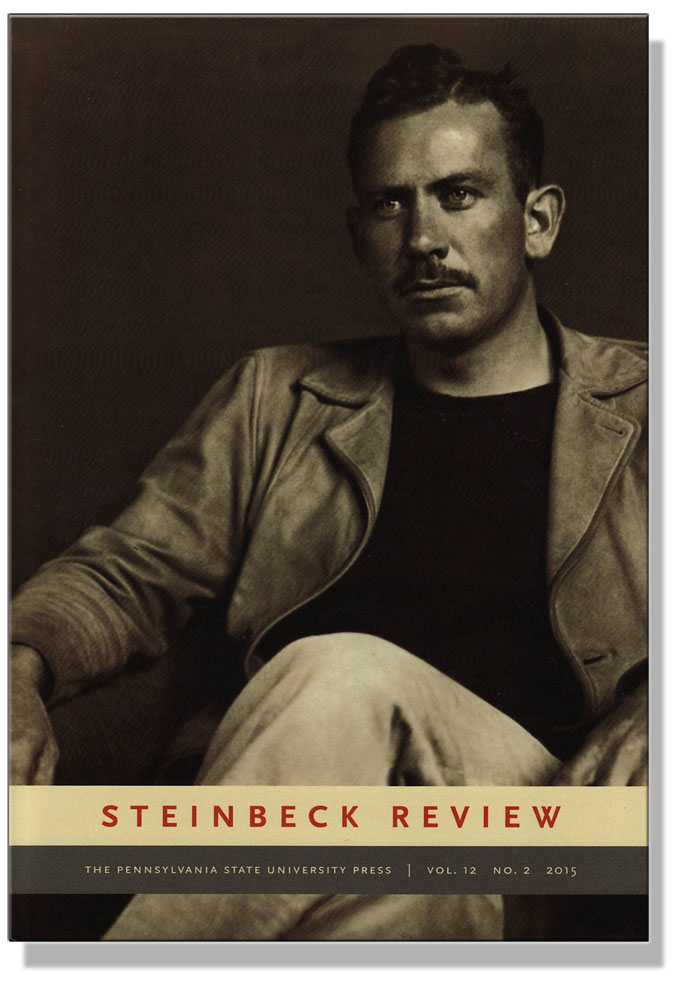

Who said literary criticism is just for critics? Not the editors of Steinbeck Review. The winter 2015 issue proves that San Jose State University, the journal’s publisher, embraces diversity in many forms, and that its editors are willing to let non-critics play the specialist’s game. Among the current contributors are (1) a graduate student in history from Canada, (2) a former college film teacher, (3) a retired biology professor and dean living in Oregon, (4) a Steinbeck fan from California’s Central Valley, and (5) the W.W. Kellogg Professor of Agriculture, Food and Community Ethics at Michigan State University. But the unlikeliest candidate in the intriguing mix may be Daniel Levin, a pharmaceutical research executive with a Ph.D. in chemistry from Cambridge University who now lives in California. Prompted by a visit to the National Steinbeck Center and curious about apparent discrepancies between an exhibit there and Steinbeck’s Hebrew in East of Eden, Levin took a scientific approach, consulting Talmudic sources, Steinbeck curators, and a Hebrew language adviser to investigate Steinbeck’s adaptation of the term timshol from the Genesis story about Cain’s banishment, east of Eden, after he kills his brother Abel. “John Steinbeck and the Missing Kamatz in East of Eden: How Steinbeck Found a Hebrew Word but Muddled Some Vowels,” the result of Levin’s exemplary study, demonstrates why, for lovers of John Steinbeck, literary criticism is too important to be left to professional literary critics. See for yourself. Subscribe to Steinbeck Review.

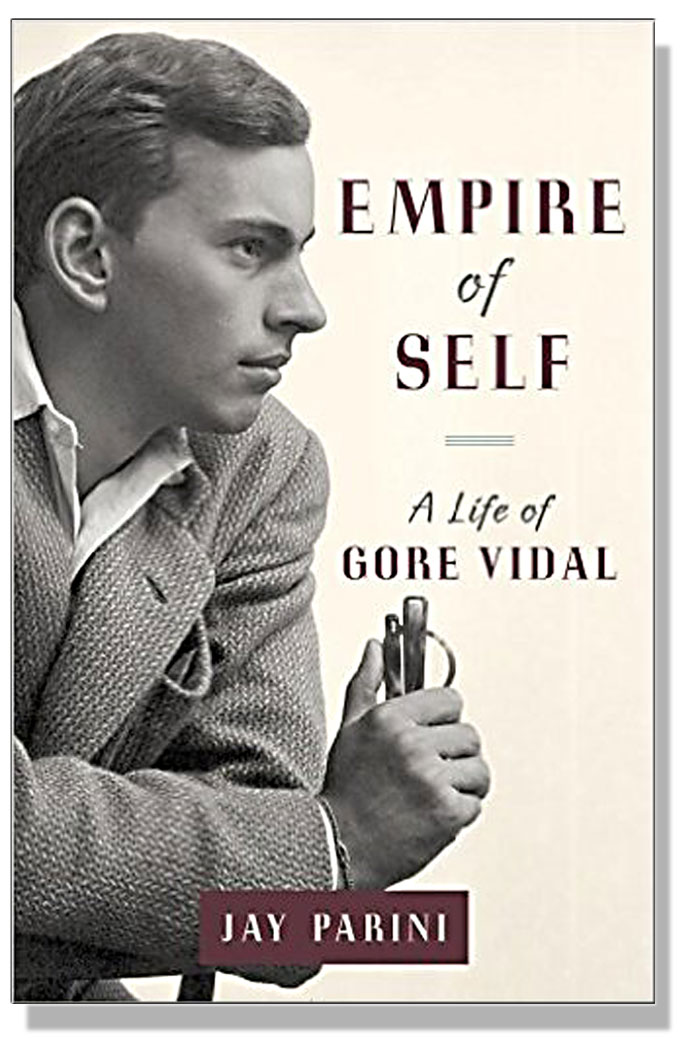

John Steinbeck Biographer Writes Life of Gore Vidal, Master of Historical Fiction

Though they were born a generation apart on opposite coasts, John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal—bestselling writers with close ties to Broadway, Hollywood, and progressive politics—had much in common. Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal, by John Steinbeck’s versatile biographer Jay Parini, considers the controversial author of Lincoln, Burr, and Myra Breckinridge to be a master of historical fiction, a literary form that didn’t fit Steinbeck but suited Vidal, who renewed its energy and spawned a generation of imitators. Axinn Professor of English at Middlebury College and a poet-novelist-critic who understands what creative writers endure for their craft, Parini suits Vidal particularly well as a biographer. Like John Steinbeck: A Life (1995), his life of Gore Vidal provides a contemporary writer’s perspective on a controversial literary career, with an advantage not shared by biographers of Steinbeck. Parini and Vidal were friends until Vidal’s death in 2012, and Parini had frequent conversations with his fascinating subject, who gave him free access to Vidal’s extraordinary circle of friends, associates, and yes, enemies.

Jay Parini, John Steinbeck, and the Case for Gore Vidal

The result of that fortunate relationship is a compelling chronicle—detailed in research, comprehensive in scope, and convincing in its case for Gore Vidal as a 20th century writer who, like John Steinbeck, is worth reading in the 21st. Describing himself as Vidal’s Boswell, Parini views his volatile subject with the empathy of a colleague and the wonder of a disciple, forgiving without judging, or ignoring, the master’s faults. This is an advisable stance for any biographer, but it serves Gore Vidal’s peculiar personality and expansive sense of self particularly well. John Steinbeck was a shy man with a domestic situation that made research and publication difficult for biographers following his death in 1968. Vidal, who admired Steinbeck and served as a source for Parini’s Steinbeck biography, avoided this danger by admonishing Parini to note the potholes but keep in his eye on the road when writing the biography that Vidal made Parini promise he would finish when Vidal was gone.

Parini views his subject with the empathy of a colleague and the wonder of a disciple, forgiving without judging, or ignoring, the master’s faults.

A gentle sort without Vidal’s sharp edges, Parini kept the bargain, filling in the self-narrative begun by Vidal in the novels Vidal wrote in his 20s, in essays and interviews and plays over a period of six decades, and in a pair of provocative memoirs that leave no prisoners. As suggested by the title Parini chose for his biography of this great-but-not-good man, Vidal’s story fascinates because it records the self-invention of a born storyteller who wrote prodigiously, characterized non-historical fiction like Myra Breckinridge as “inventions,” and considered bitchiness and versatility to be evidence of talent. He was as competitive with writers as we was in sex, and he fought publicly with colleagues who crossed or criticized him. He attacked Truman Capote, a soft enemy, and made scenes with Norman Mailer, a tougher target. He suggested that John Steinbeck, who avoided snits with other writers, was a bit of a one-note: “He “didn’t ‘invent’ things,” Vidal said of Steinbeck. “He ‘found’ them.”

Gore Vidal and John Steinbeck: Two Lives in Letters

Like Samuel Johnson, John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal were thin-skinned, temperamental men with mother issues. Both felt sorry for their fathers and identified with their fathers’ fathers, stronger figures, in their writing. Steinbeck compensated for self-doubt by avoiding public appearances and entangling private alliances beyond a loyal circle of friends, collaborators, and relatives. “Your only weapon,” he advised a young writer whose father was a boyhood friend, “is your work.” Vidal, a domineering narcissist, adopted the opposite strategy, creating a public persona built around conflict, desire, and adulation. Work was one weapon. So was a personality that, as Jay Parini observes, others could love or leave but never outrun. Steinbeck was a turtle. Vidal was a hare.

John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal were thin-skinned, temperamental men with mother issues. Steinbeck was a turtle. Vidal was a hare.

Reared in a rural California town where the Republican Party ruled and the Episcopal church was a center of social life, John Steinbeck got off to a slow start as a writer. Cup of Gold, his first novel, fails as historical fiction about a far-off time and place; an early attempt at mythic allegory, To a God Unknown, succeeds only because it is rooted in familiar soil. He finally found his voice in three novels, written during the Great Depression, about America’s rural underclass: ranch hands and farm workers in California, migrant sharecroppers from Oklahoma. He lived in small houses and wrote in small rooms and never forgot what it was like to go without; he feared success, and and he was right. A New Deal Democrat, he wrote political speeches but refused to make them. As with Gore Vidal, alcohol was a social lubricant, but to opposite effect. Vidal performed in company. Steinbeck looked and listened. Steinbeck liked working people, preferably farmers, and, like Faulkner, he lived part-time in the past. So did Vidal, of course, but his past was imagined rather than remembered.

Vidal performed in company. Steinbeck looked and listened. He liked working people, preferably farmers, and lived part-time in the past.

Vidal was born in Washington during the administration of Calvin Coolidge and spent his happiest times at the Rock Creek Park home of his blind grandfather T.P. Gore of Mississippi, elected U.S. Senator from Oklahoma when Oklahoma became a state. Vidal’s roots were Deep South (Al Gore is a distant relative), but his social centers as a boy were Capitol Hill, New York, and the mansions of his grandfather and his mother’s second husband, Hugh Auchincloss, a millionaire who later married the mother of Jackie Kennedy. Like Steinbeck, Vidal was christened as an Episcopalian, but he attended St. Albans, an exclusive academy run by the Episcopal Church, rather than public school. He fell in love with a classmate, and both enlisted at age 18. The boy he loved was killed in combat and, as Parini suggests, left a hole in Vidal’s heart that lasted for a lifetime.

Like Steinbeck, Vidal was christened as an Episcopalian, but he attended St. Albans, an exclusive academy run by the Episcopal Church, rather than public school.

He disliked his mother, liked his father’s girlfriends, and imbibed the Dixiecrat politics of his Grandfather Gore, which were to the right of the Steinbeck family’s progressive California Republicanism. Parini describes the anti-New Deal bias Senator Gore shared with Dixiecrat allies like Huey Long as “Tory populism”: anti-corporate, anti-war, and anti-statist, anti-values that defined Vidal’s vision of America as a Republic gone bad, like Rome, in his political essays, his historical fiction, and his campaigns for public office, first as candidate for Congress from New York, later for Governor of California. If Vidal read The Grapes of Wrath to Senator Gore as a teenager, a distinct possibility, the old man probably reacted like his fellow Oklahoman, Lyle Boren, who denounced Steinbeck’s depiction of Oklahoma from the floor of the U.S. House: with denial and disdain. Vidal’s view of America as a child was that of his grandfather’s political class: nativist, isolationist, and distrustful of Wilsonian-Rooseveltian democracy. His ambitions as an adult, like his homes on the Hudson and in Italy, were imperial.

Vidal’s view of America as a child was nativist, isolationist, and distrustful of democracy. His ambitions as an adult, like his homes on the Hudson and in Italy, were imperial.

Parini records the first time Steinbeck and Vidal met, on May 8, 1955, at a Manhattan party given by the producer Martin Manulis following the TV broadcast of Visit to a Small Planet, Vidal’s satirical comedy about Cold War paranoia and gone-mad McCarthyism. Vidal’s sci-fi caricature of mid-America invaded by aliens eventually ran on Broadway and has since been revived. When Vidal met Steinbeck at the Manulis party, Steinbeck would have been involved in staging Pipe Dream, the musical adaptation of Steinbeck’s novel Sweet Thursday by Rodgers and Hammerstein that closed within months after opening later in 1955. Steinbeck’s wife Elaine, also present at the party, was a stage manager for the 1940s hit musical Oklahoma! and had a good eye. She remembered the 30-year-old Vidal as “a tense, smart, glittering young man” who shared Steinbeck’s “passion for politics” and got along with her husband. The two men shared a special affection for Eleanor Roosevelt and an admiration for Adlai Stevenson, neither of which would have appealed to their families back home.

Steinbeck and Vidal shared a special affection for Eleanor Roosevelt and an admiration for Adlai Stevenson, neither of which would have appealed to their families back home.

Vidal also felt an affinity for Steinbeck as an artist, noting to Parini that both authors had the ability to write narrative and dramatic works that people liked. Vidal said he envied Steinbeck’s “happy relation to Hollywood,” where Steinbeck’s work “adapted well” and “was treated with respect,” unlike his own. He observed, accurately, that the film East of Eden “brought Steinbeck to more people’s attention than a novel could have ever done.” And though both writers feared that television “spelled the end of the novel,” their most popular works in novel form have also proved to be their most enduring: The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, Cannery Row, and East of Eden for Steinbeck; Burr, Lincoln, and other historical fiction of American Empire for Vidal. Of the book critics who were irritated by Steinbeck’s persistent popularity, Vidal observed, “they could never forgive Steinbeck for saying things that people wanted, or needed, to hear.” As Empire of Self shows, the same can be said of Gore Vidal.

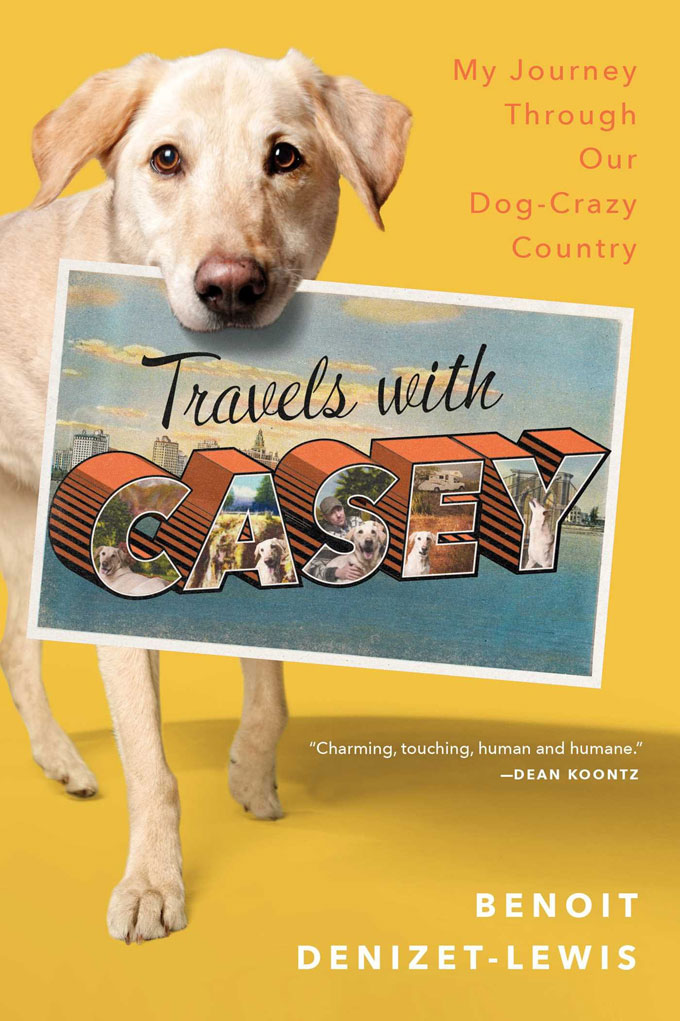

New York Times Writer Emulates John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley in a Book to Please Dog Lovers

John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley in Search of America inspired a recent book by a dog lover named Benoit Denizet-Lewis, a 39-year-old author from San Francisco who has been writing for the New York Times Magazine since he was 26. Travels with Casey, My Journey through Our Dog-Crazy Country is a whimsical account of connecting with contemporary America—half a century after John Steinbeck hit the road with Charley—accompanied by the book’s titular canine and by Rezzy, an abandoned puppy found along the way. The story is a dog lover’s delight, long on love but short on the uneven edges that lovers of literalism continue to expose in Travels with Charley.

Writing for Dog Lovers, Not John Steinbeck Fans or Critics

Other writers have repeated the route taken by John Steinbeck in Travels with Charley, none with greater attention to fiction-versus-fact than Bill Steigerwald, whose Dogging Steinbeck: Discovering America and Exposing the Truth about ‘Travels with Charley’ caused consternation among Steinbeck fans for pointing out fibs and fudges in Steinbeck’s record of the 1961 journey he took with the handsome poodle belonging to his wife. Steinbeck set out to rediscover an America he felt he no longer understood, and bringing along Charley was an inspired afterthought. After discovering that Elaine Steinbeck also accompanied her husband much of the way—and that certain encounters reported by Steinbeck were embroidered or created from whole cloth—Steigerwald concluded that Travels with Charley was essentially a work of fiction and should be reclassified as such as in the Steinbeck canon. Academic apologists pushed back, but the dust-up didn’t seem to matter to the dog lovers in the Steinbeck crowd. Charley, who required emergency veterinary care while on the road, remains a hero to them, and Steinbeck is forgiven being a better novelist than journalist.

John Steinbeck set out to rediscover an America he felt he’d lost touch with, and bringing along Charley was an inspired afterthought.

Unlike Steigerwald, Denizet-Lewis isn’t interested in debunking myths, exposing errors, or judging merits. Motivated by behavior problems with his un-Charley-like male labrador, he decided to take a dog owner’s drive across an America that would, today, seem more alien to John Steinbeck than ever. When Denizet-Lewis began discussing plans with friends, Steinbeck’s name kept coming up in conversation and the Charley tie-in was added, like Charley himself when Steinbeck made travel plans more than 50 years ago. Less ambitious in purpose than Steinbeck’s project of moral discovery, the account of the journey Denizet-Lewis shared with Casey records the pains and pleasures of canine rather than human companionship. Steinbeck noted that no two journeys are ever alike (“a trip takes us,” not the other way around). Of our canine companions, observes Denizet-Lewis, “They own us, we don’t own them.”

Searches for America’s Soul Since Travels with Charley

Writers who have ridden the roads and rails to record the features of America’s changing identity since John Steinbeck’s odyssey with Charley include Joel Garreau (The Nine Nations of North America, 1981), William Least Heat-Moon (Blue Highways: A Journey Into America, 1982), Gregory Zeigler (Travels with Max: In Search of Steinbeck’s America Fifty Years Later, 2010), Steinbeck and Denizet-Lewis’s fellow Californian Bill Barich (Long Way Home, On the Trail of Steinbeck’s America, 2010), and On the Road with Charles Kuralt (1995). Kuralt, the amiable TV journalist with a Sunday-morning perspective on America, expressed a self-evident truth about the sub-genre: “Even the best of them never got it all into one book, because the country is too rich and full of contradictions.”

Charles Kuralt, the amiable TV journalist with a Sunday-morning perspective on America, expressed a self-evident truth about the sub-genre: ‘Even the best of them never got it all into one book, because the country is too rich and full of contradictions.’

Like Denizet-Lewis, however, Steinbeck was a bleeding-heart dog lover, and canine characters people his most popular fiction. Examples? Pirate’s faithful entourage in Tortilla Flat, the bunkhouse mutt killed for the sin of getting old in Of Mice and Men, and the Joads’ family dog, the first member to die on the journey west in The Grapes of Wrath. Travels with Charley isn’t as sad as The Grapes of Wrath (Charley survives surgery), and Travels with Casey says less about Steinbeck than Dogging Steinbeck, though Denizet-Lewis, a Steinbeck fan, acknowledges Steigerwald’s book. But Denizet-Lewis’s focus is animal rights, not arguments about authors. Since dog lovers comprise a bigger audience than Steinbeck readers, that strategy (as Steinbeck might say) seems wise.

Ryder W. Miller inspired this review and provided the list of books written “in search of America” since John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley.

Did John Steinbeck Foresee Reality TV When Writing The Winter of Our Discontent?

What does today’s reality TV have to do with John Steinbeck? More than you may think—unless you’ve read The Winter of Our Discontent, set in a remote Long Island village 65 years ago. Now even more than then, it’s fair to say that America has an obsession with celebrity culture and the concept of “instant celebrity.” In its current form this obsession is, perhaps, the ultimate expression of the get-rich-quick impulse dramatized by Steinbeck in the novel: do almost nothing and reap instant rewards.

Now even more than then, it’s fair to say that America has an obsession with celebrity culture and the concept of ‘instant celebrity.’

Nothing better expresses this drive than the popularity of reality television shows like Big Brother and Survivor. Shows such as these feature contestants who do little more than lie, scheme, and debase themselves for a chance at instant riches and fame.

Defenders of reality television often point to series like American Idol and America’s Next Top Model as shows that do reward genuine talent. However, even these programs seem obliged to showcase the worst side of human behavior. Just think of the tone deaf-contestants from American Idol for an unpleasant reminder of people desperately flailing towards immediate fame and fortune while the world laughs at their failures.

John Steinbeck predicted this trend in The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel. Let’s take a brief look at the plot, which concerns Ethan Hawley, a struggling grocer whose family was once one of the most prominent in town.

John Steinbeck predicted this trend in ‘The Winter of Our Discontent,’ his last novel.

Ethan’s people earned their prominence the old-fashioned way: working hard for generations and honestly investing the money they made from fishing, trade, and land. However, Ethan’s father squandered the family fortune with well-meaning but ill-considered plans, and despite his Harvard degree, Ethan has come down in the world.

Although Ethan is honest at heart, he feels the sting of the town’s judgment towards his fallen state. He suffers acutely from the disappointment of his family, especially his children, who view him as little more than an antiquated joke. He is a modern man in pain because of the conflict between a noble past and a bleak future.

One of the last bastions of decency in the community, Ethan is surrounded by people who have adapted to the times: they have built their success on scheming, lies, and betrayal. In the course of the novel he betrays his morals and his honesty to gain the power and financial success craved by his status-conscious wife and their teenage children, a boy and a girl. John Steinbeck’s analogy is quite clear: the Hawley family situation represents the post-World War II transformation of America from a thrifty, hardworking society into a dishonest consumer-culture.

Steinbeck’s analogy is quite clear: the Hawley family situation represents the post-World War II transformation of America from a thrifty, hardworking society into a dishonest consumer-culture.

As a result, The Winter of Our Discontent was admired in Europe and attacked by critics in the USA. Peter Lisca, a leading scholar friendly to Steinbeck, went so far as to describe the book as “undeniable evidence of the aesthetic and philosophical failure of [Steinbeck’s] later fiction” when it was published in 1961.

However, Lisca changed his tune in the 1970s, explaining that Steinbeck had skillfully grasped the essence of the emerging American condition, something readers seemed unaware of at the time, despite the radio-payola and TV game-show scandals permeating the news when Steinbeck wrote The Winter of Our Discontent.

Though Ethan Hawley refects a communal heritage under attack from within, his son Allen—a cheater who believes in looking out for Number One—represents the end result of the moral degradation underway in the popular culture of the late 1950s and 1960s. Allen’s behavior and beliefs continue to astonish readers of The Winter of Our Discontent, for they accurately and eerily predict our contemporary cult of instant celebrity and the unethical and unscrupulous means by which media fame is often achieved.

Though Ethan Hawley reflects a communal heritage under attack from within, his son Allen—a cheater who believes in looking out for Number One—represents the end result of the moral degradation underway in the popular culture of the late 1950s and 1960s.

When we meet him, Allen is something of a lazy lay-about who constantly talks about finding a way to earn a spot on a national quiz show. By the end of the novel, he actually achieves this goal by doing something neither the reader or his father would ever have imagined within his capacity: writing an award-winning essay on the theme of patriotism.

Surprised but gratified, Ethan is proud of his son until a contest runner-up reveals that Allen’s essay is a complete sham. Every single word was stolen from other writers.

When Ethan confronts him, Allen admits that he feels no guilt in his actions because he believes the ends justify the means: committing an immoral or unethical act is worth the reward of success and celebrity. In fact, he believes that he’s just doing what everybody else in Eisenhower-era America does to get ahead—lie, steal, and cheat their way to the top.

Allen admits that he feels no guilt in his actions because he believes the ends justify the means: committing an immoral or unethical act is worth the reward of success and celebrity. In fact, he believes that he’s just doing what everybody else in Eisenhower-era America does to get ahead—lie, steal, and cheat their way to the top.

Despite or because of immoral plans of his own, hatched in secret to satisfy his family’s demands for money and status, Ethan is especially upset that Allen’s actions are rewarded when Allen’s dishonesty is revealed. The essay contest runner-up admits that Allen’s deception will be kept under wraps to avoid embarrassment to the sponsors—a reminder of how the TV game show and pay-to-play radio scandals of the time were handled, to John Steinbeck’s dismay.

Today his point is even more obvious. Written in sadness and anger, The Winter of Our Discontent predicts what John Steinbeck viewed as a moral dead-end for America, one that he saw as unavoidable if left untreated. Allen’s success-at-any cost drive to win is perfectly mirrored by the vapid preening and desperate pleading for 15 minutes of ill-gotten fame by reality-show celebrities. And Americans are still watching.

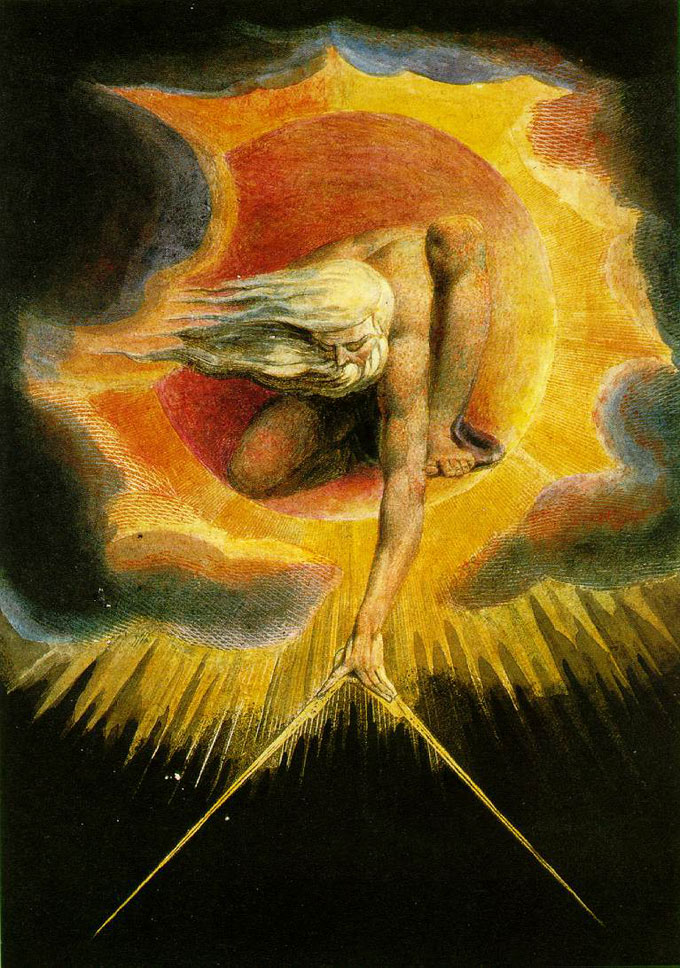

Beyond Russell Brand and Naomi Klein: William Blake, John Steinbeck, and the Politics of Poetic Power

A summary of recent books by Russell Brand and Naomi Klein about current events, global conflict, and corporate accountability associated their views with John Steinbeck and William Blake, the English poet and artist admired by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. But how accurate is it to compare literary artists like Blake and Steinbeck with activists like Naomi Klein or Russell Brand, cultural critics whose appeal is topical and in the moment? It’s true that all four writers oppose oppression and speak truth to power in their work. But the similarity ends there, and the earlier discussion ignored another English poet: John Milton, a writer who has more in common with John Steinbeck and William Blake than Russell Brand or Naomi Klein.

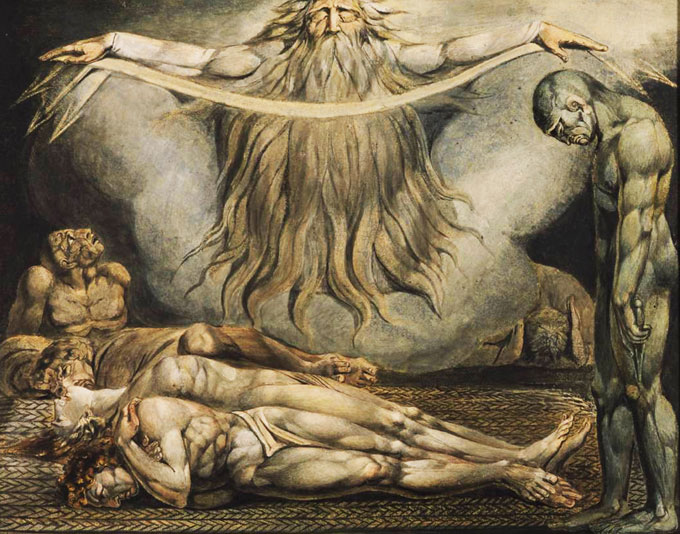

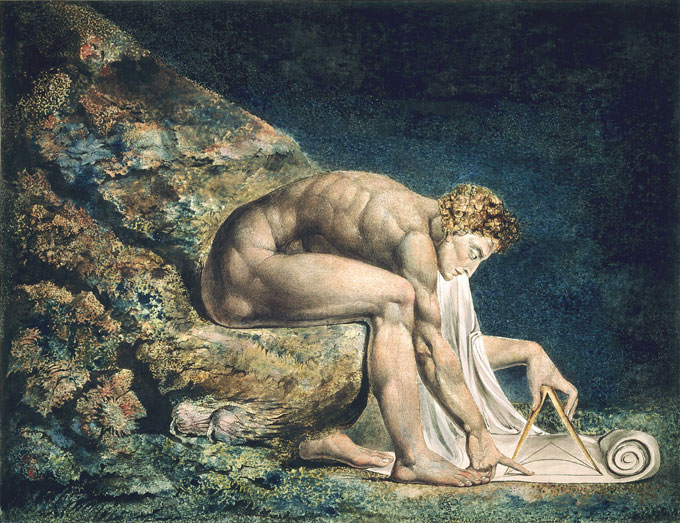

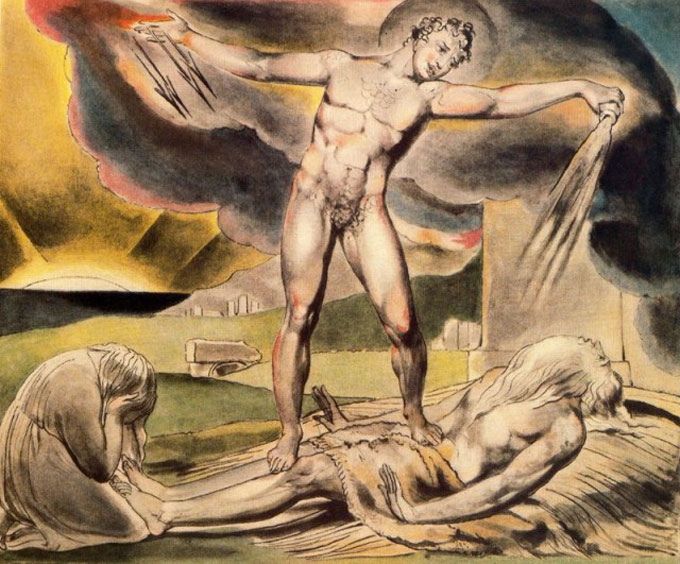

William Blake’s dramatic etched and painted images—drawn from the Bible, world mythology, and Blake’s imagination—have been speaking powerfully since he died in poverty in 1830 and are sampled here for readers unfamiliar with his extraordinary art. His reach is cosmic, and the significance of his work is symbolic, not local or literal like modern writers. Likewise, John Steinbeck’s fiction, even at its most realistic, transcended the time and place in which it was set and tells a universal story applicable to every age. I consider both Blake and Steinbeck to be prophetic poets, like John Milton, who explored the human spirit and who will be read for years to come. Klein is an accomplished journalist and Brand’s jeremiads are often amusing, but neither achieves the depth or breadth to justify comparison with John Steinbeck or William Blake. The Bible and John Milton tell me so.

John Steinbeck, William Blake, and the Politics of Poetry

Blake and Steinbeck championed the downtrodden and called out the kings and corporations responsible, in their view, for pervasive poverty, inequality, and political corruption when they were alive. The context of Blake’s writing included the three great revolutions of his time—the political revolutions in America and France, which he praised, and the industrial revolution in England that created the “dark Satanic mills” he decried. Volumes have been written about the political origins and implications of Blake’s work within the framework of the English Romantic movement of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, and Byron. Like Byron and sometimes Shelley, Blake was a rebel with a cause. But Blake was also a religious visionary, and the Bible inspired his art, not political pamphlets, love affairs, or misadventures in foreign lands.

Wordsworth started in the same radical vein, supporting the French Revolution and opposing urbanization, commodification, and the industrial revolution’s displacement of England’s agricultural poor. If this sounds familiar, it’s because John Steinbeck tells a similar story in The Grapes of Wrath (a Biblical title with a Blakean ring). But Wordsworth became a conservative in old age, writing sonnets praising duty and domesticity that promoted comfort with the status quo. Likewise, John Steinbeck defended America’s intervention in Vietnam, causing various liberal friends and literary critics to view him as a turncoat against progressive principles. As with Wordsworth, Steinbeck’s late-life change damaged his reputation as a public figure. At a minimum it complicates matters when comparing him to William Blake, Naomi Klein, or Russell Brand—a passionate ranter whose first name should be Fire. Unlike Steinbeck, Klein, or Brand, Blake was involved in a lifelong project of deconstructing social theory into metaphysical truth, ridiculing parties and politicians until the day he died. Like Steinbeck, however, he distrusted polemics and rejected identification with any ideology.

Why do we continue to read William Blake and John Steinbeck with a shock of recognition at old truths made new? Because their politics of poetry transcends time and place and speaks to every age. (We’ll see whether Naomi Klein and Russell Brand have the same appeal for readers generations from now.) Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath portray the Biblical symbol of a barred Paradise following a human Fall, an ancient archetype that powerfully the expresses the human condition. Like William Blake, John Steinbeck discovered the origin of evil in the Snake within each of us: the self-divided consciousness that conflicts every person who is truly alive. Tip O’Neill, the former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, claimed that “all politics is local.” Russell Brand appears to agree, while Naomi Klein thinks global politics matter most. Neither point of view pierces the human heart where Blake and Steinbeck find the beginning of all conflict, global or local. Today we don’t read William Blake as counterpoint to John Stuart Mill, or John Steinbeck as ally or antidote to Karl Marx. Connecting Brand and Klein to Marx and Mill makes more sense than wishful thinking about “channeling” John Steinbeck.

Russell Brand, Naomi Klein, and the Ideology of Politics

But differences between the art of John Steinbeck and that of William Blake are worth noting. The Grapes of Wrath depicts the triumph of predatory capitalism over family farming as a fight between political interests with conflicting ideologies. While denying that he was an ideologue, Steinbeck supported the New Deal and (to his credit) took sides in the fight. Russell Brand and Noami Klein, on the other hand, don’t pretend to be above politics, interpreting current events as a clash of ideologies, not cultures or faiths. In an era of even bloodier revolution, William Blake saw every ideology as a form of mental tyranny, “mind-forg’d manacles” that tie down the soul and perpetuate the cycle of conflict among individuals, interest groups, and nations. It was the spirit, not the ideology, of revolution that engaged Blake’s imagination as a writer.

Blake believed that the work of the artist and poet is to help free individual consciousness from conceptual chains, like the prophet Ezekial in “A Memorable Fancy.” Blake’s reference to native cultures sounds very modern:

I then asked Ezekiel why he ate dung, and lay so long on his right and left side. He answer’d, ‘The desire of raising other men into a perception of the infinite: this the North American tribes practise, and is he honest who resists his genius or conscience only for the sake of present ease or gratification?’

John Steinbeck’s version of Blake’s Ezekial figure is the preacher Jim Casy in The Grapes of Wrath, a prophet who endures pain to “cleanse the doors of perception” and achieves salvation through self-denial, self-sacrifice, and self-transcendence. Jim Casy dies in Steinbeck’s story but, like Tom Joad, his holy ghost lives on. In Dubious Battle presents a similar pattern of questioning introspection and self-transcendence in the character of Doc, the doubting physician who sees beyond the conflicting ideologies of capitalism and communism to a cosmic vision worthy of William Blake: Group Man as godlike, a corrupted version of Blake’s “human form divine.” Ed Ricketts has been identified by scholars as the inspiration for each of these characters in John Steinbeck’s fiction; it’s worth noting that Ricketts deeply distrusted ideology and rejoiced in reading William Blake, one of a handful of ageless poets he identified as “breaking through” to higher vision and cosmic consciousness in their art.

John Steinbeck, William Blake, and their Poetic Prophets

Blake always called his poetic vision “prophetic.” Steinbeck presents both prophetic figures—In Dubious Battle’s physician Doc, The Grapes of Wrath’s preacher Casy—in the same mode of thought and speech. Each is a seer in two senses, like Blake’s Old Testament prophets: they see into the human soul and they see into the immediate future. Doc speaks of “the Blood of the Lamb.” Casy’s dialog becomes increasingly poetic as the novel progresses, as when he prays reluctantly over a woman dying on the exodus to the Promised Land of California. Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost must also be kept in mind to complete the picture. Blake and Steinbeck were intimately familiar with Milton’s great narrative of human fall from grace, innocence, and Paradise. Blake considered Satan the true hero of Milton’s poem because Satan, not God, represents energy, imagination, and “breaking through,” and Steinbeck was familiar with Blake’s radical reinterpretation of Milton’s moral message. It clearly colors Casy’s rejection of religion and helps us understand Doc’s prophecy about the ambiguous outcome of the “dubious battle” (a phrase borrowed from Paradise Lost) between the strikers and police.

Which brings us back to Russell Brand and Naomi Klein. Neither writer has John Milton, William Blake, or John Steinbeck’s grounding in the prophetic literature or language of the Bible, and the gap is apparent. As a result, reading either one feels a bit like skating on thin ice. Firebrand rhetoric (Brand) and statistical analysis (Klein) fail to convey the sense of depth and permanence about politics found in John Steinbeck, who has far more in common with William Blake and John Milton than with Russell Brand or Naomi Klein. It might be better to describe Steinbeck as channeling these writers than to assert that Klein or Brand has channeled John Steinbeck in books that, however relevant they seem today, are too busy taking the pulse of the body politic to get to the heart of the matter.

Of Mice and Myth: John Steinbeck, Carl Jung, and The Epic of Gilgamesh

John Steinbeck’s short novel Of Mice and Men is a powerful exploration of isolation, disenfranchisement, and problems of social integration in an era of cultural fracture. Divided by class, race, and gender, its characters struggle to assimilate into the small social world of a 1930s California ranch. But Steinbeck’s story possesses a timeless dimension as well—one that bears examination in the context of the psychologist Carl Jung’s concept of the unconscious and of two ancient narratives: the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh and the Genesis story of Jacob and Essau.

Carl Jung and Of Mice and Men as Mythic Pattern

Some critics argue that the appeal of Of Mice and Men derives from its dramatization of universal themes, while others suggest that its continued popularity results from its depiction of the reality of the lives of migrant ranch workers: from the power of realism and relevance. However, there is at least one other way to explain the novel’s resonance with readers of every type. Certain formal elements open Of Mice and Men to a mode of criticism that is interested not in realism or in theme alone, but in the psychological relationship of theme to character, specifically the potent symbolism of the character pair comprised by George and Lennie.

Carl Jung’s psychoanalytical vocabulary and myth criticism offer insights into the significance of Steinbeck’s use of a traditional archetype in describing George and Lennie, suggesting that much of the novel’s power derives from an ancient mythic pattern. Employing the character-pair archetype also found in The Epic of Gilgamesh and the Genesis story of Jacob and Esau, Steinbeck invites us to consider a fundamental principle of personal psychology and myth narrative that is related to Carl Jung’s transcendent function of the unconscious.

Carl Jung’s psychoanalytical vocabulary and myth criticism offer insights into the significance of Steinbeck’s use of a traditional archetype in describing George and Lennie.

In this context, Of Mice and Men can be taken as an example of a specific psychological process, rendered artistically, that seeks to externalize the relationship between the conscious ego and the unconscious, a process Carl Jung describes in his 1916 essay “The Transcendent Function.” In fiction and poetry, as in myth, we see this process take place through narrative and metaphor. The purpose of the process is the achievement of psychological balance. The tools of the process are mythogenes, the building blocks of myth—images drawn from the collective unconscious that facilitate communication between the conscious and unconscious parts of the mind. In art, the result of the process is often the creation of a myth narrative.

Along with a number of classic myth narratives that express this transcendent function in the acts of gods and heroes, we can point to works of modern fiction that represent mythic patterns such as that of the “unassimilated” man or woman estranged by nature from society. William Faulkner’s character Benjy in The Sound and the Fury and John Steinbeck’s Lennie in Of Mice and Men are examples, and Lennie shares similarities, both literal and thematic, with the character Chief in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The Bengy-Lennie-Chief character type is a modern iteration of an ancient archetype: the unassimilated outcast or alien who represents unacceptable or unwanted urges of the unconscious mind and who—despite friendships and affections—is unable to integrate successfully into society. He is the shepherd in an age of farming. He is mute in a time of great debate. He is the man without power over his personal history or his place in society.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, and Steinbeck’s Story

Although Of Mice and Men is enriched by the Jungian archetype of the unassimilated man, the novel’s echo of The Epic of Gilgamesh and the Biblical story of Jacob and Esau is equally consequential. All three narratives depict a character pair in which one individual, the true hero, is bonded by birth and fate to the other, the unassimilated man. The parallels are striking in number, detail, and effect: on multiple levels, George and Lennie are Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Jacob and Esau. Though The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Genesis story, and Of Mice and Men differ in other ways, each focuses on a pair of characters who appear to be cut from the same cloth—the “cloth” of mythology that Carl Jung identified as the material of the collective unconscious.

In Of Mice and Men, Lennie is the character with the closest relationship to the Jungian concept of the unconscious. Driven by animal impulses that he is unable to control, Lennie enters the scene trailing behind George through the brush, “a huge man, shapeless of face, with large pale eyes, with wide, sloping shoulders [. . .] dragging his feet a little, the way a bear drags his paws” (Steinbeck 798). In the opening chapter, his behavior is likened to that of a carp and a horse; going to the river, he “drank with long gulps, snorting into the water like a horse” (Steinbeck 798). Animalistic images and associations are carried through to the climax of the novel in which Lennie’s uncontrolled violence is compared to that of a wild beast. In the end, he returns to the river, “as silently as a creeping bear moves” (Steinbeck 872). Throughout, he is drawn to small creatures—mice, puppies, and rabbits—and he threatens to flee the society of the ranch to live in a cave.

In Of Mice and Men, Lennie is the character with the closest relationship to the Jungian concept of the unconscious.

Enkidu in Gilgamesh and Esau in Genesis share these qualities. Born in the wilderness, Enkidu is described as having a body that is “rough” and “covered with matted hair” (Gilgamesh 63). Just as Lennie is attracted to the solitude of the river, Enkidu “had joy of the water with the herds of wild game” (Gilgamesh 63). Like Lennie, Enkidu is physically strong but mentally unprepared for social survival (Gilgamesh 65); his bond with the animals of the wild is broken when a harlot teaches him the ways of society (65). Arriving in the city, he establishes a bond of brotherhood with Gilgamesh and becomes tasked with the guardianship of the hero, who is the king of Uruk. Genesis describes Esau similarly—a hairy man, a shepherd and hunter at home with wildlife and wilderness (Tanakh 38). When Jacob wants to pass as Esau, his older brother, he puts goat hide on his hands and the neck (Tanakh 41). When Esau complains to Jacob that he is hungry, he demands that Jacob give him some of the “red stuff,” trading his birthright for a bowl of stew (Tanakh 38). Esau’s appetite for “red stuff” is echoed in Lennie’s demands for ketchup in Of Mice and Men (Steinbeck 804). Like Enkidu and Lennie, Esau is undone by a woman (Tanakh 43).

However, in the pairing of an unassimilated man with a heroic companion in Genesis, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and Of Mice and Men, relationship transcends individual identity. George and Lennie’s mythic significance lies in the nature of their archetypal connection with one another. As characters, they are both complementary and opposite, two halves of a codified relationship and two parts of a single unit. Their antecedents in the older stories—Jacob and Esau, Gilgamesh and Enkidu—are brothers. Steinbeck’s pair wears the same clothes (Steinbeck 797-798) and speaks a single voice (Steinbeck 812, 815), brothers in behavior if not by birth.

In the pairing of an unassimilated man with a heroic companion in Genesis, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and Of Mice and Men, relationship transcends individual identity.

Of the two, George is sharper and worldlier, “small and quick, dark of face, with restless eyes and sharp strong features” (Steinbeck 798). Just as Jacob in Genesis conducts business shrewdly (Tanakh 47), George proves capable of negotiating, manipulating, and conducting business with surprising skill (Steinbeck 802, 842). Gilgamesh, too, is savvy, smoothing the way for his quest by manipulating the powers that be in Uruk (Gilgamesh 72). The figures of George, Jacob, and Giglamesh dominate each of the fraternal relationship, not by seniority but through their ability to integrate with society and play by its rules.

While the less adept, unassimilated character remains a social weight on his socially skillful partner, this drag is accepted by both parties. Though “Lennie’s a God damn nuisance most of the time” (Steinbeck 41), George feels the obligation to protect him at any cost. For Jacob, Esau represents a function of reality itself, unavoidable and equally permanent. The fear of Esau felt by Jacob is significant and suggests Carl Jung’s concept of the Shadow self. Likewise, Lennie and Enkidu can be seen in terms of fear and Shadow—Jung’s term for the suppressed but active elements of the unconscious (Jung 146). The tie that binds each pair of characters is deep, dark, and definitive. Viewed in social terms, the unassimilated man in all three stories prevents his more socially adept partner from fully entering into and succeeding in the world. The psychological dynamic that results creates conflict: the socialized character must eliminate his animalistic, amoral, and unassimilated Shadow self to achieve complete social integration.

Viewed in social terms, the unassimilated man in all three stories prevents his more socially adept partner from fully entering into and succeeding in the world.

But the dominant partner has other gifts as well. George, a “smart little guy” (Steinbeck 825), is able to read the signs in a situation and, in a way, prophesy the future. Similarly, both Jacob and Gilgamesh possess the power of divination, interpreting dreams (Gilgamesh 78) and seeing visions—the stairway to heaven—while wrestling with angels (Tanakh 43, 52). Early in Of Mice and Men, George predicts trouble with Curley’s wife (Steinbeck 820), repeatedly voicing his anxiety about the probable outcome: “She’s gonna make a mess. They’s gonna be a bad mess about her” (Steinbeck 835). Though this sounds to us like common sense, no other character in Of Mice and Men “gets it” as George does. The other men in the bunkhouse recognize Curley’s wife as a threat, but none sees or says what seems inevitable.

The final vision described in The Epic of Gilgamesh is particularly remarkable in relation to George’s prophetic power in Of Mice and Men. Lamenting over his dying brother, Gilgamesh cries, “The dream was marvelous but the terror was great; we must treasure the dream whatever the terror; for the dream has shown that misery comes at last to the healthy man . . . .” (Gilgamesh 93). In this way Gilgamesh reads the last dream of Enkidu in which Enkidu is approached by a woman who questions him before awakening “like a man drained of blood who wanders alone in a waste of rushes; like one whom the bailiff has seized and his heart pounds with terror” (Gilgamesh 92-93). In narrative detail and poetic imagery, this passage presages the climactic conclusion of Of Mice and Men: Lennie flees after being questioned by a woman; terrified, he moves alone through the brush along the Salinas River. His dream of tending rabbits in a happy future with George dies, like Lennie himself—and like Enkidu, who leaves his bereaved partner Gilgamesh in “misery,” muttering about failed dreams.

Of Mice and Men: Social Commentary or Timeless Myth?

Applying Jungian psychoanalytical theory to Of Mice and Men is not the most common critical approach to John Steinbeck’s most widely read novel. The social realism of the text and its topical themes relating to migrant labor, disenfranchisement, and the American Dream typically take precedence over readings that emphasize the work’s psychological elements, raising this question: Can a work of social realism be read as myth or as psychological allegory?

In response, one might argue that the simplicity of setting, character, and dialog—as well as the deliberate use of types and stereotypes (racial, gendered, professional, intellectual, and class-based)—invites both political and psychological/symbolic interpretation. As noted by John Steinbeck’s sometime-friend, the mythologist Joseph Campbell, formalized tropes of character and setting are precisely the stuff of myth (Campbell 12-15). As much as Of Mice and Men may be read as a social-realist text, therefore, it is realistic only insofar as it is interested in the social and political issues of its era. In style and formula it falls neatly into the timeless categories of symbolic and myth literature, forms of narrative in which the application of Carl Jung’s insights are particularly fruitful.

Can a work of social realism be read as myth or as psychological allegory?

The archetypal pair represented by George and Lennie in Of Mice and Men evokes two principles of Jungian psychoanalytic theory: the Shadow and the transcendent function, concepts related to the individual ego’s relationship with the unconscious. As in the example of Jacob and Esau, the unassimilated character is associated with impulsive, irrational, and anti-social behavior. Like Lennie, Esau represents the Jungian Shadow, characterized by “uncontrolled or scarcely controlled emotions [. . .] like a primitive” and “singularly incapable of moral judgment” (Jung 146). The individual ego both desires and fears communion with this dark element of the unconscious: in the end the ego wants to exorcise the Shadow in an ultimately transcendent function.

If Lennie is the submerged Shadow, George is the ruling ego—aware, socialized and civilized—for whom the threat of the unconscious will exist until the transcendent function is enacted and the Shadow has been purged by being brought to light. According to Carl Jung, this takes place when the two forces, ego and Shadow, achieve a direct and “compensatory relation” to one another (Jung 294). The means may be aesthetic, as the ego attempts to formalize the formless unconscious and the repressed unconscious attempts to “rise” into conscious mind. In this way the transcendent function “manifests itself as a quality of conjoined opposites” (Jung 298); the goal is for the ego to find the “courage to be oneself” (Jung 300), a state of psychological singleness that George accomplishes when he shoots Lennie.

If Lennie is the submerged Shadow, George is the ruling ego—aware, socialized and civilized—for whom the threat of the unconscious will exist until the transcendent function is enacted.

Thus George and Lennie can be interpreted as two parts of one “mind,” symbolically undergoing the necessary process of overcoming a latent set of “wild” impulses that impede full social integration. As long as George keeps Lennie with him, he will never “stay in a cat house all night long” or “set in a pool room and play cards or shoot pool” (Steinbeck 804). Impulsive, ungovernable, and “incapable of moral judgment,” Lennie holds George back from normal social activity. When Candy shows George the dead body of Curley’s wife, George’s social future in the predictable aftermath is his first concern. When Candy asks George if the plan to buy their own ranch is off, George replies by forecasting a future in which he can “stay all night in some lousy cat house. Or I’ll set in some pool room till ever’body goes home” (Steinbeck 868).

But Lennie’s representation of the unconscious goes beyond his relationship with George. Uniquely within the world of Of Mice and Men, Lennie has the ability to bring out the impulsiveness latent in other characters and to engage them in conversations about dreams, resentments, and other emotions. His conversation with Crooks demonstrates this trait, as Crooks breaks with social convention to let Lennie into his room and explore hidden feelings that he suppresses with everyone else (Steinbeck 849). A similar dynamic characterizes Lennie’s conversation with Curley’s wife when she divulges things that she “ain’t told [. . .] to nobody before” and “ought’n to” (Steinbeck 863). Not only is Lennie incapable of self-control; he inspires this incapacity, however briefly, in others as well.

Not only is Lennie incapable of self-control; he inspires this incapacity, however briefly, in others as well.

Duality of mind and will is a common theme in mythology and in modern literature. Steinbeck’s use of the archetypal character pair in Of Mice and Men dramatizes this duality, offering us a deeper understanding of its meaning. As in much American writing of the 1930s, social repression and human disenfranchisement function socially and politically as facts of contemporary life. But they are also internalized. Ironically, the humble American dream of property ownership is aligned in the narrative with irrational, unconscious urges, with the primitive and undeveloped Shadow represented by Lennie. To survive in the hard world of Of Mice and Men, characters like Crooks suppress their desire for friendship in favor of being accepted, abstractly and impersonally, by the group. Characters like Curley’s wife are shunned and isolated because they are associated with desires that the group considers taboo. Lennie, unassimilated and unsocialized, accesses these suppressed elements in others, bringing them briefly into the open until he can be eliminated.

Ironically, the humble American dream of property ownership is aligned in the narrative with irrational, unconscious urges, with the primitive and undeveloped Shadow represented by Lennie.

On a literary and functional level, Steinbeck’s archetypal character pair serve as a vehicle for demonstrating social values and for considering a compelling question: What must be eliminated from consciousness—from the ego personality—in order for an isolated individual to integrate with society? Steinbeck’s answer is painfully clear. As one partner dies, a path opens for the survivor. In The Epic of Gilgamesh, the survivor is made king. In Genesis he becomes the father of nations. Unlike Genesis and Gilgamesh, however, Of Mice and Men constitutes a sad and somber commentary on group values and cultural norms. To survive, a man must put away his innocence and his love for “nice things.” He must be hardhearted and ruthless. He must not dream.

What must be eliminated from consciousness—from the ego personality—in order for an isolated individual to integrate with society? Steinbeck’s answer is painfully clear.

By the time Of Mice and Men ends, George has acknowledged and accepted the severity of this requirement, proving his emotional and psychological fitness for social survival in a difficult environment. His world is heartless, but he can cope: He has eliminated his unacceptable impulses—embodied in Lennie—by slaying them. If we accept the literary critic Alfred Kazin’s axiom that “psychology is always less true than art,” we can hope, at least, that applying Jungian psychoanalytical criticism to Of Mice and Men does not lower Steinbeck’s art to the level of psychology but raises psychology to the level of art. Seen in this light, the power of Steinbeck’s most popular novel can be located, in large part, in the writer’s use of mythic archetypes to explore a psychological truth.

Works Cited

Anonymous. The Epic of Gilgamesh. London: Penguin Books. 1972. Print.

Anonymous. Tanakh. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society. 1985. Print.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 3rd Edition. Novato, California: New World Library. 1949. Print.

Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury. New York: Random House. 1929. Print.

Jung, Carl. “The Transcendent Function.” The Portable Jung. New York: Penguin Books. 1976. 273-300. Print.

Kazin, Afred. The Inmost Leaf. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1941. Print.

Kesey, Ken. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. New York: Penguin Books. 1962. Print.

Steinbeck, John. Of Mice and Men. Steinbeck: Novels and Stories 1932-1937. New York: Literary Classics of the United States. 1994. 795-878. Print.

Party! Susan Shillinglaw on Reading The Grapes of Wrath

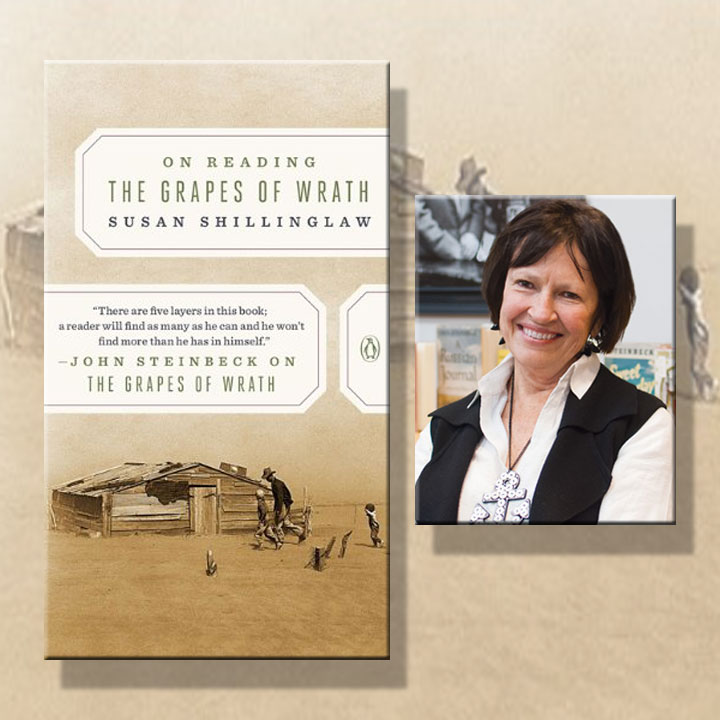

Great books about great books are cause for celebration anytime. Thanks to the pressure of a 75th anniversary deadline—and the prodding of the people at Penguin Books—John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath now has a perfect companion in On Reading “The Grapes of Wrath” by Susan Shillinglaw, professor of English at San Jose State University. Recently published by Penguin Books as an attractive, affordable paperback, her new book is an essential guide to a novel that was written in nine months in 1938 and still sells in six figures—further evidence, if needed, that deadlines are enlivening. A compact work of 200 pages divided into engaging topics, the project was suggested by Penguin Books and completed by Shillinglaw in 90 days. Written in clear prose for a general audience, it will still be read when The Grapes of Wrath turns 100.

Great books about great books are cause for celebration anytime. Thanks to the pressure of a 75th anniversary deadline—and the prodding of the people at Penguin Books—John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath now has a perfect companion in On Reading “The Grapes of Wrath” by Susan Shillinglaw, professor of English at San Jose State University. Recently published by Penguin Books as an attractive, affordable paperback, her new book is an essential guide to a novel that was written in nine months in 1938 and still sells in six figures—further evidence, if needed, that deadlines are enlivening. A compact work of 200 pages divided into engaging topics, the project was suggested by Penguin Books and completed by Shillinglaw in 90 days. Written in clear prose for a general audience, it will still be read when The Grapes of Wrath turns 100.

Susan Shillinglaw’s new book is an essential guide to a novel that was written in nine months in 1938 and still sells in six figures.

San Jose State University’s reputation for Steinbeck studies rests largely on Shillinglaw’s 25-year record of teaching, writing, and organizing around California’s greatest author of all time; in international Steinbeck circles, perhaps three other scholars in America come to mind as quickly as she does when Steinbeck studies are mentioned. The late Peter Lisca unlocked the structure of Steinbeck’s fiction using the tools of formal analysis. Jackson Benson, another Californian, wrote the definitive biography. Robert DeMott—the first director of San Jose State University’s center for Steinbeck studies—continues to explore the sources, texts, and processes of Steinbeck’s writing with the care of a scientist and the soul of a poet.

San Jose State University’s reputation for Steinbeck studies rests largely on Shillinglaw’s 25-year record.

Shillinglaw builds on all three in her new book, combining structural, biographical, and textual approaches with features that have become her signature as a writer about Steinbeck. As in her previous publications, she brings Steinbeck out of the past into the present, connecting the context, content, and impact of The Grapes of Wrath to urgent issues of contemporary life. As she has done in essays and conferences, she brings Steinbeck’s ecology into existential focus through the writer’s relationship with Ed Ricketts, connecting The Grapes of Wrath to Sea of Cortez, their collaborative work, in what she describes as a “diptych” of two books with one theme. Most important for most readers, she brings a graceful style of expression to an author who cared more about being read than being written about. In this she emulates her subject; On Reading “The Grapes of Wrath” is further evidence of the all-too-rare virtue of readability.

Shillinglaw brings a graceful style of expression to an author who cared more about being read than being written about.

For such a book the highest praise may be the briefest: On Reading “The Grapes of Wrath” is a one-volume course in John Steinbeck’s masterpiece, efficiently organized, elegantly presented, and easily assimilated in a matter of hours. Wherever you’re headed in this summer of Steinbeck, don’t leave home without it. (Future party alert! This advice will still apply when The Grapes of Wrath celebrates its centennial. Like Steinbeck’s fiction, Penguin Books and On Reading “The Grapes of Wrath” are certain to be around for a very long time.)

John Steinbeck’s Powerful Ambivalence: Book Review

John Steinbeck remained a force in American cultural life for three decades after his so-called years of greatness between 1936 and 1939—a remarkably productive period marked by the publication of In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), The Long Valley (1938), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). On the 75th anniversary of Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, the reasons for its continuing popularity—despite the dismissive evaluations of critics—are worthy of reconsideration.

John Steinbeck remained a force in American cultural life for three decades after his so-called years of greatness between 1936 and 1939—a remarkably productive period marked by the publication of In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), The Long Valley (1938), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). On the 75th anniversary of Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, the reasons for its continuing popularity—despite the dismissive evaluations of critics—are worthy of reconsideration.

‘Critics do not like to be confounded in their attempts to compartmentalize,’ Simon Stowe reminds us in ‘The Dangerous Ambivalence of John Steinbeck,’ his introduction to A Political Companion to John Steinbeck.

“Critics do not like to be confounded in their attempts to compartmentalize,” Simon Stowe reminds us in “The Dangerous Ambivalence of John Steinbeck,” his introduction to A Political Companion to John Steinbeck (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2013), co-edited with Ernesto Zirakzadeh. Stowe shows how Steinbeck’s ambivalence about America, government, community, and individualism confounds Steinbeck’s critics and helps explain the disconnect between Steinbeck’s readers and many academics. Other contributors illuminate other areas of interest with equal vigor.

From The Grapes of Wrath to World War II and Beyond

During World War II, John Steinbeck was subjected to federal background investigations, even as he worked to advance the nation’s cause, writing the much-maligned yet influential novel and play The Moon Is Down (1942)—not explicitly, yet quite obviously about the Nazi invasion of Norway—and Bombs Away (1942, the positive account of a U.S. Air Force bomber team. He traveled to England in June of 1943, then on to North Africa, Sicily, and the Italian mainland to report on the war on the ground for the New York Herald Tribune. He also wrote a pair of works set in Mexico—The Forgotten Village (1941) and The Pearl (1947)—that addressed the ethical complications surrounding the intersections of modern medicine and indigenous folk cultures, followed by Cannery Row (1945), a divergent work that might be considered the first novel of the coming American counterculture.

Cannery Row . . . might be considered the first novel of the coming American counterculture.

While less productive in the 1950s, Steinbeck completed one of his most successful and enduring novels, East of Eden (1952), reflecting the generational conflicts that came to mark the post-war period, as well as Sweet Thursday (1954), the critically undervalued sequel to Cannery Row. In addition, the 1950s saw the publication of John Steinbeck’s screenplay for Elia Kazan’s acclaimed film Viva Zapata! (1952) and Once There Was a War, the writer’s collected World War II dispatches (1958).

In 1966, John Steinbeck reaffirmed his deep attachment to his country in his last book, America and the Americans.

John Steinbeck began the 1960s with what would be his last novel, The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), followed by his endearing and enduring narrative Travels with Charley (1962)—an attempt to reconcile his growing sense of alienation from his culture—and the Nobel Prize for Literature, awarded in 1962 over the lamentable protestations of his critics. In 1966, he reaffirmed his deep attachment to his country in his last book, America and the Americans, essays on various aspects of national life and character. In 1966-67 he toured Vietnam, where one of his sons was serving in the U.S. Army. As in World War II, the newspaper dispatches he sent home supported his country and its policies, although he later changed his position regarding his friend Lyndon Johnson’s increasingly unpopular war in Southeast Asia.

Steinbeck and Politics from Great Depression to Cold War

In short, John Steinbeck’s writing of four decades serves as a remarkable guide through the controversies and complications that characterized American politics and culture in the middle third of the 20th century. If it is appropriate to consider the nation in the middle third of the 19th century under the rubric of Walt Whitman’s America, as David Reynolds’ 1995 book of the name has done, and to label the last third of that century Mark Twain’s America as Bernard DeVoto did in his earlier book, then it seems no less reasonable to view the years from the Great Depression to the Great Society through the lens of John Steinbeck’s acute vision, as Cyrus Ernesto Zirakzadeh and Simon Stow do in A Political Companion to John Steinbeck. A strong addition to the excellent series of volumes called Political Companions to Great American Authors—one that includes Henry Adams, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson—the anthology attempts a fuller consideration of Steinbeck’s centrality to at least the first part of American life and politics in the mid-20th century.

John Steinbeck’s writing of four decades serves as a remarkable guide through the controversies and complications that characterized American politics and culture in the middle third of the 20th century.

Not surprisingly, Steinbeck’s work in the 1930s and 1940s gets most of the attention of the book’s many contributors. This includes co-editor Zirakzadeh’s provocative discussion of Steinbeck as a “revolutionary conservative or a conservative revolutionary”; Donna Kornhaber’s treatment of politics and Steinbeck’s playwriting; Adrienne Akins Warfeld’s examination of Steinbeck’s Mexican works from the 1940s; Charles Williams’ insightful exploration of Steinbeck’s “group man” theory in In Dubious Battle; the volume’s standout essay by James Swensen on Dorothea Lange’s photographs and the work of the John Steinbeck Committee to Aid Agricultural Organization; Zirakzadeh’s treatment of The Grapes of Wrath as novel, film, and inspiration for the music of Bruce Springsteen; and Mimi R. Gladstein and James H. Meredith’s “Patriotic Ironies,” an account of John Steinbeck’s wartime service. Other essays examine Steinbeck’s legacy in the songs of Springsteen, Travels with Charley and America and Americans (together), and The Winter of Our Discontent.

John Steinbeck’s Enduring Relevance, Despite the Critics

In addition to the absence of any extended treatment of Cannery Row, the second half of Steinbeck’s career in general gets short shrift. There is no significant coverage of East of Eden, nor of Steinbeck’s powerful defense of the playwright Arthur Miller in 1957 against the charges of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the political context of Cold War paranoia in which HUAC operated. Partisan politics are also largely absent from the essays, although as evident from his correspondence John Steinbeck held strong political opinions, beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s. Steinbeck’s dispatches from the Vietnam War (recently republished by the University of Virginia Press) are ignored, and greater attention to the 1950s and 1960s would have made the anthology more complete. With notable exceptions, senior Steinbeck scholars such as Robert DeMott and Susan Shillinglaw are absent from the roster of contributors: Kevin Hearle’s deep perspective on the politics of race and place would have augmented the volume but is missing.

John Steinbeck held strong political opinions, beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s.

Despite the gaps, however, A Political Companion to John Steinbeck achieves the goal of its editors and contributors to illuminate the complexities of John Steinbeck’s political thought and underscore the enduring contribution of his work to American political thought. Well-edited and integrated, the essays explore nuances and complications of Steinbeck’s personal political thought while providing an effective response to the generations of critics who have found his work excessively heroic, sentimental, moralistic, or didactic—or too popular to be taken seriously. Whatever the tensions in John Steinbeck’s writing at a particular moment—between group man and the individual, traditionalism and liberalism, communism and capitalism, alienation from and affirmation of America—contradictions and ambiguities are distinctive characteristics of his art and ambivalence frequently defines his thinking. These traits help account for his continuing relevance.

Whatever the tensions in John Steinbeck’s writing at a particular moment . . . contradictions and ambiguities are distinctive characteristics of his art and ambivalence frequently defines his thinking. These traits help account for his continuing relevance.

John Steinbeck may not be honored everywhere in the academy 75 years after The Grapes of Wrath, but he remains popular with readers worldwide. His dedication to the advancement of human welfare and the nurturing of human relations through art may seem too low-brow to arbiters of the current literary canon, and political extremists on both right and left continue to attack his work, from In Dubious Battle to The Grapes of Wrath and beyond. But a significant segment of the reading public still feels deeply connected to his fiction. More than any other writer of his day, Steinbeck captured and conveyed the striving of average Americans during the Great Depression, World War II, and two subsequent wars—one cold, the other hot. By placing Steinbeck’s powerful, productive ambivalence center stage, A Political Companion to John Steinbeck nudges us toward a fuller appreciation of the writer and his work in a year in which we celebrate The Grapes of Wrath, his masterpiece.

A different version of this review appeared in The b2 Review.

Despite Cost of Other Literary Journals, Literary Criticism Survives at Steinbeck Review

As scholarly journals become too expensive for non-commercial publishers and too costly for non-institutional subscribers, Steinbeck Review survives, a fortunate exception to the unfortunate fact that many academic journals devoted to literary criticism are no longer economically sustainable. The latest issue, published in December, features literary criticism, history, and news of interest to individual Steinbeck readers. Best of all, an individual subscription remains more affordable than scholarly journals priced for institutional libraries.

As scholarly journals become too expensive for non-commercial publishers and too costly for non-institutional subscribers, Steinbeck Review survives, a fortunate exception to the unfortunate fact that many academic journals devoted to literary criticism are no longer economically sustainable. The latest issue, published in December, features literary criticism, history, and news of interest to individual Steinbeck readers. Best of all, an individual subscription remains more affordable than scholarly journals priced for institutional libraries.

As Scholarly Journals Inflate, Literary Criticism Suffers

Like other literary journals coping with changing market conditions, Steinbeck Review has altered its name, look, and frequency since its founding in 1988 at San Jose State University. Started as one of several literary journals devoted to Steinbeck in the heyday of general scholarly journals and books, it first appeared in newsletter format as Steinbeck Studies, a publication of San Jose State University’s Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies.

By 2004 it had become the most respected academic journal in its field of focus, changing its name to Steinbeck Review and its format to book size and length. The first edition published under the literary journal’s new name and management—outsourced to Scarecrow Press, a respected publisher of scholarly journals and books—contained 170 pages and a call for papers to be read at an international Steinbeck conference in Japan. Literary criticism and history about Steinbeck had become a global growth industry, and Japan was a world leader.

Today international conference costs are beyond reach for some institutions and most individuals, and literary journals specializing in an author not named Shakespeare have become a dying breed. Costs of production have hit scholarly publications in non-scientific fields particularly hard almost everywhere, and new books of literary criticism devoted to Steinbeck are now scarcer than crows in Kyoto. The current issue of Steinbeck Review lists only three books of Steinbeck literary criticism published in the last 12 months. We wrote about two of them at SteinbeckNow.com. The third, A Political Companion to John Steinbeck, isn’t literary criticism.

Literary Criticism, Literary Journals, and Steinbeck Lovers

Fortunately for Steinbeck lovers, Steinbeck Review survives by maintaining its ties to its home at San Jose State and its appeal to the international Steinbeck community. Its latest issue compares favorably with similar literary journals in length and scope but, as Steinbeck wished for his own books during his lifetime, remains both readable and affordable for regular fans. The scholarly journal’s professional editorial team—Barbara Heavilin, Mary Brown, and Paul Douglass—respond personally to questions about submitting articles. Under the expert management of Pennsylvania State University Press, the online submission process is easy to navigate and efficient to operate.

Despite the continuing decline in printed literary criticism about Steinbeck, Steinbeck Review shows every sign of long-term survival. Articles cover a range of topics, from formal literary criticism to personal essays and thoughtful book reviews. Contributors include passionate amateurs like the late Roy Simmonds, as well as academic superstars like Susan Shillinglaw, a living legend and the author of the best book of Steinbeck literary criticism published in 2013. A year’s subscription costs only $35—a fraction of the price of academic books—and includes membership in the John Steinbeck Society of America. Join and subscribe. It’s a two-for-one deal, and Steinbeck—who disliked cost inflation in books written for common readers and disparaged literary criticism produced by the few for the few—would certainly approve.

Essays on John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, Co-Edited by the University of North Carolina’s Henry Veggian

The University of North Carolina’s English department always had a great reputation. I should know. I attended in the 1960s, when American literature was thought to have ended with William Faulkner and John Steinbeck was politely ignored. The distinguished Steinbeck scholar Susan Shillinglaw wrote her doctoral dissertation on James Fenimore Cooper there several years after I finished mine on Blake and Yeats. British literature since Joyce and Woolf was still considered too recent for serious study, despite the presence on campus of Anthony Burgess, author of the wildly subversive novel A Clockwork Orange, published 10 years after Steinbeck’s East of Eden. Both books became successful movies, but were a world apart. So was Tar Heel and Steinbeck Country. At Chapel Hill, “east of Eden” meant the North Carolina backwater between Raleigh and the coast. Statesville may have looked like Salinas; Wilmington was no Monterey.

The University of North Carolina’s English department always had a great reputation. I should know. I attended in the 1960s, when American literature was thought to have ended with William Faulkner and John Steinbeck was politely ignored. The distinguished Steinbeck scholar Susan Shillinglaw wrote her doctoral dissertation on James Fenimore Cooper there several years after I finished mine on Blake and Yeats. British literature since Joyce and Woolf was still considered too recent for serious study, despite the presence on campus of Anthony Burgess, author of the wildly subversive novel A Clockwork Orange, published 10 years after Steinbeck’s East of Eden. Both books became successful movies, but were a world apart. So was Tar Heel and Steinbeck Country. At Chapel Hill, “east of Eden” meant the North Carolina backwater between Raleigh and the coast. Statesville may have looked like Salinas; Wilmington was no Monterey.

But I suspect that both Salinas brothers in East of Eden would have felt right at home as University of North Carolina undergraduates during my time—Cal in the go-getting young business school, Aron under the protective Anglo-Catholic wing of English department traditionalists who genuflected every Sunday during mass at the Chapel of the Cross before chatting over sherry about the Anglo-American Empire that might have been if the South had won the war. A countercultural English professor named O.B. Hardison—later director of Washington’s famed Folger Shakespeare Library, a post held by a succession of University of North Carolina legends—brought his dog to the SRO classes I took under him, pulled on a pipe that he rarely lit, and taught me most of what I remember about Spenser, Milton, Shakespeare, and how to write a sentence.

So it was a sentimental journey for me to read East of Eden: New and Recent Essays, the collection recently published by Rodopi Editions and co-edited by Henry Veggian, a current English professor at the University of North Carolina. Plus a pleasant surprise: John Steinbeck has finally made it onto the literary canon at Chapel Hill; David Laws, a SteinbeckNow.com guest blogger, provided the image of Steinbeck Country used for the cover of the book.

Henry’s introduction to the dozen essays written by various academics provides important insights into East of Eden that he expertly organizes around appropriate musical analogies. These took me back to my days in the music building at the University of North Carolina, where I confess I spent more time hanging around musicians than I did in the English department.

John Steinbeck played the piano, loved church music, and adored jazz. So did I. I was privileged to hear Dave Brubeck premiere his jazz cantata Light in the Wildnerness in the Hill Hall auditorium where I took weekly organ lessons, and I played on Sundays at the Lutheran Church across Franklin Street from the Anglo-Catholic Chapel of the Cross. Steinbeck admired the English who lived in Somerset, where he spent his happiest year with his wife Elaine in 1959. I loved my University of North Carolina Lutherans, who had no trouble singing Bach’s German when we performed a different cantata each year during Holy Week, a lively event Bach-loving Steinbeck himself would likely have enjoyed.

It was not the historical chapters that troubled them but rather the autobiographical interjections of Steinbeck’s narrator. As a result, critics argued that they might have held East of Eden in a higher esteem if John Steinbeck had not disrupted the historical-romantic narration of the Trask family with repeated autobiographical references.

But John Steinbeck never enjoyed the task of revising his writing, frequently annoyed by the suggestions emanating from agents, editors, and publishers. Most critics of his published books he considered picky parasites. East of Eden was no exception, as Henry helpfully notes in his introduction: “It was not the historical chapters that troubled them but rather the autobiographical interjections of Steinbeck’s narrator. As a result, critics argued that they might have held East of Eden in a higher esteem if John Steinbeck had not disrupted the historical-romantic narration of the Trask family with repeated autobiographical references.”

At the risk of disloyalty to the University of North Carolina, which had the sense to hire a teacher of Henry’s obvious stature to inspire students to Steinbeck as I was once inspired to Spenser, the ghost of the late O.B. Hardison compels me to point out two problems with East of Eden: New and Recent Essays—neither the fault of the book’s co-editor, who inherited the project following the death of Michael Meyer: (1) At 67.00 euro dollars, the book is too expensive for independent scholars, limiting its readership to institutional academics with stable library budgets; (2) the essays on East of Eden vary wildly in quality, type, and readability. Several are illuminating, written in clear English that rewards careful reading. Others defy comprehension, obscured by critical jargon, teutonic sentences, and usage errors that suggest translation from a language other than English.

John Steinbeck’s only specific criticism of a new novel not his own can be found in the comments he wrote about The Sergeant, a successful first novel by Dennis Murphy, the son of Steinbeck’s childhood friend and identified by some Salinians as the model for Cal Trask in East of Eden. Steinbeck’s critique of Murphy’s ending for the novel was constructive, and Murphy said he understood it. I know I’m no John Steinbeck, but my lingering loyalty to the University of North Carolina and my newly discovered respect for Henry Veggian compel me to share advice from my own experience as an editor and writer with writers, editors, and publishers of future books about John Steinbeck:

1. Writers of Articles