John Steinbeck liked to travel and learned to drive while growing up in Salinas, California, where a stretch of nearby Highway 101 was officially named for the author of Travels with Charley at an October 26 ceremony in Steinbeck’s hometown. Legislation naming the John Steinbeck Highway portion of Highway 101—from the Espinosa Road/Russell Road undercrossing to John Street in downtown Salinas—passed the California State Assembly last year as part of a bill designating other sections of Highway 101, including Gateway to the Pinnacles Highway. Appropriately, the John Steinbeck Highway sign was unveiled at the National Steinbeck Center, located on the historic Salinas, California main street accessed from Highway 101 at the “National Steinbeck Center” exit familiar to visitors since the building opened two decades ago. Said Steinbeck scholar Susan Shillinglaw, director of the busy Salinas, California center, “John Steinbeck loved cars” and owned a Packard, a Jaguar, a Buick, even a rare European car. “In nearly all of his books, cars roll along highways—including two of his best road books: Travels with Charley and The Grapes of Wrath.”

Archives for October 2015

Salinas, California Stretch of Highway 101 Named for John Steinbeck Earlier This Week

“A Home From the Sea”: Robert Louis Stevenson and The House John Steinbeck’s Friend Bruce Ariss Built with Salvage from Monterey Bay

Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.This be the verse you grave for me;

‘Here he lies where he longed to be,

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.’—Robert Louis Stevenson

A Home From the Sea

It was easy to see Monterey Bay from just about anywhere on Huckleberry Hill, and if you could see the blue of the water over the mottled roofs of Pacific Grove and Monterey then you could easily see the slow-moving tugs as they struggled through the waves towing barges of rough-cut lumber from the mills up north. The loads were destined for the lumberyards of Santa Barbara, Ventura, or maybe Los Angeles, but the only time that mattered to anyone on the Hill was when one of the tugs floundered in a storm and the restraining cables holding the lumber snapped, dumping the rich cargo into the choppy seas.

The only time that mattered to anyone on the Hill was when one of the tugs floundered in a storm and the restraining cables holding the lumber snapped, dumping the rich cargo into the choppy seas.

There was no system to alert anyone of that, just the understanding that high winds invariably led to fresh carrion being spread upon the waters of the bay and, like hungry gulls, when the storm was over they descended in their numbers onto the beaches to claim it. In crank-up Fords and Chevys, in Model-A and Studebaker pickups, they came, and in groups or alone, they came, a new kind of California coastal hunter and gatherer, scouring the beaches and hauling from the shore the salvage that the waves and the tides would deliver to their feet. Much of it was clear redwood timber cut from the massive trees that grew in profusion in the coastal forests above San Francisco: clear, sweet-smelling redwood boards perfect to build a house, a painter’s studio, or to add another room to a house already lived in.

There was no system to alert anyone, just the understanding that high winds invariably led to fresh carrion being spread upon the waters of the bay and, like hungry gulls, when the storm was over they descended in their numbers onto the beaches to claim it.

The Ariss house at the end of Lobos Street was like that, added to and built upon by Bruce and Jean over the years, constructed up and out with redwood boards gathered from the rocks near the canneries or from the wide beaches that embrace Pacific Grove. Bruce and Jean painted, but they also wrote, and when someone commented on the vast amount of building material that seemed to have gone into building so many homes on Huckleberry Hill, it was, as Bruce was wont to say, due to a perfect combination of ill wind and good fortune that had provided so many of them with shelter.

It was, as Bruce was wont to say, due to a perfect combination of ill wind and good fortune that had provided so many of them with shelter.

Apart from painting, writing and editing a monthly news magazine containing photographs, gossip, and items of interest to Monterey Bay’s fast-growing community of artists, Bruce had developed a zeal for sawing wood and pounding nails. And as the size of his family increased, one new room after another was added to his house. It had become the passion of his lifetime, friend and neighbor John Steinbeck was to say.

It had become the passion of his lifetime, friend and neighbor John Steinbeck was to say.

When Jean went into the hospital to have their fifth child, so many unwashed dishes had accumulated in the kitchen sink that Bruce, who didn’t like wasting time washing them, built a second kitchen next to the first one. And in it he added a second sink. The dishes in both were waiting for Jean when she returned home with Baby Holly. By then, Bruce had moved to the top of the house and was hammering together a box-like observation room from which he could look out over the whole of Monterey and Monterey Bay. When its construction was done, he installed a large round window and attached a salvaged ship’s wheel to the exterior. On a foggy day the house appeared to be a three-story ship negotiating its way through the towering pines.

On a foggy day Bruce and Jean’s house appeared to be a three-story ship negotiating its way through the towering pines.

From time to time John Steinbeck was there to lend a hand with a hammer, and later in the day with a jug of red wine nearby he would sit at the kitchen table to read aloud the pages he’d written that day or the day before. The house that Carol and John Steinbeck lived in was an older and much more conventional one down the hill in Pacific Grove, and it was there every morning that John, clutching a ledger book and a handful of sharpened pencils, would be led to a shed in the back garden and locked in. It had a window so he could make good an escape if necessary but, feeling that he lacked the discipline required to write, he’d made an arrangement with Carol to lock him up in the morning and let him out in the middle of the afternoon. Under those conditions he wrote The Red Pony, Tortilla Flat, In Dubious Battle, The Long Valley, and began Of Mice and Men.

The house that Carol and John Steinbeck lived in was an older and much more conventional one down the hill in Pacific Grove, and it was there every morning that John, clutching a ledger book and a handful of sharpened pencils, would be led to a shed in the back garden and locked in.

One day soon after Bruce’s cabin on the roof was finished, John and Bruce stood in the yard looking up at Bruce’s creation.

“It looks impressive to me, what do you think?” Bruce asked.

John’s eyes traveled from side to side and then up to the roof where a colorful flag of some sort flapped on a pole in a breeze coming off the bay.

“I can tell you this much,” he finally answered. “This house is an achievement over modern architecture.”

“Then maybe it’s done,” Bruce said thoughtfully.

“So, I guess it’s ‘home is the sailor, home from the sea,’” he chuckled, lifting his cup of wine in a salute, not just to his house but to Robert Louis Stevenson, who had at one time spent several months living just down the hill in Monterey working on the first draft of Treasure Island.

“No, it’s the other way around,” John said, turning to look at the sea over the rooftops. “Considering the source of your materials, in your case you should be saying, ‘Home is the sailor, his home is from the sea.’”

Meditating on Miracles and Death While Waiting at a Car Wash in Dubuque, Iowa: Poem by Roy Bentley

Miracles

There are the extraordinary few we hear of

like Joan of Arc, who, by some fluke of grace,

deciphered the message; had a constituency,

and gave back what they heard, regardless.

By the Men’s Room in Miracle Car Wash

in Dubuque, Iowa, I recall my cousin Bob

telling me he heard the audible voice of God.

By a turnstile in the Customer Waiting Area,

thinking of Bob and believers who overstate

in service to the cause of faith, I feel indebted,

recalling he risked censure to say there is more.

Still, I’m hoping they can get the dead bugs off,

wishing away a deep-buried scratch in the paint

where a bystander dreaming of earned heaven

or hell brushed against a passenger-side door.

I’ve been to Ohio to bury Bob who has died,

a last pronouncement that he needed to sleep

for a while. Maybe the best reason to believe

is vacuuming the interior floor of my Toyota:

the owner hires parolees and convicted felons

in service to minimum-wage second chances.

I’m thinking you have to hand it to Iowans:

with or without miracles, they get it done.

A warm, sudsy water gushes over my car

identifiable by Obama-Biden messaging

against the sea of McCain-Palin decals.

It’s as if I’m in attendance at a funeral,

Bob’s, though I recall grief is like that

and reshapes the interior self for years.

I sentinel the forced-air dryer beading

a runoff from the rinse-dry cycle, hear

Bob reminding me he sold everything

and relocated to Springfield, Missouri

on orders of vocal sounds answering,

through machine hum and grim gray,

a need to be bright silver for a while.

“This Old House” Means Conservation—and Care for Art and Ecology—in John Steinbeck’s Pacific Grove

Pacific Grove, California—John Steinbeck’s retreat when there was writing or healing to be done—is a preservation-minded community where “this old house” means the whole town, and residents like Nancy and Steve Hauk, celebrity-citizens with ties to Steinbeck, contribute to the present while connecting with the past. Founded in 1875 as a seaside getaway for camp-meeting Methodists, one where liquor was outlawed and modesty was mandated, Pacific Grove soon became a summer destination—Chautauqua West—for vacationing non-Methodists from inland towns such as Salinas.

Founded in 1875 as a seaside getaway for camp-meeting Methodists, one where liquor was outlawed and modesty was mandated, Pacific Grove soon became a summer destination—Chautauqua West—for vacationing non-Methodists from inland towns such as Salinas.

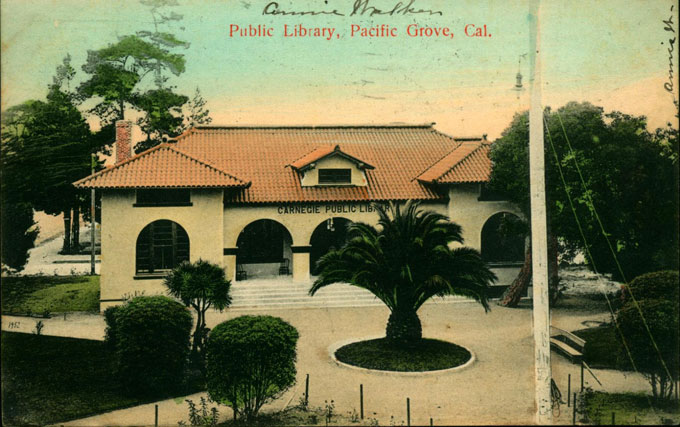

Steinbeck’s parents liked Pacific Grove’s culture and cool air; their modest weekend cottage off Central Avenue on 11th Street had a view of the bay when Steinbeck was a boy. In 1906 Pacific Grove got a grant to build a Carnegie library on Central, within walking distance of the Steinbeck cottage, where Steinbeck’s wife Carol Henning is thought to have worked in the early 1930s. Steinbeck’s friend Ed Ricketts lived in a handsome house up the hill from Central Avenue on Lighthouse, the other major thoroughfare—until Ed’s wife left him and he moved to lab space he rented for his struggling marine specimen business between Lighthouse and Central avenues. Now located on busy Cannery Row, where peaceful Pacific Grove meets fun-loving Monterey, “Doc’s Lab” attracted legendary people and parties in the 1930s and 40s, achieving the stature of myth in John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row fiction.

Nancy Hauk, an artist, and Steve Hauk, a writer, own the Ricketts home today. Together they operate Hauk Fine Arts, an intimate art gallery less than a block from Holman’s Department Store, another Pacific Grove landmark made famous by Steinbeck’s fiction. A playwright, Steve recently completed “Almost True Stories from a Writer’s Life,” a series of short stories based on relationships and events from Steinbeck’s life in Pacific Grove, Monterey, and Salinas. One story, “The Daughter,” is set in the Ricketts house. Another features Bruce and Jean Ariss, artists who lived in Pacific Grove during Steinbeck’s time and moved in the colorful Ricketts-Steinbeck circle. Steve is an expert on California artists, and the gallery features paintings by friends of Steinbeck, including Bruce Ariss, inspired by the life and landscape of Pacific Grove, Carmel, and Monterey Bay. Visitors to Hauk Fine Arts who are willing to take up the time freely given by Steve, a former reporter for the Monterey Herald, get an instant education in Steinbeck, Pacific Grove, and the town’s this-old-house history.

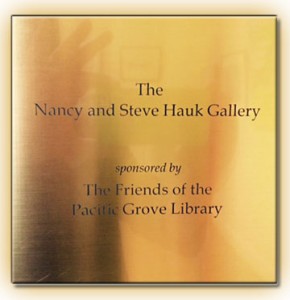

Pacific Grove Library Honors Hauks with an Art Gallery

The Hauks love Pacific Grove, and Pacific Grove loves them in return. Earlier this year officials announced that new gallery space in the Pacific Grove Public Library would be named in honor of the couple, a tribute to Nancy’s art and Steve’s devotion to his wife, who suffers from a progressive neurological disease. Friends of the Library, a volunteer group that gets things done, raised funds to build out the space, part of a long-term program to upgrade and restore the aging Carnegie library to its former glory. Located a stone’s throw from the sea in a neighborhood of immaculate Victorian homes and historic public buildings including Chautauqua Hall, the library was and is a gathering place for Pacific Grove, where culture continues to attract visitors like butterflies. An art exhibit and lecture series celebrating Rachel Carson’s 1955 book about coastal ecology, The Edge of the Sea, will feature the Carson and Steinbeck biographer William Souder on December 4.

The Hauks love Pacific Grove, and Pacific Grove loves them in return. Earlier this year officials announced that new gallery space in the Pacific Grove Public Library would be named in honor of the couple, a tribute to Nancy’s art and Steve’s devotion to his wife, who suffers from a progressive neurological disease. Friends of the Library, a volunteer group that gets things done, raised funds to build out the space, part of a long-term program to upgrade and restore the aging Carnegie library to its former glory. Located a stone’s throw from the sea in a neighborhood of immaculate Victorian homes and historic public buildings including Chautauqua Hall, the library was and is a gathering place for Pacific Grove, where culture continues to attract visitors like butterflies. An art exhibit and lecture series celebrating Rachel Carson’s 1955 book about coastal ecology, The Edge of the Sea, will feature the Carson and Steinbeck biographer William Souder on December 4.

Located a stone’s throw from the sea in a neighborhood of immaculate Victorian homes and historic public buildings including Chautauqua Hall, the library was and is a gathering place for Pacific Grove, where culture continues to attract visitors like butterflies.

The Nancy and Steve Hauk Gallery formally opened at a Friends of the Library reception—attended by fellow artists and community members, and the Hauks’ younger daughter Anne—on October 2, 2015. The library’s Rachel Carson exhibit opened the same day, a meaningful coincidence on many levels. The Methodists who founded Pacific Grove may have been teetotalers, but they were thirsty for knowledge and curious about ideas, art, and science, subjects that defined the summer Chautauqua circuit with its West Coast center in Pacific Grove more than a century ago.

The Nancy and Steve Hauk Gallery formally opened at a Friends of the Library reception—attended by fellow artists and community members, and the Hauks’ younger daughter Anne—on October 2, 2015. The library’s Rachel Carson exhibit opened the same day, a meaningful coincidence on many levels. The Methodists who founded Pacific Grove may have been teetotalers, but they were thirsty for knowledge and curious about ideas, art, and science, subjects that defined the summer Chautauqua circuit with its West Coast center in Pacific Grove more than a century ago.

The Methodists who founded Pacific Grove may have been teetotalers, but they were thirsty for knowledge and curious about ideas, art, and science, subjects that defined the summer Chautauqua circuit with its West Coast center in Pacific Grove more than a century ago.

Like Ed Ricketts, Rachel Carson was a scientist; like Ricketts and Steinbeck, she thought deeply and wrote prophetically about ecology. The Sea Around Us (1950), The Edge of the Sea, and Silent Spring (1962), popular books that have become classics, equal Steinbeck in style and Ricketts in observation. Nancy Hauk paints with similar grace and perception about similar subjects—seabirds on the sand, water reeds reflected in a tide pool, the gentle golden hills described by Steinbeck in his best writing about California. Like Steinbeck, Nancy rarely repeats herself in her work, and Steve is still finding sketches and paintings—some completed, others left unfinished—in their house on Lighthouse Avenue.

A Piece of This-Old-House from Steinbeck’s Pacific Grove

Nancy and Steve are walkers in a walking town. Since Nancy’s move to memory care at Cottages of Carmel, where she often can be found with caregiver and friend Yolanda Campos, Steve’s been doing more driving than walking, daily making the drive to visit Nancy over Carmel Hill, a trip Mac and the Boys made to hunt frogs in Cannery Row. One day recently he walked by the Steinbeck family cottage off Central Avenue in Pacific Grove and noticed a dumpster loaded with wood that had been removed for replacement in the process of retrofitting the cottage. “This old house,” he said, “witnessed so much history, and writing. I salvaged three pieces of redwood siding from the dumpster, just in case. I’m glad I did. When I drove by the next day the dumpster was gone.” Thanks to Steve’s care for John Steinbeck, Pacific Grove, and posterity, a piece of the famous cottage has joined the collection of Steinbeck memorabilia at the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies, one that includes Steinbeck’s typewriter and the manuscripts of books the author wrote while living—and healing—in the place he loved.

Nancy and Steve are walkers in a walking town. Since Nancy’s move to memory care at Cottages of Carmel, where she often can be found with caregiver and friend Yolanda Campos, Steve’s been doing more driving than walking, daily making the drive to visit Nancy over Carmel Hill, a trip Mac and the Boys made to hunt frogs in Cannery Row. One day recently he walked by the Steinbeck family cottage off Central Avenue in Pacific Grove and noticed a dumpster loaded with wood that had been removed for replacement in the process of retrofitting the cottage. “This old house,” he said, “witnessed so much history, and writing. I salvaged three pieces of redwood siding from the dumpster, just in case. I’m glad I did. When I drove by the next day the dumpster was gone.” Thanks to Steve’s care for John Steinbeck, Pacific Grove, and posterity, a piece of the famous cottage has joined the collection of Steinbeck memorabilia at the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies, one that includes Steinbeck’s typewriter and the manuscripts of books the author wrote while living—and healing—in the place he loved.

Photo of Ricketts-Hauk home in Pacific Grove courtesy David Laws.

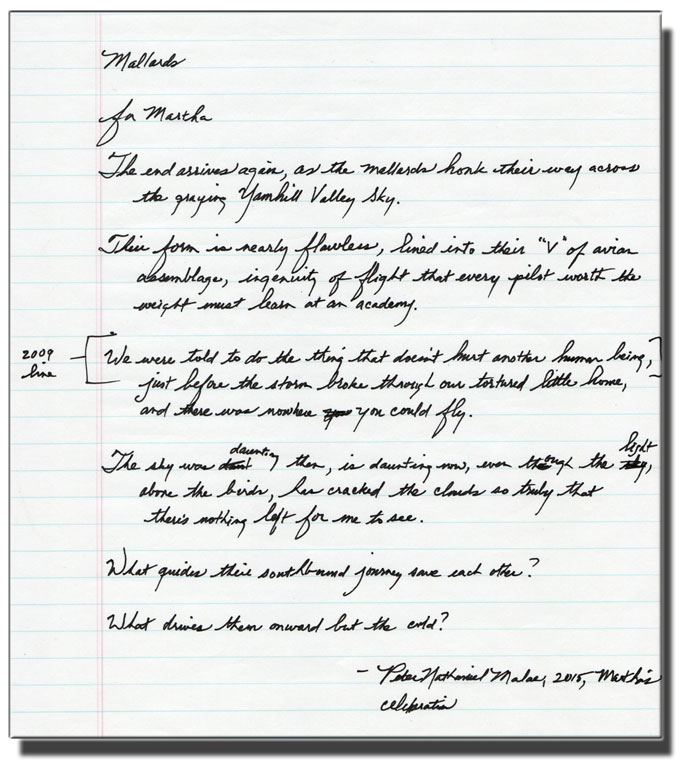

In Memoriam, Martha Heasley Martha Cox: Lyric Poem by Peter Nathaniel Malae

Mallards

The end arrives again, as the mallards honk their way across the graying Yamhill Valley sky.

Their form is nearly flawless, lined into their “V” of avian assemblage, ingenuity of flight that every pilot worth the weight must learn at an academy.

It’s rare to witness grace, it’s rarer still to have some inner bearings where the grace is processed right, it’s rarest to look inward.

We were told to do the thing that doesn’t hurt another human being, just before the storm broke through our tortured little home, and there was nowhere you could fly.

The sky was daunting then, is daunting now, even though the light, above the birds, has cracked the clouds so truly that there’s nothing left for me to see.

What guides their southbound journey save each other?

What drives them onward but the cold?

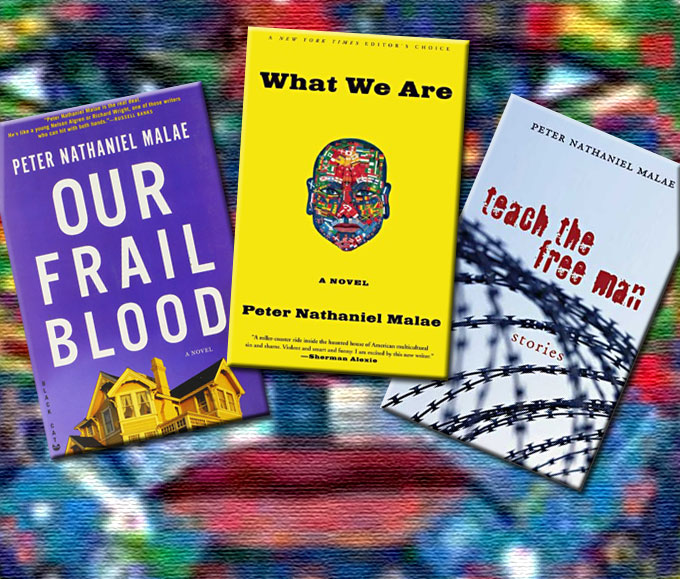

“Our Story Is a Life and Death Thing”: Peter Nathaniel Malae on Reading John Steinbeck and Writing American Literature

Like John Steinbeck, the American writer Peter Nathaniel Malae is a rugged realist who insists on honesty. A former Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose State University who grew up in San Jose and nearby Santa Clara, California, Malae spoke candidly about John Steinbeck, American literature, and the life-and-death issues of writing for a living the day after he eulogized Martha Heasley Cox. The memorial event was held in her honor by the Steinbeck studies center she founded at San Jose State University in 1971.

“That Book Saved Me”: On Reading John Steinbeck

Malae was an inspired choice to represent the 36 creative writers who received Steinbeck Fellow stipends. Teach the Free Man, a collection of Malae’s stories, was published in 2007, the year he was named a Steinbeck Fellow. Two novels published since then—What We Are (2010) and Our Frail Blood (2013)—confirmed Malae’s reputation as a versatile writer who refuses to repeat himself. Like Steinbeck at a similar point in his career, Malae’s output is ambitious: he has already written two more novels, a second collection of stories, two collections of poetry, and a play with a philosophical theme reminiscent of Steinbeck.

Like Steinbeck at a similar point in his career, Malae’s output is ambitious: he has already written two more novels, a second collection of stories, two collections of poetry, and a play with a philosophical theme reminiscent of Steinbeck.

The son of an Italian-American mother and a Samoan father, Malae spent his childhood in a culturally diverse, working-class neighborhood of Santa Clara, squeezed between the city’s “drug-dealing hub”—Royal Court Apartments, Warburton Park, and Monroe Apartments—and the stretch of El Camino Real known as Little Korea for its string of three dozen Korean restaurants and grocery stores running interminably from Santa Clara to Sunnyvale. As a boy, he utilized public transportation on the bus line 22, a tradition kept later as a writer, where he’d composed the bulk of his novel, What We Are, during three-hour rides on the 522, between East Palo Alto and Eastridge Mall in East San Jose.

As a boy, he utilized public transportation on the bus line 22, a tradition kept later as a writer, where he’d composed the bulk of his novel, What We Are, during three-hour rides.

Malae’s father served three decorated combat tours as a tracker with the Special Forces in Vietnam. His uncle Faulalogofie, a Force Recon Marine who’d also fought in Vietnam, was killed by police in Pacifica, California in 1976. His grandfather—the first Samoan minister in America—was a veteran of the Korean Conflict. “I was raised by men who’d had a gang of life-and-death pain in their lives,” Malae says. “But even before they’d ever gone off to war, they’d suffered tremendously. Death, poverty, choicelessness. A weird multigenerational effect of it all is that they basically taught me what to go for in story: they were literary in contradiction. A lot of anger, a lot of third-world violence, yeah, but a lot of third-world beauty, too, a gang of forgiveness.”

‘I was raised by men who’d had a gang of life-and-death pain in their lives,’ Malae says.

Malae attended an exclusive Catholic prep school in San Jose where, like John Steinbeck as a young man, he absorbed the language and rhythm of religious ritual. He read through the Bible for the first time and had his first encounter with Steinbeck in a freshman English composition class. “I loved Tom Joad,” Malae said, “the way he stood up for his family, the way he took it because there was no choice but to take it. I could relate to him. I never told anyone in high school, but I sort of secretly rooted for farmers back then on the sole strength of that image where the tractor comes in and topples the Joad farm.”

‘I loved Tom Joad,’ Malae said, ‘the way he stood up for his family, the way he took it because there was no choice but to take it. I could relate to him.’

Malae went on to play football and rugby at Santa Clara University and Cal Poly, but began getting into serious trouble with the law, having been arrested more than eight times for assault and battery in a two-year span, twice resulting in serious injury. “I was very angry back then. I fought everyone, anyone. Didn’t care how many people I had to fight, didn’t care what the outcome would be. When it comes to growing up tough and angry, I don’t defer to anyone, really. You own it, of course, how you are, but you also became it, shaped by the forces around you.” Within a few years, Malae found himself at San Quentin, where he (again) read through the Bible and started writing 500 words a day—copying Hemingway—on scraps of paper and whatever else was available. “I wrote on the walls, man. I wrote on my arms. The soles of my slippers, as Frost prescribed.”

Today Malae writes with a computer, but still revises in longhand, as seen in the manuscript of “Mallards,” the poem he composed in honor of Martha Cox. He thinks that Steinbeck, a pencil-lover who eventually adapted to the typewriter, would like the cut-and-paste convenience of computers. But he dislikes social media, email, and texting, inventions that he says increase social isolation and divorce users from life-and-death reality. On the train to San Jose he worked on a new novel, observing “human beings in their essence and element,” akin to Steinbeck’s claim of being a shameless magpie, taking to the fields with paisanos.

On the train to San Jose he worked on a new novel, observing ‘human beings in their essence and element,’ akin to Steinbeck’s claim of being a shameless magpie, taking to the fields with paisanos.

In prison Malae discovered The Pastures of Heaven, which he’d read in Spanish (Las Pasturas del Cielo). He described the experience with Steinbeckian irony in “The Book is Heavenly,” an award-winning essay published in South Dakota Review (Vol. 41, No. 1 and 2):

The book became my paperback talisman of hope. Something I could rely on in the unreliable undercurrent of prison life. . . . On the Catholic calendar distributed to us during Christmas, my reading list for the months of March, April and May 1999 were: The Catch-Me Killer, Bob Erler, and then fourteen straight readings of The Pastures of Heaven, John Steinbeck. . . . It kept me sharp and focused, reminded me of what once was and what, of course, could be again. That book saved me.

“Realism in the Craft”: On Writing American Literature

Malae’s first novel, What We Are (the title comes from a quatrain by Byron), explores life and death in the dark corners of contemporary society that few writers of American literature have exposed with comparable sharpness or skill. The narrative is a journey of adjustment, to anomie and estrangement, by a sensitive, angry character who learns, as Malae himself believes, that “our story is a life and death thing.” Our Frail Blood, his second novel (the title comes from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night), is as different from What We Are as East of Eden is from Cannery Row. In alternating plot lines, the book encompasses three generations of California life in which children and grandchildren pay for the secret sins of fathers, brothers, and sons. The family epic unfolds through the eyes and actions of fully developed female characters who bring unity, resolution, and redemption to the story, like Steinbeck’s women in The Grapes of Wrath. Malae cites East of Eden, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and Francis Ford Copolla’s Godfather II as narrative forebears in scope and theme.

The narrative of Malae’s first novel is a journey of adjustment, to anomie and estrangement, by a sensitive, angry character who learns, as Malae himself believes, that ‘our story is a life and death thing.’

The Question, Malae’s most recent work, is his foray into the world of theater. The story dramatizes the struggle of a Hispanic ex-boxer and convict to answer the existential question asked by his eight-year-old son: “Why do people kill other people?” Malae says the idea for the play—and the question it poses—occurred to him at San Quentin in 1999, when Manuel “Manny” Babbitt, a veteran of the Vietnam War with a Purple Heart for heroism, was executed. Babbitt, a Marine, was wounded at the Battle of Khe Sanh in 1968; he received the death sentence in 1980, before post-traumatic stress disorder was understood as a consequence of contemporary warfare. Manny Babbitt’s last words were “I forgive you all”; at the end of The Question, Malae’s character tells his son that he can’t say why people kill other people—but “I know why people save other people.”

Malae says the idea for his play—and the question it poses—occurred to him at San Quentin in 1999, when Manuel ‘Manny’ Babbitt, a veteran of the Vietnam War with a Purple Heart for heroism, was executed.

Intense, thoughtful, and articulate, Malae worries about the overpopulation of modern American literature by writers trained in college MFA programs, 360 in number at last count. “They teach writers that the creation of story is a democratic roundtable or assembly line. Which can eradicate the soul of the work. Since art is about desperation, the last thing you want infecting your work is conformity. And then as you pay a fee for a service, the natural tendency is to expect that you get what you paid for. The daily struggle with the craft doesn’t abide that ethic. Sometimes it barely abides you. Sometimes you get nothing.” Steinbeck, too, championed what Malae calls “realism in the craft” forged by fierce aesthetic individualism.

Steinbeck, too, championed what Malae calls ‘realism in the craft’ forged by fierce aesthetic individualism.

Malae described the connection he feels with American literature of John Steinbeck’s century in an interview with Oregon Literary Arts after winning the drama fellowship for The Question:

I’m with O’Connor and Faulkner and a whole horde of other dead masters who describe the deal in terms of a blue-collar work ethic. I see the creative process as merely this, a dress-down of self that more or less occurs daily: do you have the balls to call yourself a “writer”? Well, then, “put the posterior in the chair,” as my freshman comp teacher used to say; “don’t talk,” as Hemingway advised, and handle your business.

Paul Douglass, the San Jose State University English professor who managed the Steinbeck Fellows program from 2000 to 2013, notes that Malae’s 2007-2008 class was “outstanding.” He recalls reading the untitled manuscript of What We Are when Malae’s name was first submitted, and being impressed. After finishing his fellowship, Malae continued to correspond with Martha Cox, a shrewd reader and enthusiastic patron. In his remarks at her memorial he recalled visiting her modest San Francisco apartment, crowded with “classics of American literature” by some of his favorite authors. He was humbled, he said, to see a copy of Teach the Free Man, read and annotated, on her shelf.

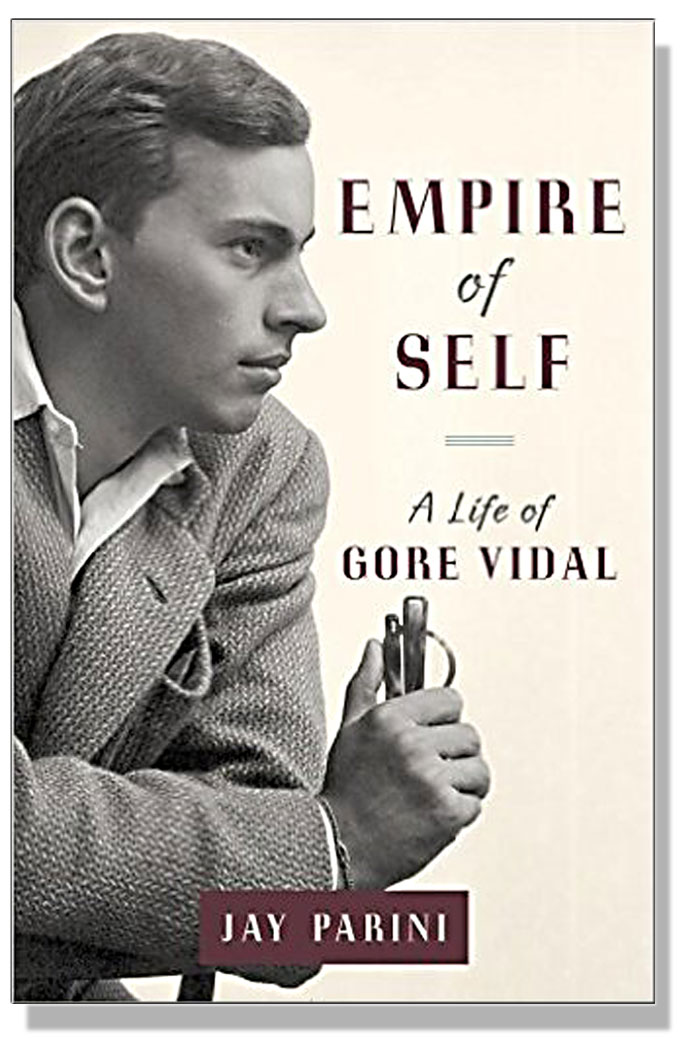

John Steinbeck Biographer Writes Life of Gore Vidal, Master of Historical Fiction

Though they were born a generation apart on opposite coasts, John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal—bestselling writers with close ties to Broadway, Hollywood, and progressive politics—had much in common. Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal, by John Steinbeck’s versatile biographer Jay Parini, considers the controversial author of Lincoln, Burr, and Myra Breckinridge to be a master of historical fiction, a literary form that didn’t fit Steinbeck but suited Vidal, who renewed its energy and spawned a generation of imitators. Axinn Professor of English at Middlebury College and a poet-novelist-critic who understands what creative writers endure for their craft, Parini suits Vidal particularly well as a biographer. Like John Steinbeck: A Life (1995), his life of Gore Vidal provides a contemporary writer’s perspective on a controversial literary career, with an advantage not shared by biographers of Steinbeck. Parini and Vidal were friends until Vidal’s death in 2012, and Parini had frequent conversations with his fascinating subject, who gave him free access to Vidal’s extraordinary circle of friends, associates, and yes, enemies.

Jay Parini, John Steinbeck, and the Case for Gore Vidal

The result of that fortunate relationship is a compelling chronicle—detailed in research, comprehensive in scope, and convincing in its case for Gore Vidal as a 20th century writer who, like John Steinbeck, is worth reading in the 21st. Describing himself as Vidal’s Boswell, Parini views his volatile subject with the empathy of a colleague and the wonder of a disciple, forgiving without judging, or ignoring, the master’s faults. This is an advisable stance for any biographer, but it serves Gore Vidal’s peculiar personality and expansive sense of self particularly well. John Steinbeck was a shy man with a domestic situation that made research and publication difficult for biographers following his death in 1968. Vidal, who admired Steinbeck and served as a source for Parini’s Steinbeck biography, avoided this danger by admonishing Parini to note the potholes but keep in his eye on the road when writing the biography that Vidal made Parini promise he would finish when Vidal was gone.

Parini views his subject with the empathy of a colleague and the wonder of a disciple, forgiving without judging, or ignoring, the master’s faults.

A gentle sort without Vidal’s sharp edges, Parini kept the bargain, filling in the self-narrative begun by Vidal in the novels Vidal wrote in his 20s, in essays and interviews and plays over a period of six decades, and in a pair of provocative memoirs that leave no prisoners. As suggested by the title Parini chose for his biography of this great-but-not-good man, Vidal’s story fascinates because it records the self-invention of a born storyteller who wrote prodigiously, characterized non-historical fiction like Myra Breckinridge as “inventions,” and considered bitchiness and versatility to be evidence of talent. He was as competitive with writers as we was in sex, and he fought publicly with colleagues who crossed or criticized him. He attacked Truman Capote, a soft enemy, and made scenes with Norman Mailer, a tougher target. He suggested that John Steinbeck, who avoided snits with other writers, was a bit of a one-note: “He “didn’t ‘invent’ things,” Vidal said of Steinbeck. “He ‘found’ them.”

Gore Vidal and John Steinbeck: Two Lives in Letters

Like Samuel Johnson, John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal were thin-skinned, temperamental men with mother issues. Both felt sorry for their fathers and identified with their fathers’ fathers, stronger figures, in their writing. Steinbeck compensated for self-doubt by avoiding public appearances and entangling private alliances beyond a loyal circle of friends, collaborators, and relatives. “Your only weapon,” he advised a young writer whose father was a boyhood friend, “is your work.” Vidal, a domineering narcissist, adopted the opposite strategy, creating a public persona built around conflict, desire, and adulation. Work was one weapon. So was a personality that, as Jay Parini observes, others could love or leave but never outrun. Steinbeck was a turtle. Vidal was a hare.

John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal were thin-skinned, temperamental men with mother issues. Steinbeck was a turtle. Vidal was a hare.

Reared in a rural California town where the Republican Party ruled and the Episcopal church was a center of social life, John Steinbeck got off to a slow start as a writer. Cup of Gold, his first novel, fails as historical fiction about a far-off time and place; an early attempt at mythic allegory, To a God Unknown, succeeds only because it is rooted in familiar soil. He finally found his voice in three novels, written during the Great Depression, about America’s rural underclass: ranch hands and farm workers in California, migrant sharecroppers from Oklahoma. He lived in small houses and wrote in small rooms and never forgot what it was like to go without; he feared success, and and he was right. A New Deal Democrat, he wrote political speeches but refused to make them. As with Gore Vidal, alcohol was a social lubricant, but to opposite effect. Vidal performed in company. Steinbeck looked and listened. Steinbeck liked working people, preferably farmers, and, like Faulkner, he lived part-time in the past. So did Vidal, of course, but his past was imagined rather than remembered.

Vidal performed in company. Steinbeck looked and listened. He liked working people, preferably farmers, and lived part-time in the past.

Vidal was born in Washington during the administration of Calvin Coolidge and spent his happiest times at the Rock Creek Park home of his blind grandfather T.P. Gore of Mississippi, elected U.S. Senator from Oklahoma when Oklahoma became a state. Vidal’s roots were Deep South (Al Gore is a distant relative), but his social centers as a boy were Capitol Hill, New York, and the mansions of his grandfather and his mother’s second husband, Hugh Auchincloss, a millionaire who later married the mother of Jackie Kennedy. Like Steinbeck, Vidal was christened as an Episcopalian, but he attended St. Albans, an exclusive academy run by the Episcopal Church, rather than public school. He fell in love with a classmate, and both enlisted at age 18. The boy he loved was killed in combat and, as Parini suggests, left a hole in Vidal’s heart that lasted for a lifetime.

Like Steinbeck, Vidal was christened as an Episcopalian, but he attended St. Albans, an exclusive academy run by the Episcopal Church, rather than public school.

He disliked his mother, liked his father’s girlfriends, and imbibed the Dixiecrat politics of his Grandfather Gore, which were to the right of the Steinbeck family’s progressive California Republicanism. Parini describes the anti-New Deal bias Senator Gore shared with Dixiecrat allies like Huey Long as “Tory populism”: anti-corporate, anti-war, and anti-statist, anti-values that defined Vidal’s vision of America as a Republic gone bad, like Rome, in his political essays, his historical fiction, and his campaigns for public office, first as candidate for Congress from New York, later for Governor of California. If Vidal read The Grapes of Wrath to Senator Gore as a teenager, a distinct possibility, the old man probably reacted like his fellow Oklahoman, Lyle Boren, who denounced Steinbeck’s depiction of Oklahoma from the floor of the U.S. House: with denial and disdain. Vidal’s view of America as a child was that of his grandfather’s political class: nativist, isolationist, and distrustful of Wilsonian-Rooseveltian democracy. His ambitions as an adult, like his homes on the Hudson and in Italy, were imperial.

Vidal’s view of America as a child was nativist, isolationist, and distrustful of democracy. His ambitions as an adult, like his homes on the Hudson and in Italy, were imperial.

Parini records the first time Steinbeck and Vidal met, on May 8, 1955, at a Manhattan party given by the producer Martin Manulis following the TV broadcast of Visit to a Small Planet, Vidal’s satirical comedy about Cold War paranoia and gone-mad McCarthyism. Vidal’s sci-fi caricature of mid-America invaded by aliens eventually ran on Broadway and has since been revived. When Vidal met Steinbeck at the Manulis party, Steinbeck would have been involved in staging Pipe Dream, the musical adaptation of Steinbeck’s novel Sweet Thursday by Rodgers and Hammerstein that closed within months after opening later in 1955. Steinbeck’s wife Elaine, also present at the party, was a stage manager for the 1940s hit musical Oklahoma! and had a good eye. She remembered the 30-year-old Vidal as “a tense, smart, glittering young man” who shared Steinbeck’s “passion for politics” and got along with her husband. The two men shared a special affection for Eleanor Roosevelt and an admiration for Adlai Stevenson, neither of which would have appealed to their families back home.

Steinbeck and Vidal shared a special affection for Eleanor Roosevelt and an admiration for Adlai Stevenson, neither of which would have appealed to their families back home.

Vidal also felt an affinity for Steinbeck as an artist, noting to Parini that both authors had the ability to write narrative and dramatic works that people liked. Vidal said he envied Steinbeck’s “happy relation to Hollywood,” where Steinbeck’s work “adapted well” and “was treated with respect,” unlike his own. He observed, accurately, that the film East of Eden “brought Steinbeck to more people’s attention than a novel could have ever done.” And though both writers feared that television “spelled the end of the novel,” their most popular works in novel form have also proved to be their most enduring: The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, Cannery Row, and East of Eden for Steinbeck; Burr, Lincoln, and other historical fiction of American Empire for Vidal. Of the book critics who were irritated by Steinbeck’s persistent popularity, Vidal observed, “they could never forgive Steinbeck for saying things that people wanted, or needed, to hear.” As Empire of Self shows, the same can be said of Gore Vidal.