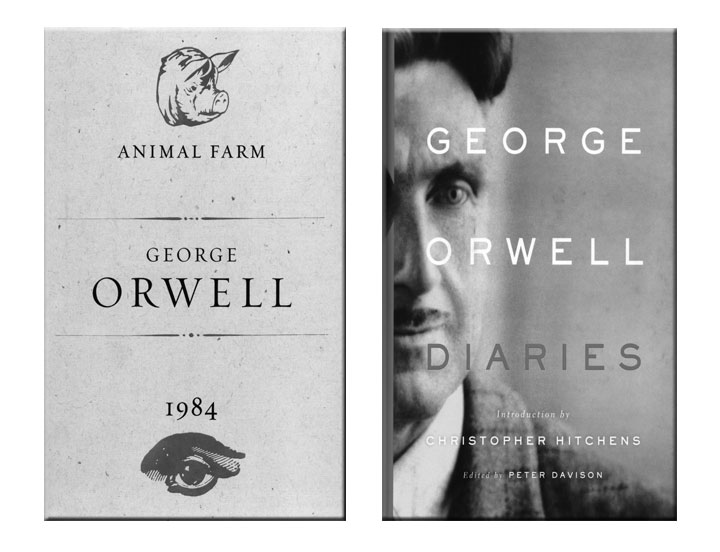

Three books published between 1945 and 1949—George Orwell’s twin tales of totalitarian tyranny, Animal Farm and 1984, and John Steinbeck’s collaboration with Robert Capa, A Russian Journal—help explain why Orwell accused Steinbeck of being a “crypto-communist” in 1948. Orwell’s caustic critique of Stalinist state communism made Animal Farm and 1984 instant classics. Steinbeck’s friendly focus on individual Russians in his text for the photos of Robert Capa humanized the USSR. The close chronology and contrasting content of Animal Farm, A Russian Journal, and 1984 suggest that Orwell singled out Steinbeck for reasons more troubling than literary pique or anti-American resentment.

Three books published between 1945 and 1949—George Orwell’s twin tales of totalitarian tyranny, Animal Farm and 1984, and John Steinbeck’s collaboration with Robert Capa, A Russian Journal—help explain why Orwell accused Steinbeck of being a “crypto-communist” in 1948. Orwell’s caustic critique of Stalinist state communism made Animal Farm and 1984 instant classics. Steinbeck’s friendly focus on individual Russians in his text for the photos of Robert Capa humanized the USSR. The close chronology and contrasting content of Animal Farm, A Russian Journal, and 1984 suggest that Orwell singled out Steinbeck for reasons more troubling than literary pique or anti-American resentment.

Animal Farm Anxiety

With characteristic irony Orwell subtitled his 1945 novel Animal Farm a “fairy story.” As a result Orwell’s manuscript was turned down by the Dial Press on the grounds that Americans weren’t buying children’s books. Editors in England were equally obstinate, but for political, not literary, reasons. Their motives were mixed, to put it mildly. Orwell’s London publisher Victor Gollancz—an unrepentant pro-Stalinist—deeply disliked Orwell’s depiction of politburo pigs exploiting sheep-like proletarians. T.S. Eliot—the Anglo-American editor at Faber & Faber who turned down Orwell’s first novel as pro-proletarian propaganda—rejected Animal Farm because it appeared to praise Trotsky.

In an act of semi-official censorship, a senior official in the British Ministry of Information (later exposed as a Soviet spy) warned London publishers not to accept Animal Farm because Stalin was England’s ally and publication could harm the war effort. As Russell Baker notes in his preface to the edition of Animal Farm published in America, the year Orwell wrote Animal Farm, “even conservatives were pro-Soviet” within England’s ruling class. Orwell neither forgave nor forgot, and 1943—the year he might have met Steinbeck but didn’t—marked the beginning of his obsession with writers, politicians, and snobs he found guilty of defending Stalin beyond the dictator’s past-due date.

Orwell neither forgave nor forgot, and 1943—the year he might have met Steinbeck but didn’t—marked the beginning of his obsession with writers, politicians, and snobs he found guilty of defending Stalin beyond the dictator’s past-due date.

Initially released in 1945 in a short print run by a small English press, Animal Farm was a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. Regular readers got the point missed by Eliot and Dial’s editors, and the allegory of Stalinist pigs and proletarian sheep made Orwell famous wherever it appeared. A group of exiles from Ukraine, the agricultural Russian heartland ravaged by a decade of famine and war, were among the book’s earliest fans. Understanding Orwell’s anti-Stalinist message from painful personal experience, they contacted the writer, who allowed them to publish Animal Farm without charge and wrote an introduction to the Ukrainian edition.

Animal Farm was Orwell’s first bestseller, and his advance amounted to $2,000 in today’s currency. Cannery Row, published at virtually the same time, was Steinbeck’s fifth or sixth bestseller, as Orwell was painfully aware. Described by one critic as a lighthearted confection with a poison center, Cannery Row is the antithesis of Animal Farm in purpose, point, and politics. Although both books are parodies meant to make readers laugh, Steinbeck wrote Cannery Row as an entertaining diversion for war-weary Americans. Beneath its sardonic surface, Animal Farm delivers a dire warning about conditions in Europe under fascism and communism: Contemporary life is like a farm. Totalitarians are pigs and you sheep are fools to follow them.

Steinbeck’s Russian Journey with Robert Capa

Orwell turned down invitations to visit the United States and never traveled to the Soviet Union, the subject of Animal Farm and 1984 and the cause of division among socialists following Stalin’s show trials and pact with Nazi Germany. When John Steinbeck visited Russian with his first wife in 1937, Orwell was fighting alongside his wife as an anti-Franco volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. In London six years later, Steinbeck became friends with Robert Capa, the photographer who accompanied him when he returned to Russia (without his second wife) in 1947. A Hungarian emigrant to France, Robert Capa—like Orwell—was on the scene during the savage civil war in Spain, photographing scenes that made him famous. Like Steinbeck, Robert Capa was self-invented, sponataneous, and unconstrained by social boundaries or orthodoxy—a better match for Steinbeck than Orwell had the writers met. The Eton-educated Orwell, born Eric Blair, was an intellectual, a partisan, and a bit of a prig.

The Eton-educated Orwell, born Eric Blair, was an intellectual, a partisan, and a bit of a prig.

A Russian Journal was published in 1948—text by John Steinbeck, images by Robert Capa—as Orwell was completing the first draft of 1984. To Orwell’s likely dismay, Steinbeck and Capa chose to focus on personal portraiture rather than group context in a Russian snapshot where politics are kept (mostly) out of the frame and individuals dominate the picture. Like the Joads, the Ukrainian farmers who extend hospitality to Steinbeck and Capa are fully-realized fellow beings, not proletarian symbols displayed against an Orwellian landscape. State-planned famine, Soviet show trials, and Stalinist treachery in Spain soured Orwell on the Soviet experiment earlier than other English socialists. Steinbeck’s characteristically American failure to denounce Stalin’s sins while praising Russian virtue must have seemed unforgivable, given what Orwell knew and when he knew it.

1984 and Beyond

The political allegory of Animal Farm morphed into futuristic nightmare in 1984, Orwell’s last and greatest book. Originally titled “The Last Man in Europe,” his story began to take shape in 1946 as the Iron Curtain fell across Europe and the Cold War ended Stalin’s temporary alliance with England and the United States. Using his royalties from Animal Farm, Orwell rented a remote house on an island off the northwest coast of Scotland, where he completed the final version of 1984 in 1948. Following a course strikingly parallel and opposite to Orwell career almost to the end, Steinbeck was living in self-imposed isolation in California, depressed by divorce from his second wife, the death of his best friend, and disparagement by New York’s literary elite. Whether Steinbeck read Animal Farm or 1984 during this period is unclear. But Orwell still practiced literary criticism, and it seems certain he was reading Steinbeck.

Steinbeck recovered and remarried in 1950, the year that Orwell—also remarried—died from tuberculosis. Diagnosed in 1948, Orwell’s disease was successfully treated with streptomycin, a still-scarce wonder drug invented in America and procured for Orwell by David Astor, the wealthy English son of American-born parents. Another friend named Richard Rees was at Orwell’s side when the drug and the author’s health failed in 1949, checking Orwell into a private sanitorium where they talked together about life, politics, and the list of communist sympathizers the writer was keeping in his notebook. According to Rees, his friend was “very weak, though mentally as active as ever.” In other words, Orwell knew what he was doing when he wrote Steinbeck’s name in the list of communist sympathizers the authorities should be watching.

Orwell knew what he was doing when he wrote Steinbeck’s name in the list of communist sympathizers the authorities should be watching.

According to Orwell biographer Michael Shelden, it was “a random list which mixes very famous personalities with obscure writers, and much of it is based on pure speculation.” Included with Steinbeck are two American artists of comparable celebrity: the expatriate singer-actor Paul Robeson and Orson Welles, creator of Citizen Cain and (like Steinbeck) outspoken critic of William Randolph Hearst and other demagogues of the Cold War American right. But most of Orwell’s suspects were English. Among them: Nancy Cunard, the socialist shipping heiress; C. Day Lewis, the future Poet Laureate and father-to-be of Daniel Day Lewis; Michael Redgrave, the knighted actor who founded a flourishing dramatic dynasty; and Britain’s perennial socialist playwright and journalist, George Bernard Shaw. Good company for a writer like Steinbeck, who enjoyed interesting associates, even when imaginary.

Orwell almost took his private list of suspected communists with him—but not quite—to his grave. The story of its survival begs an important question for Steinbeck lovers today: Was there anything more to Orwell’s accusation against Steinbeck than anti-Stalinist partisanship, anti-American parochialism, and professional pique? Seeking a higher authority, I turned to my late friend Christopher Hitchens, Orwell’s fellow socialist, disciple, and ardent defender.

Read more in Author Christopher Hitchens Defends Orwell’s Accusation.