

Mr. Brewer made the turn. He was directly perpendicular to the boy’s position. Tom pulled the trigger. A small amount of compressed air propelled the pellet out of the muzzle. Its trajectory was precise and Tom’s aim was true. The BB hit the gelatinous fat three inches to the left of the naval. Mr. Brewer dropped his soda and gave a yelp. He couldn’t hear the BB-gun because of the lawnmower. He jumped off and examined the red welt, protruding from his pasty round stomach. After a cursing fit, he concluded that something stung him. The boys dashed into the woods. Tom grinned. Will couldn’t sleep for a week.

“East of Eden” photograph by David Laws