“Revisiting the American Nazi Supporters of ‘A Night at the Garden’”—Margaret Talbot’s political think piece in this week’s New Yorker—raised the intriguing question posed by Robert DeMott in an email to Steinbeck fans today. Was John Steinbeck aware of the racist rally that attracted 20,000 Hitler fans to Madison Square Garden, the midtown Manhattan building where he’d once done grunt work, on February 20, 1939? Even in California, it’s hard to imagine he wasn’t, despite being otherwise engaged at the time worrying about his novel The Grapes of Wrath, which came out two months later. World War I had sensitized Americans with German names like Steinbeck to issues of loyalty and ethnicity, and anti-New Deal attacks on The Grapes of Wrath included criticism from Americans convinced that Steinbeck and Roosevelt were both Jewish names. Talbot says the Nazi movement in the United States was saved from itself by Pearl Harbor, and that raises another intriguing question for Grapes of Wrath fans. Without the jobs or moral clarity created by World War II, would folks like the Joads have sided with liberals like Steinbeck, or with the pro-Nazi crowd at Madison Square Garden in 1939? As this film of the event shows, it looked a lot like the kind of rally where Americans like the Joads are expressing their enthusiasm for Donald Trump in 2019.

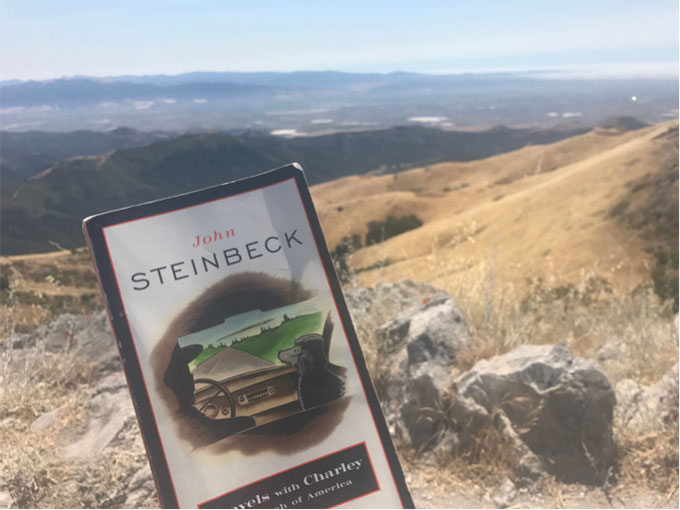

Photograph courtesy Marshall Curry / Field of Vision