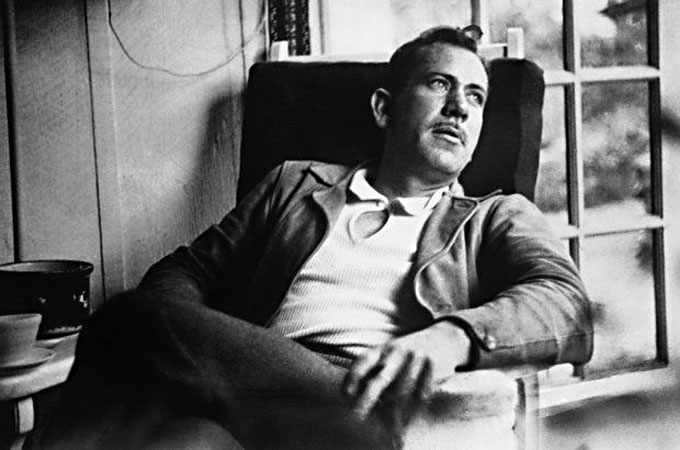

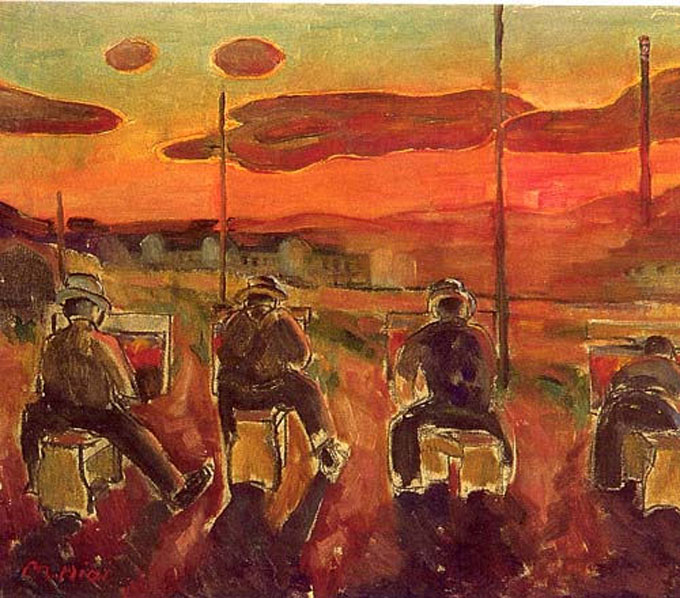

Cain and Abel. Charles and Adam. Cal and Aron. The actor Emilio Estevez and his brother, the actor Charlie Sheen, have the kind of sibling rivalry that John Steinbeck rendered as a curse and an example in East of Eden. So it’s fitting that Emilio Estevez—the Abel in the Sheen family picture—drew inspiration from The Grapes of Wrath when he wrote and directed The Public, the socially conscious feature film in which he also performs, along with Christian Slater, Jena Malone, and Alec Baldwin, another actor with a brother who can be difficult. Set in Cincinnati and released in time for the gala opening of the Santa Barbara Film Festival last week, The Public is about a group of homeless patrons who refuse to leave the library when a cold front fills emergency shelters and makes returning to the streets a deadly proposition. An appreciative review of the movie at Edhat Santa Barbara notes that The Grapes of Wrath “figures prominently as a thematic and quotation reference” and that “the library in itself becomes a character—it disperses information, yet also is full of great works of literature that [ask] us to ponder life, morality, and meaning.” Like food and shelter, keeping the public in public library is a life-and-death matter for such book-minded observers of events as Emilio Estevez—Abel-types who view policemen beating up protestors in cities like Cincinnati as the spiritual sons of Cain-types from places like Salinas and Bakersfield, the bullies with badges who brutalized migrants living in boxes on the outskirts of town and burned The Grapes of Wrath in front of the library when John Steinbeck protested their actions in his greatest book.