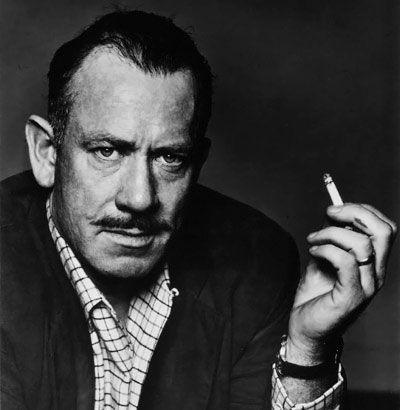

My discovery of John Steinbeck’s connection to the CIA could be described as payback for a youthful indiscretion—my own, not the author’s. While reading The Grapes of Wrath in high school, I skipped the “turtle” and other chapters that seemed to me superfluous to the plot line of the Joads’ journey west. The punishment for my teenage sin of omission came years later, when it first occurred to me that John Steinbeck was a CIA spy. The insane-sounding proposition grew from incongruities in Steinbeck’s life that—unlike Tom Joads’ turtle—I found I couldn’t ignore.

My discovery of John Steinbeck’s connection to the CIA could be described as payback for a youthful indiscretion—my own, not the author’s. While reading The Grapes of Wrath in high school, I skipped the “turtle” and other chapters that seemed to me superfluous to the plot line of the Joads’ journey west. The punishment for my teenage sin of omission came years later, when it first occurred to me that John Steinbeck was a CIA spy. The insane-sounding proposition grew from incongruities in Steinbeck’s life that—unlike Tom Joads’ turtle—I found I couldn’t ignore.

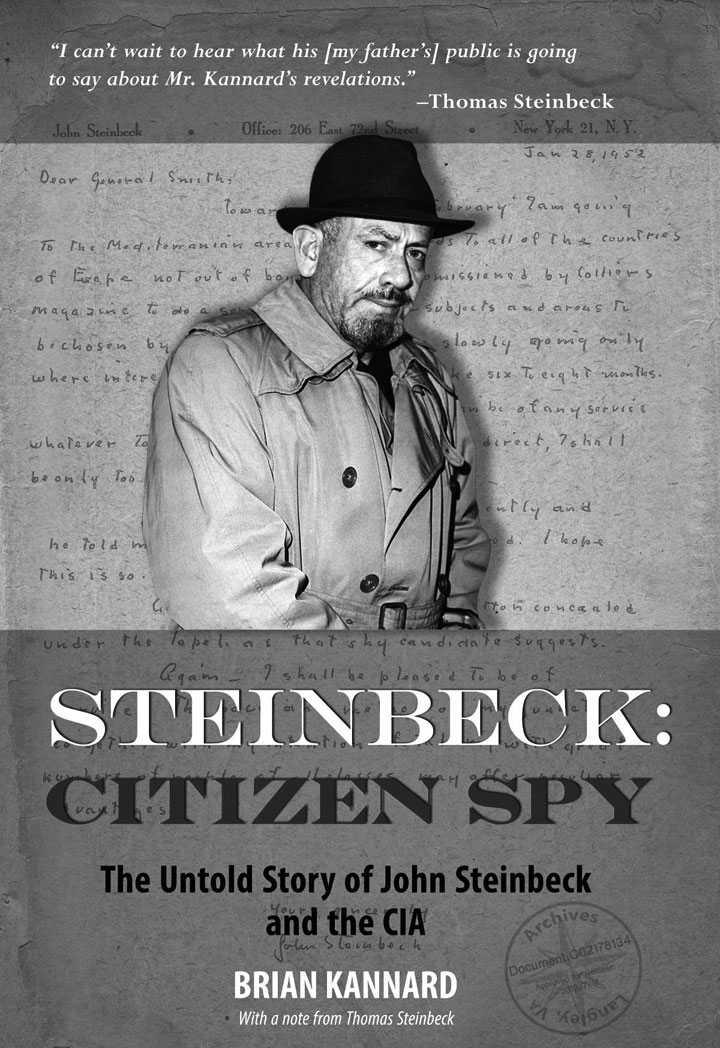

FOIA to the CIA: What Do You Have on John Steinbeck?

Why was Steinbeck never called before the House Select Committee on Un-American Activities, despite his alleged ties to Communist organizations? Why did the CIA admit to the Church Committee in 1975 that Steinbeck had been a subject of the illegal CIA mail-opening program known as HTLINGUAL? Did Steinbeck’s connections to known CIA front organizations, such as the Congress of Cultural Freedom and the Ford Foundation, amount to more than mere coincidence? Did the synchronicity continue when Steinbeck did freelance writing for the Louisville Courier-Journal and New York Herald Tribune? Both newspapers were linked to MOCKINGBIRD, another CIA operation, in Carl Bernstein’s 1977 Rolling Stone article “The CIA and the Media.” Why did the CIA redact portions of Steinbeck’s FBI files before they were released under the 1966 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the law that permits full or partial disclosure by government agencies of previously classified documents on request?

Why was Steinbeck never called before the House Select Committee on Un-American Activities, despite his alleged ties to Communist organizations?

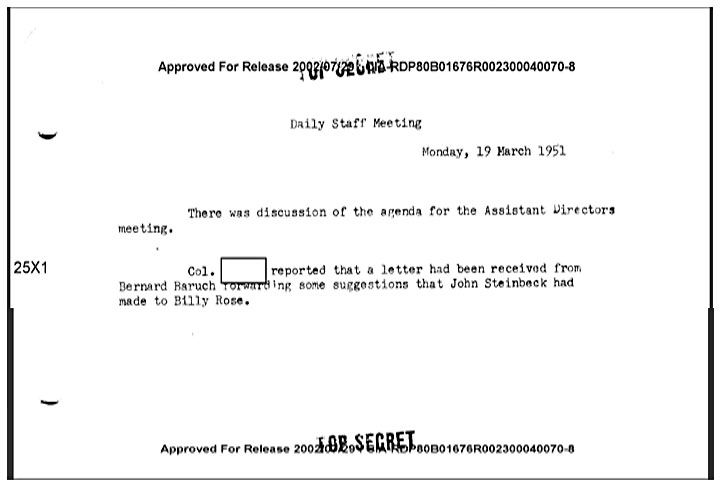

There was only one source—the CIA itself—that could definitively answer my questions and confirm or disprove my developing conclusions. I submitted my FOIA request to the CIA in January 2012. With characteristic bureaucratic speed, the CIA responded after eight months, in August 2012, sending me copies of two letters written in 1952. In the first, penned on personal stationery in his own handwriting, Steinbeck offers to work for the CIA. In the second, then-CIA Director Walter Bedell Smith accepts Steinbeck’s offer. The text of these letters and others can be found in my book, Steinbeck: Citizen Spy, at my website or in the FOIA Electronic Reading Room.

The CIA Director Accepts the Author’s Offer of Help

Jan 28, 1952

Dear General Smith:

Toward the end of February I am going to the Mediterranean area and afterwards to all of the countries of Europe not out of bounds. I am commissioned by Collier’s Magazine to do a series of articles—subjects and areas to be chosen by myself. I shall move slowly going only where interest draws. The trip will take six to eight months.

If during this period I can be of any service whatever to yourself or to the Agency you direct, I shall be only too glad.

I saw Herbert Bayard Swope recently and he told me that your health had improved. I hope this is so.

Also I wear the “Lou for 52” button concealed under the lapel as that shy candidate suggests.

Again—I shall be pleased to be of service. The pace and method of my junket together with my intention of talking with great numbers of people of all classes may offer peculiar advantages.

Yours sincerely,

John Steinbeck

‘If during this period I can be of any service whatever to yourself or to the Agency you direct, I shall be only too glad.’

ER 2-5603

6 February 1952

Mr. John Steinbeck

206 East 72nd Street

New York 21, New York

Dear Mr. Steinbeck:

I greatly appreciate the offer of assistance made in your note of January 28th.

You can, indeed, be of help to us by keeping your eyes and ears open on any political developments in the areas through which you travel, and, in addition, on any other matters which seem to you of significance, particularly those which might be overlooked in routine reports.

It would be helpful, too, if you could come down to Washington for a talk with us before you leave. We might then discuss any special matters on which you may feel that you can assist us.

Since I am certain that you will have some very interesting things to say, I trust, also, that you will be able to reserve some time for us on your return.

Sincerely,

Walter B. Smith

Director

O/DCI:REL:leb

Rewritten: LEBecker:mlk

Distribution:

Orig – Addressee

2 – DCI (Reading Official) [“w/Basic” has been handwritten beside this line and scratched out]

1 – DD/P [a check mark and w/Basic handwritten in]

1 – Admin [This has been scratched out] handwritten is “w/Basic”

‘You can, indeed, be of help to us by keeping your eyes and ears open on any political developments in the areas through which you travel.’

Did Steinbeck’s CIA Connection Start in Russia?

Reread A Russian Journal with the possibility that Steinbeck was working for the CIA prior to 1952 in mind. When Steinbeck traveled to the USSR with Robert Capa in 1947—the second of three trips the author made to the Communist state during his lifetime—Walter Bedell Smith happened to be the U.S. Ambassador to Russia. Steinbeck notes in his account of his and Capa’s Russian journey that they dined with Smith during their stay.

This experience helps explain the personal tone of familiarity expressed in Steinbeck’s 1952 letter to Smith offering to help the CIA. It also suggests the possibility that Steinbeck used his access while in the USSR to gather intelligence for the U.S. government from the Russian interior. While visiting a factory in Stalingrad, Steinbeck observes that the Russians are still melting down hulls from German tanks to make tractors fully two years after the end of World War II, lamenting his frustration at not being able to get current production figures for the facility. Such information would have been particularly important to the U.S. government in 1947, as the Cold War became hotter and American travel behind the Iron Curtain more difficult.

While visiting a factory in Stalingrad, Steinbeck observes that the Russians are still melting down hulls from German tanks to make tractors fully two years after the end of World War II, lamenting his frustration at not being able to get current production figures for the facility.

The 1952 exchange between the author of The Grapes of Wrath and the Director of the CIA provides a new set of parameters for understanding John Steinbeck’s life. In my book I carefully examine each of the letters resulting from my FOIA request to the CIA, the writer’s heavily CIA-redacted FBI files, Thomas Steinbeck’s thoughts on the matter, and likely avenues through which the elder Steinbeck could have served his government covertly both before and after 1952. Viewing the author’s life in terms of possible links to the CIA opens vistas for better comprehending certain works, such as The Short Reign of Pippin IV, that his literary agent, editor, and others discouraged him from writing. In recommending my book to a Steinbeck blogger, a noted Steinbeck scholar described the possible CIA-Steinbeck connection detailed in Steinbeck: Citizen Spy as “a potential game-changer.”

Time will tell.