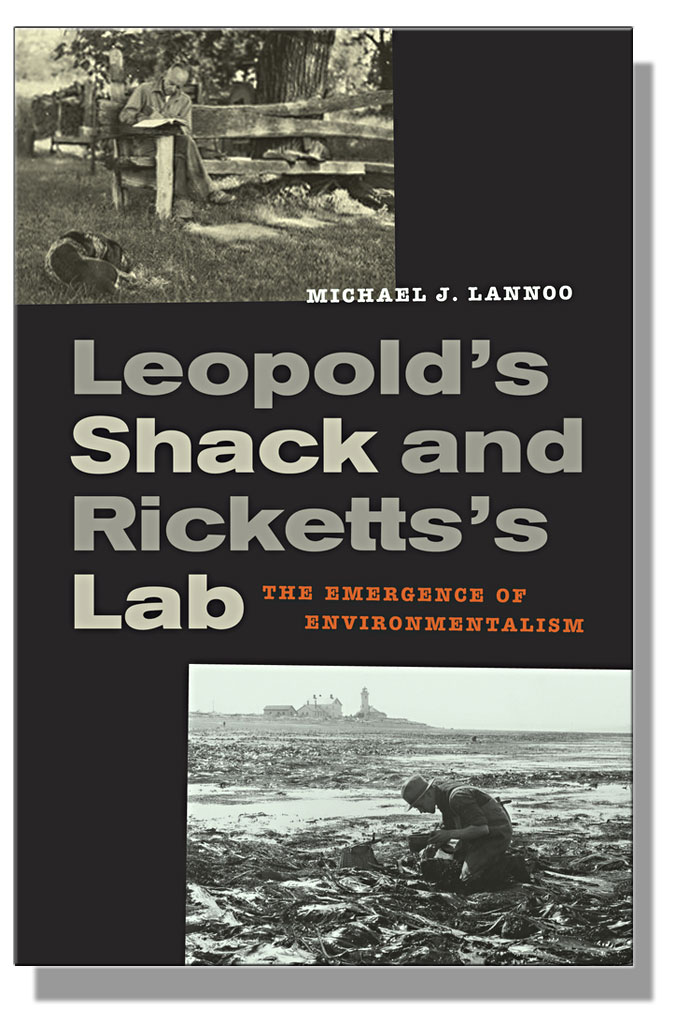

A bright, breezy book timed for the 75th anniversary of Ricketts and Steinbeck’s famous expedition to the Sea of Cortez traces today’s environmental movement and the modern field of conservation biology to two prophets born ahead of their time, 10 years and 200 miles apart, more than a century ago. As Michael J. Lannoo dramatically demonstrates in Leopold’s Shack and Ricketts’s Lab: The Emergence of Environmentalism, Aldo Leopold and Ed Ricketts approached wildlife biology, marine biology, and the earth’s ecology in a whole new way, the result of intimate observation, original thinking, and lively conversation at Ricketts’s lab on Cannery Row and Leopold’s shack on reclaimed farmland in Wisconsin—apt metaphors for the sociable minds of two unconventional scientists whose parallel paths never crossed.

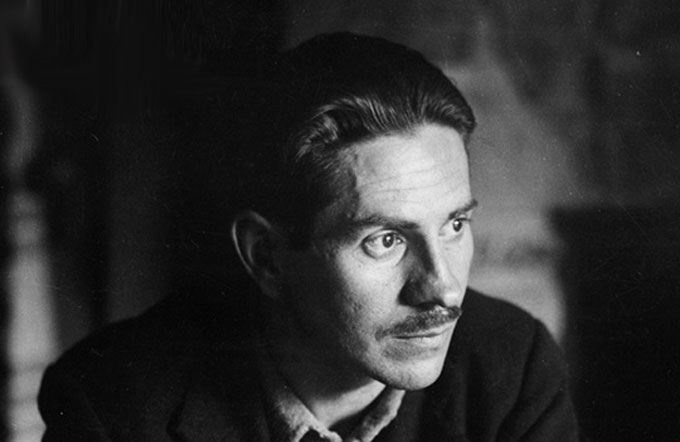

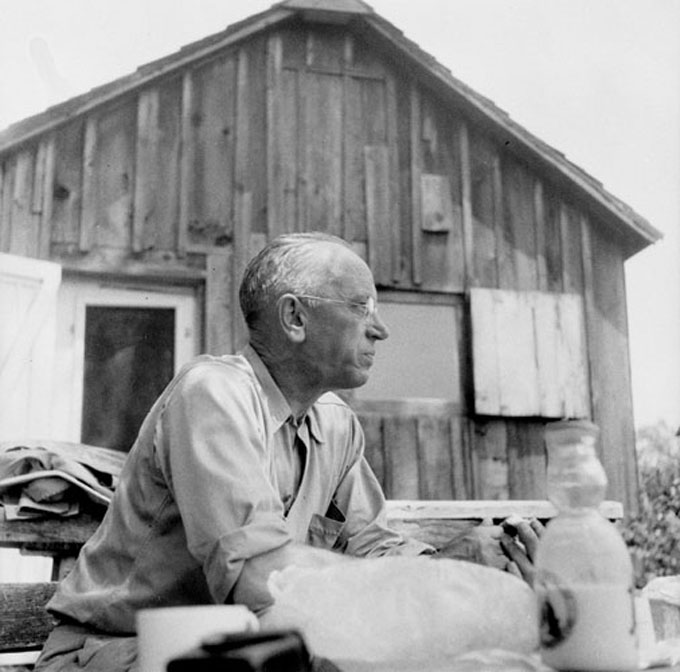

The story of Ricketts, marine biology, and the 1940 collecting expedition to the Sea of Cortez is familiar territory for Steinbeck fans and “Ed Heads,” the ardent admirers who consider Doc’s lab a shrine, like Lourdes. A less familiar narrative, equally fateful, was unfolding in the woods of Wisconsin during the same period, the 1930s and 40s, in the shack and mind of Aldo Leopold, the father of professional wildlife biology and author of Sand County Almanac (1949). Like Sea of Cortez, Leopold’s classic took time to gain steam; like Ricketts, Leopold died too soon to see his ideas change the course of science, land management, and the way we think.

Leopold died of a heart attack on the Wisconsin land he loved in 1948, months before the book that made him an environmental-movement hero was published. Two weeks later Ricketts was also dead, the result of injuries sustained when his car struck a train near his Cannery Row lab. Leopold, 10 years Ricketts’s senior, never met the transplanted Chicago native who made Cannery Row famous, in fiction and in fact. But Ricketts’s mystical thinking about marine biology eventually converged with Leopold’s ethic of wildlife biology to create the field of conservation biology and the holistic vision of today’s environmental movement, a benign way of living with nature minus the impulse to over-farm, over-fish, over-build, and over-populate. Like Steinbeck, Leopold was angered by urban sprawl and consumer waste. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts, he thought science was a saner faith than religion.

Ricketts’s mystical thinking about marine biology eventually converged with Leopold’s ethic of wildlife biology to create the field of conservation biology and the holistic vision of today’s environmental movement.

Leopold and Ricketts, opposites types in personality and behavior, come to life like the parallel protagonists of a Steinbeck novel in Lannoo’s elegant little book. Like all prophets, both men had their problems with power. Though Leopold’s 1933 work on game management became the standard textbook of its time, Sand County Almanac was passed over by publishers who doubted the commercial value of any collection of essays about nature not named Walden. Ricketts’s Between Pacific Tides (1939) eventually become a standard text for teaching marine biology, but not before it was rejected, accepted with edits, then endlessly delayed by Stanford University, its publisher. As for Sea of Cortez, does anyone think Viking Press would have touched that book without John Steinbeck’s name on the byline over “E.F. Ricketts”? True, Steinbeck mourned Ricketts’s death, but he later agreed to republish Sea of Cortez, with an essay “About Ed Ricketts” but without Ricketts’s name as co-author.

Leopold and Ricketts, opposites types in personality and behavior, come to life like the parallel protagonists of a Steinbeck novel in Lannoo’s elegant little book.

Fortunately, Michael Lannoo—a practicing scientist and popular writer about conservation biology—ignores this shameful incident, and other fetishes of what one wag calls the modern Steinbeck-studies industrial complex. Instead, he concentrates on the lives and science of his told-in-tandem subjects without the literary baggage that weighs down books about the anxiety of influence and the pleasures of symmetry by professors of English. He wisely lets Leopold and Ricketts stand on their own, unfolding their parallel stories in alternating chapters with Steinbeckian skill. Robert DeMott, the scholar and fly-fisherman who turned me on to this little gem, accurately describes Lannoo’s book as “blessedly free of cant, jargon, or technical obfuscation.” Read it and rejoice, but hear its message. Like Ricketts (who quit college) and Leopold (who went to forestry school), you don’t need a PhD to enjoy the exciting story or get the scary point. The disappearance of frogs and other species, Lannoo’s primary interest, is our generation’s Dust Bowl—“the defining event,” as Lannoo reminds us, “that made ecology suddenly relevant.”

I continue to learn a great deal about John Steinbeck through this site, Will Ray. What a terrific resource! My thanks, always, for my continuing education.

Roy

Thanks to STEINBECKNOW, Leopold’s Shack and Ricketts’ Lab gets more light and a new citation for the emerging recognition of Ed Ricketts and Aldo Leopold and their paradigm changing impact on natural science as America’s two greatest scientific naturalists. Michael Lanoo’s book is a must for the shelf of all Ed Ricketts believers (“Ed Heads”) and a clear new connection to the parallel work of Aldo Leopold as his wildlife biology bookend. Glad to see this book creep into wider Steinbeck awareness.

Not sure which generation you are referring to, but these two giants are before some people’s time. Ecology and the Preservation of wild places have been important for the last few generations at least, maybe even before Leopold and Ricketts, many going back to John Muir and the founding of The Sierra Club. Nice to see The Movement getting attention again here. I think there are Environmentalists for all sort now, especially for centrists. The Environmental Movement became a lot more popular since with Rachel Carson and Silent Spring. There are many new voices now. Sadly we seem to be Conservationists now instead of Preservationists.