Adult education programs at community colleges throughout America aim to serve local interests, and Monterey Peninsula College is no exception. The main campus of the two-year institution—founded in 1947 as part of the California Community Colleges system—is a familiar feature of the pleasing approach to Monterey and Pacific Grove from U.S. Highway 1. John Steinbeck did much of his writing in and about the area, so it’s no surprise that creative writing, creative writers, and Steinbeck’s life play a bigger role at Monterey Peninsula College than on most campuses of similar size. The latest example of this preoccupation is the adult education series Gentrain (for General Education Train of Courses), where Steve Hauk will discuss Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, short stories about Steinbeck’s life, from 1:30 to 2:30 p.m. on Wednesday, September 5, in Lecture Forum 103 at Monterey Peninsula College. Lisa Ledin, the weekend host for KAZU-FM radio, will read from the collection. Admission is free. Campus parking is $3.

Vote Early and Vote Often for The Grapes of Wrath in 2018

The Grapes of Wrath, the book John Steinbeck finished writing in time to vote for Culbert Olson as Governor of California in 1938, is still running strong with readers, despite naysayers like the Los Gatos Republican who wrote a counter-novel, now forgotten, in 1940. This year The Grapes of Wrath has competition in the race for Great American Read—a project of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with support from the Anne Ray Foundation, to encourage reading by allowing anyone over 12 to vote early and vote often for his or her favorite from a list of 100 novels, all in English, that polled well with viewers. The contest would probably appall Steinbeck, a one-man, one-vote Democrat who thought popularity pageants were stupid, especially where writers were concerned. Among the books we know he read was Two Years Before the Mast, a seagoing Grapes of Wrath written in 1840 by Richard Henry Dana, the Massachusetts lawyer and reformer who coined the phrase “vote early and vote often” in a letter about election rigging in his day. Great American Read rules permit repeat voting by the same person and reward social networking to spread the word about books, 21st-century style. So get with the program. Vote early and vote often for The Grapes of Wrath.

Trump Relief: Bill Hader’s Riff on Of Mice and Men

It’s a shame John Steinbeck didn’t live to see Saturday Night Live. The author of Of Mice and Men died in December 1968, six weeks after Richard Nixon was elected President; SNL debuted in 1975, fourteen months after Nixon resigned in disgrace. Much about Nixon’s America depressed Steinbeck, including Nixon’s party, but he kept his sense of humor and he understood the medium of television, Nixon’s undoing against Kennedy in 1960. If Steinbeck had lived longer he might have enjoyed SNL’s blend of comic relief and left-leaning satire, given his preference for politicians like Kennedy and Stevenson, the witty Democrat from Illinois defeated by Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956. Steinbeck critiqued Eisenhower’s thought (conventional), syntax (chaotic), and reading (cowboy fiction), so it’s easy to predict his reaction today to a worse-than-Eisenhower type like Donald Trump, or Rick Perry—brilliantly impersonated by Bill Hader, riffing on Of Mice and Men in this SNL sketch about the 2012 Republican candidate debate at which the man Trump made Secretary of Energy couldn’t remember the name of the federal department he now heads. If you need comic relief from Trump-induced depression, watch Bill Hader’s Rick Perry channel Lennie, with Mitt Romney as George at his side. Imagine John Steinbeck at your side and you’ll both die laughing.

Test Drive John Steinbeck’s America and Leave Feedback

Early in 1938, as Steinbeck began writing The Grapes of Wrath at his home in the mountains, he was nervous about doing justice to an American tragedy unfolding in real time: the flight of desperate farm families from the Dust Bowl states of Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas to the Promised Land of California. “I’m trying to write history while it is happening,” he explained in a letter to his agent Elizabeth Otis, “and I don’t want to be wrong.” In the spring semester of 2017 I taught a course on John Steinbeck’s America that showed how right he was. It resulted in a new author website devoted to the world that John Steinbeck critiqued and created.

Twenty-three upperclassmen and two graduate students (one from Poland) enrolled for the course, offered in the University of Oklahoma’s College of Arts and Sciences. They came from Biology and Psychology and Letters as well as English and History, the departments in which it was cross-listed for credit. They read a variety of John Steinbeck’s works and discussed them within the context of American history and current events. They wrote papers on Steinbeck’s travels and wartime writing, works on stage and screen, Oklahoma, and East of Eden. They created the website introduced here for the first time for your comment.

The effort had excellent support. Mette Flynt, a PhD candidate in History, helped tighten prose, ensure accuracy in citations, and achieve consistency of language and layout. Paul Vieth, an MA student in History of Science, assisted with the Resources and Research page. Sarah Clayton—the University of Oklahoma Libraries staff member who won a national award for her innovative work with digital humanities course initiatives like this one—provided the class training in website construction using Omega, an open-source publishing platform. You can help by test driving the site and making suggestions.

Go to John Steinbeck’s America and give us your feedback in the comment box below.

May 1-3, 2019 Conference to Celebrate Steinbeck Now

In observance of the anniversary of John Steinbeck’s death on December 20, 1968, the International Society of Steinbeck Scholars invites proposals for papers exploring Steinbeck’s continued relevance, 50 years later, to be delivered at the organization’s May 1-3, 2019 conference at San Jose State University. “Steinbeck and the 21st Century: Identity, Influence, and Impact” is sponsored by the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies and will take place at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library in downtown San Jose, California. According to Nick Taylor, the center’s director, proposals for papers are welcome from a wide variety of disciplines, including literary and cultural studies as well as ecology and pedagogy, and may encompass the comparative examination of Steinbeck and 21st century authors, issues surrounding the reception and translation of Steinbeck’s books in the 20th century, and commentary on Steinbeck’s writing from the perspective of movements like #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and organized resistance to the mistreatment of migrants and refugees in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East. Also of interest is how classroom teachers today use Steinbeck to engage students on social issues, popular culture, and artistic expression. Travel funding is available for students whose papers are accepted. For details visit the conference web page.

As of today’s post we are temporarily suspending weekly posts at SteinbeckNow.com to pursue a print project requiring attention. We will continue to respond to email inquiries, curate comments, and post news about opportunities like this one, and we will review guest-author submissions in the order they are received when we resume weekly publication. Thank you for your understanding and cooperation.—Ed.

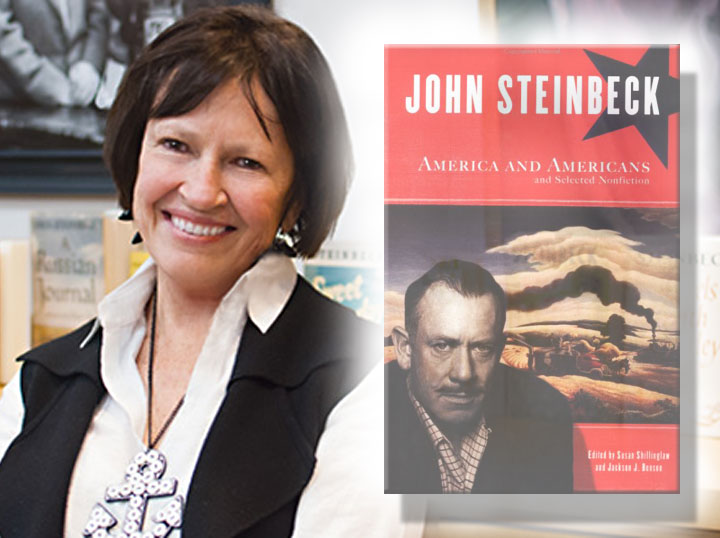

Susan Shillinglaw Leaving National Steinbeck Center

Susan Shillinglaw, a leading figure in Steinbeck studies for three decades, has resigned as Director of the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, effective June 15. The Pacific Grove resident and San Jose State University English professor took over management of the organization three years ago, guiding the transition to a new landlord and reviving the annual Steinbeck Festival, an anticipated event in Steinbeck’s home town since 1981. Built on Main Street in downtown Salinas, the center contains an archival collection and space for exhibitions, meetings, and educational programs.

The author or editor of numerous books and articles—and an internationally acclaimed speaker known for style and substance—Susan Shillinglaw has co-directed six National Endowment for the Humanities interdisciplinary summer institutes for high school teachers in Pacific Grove, including one this summer. For 18 years she directed the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State, where she began her teaching career in 1984. She transitioned to half-time faculty status when she accepted the position in Salinas, and she will teach courses in Steinbeck and creative nonfiction in the fall.

Since opening its doors 20 years ago, the National Steinbeck Center has had to overcome challenges of staff turnover and financial troubles typical of small, non-urban museums burdened with start-up debt and dependent on local philanthropy and tourism for survival. The building was sold to California State University, Monterey Bay as a partial solution to the problem, but museums in this era must also offer new kinds of programs and shift the ways exhibits are structured—activities begun in earnest under Susan Shillinglaw’s leadership.

John Steinbeck’s Women in Sag Harbor and Salinas

The village setting of The Winter of Our Discontent closely resembles Sag Harbor, the Long Island town where John Steinbeck liked to loaf and write, and the women in The Winter of Our Discontent reflect aspects of the women in Steinbeck’s personal life, the focus of the 2018 Steinbeck Festival in Salinas, the California town where the author of The Winter of Our Discontent grew up with a sister named Mary and a girl from church who went on to marry a man named Hawley. Susan Shillinglaw wrote the introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of The Winter of Our Discontent and conceived of the idea for this year’s Steinbeck festival, so there’s a pleasant symmetry to the May 18-20 celebration of the novel being planned in Sag Harbor, where Shillinglaw (in photo) will lead public discussion and the book will be read aloud, cover to cover, at Canio’s Cultural Café. Salinas and Sag Harbor were bookends in the life of John Steinbeck. So were the trio of Marys from Steinbeck’s family and the family of the novel’s hero Ethan Hawley—Steinbeck’s beloved sister; Ethan’s steadfast spouse, and the enlightened daughter who prevents his discontent from becoming despair. The temptress in Ethan Hawley’s tale also has a correlative in Steinbeck’s personal history. To find out who she was, sign up for the May 4-6 celebration of The Women of Steinbeck’s World and note whose name is missing from the honor roll. If Long Island is more convenient, show up for the May 18 talk by Susan Shillinglaw, the link between Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor and Salinas, and ask.

Art of the River That Runs Through Steinbeck’s World

John Steinbeck’s love affairs with women, the fine arts, and the Salinas River valley come together at the 2018 Steinbeck Festival in Salinas, California when the artist and writer Janet Whitchurch talks about Underground and Running North, a new fine art book featuring her images and text. Sponsored by the National Steinbeck Center, “The Women of Steinbeck’s World” runs Friday, May 4 through Sunday, May 6 in Salinas, Monterey, and Pacific Grove and includes daytime lectures and tours, after-hour social events, and an art-feature talk by Whitchurch about the local river that inspired her book—and, like the women in his world, both inspired and frightened John Steinbeck, whose lifelong love affair with fine art and writing was fortunately less ambivalent. Don’t miss out on the variety and fun. Purchase your ticket today.

Not John Steinbeck’s View

Purple sofas, 4,000 square feet, and an elevated view of midtown may make the New York apartment where John Steinbeck died in 1968 a bargain at $5 million, as asserted in the sale listing for 190 East 72nd Street, but the stark contrast with Steinbeck’s unvarnished view of the world in 1938 will not have escaped thoughtful readers of The Grapes of Wrath. A house is not a home if you’d rather be somewhere else, and Steinbeck preferred the little getaway he and his wife Elaine bought way out on Long Island because he preferred small towns, small houses, and doing his writing without a distracting view, however elevated. When Elaine Steinbeck died, new owners doubled the space of the apartment and added bedrooms and bathrooms (six of each) but kept the roll-top desk used by Steinbeck and offered as part of the sales pitch. But a sales picture is worth a thousand words. Compare the hard lines and assertive scale of the souped-up, for-sale living room, with its massive, grape-purple sofas and $5-million view, and the solitary appeal of the modest house where Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath—an unvarnished depiction of the stark contrast, then and now, between people with no home and those who live in glass houses but insist on throwing stones.

Photo of John Steinbeck’s Santa Cruz mountain home courtesy Los Gatos Public Library

Picturing Edgar Allan Poe

As I was planning a trip from Virginia to California to visit my family in late February, I decided to add a two-day excursion to Salinas and the Steinbeck National Center. Shortly before I left, my eye was caught by a poetic tribute to Edgar Allan Poe at Steinbeck Now.com, an author website that had only recently come to my attention. Poe initially sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Now John Steinbeck has reignited my torch.

As I was planning a trip from Virginia to California to visit my family in late February, I decided to add a two-day excursion to Salinas and the Steinbeck National Center. Shortly before I left, my eye was caught by a poetic tribute to Edgar Allan Poe at Steinbeck Now.com, an author website that had only recently come to my attention. Poe initially sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Now John Steinbeck has reignited my torch.

Poe sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Steinbeck reignited my torch.

At my website LitChatte.com I have identified Poe as the first of a line of great American literary writers who portray American history imaginatively. While acknowledging that John Steinbeck continued the tradition, I was surprised to find a poem about Poe on an author website devoted to a writer best known for fiction. Though I can’t say that Roy Bentley’s poem is a fair portrayal of Poe—a pioneer who contributed to the advancement of American literature and the vocation of John Steinbeck—reading it reminded me that both writers were trashed by misinformed critics when their works first appeared and again when they died. Steinbeck was called a communist and a liar and his characters were deemed two-dimensional when The Grapes of Wrath was published. At the National Steinbeck Center I learned that copies were burned in Salinas and banned from schools and libraries around America, despite Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize.

I was surprised to find a poem about Poe on an author website devoted to a writer best known for fiction.

Similarly, Poe’s character and work were maligned by critics in his day, most harshly by Rufus Griswold—a contemporary who served as one of Poe’s principal editors—in The Poets and Poetry of America, an anthology edited by Griswold, and in an unsympathetic obituary of Poe that Griswold wrote under a pseudonym. The existing tension between the two men was exacerbated when Poe took exception to Griswold’s inclusion and omission of certain poets after the anthology appeared in 1842. Griswold retaliated by trashing Poe’s personal life in the October 9, 1849 New York Daily Tribune obituary he signed “Ludwig.”

Like Steinbeck, Poe’s character and work were maligned by critics in his day, most harshly by Rufus Griswold.

It didn’t take much detective work to determine that “Ludwig” was Griswold, a conniver who gained a stranglehold on future publication of Poe’s work (by usurping the role of Poe’s literary executor from Poe’s living relatives) and who damaged Poe’s reputation by falsely claiming that he “had few friends.” Halfheartedly conceding that “literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars,” Griswold’s obituary portrayed Poe as a vagabond who moved pointlessly between Baltimore, Richmond, New York, and Philadelphia, even though Griswold worked at different times in the same cities—the only literary centers where a struggling writer (or editor) could hope to make a living in the first half of the 19th century.

Griswold’s obituary portrayed Poe as a vagabond who moved pointlessly between the only literary centers where a struggling writer could hope to make a living.

With each move, Poe developed an essential pillar of his versatile career as a professional writer, one which became a vocational model for later authors, like Steinbeck and Twain, who used their journalism to inform and inspire their literary creations. Griswold’s “Ludwig” obituary also spread the myth that Poe was a hopeless alcoholic and a madman, and it predicted that neither he or his writing would be long remembered. Time has disproved Griswold’s prophecy, and Griswold’s claims about Poe’s character and behavior have been discredited by serious scholars, though unwitting writers continue to base their assumptions about Poe on Griswold’s intentional misdirection.

With each move, Poe developed an essential pillar of his versatile career as a professional writer who used journalism to inform literary creation.

Reliable information can be found at the author website founded by the Poe Society, which points the reader to The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, by Dwight Thomas and David Jackson. A comprehensive account of Poe’s professional and personal activities, it documents Poe’s friendships, and the position of respect he held in social circles where he was known. Though Poe wrote masterpieces of horror, he wasn’t mad, and the state of inebriation noted by others may well have been caused by acute sensitivity to alcohol, small amounts of which made him sick and appear drunk. Poe’s drinking was limited to social situations where gentlemen were expected to imbibe. A disciplined writer (there are no credible accounts of drinking while writing), Poe was devoted to his young wife Virginia, whose death a few years before his own contributed to his emotional and physical deterioration.

Though Poe wrote masterpieces of horror, he wasn’t mad, and the state of inebriation noted by others may have been caused by acute sensitivity to alcohol.

The true picture of Poe’s life explains why the poem at SteinbeckNow.com concerned me. It opens by suggesting that Poe could or would have downed “thirteen insipid whiskeys,” a preposterous proposition, despite the clever pun on “insipid.” (From what we know about his clinical condition, it’s likely he would become disoriented after the first drink and pass out after the second.) The elusive line “A joke is to say what its poets are to America” reflects a viewpoint advanced by Griswold in his anthology, and the reference to Poe’s strained relationship with his “foster father” John Allan, who “left him nothing,” repeats a misconception about Poe’s later behavior. Having dropped Allan’s name, he worked hard to provide for himself and his wife. He was prolific and his work sold well abroad. But lax copyright laws failed to protect writers’ interests in 19th century America, and Poe suffered the consequences.

Poe was prolific and his work sold well abroad. But lax copyright laws failed to protect writers’ interests in 19th century America, and Poe suffered the consequences.

Mark Twain learned from Poe’s experience and eventually self-published. Copyright laws improved in the 20th century, and writers like John Steinbeck (who also had a more supportive father) lived to achieve the financial security denied to Poe. Roy Bentley’s poem may have been intended as a tribute, but it fails to reflect the facts of Poe’s life, or Poe’s contribution to the progress of American literature. Instead of shedding new light on a sympathetic subject, it continues the slight to Poe’s reputation consciously created by Rufus Griswold, who knew that “a story will circulate” once it’s invented. Though eloquent, the last line of the poem (“If God exists, it isn’t to love poets”) regrettably reinforces that unfortunate conclusion.