If the medium is the message, what does Facebook’s demeanor say about its dependent users? I don’t have boundaries—or enough to do to fill my time? I don’t have real friends, so pokes, shares and likes from fake ones fill my need to feel in touch? I don’t care if they sell my information because convenience is more important to me than privacy? Much as wish we could, we won’t delete Facebook from this website’s social media menu because some readers still use it to receive weekly post updates. But if you’ve tried reaching out to us there, we apologize for the inconvenience. We don’t respond to pokes and messages because we never liked the look and feel of the platform, or its potential for addiction and abuse. As explained in today’s report in The Hill on Facebook’s misappropriation of user data, recent events have confirmed our worst suspicions. If you decide to delete Facebook in protest, SteinbeckNow.com applauds you. You’re sending a message that the author who always preferred privacy to convenience would no doubt approve. Let us know when you do . . . but don’t use Facebook.

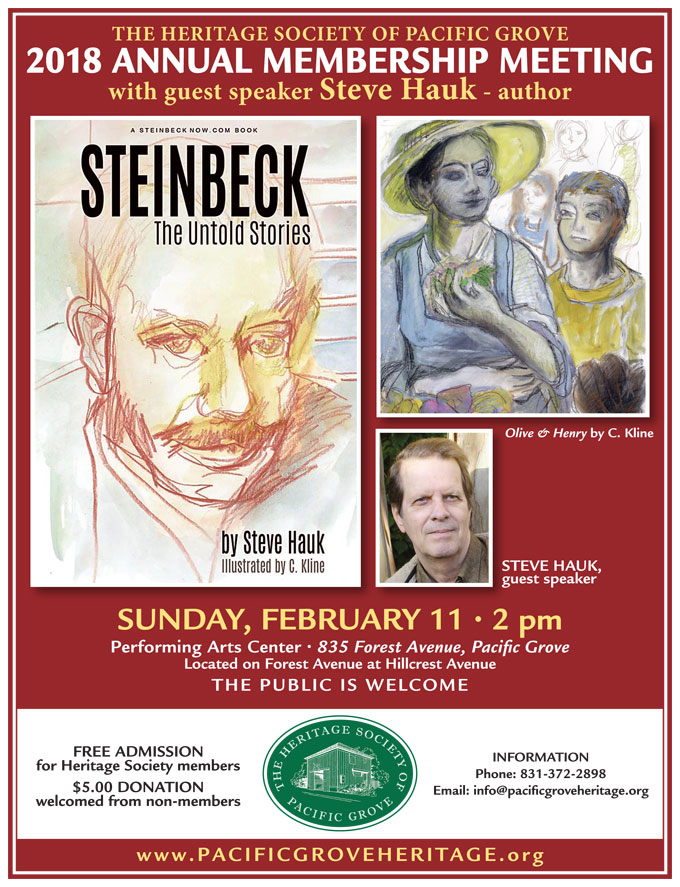

John Steinbeck Returns to Pacific Grove on February 11

The Pacific Grove Heritage Society is an appropriate host, and the Pacific Grove Performing Arts Center an appropriate venue, for Pacific Grove author and art expert Steve Hauk to talk about the writing of Steinbeck: The Untold Stories—a collection of 16 short stories inspired by people, places, and incidents from the life of the Nobel Laureate who did much of his writing at the Pacific Grove cottage built by his family more than 100 years ago. Presenting Steve Hauk on John Steinbeck fits the mission of the Heritage Society, to raise public awareness of local history and architecture, and the purpose of the Performing Arts Center, built in 1923 to accommodate concerts and lectures—a popular pastime in Pacific Grove since its founding as a Chautauqua assembly ground in 1875. The annual meeting of the Heritage Society featuring Steve Hauk starts at 2:00 p.m., Sunday, February 11, and is open to the public. The Pacific Grove Performing Arts Center is located on the campus of Pacific Grove Middle School at 835 Forest Avenue. Street parking is free and donations are tax-deductible.

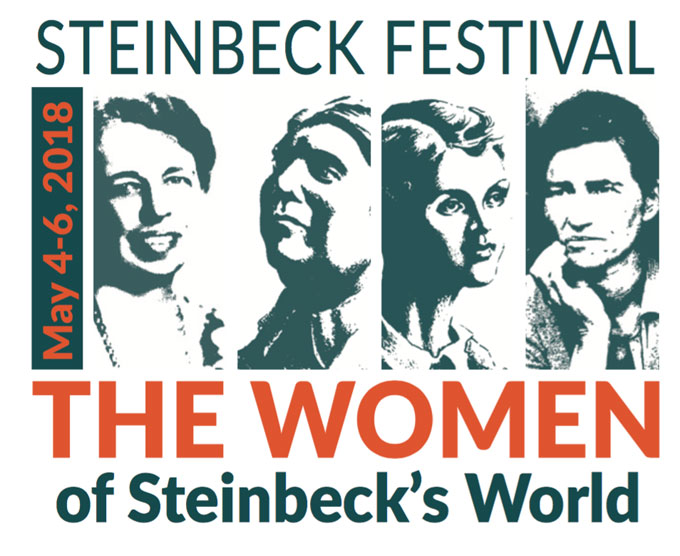

2018: Year of the Women in The World of John Steinbeck

Three sisters. Three wives. Three novels with female characters who are larger than life. Inspired by Ma Joad’s enduring example in The Grapes of Wrath, this year’s Steinbeck Festival will celebrate the women in John Steinbeck’s life and fiction over three days in May, at three venues associated with women Steinbeck cherished or invented. Sponsored by the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, the festival opens on Friday, May 4, and features an afternoon of seminars at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Center in Pacific Grove—where Steinbeck and his sister Mary studied biology as undergraduates—tours of the nearby “Doc” Ricketts lab where female visitors from Dora Flood’s place were always welcome in Cannery Row, and a full day of speeches and fun in the town where Steinbeck was a born and grew up, a slightly spoiled only son, and Cathy runs her brothel in East of Eden, without Dora’s kindness, Ma Joad’s goodness, or the nurturing instinct of Steinbeck’s mother, sisters, and wives (save one). Speakers include Richard Astro, the author of John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts; Mimi Gladstein, an expert on women in American fiction and the author of a study of Steinbeck’s female characters with the intriguing title “Maiden, Mother Crone”; and Susan Shillinglaw, director of the National Steinbeck Center and author of Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage. A full schedule of events and information about tickets and logistics can be found on the National Steinbeck Center’s festival page.

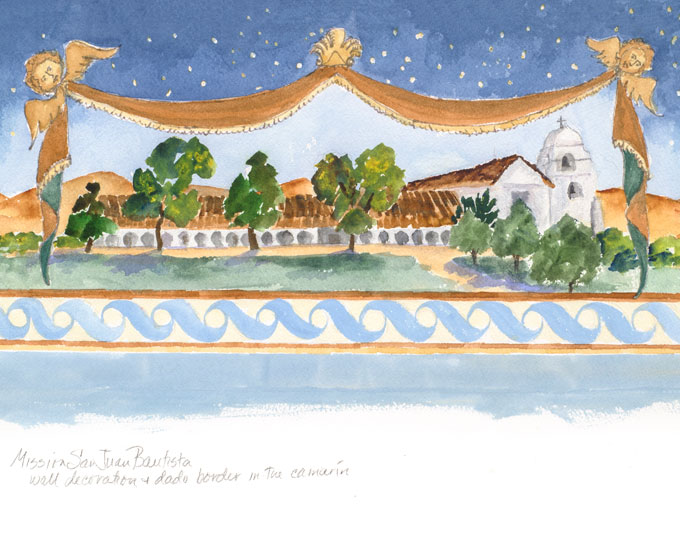

Mission Art by Nancy Hauk Mirrors Steinbeck’s History

An exhibition of art in the California mission town of San Juan Bautista by the late Nancy Hauk, whose home in Pacific Grove was once the residence of the man Steinbeck mythologized as “Doc,” will have special meaning for readers curious about the history behind Steinbeck’s California fiction. Thirty years before Steinbeck was born to the west, in Salinas, voters in eastern Monterey County, including the Mexican Californians of San Juan Bautista and Yankee settlers in Hollister, were promised their own county if Salinas became the seat of Monterey County instead of Monterey, the mission town that was California’s first capital. One outcome of this political decision was the emotional geography that came to define Steinbeck’s social sympathies and sense of place. Salinas boomed, Monterey languished, and in 1874 the County of San Benito was born, named for the river the Spanish called after St. Benedict when they built the mission they named for John the Baptist. Hollister, the nearby town where Steinbeck’s father’s family farmed and raised five sons, became San Benito’s county seat.

Steinbeck’s mother’s family lived in Salinas before the county split, and she returned to live there with her husband in 1900. He became Monterey County treasurer following a political scandal. She became the kind of local activist who took sides on civic issues like the vote of 1874. Their son’s feelings about Salinas ran in the opposite direction and eventually became material for his writing. The family’s cottage in Pacific Grove was a refuge from Salinas when Steinbeck needed one, and the Hauk house where “Doc” Ricketts once lived is nearby. So is the Monterey lab that attracted artists, misfits, and other characters celebrated by Steinbeck in his Cannery Row fiction. The conflict between Salinas and Monterey epitomized in the San Benito vote 50 years earlier was emblematic of a deeper division explored in East of Eden, the book Steinbeck wrote for his sons. Steinbeck’s art reflected his sympathies in this fight and caused controversy. Nancy Hauk’s art reminds us of the history behind the fiction.

Steinbeck’s mother’s family lived in Salinas before the county split, and she returned to live there with her husband in 1900. He became Monterey County treasurer following a political scandal. She became the kind of local activist who took sides on civic issues like the vote of 1874. Their son’s feelings about Salinas ran in the opposite direction and eventually became material for his writing. The family’s cottage in Pacific Grove was a refuge from Salinas when Steinbeck needed one, and the Hauk house where “Doc” Ricketts once lived is nearby. So is the Monterey lab that attracted artists, misfits, and other characters celebrated by Steinbeck in his Cannery Row fiction. The conflict between Salinas and Monterey epitomized in the San Benito vote 50 years earlier was emblematic of a deeper division explored in East of Eden, the book Steinbeck wrote for his sons. Steinbeck’s art reflected his sympathies in this fight and caused controversy. Nancy Hauk’s art reminds us of the history behind the fiction.

“Paintings of the California Missions,” an exhibition of work by Nancy Hauk (in photo), includes the Mission San Juan Bautista image shown here. The show has been extended and will run through May 2018.

December 7 Event Features Steinbeck Program Fellows

Three 2017-2018 fellows from the professional creative writing program funded by the founder of the John Steinbeck center at San Jose State University will read from their work and answer audience questions at 7:00 p.m. on December 7, 2017, in Room 590 of the MLK Library on the SJSU campus in downtown San Jose, California. Martha Heasley Cox, the professor-philanthropist who advanced the study and teaching of John Steinbeck by example and exhortation when she was alive, left a large estate gift ensuring the financial security of the program, which supports a select group of writers each year, when she died in 2015. Sunisa Manning will read from the novel she is writing about a group of radicalized students in Thailand during the turbulent 1970s. Dominica Phetteplace will also read from her recent writing, which includes literary and science fiction. C. Kevin Smith, the third fellow who will share insights into his work, is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the grandfather of graduate creative programs in America. The San Jose State University event is free and open to the public and includes a reception. For further information, contact Nick Taylor, the writer-professor who directs the Steinbeck studies center and the creative writing program that comprise Cox’s extraordinary legacy, at nicholas.taylor@sjsu.edu.

The Forgotten Anti-Rebel Yell In Steinbeck’s Wayward Bus

Monterey County’s move to rename Confederate Corners, the isolated intersection south of Salinas, California restyled as Rebel Corners in The Wayward Bus, has renewed interest in John Steinbeck’s 1947 re-imagining of Plato’s Ship of Fools allegory, from Book VI of The Republic. Located on Highway 68 in unincorporated Monterey County, Confederate Corners got its name during the Civil War, when a handful of Southern sympathizers proposed seceding from California as a mark of solidarity with the Confederate States of America. Except for informed readers of The Wayward Bus, the Monterey County ranchers’ mini-rebellion was largely forgotten until controversy over the removal of racist flags and statues in several states of the former Confederacy erupted, post-Charlottesville, into Trumpian rhetoric around issues of ethnicity, immigration, and loyalty to the flag. Like the Ship of Fools metaphor embedded in Steinbeck’s neglected novel—which few critics recognized, then or now—the recent news from Monterey County is replete with the kind of irony that appealed to the author, a big-tent American who began writing The Wayward Bus in and about Mexico.

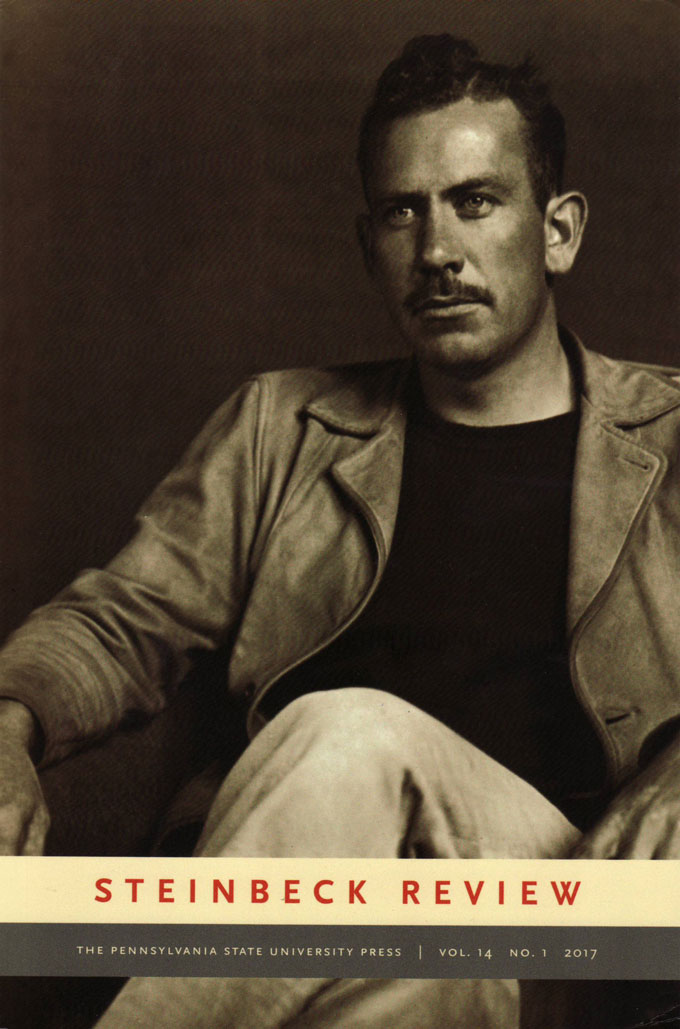

Steinbeck Review Expands Scope, Issues Call for Papers

Steinbeck Review, recently honored by listing in the international database Scopus, has expanded its purpose to specify that articles submitted for publication not only delight and instruct (à la Horace), but also illuminate issues, including the themes and problems treated in John Steinbeck’s work. This policy change reflects Steinbeck’s concern for truth and enlightenment, as well as for compassion and magnanimity, in books that warned readers of moral decline—and potential demise—in the America that Steinbeck loved. The subject of America and Americans preoccupied the writing of his final decade, and The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel, acknowledged this didactic purpose: “Readers seeking to identify the fictional people and places here described would do better to inspect their own communities and search their own hearts, for this book is about a large part of America today.”

How to Submit Papers for the Spring 2018 Issue

In addition to more traditional scholarly articles, Steinbeck Review invites the submission of papers for the Spring 2018 issue that reflect John Steinbeck’s continued relevance for our time. All critical and theoretical approaches are welcome, as are essays focused on women’s and gender studies, rhetorical concerns, ecology and the environment, international appeal, and comparative studies. Poetry submitted for publication should deal with themes or places associated with Steinbeck’s life and work. Submit papers before January 15, 2018 through the journal’s automated online submission and peer review system at the Pennsylvania State University Press.

The Passing of Frank Wright And the Men’s Clubs of John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row

The recent death of Monterey, California businessman Frank Wright at age 98 served as a reminder that the life of Doc’s Lab—Ed Ricketts’s marine biology laboratory on Cannery Row—had two distinct phases. The 1930s and 1940s were the period of John Steinbeck and Ricketts and the artists and poets and philosophers who gathered around them. The 1950s began the Lab’s second incarnation as a men’s club of painters, cartoonists, teachers, journalists, lawyers, and business people founded by Frank and his friends—all with a passionate interest in Steinbeck and Ricketts and a way of life that was already fading into the past. Like the earlier, even more casual men’s club, Frank’s group met and socialized and partied in the Lab’s raffish rooms and outdoor concrete deck and holding tanks overlooking Monterey Bay. In the process they kept the Lab largely as it was, preserving it for posterity.

The Men’s Club That Saved Doc’s Lab

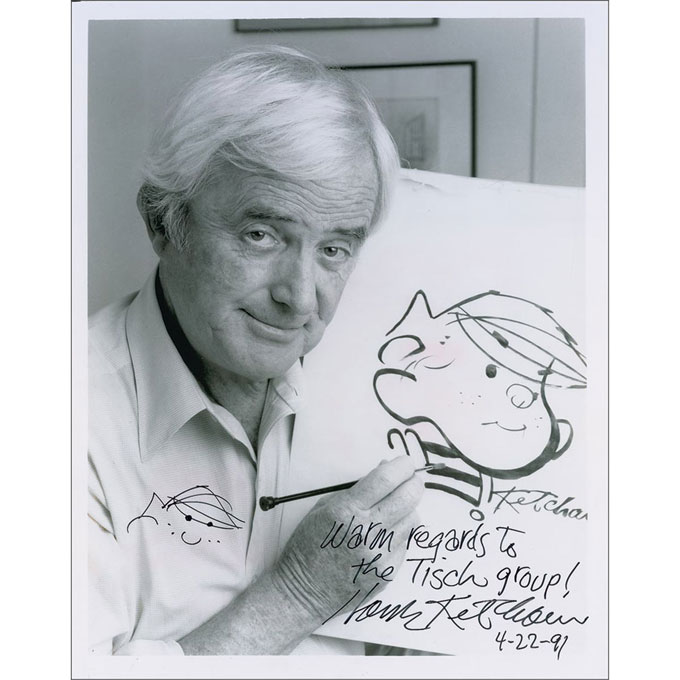

Frank met Ricketts after joining the Army in 1942, and they remained close until Ed died. In the early 1950s, Frank and two other men bought the Lab as a meeting place for their circle of artists, educators, and fellow enthusiasts. For a slim sampling of this second generation Cannery Row men’s club, there was Gus Arriola, the brilliant creator of the comic strip Gordo. Eldon Dedini, the farm boy from South Monterey County who became a successful and sophisticated cartoonist for Esquire and Playboy. Morgan Stock, the teacher and director who spearheaded the drama department at Monterey Peninsula College, which in turn named a theater for him. The irrepressible, crusading attorney Bill Stewart. The Dennis the Menace cartoon creator Hank Ketcham (in photo), also a serious painter. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts, they were creative types drawn together by a love of talk, drink, and music. The Monterey Jazz Festival grew from their collaboration. So did the idea of making Doc’s Lab a living museum, now under management by Monterey, California’s department of cultural affairs.

The End of an Era on Cannery Row

A personal memory: Years ago my late wife Nancy and I were walking along Cannery Row with Sue and E.J. Eckert (in photo to Nancy’s right). When we stopped in front of the Lab we got lucky. Frank Wright was standing on the stairs with Dennis Copeland, cultural affairs director for Monterey, California. Frank offered to give us a tour. He was a natural storyteller, warm and personable and charming, and when we left, walking out onto the bright morning sunlight of Cannery Row, the Eckerts said, “Boy, that was something!” They’ve never forgotten the experience. It was Frank’s gift to many when he was alive, and he was active well into his 90s. His death was indeed the end of an era.

Photo of Frank Wright courtesy Monterey County Weekly.

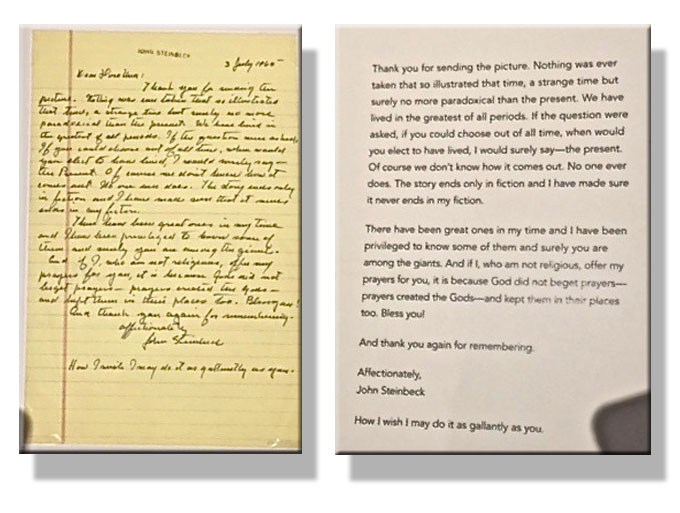

Bless You! John Steinbeck’s Letter to Dorothea Lange

Shortly before the show closed on August 27, my wife and I drove from our home in Salinas to the Oakland Museum of California to see Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, an exhibit devoted to the documentary photographer whose images of the 1930s quickly became associated with John Steinbeck and The Grapes of Wrath. Like Steinbeck’s novel, Lange’s Great Depression pictures have become symbols of the suffering of farmland Americans displaced by joblessness, drought, and despair. Less familiar but equally powerful are the events recorded in Lange’s photos of Japanese-Americans “relocated” from their homes to internment camps after Pearl Harbor—an executive order signed by President Roosevelt that Steinbeck and Lange both questioned at the time. Lange’s internment images were so evocative, and so damning, that most of them were confiscated by the government and suppressed, even after the war. Also on display was the letter John Steinbeck wrote to Dorothea Lange on July 3, 1960, looking back on their friendship and the events of the Great Depression and ending with this deeply personal statement, half-confession and half-benediction: “And if I, who am not religious, offer my prayers for you, it is because God did not beget prayers—prayers created the Gods—and kept them in their places too. Bless you!”

In 2017 the Iran Deal Included John Steinbeck’s Hometown

Guest book entries by visitors to the gift shop in the basement of John Steinbeck’s childhood home show that the Steinbeck House remains popular with readers who travel to Salinas, California from other towns, states, and countries. For example the guest book page for July 17-August 17 contains entries from a cosmopolitan array, including France, Wales, the Netherlands, Hungary, Norway, New Zealand, Germany, England, Italy, and Canada. Less conventionally, guest book entries for the current year also include the Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Portugal, Iceland, South Africa, and—even more surprising—the Republic of Iran. An internationalist who believed that good treaties prevent bad outcomes, John Steinbeck would like the idea that the Iran deal with the United States extended, however briefly, to Salinas, California.