Has Pope Francis read John Steinbeck? CBS News reporter Scott Pelley, a big fan of both men, thinks they have much in common in matters of justice, mercy, and conscience. (Barbara A. Heavilin, editor in chief of Steinbeck Review, agrees, relating the pope and the author’s shared hope for suffering humanity to an incident that occurred on a recent trip abroad.) During a 60 Minutes segment that aired on September 20, Scott Pelley previewed the pope’s historic visit to the United States, which included an address on Capitol Hill boycotted by three Catholic members of the Supreme Court’s conservative wing. Earlier, Pelley explained in a 60 Minutes Overtime interview why he handed Pope Francis an Italian edition of The Grapes of Wrath while on assignment in Rome in preparation for the segment. He said he was a descendant of displaced Dust Bowl victims who, like the “Okies” in The Grapes of Wrath, were refugees within their own country during the Great Depression. That connection, he explained, made John Steinbeck and Pope Francis more than news for him. It made them relevant.

Is Pope Francis a Fan of John Steinbeck? CBS News Reporter Scott Pelley Gives The Popular Pope a Copy of The Grapes of Wrath

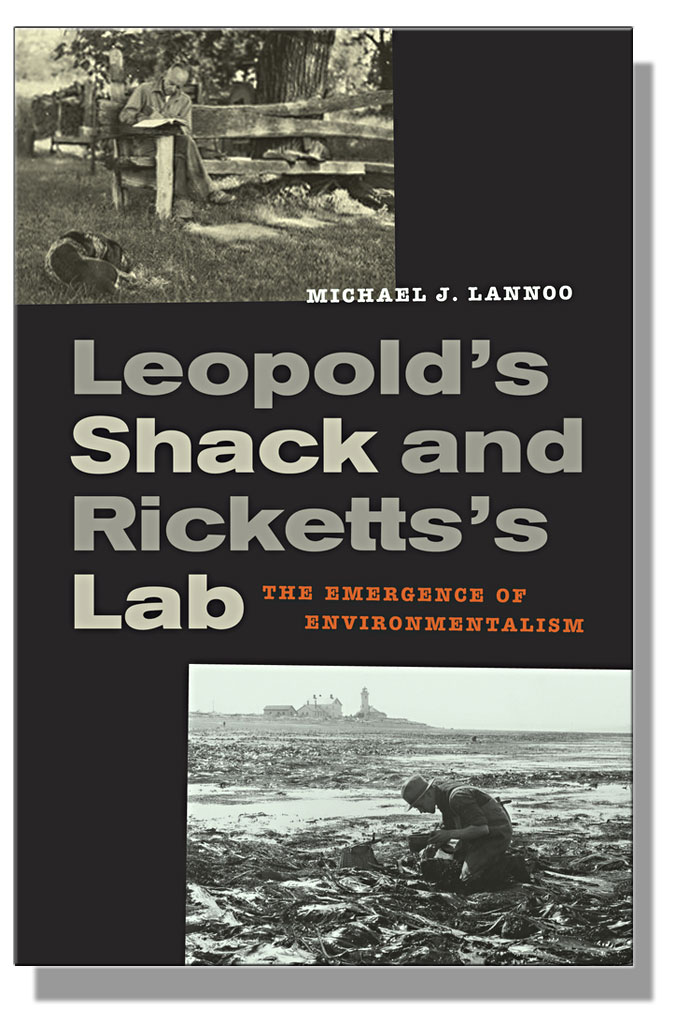

Ed Ricketts, Aldo Leopold, And the Birth of the Modern Environmental Movement

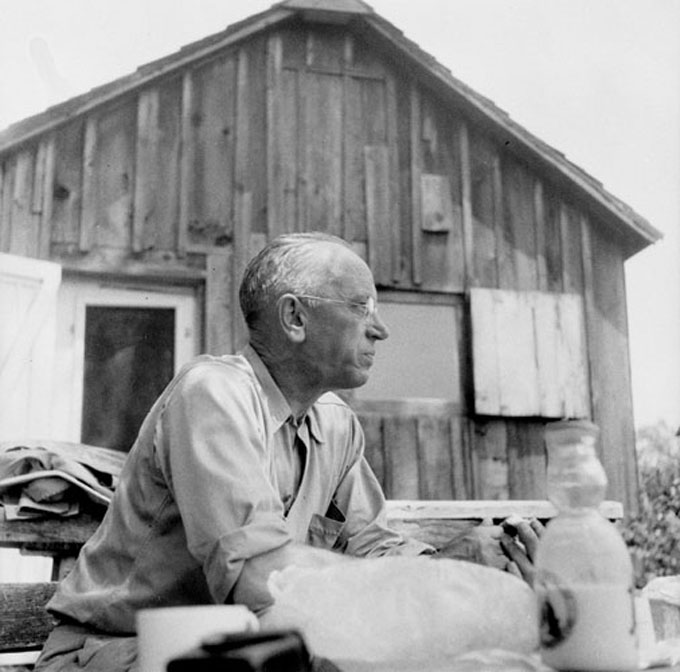

A bright, breezy book timed for the 75th anniversary of Ricketts and Steinbeck’s famous expedition to the Sea of Cortez traces today’s environmental movement and the modern field of conservation biology to two prophets born ahead of their time, 10 years and 200 miles apart, more than a century ago. As Michael J. Lannoo dramatically demonstrates in Leopold’s Shack and Ricketts’s Lab: The Emergence of Environmentalism, Aldo Leopold and Ed Ricketts approached wildlife biology, marine biology, and the earth’s ecology in a whole new way, the result of intimate observation, original thinking, and lively conversation at Ricketts’s lab on Cannery Row and Leopold’s shack on reclaimed farmland in Wisconsin—apt metaphors for the sociable minds of two unconventional scientists whose parallel paths never crossed.

The story of Ricketts, marine biology, and the 1940 collecting expedition to the Sea of Cortez is familiar territory for Steinbeck fans and “Ed Heads,” the ardent admirers who consider Doc’s lab a shrine, like Lourdes. A less familiar narrative, equally fateful, was unfolding in the woods of Wisconsin during the same period, the 1930s and 40s, in the shack and mind of Aldo Leopold, the father of professional wildlife biology and author of Sand County Almanac (1949). Like Sea of Cortez, Leopold’s classic took time to gain steam; like Ricketts, Leopold died too soon to see his ideas change the course of science, land management, and the way we think.

Leopold died of a heart attack on the Wisconsin land he loved in 1948, months before the book that made him an environmental-movement hero was published. Two weeks later Ricketts was also dead, the result of injuries sustained when his car struck a train near his Cannery Row lab. Leopold, 10 years Ricketts’s senior, never met the transplanted Chicago native who made Cannery Row famous, in fiction and in fact. But Ricketts’s mystical thinking about marine biology eventually converged with Leopold’s ethic of wildlife biology to create the field of conservation biology and the holistic vision of today’s environmental movement, a benign way of living with nature minus the impulse to over-farm, over-fish, over-build, and over-populate. Like Steinbeck, Leopold was angered by urban sprawl and consumer waste. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts, he thought science was a saner faith than religion.

Ricketts’s mystical thinking about marine biology eventually converged with Leopold’s ethic of wildlife biology to create the field of conservation biology and the holistic vision of today’s environmental movement.

Leopold and Ricketts, opposites types in personality and behavior, come to life like the parallel protagonists of a Steinbeck novel in Lannoo’s elegant little book. Like all prophets, both men had their problems with power. Though Leopold’s 1933 work on game management became the standard textbook of its time, Sand County Almanac was passed over by publishers who doubted the commercial value of any collection of essays about nature not named Walden. Ricketts’s Between Pacific Tides (1939) eventually become a standard text for teaching marine biology, but not before it was rejected, accepted with edits, then endlessly delayed by Stanford University, its publisher. As for Sea of Cortez, does anyone think Viking Press would have touched that book without John Steinbeck’s name on the byline over “E.F. Ricketts”? True, Steinbeck mourned Ricketts’s death, but he later agreed to republish Sea of Cortez, with an essay “About Ed Ricketts” but without Ricketts’s name as co-author.

Leopold and Ricketts, opposites types in personality and behavior, come to life like the parallel protagonists of a Steinbeck novel in Lannoo’s elegant little book.

Fortunately, Michael Lannoo—a practicing scientist and popular writer about conservation biology—ignores this shameful incident, and other fetishes of what one wag calls the modern Steinbeck-studies industrial complex. Instead, he concentrates on the lives and science of his told-in-tandem subjects without the literary baggage that weighs down books about the anxiety of influence and the pleasures of symmetry by professors of English. He wisely lets Leopold and Ricketts stand on their own, unfolding their parallel stories in alternating chapters with Steinbeckian skill. Robert DeMott, the scholar and fly-fisherman who turned me on to this little gem, accurately describes Lannoo’s book as “blessedly free of cant, jargon, or technical obfuscation.” Read it and rejoice, but hear its message. Like Ricketts (who quit college) and Leopold (who went to forestry school), you don’t need a PhD to enjoy the exciting story or get the scary point. The disappearance of frogs and other species, Lannoo’s primary interest, is our generation’s Dust Bowl—“the defining event,” as Lannoo reminds us, “that made ecology suddenly relevant.”

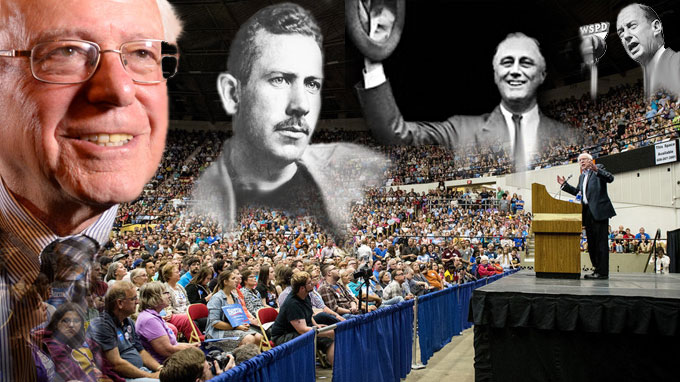

Why John Steinbeck Would Support Bernie Sanders Now

If John Steinbeck were alive today he would support Bernie Sanders for president.

Why? Because Bernie Sanders is the kind of outspoken progressive the author of The Grapes of Wrath enthusiastically embraced during his controversial career as a prize-winning writer of popular fiction. A passionate believer in fair play, Steinbeck endorsed presidential candidates committed to populist causes, actively campaigning for Franklin Roosevelt, who was elected four times, and Adlai Stevenson, who ran twice but lost both races. More than either man, Bernie Sanders talks straight in plain language about equality and integrity, Steinbeck’s core values—a New England character trait that Steinbeck both admired and inherited. The Sanders movement is about issues, not personality; Steinbeck wanted to be remembered for his books, not his life. But his life was public and political, and a little biography is needed to show why he’d be for Bernie Sanders today.

Why John Steinbeck and Bernie Sanders Would Get Along

Steinbeck was born in Salinas, California, in 1902, and grew up in the small town during the era of Theodore Roosevelt, the Republican President who busted the big business trusts and moved to curtail private exploitation of public lands by creating parks such as Yosemite. John’s mother was an ex-schoolteacher and tireless civic volunteer. His father was a failed small-businessman who became the elected Treasurer of Monterey County. His mother’s parents emigrated from Ireland, while his father’s people were New Englanders—half-English and half-German. Both parents were Party-of-Lincoln Republicans who believed in social improvement, access to education, and reforming government to make it work better. Steinbeck was proud of these roots, later writing that everybody in Salinas was a Republican back then, and that if he had stayed in Salinas he would have become one, too.

Steinbeck was proud of his roots, later writing that everybody in Salinas was a Republican back then, and that if he had stayed in Salinas he would have become one, too.

Like Bernie Sanders, John Steinbeck grew to distrust the corrupting influence of corporations and how working people were manipulated to vote against their economic self-interest—urban vs. rural, native- vs. foreign-born, small farmers and white laborers vs. Mexicans, Chinese, Filipinos, and refugees from the Dust Bowl. He hated the social snobbery he encountered as a student at Stanford University in the 1920s, working as a field hand and night watchman in summers and off-semesters to help pay his way but quitting before getting a degree. In 1925 he left for New York to find his own way. There, like Bernie Sanders, he failed at more than one job before returning to California to make ends meet as a caretaker-handyman on a rich man’s estate. The Great Depression that resulted from Wall Street’s collapse in 1929 gave Steinbeck the subject he needed to become a politically engaged writer: the brutal suppression of non-union workers by California’s big business interests. The state’s powerful industrial-agriculture complex became the target of his 1939 masterpiece, The Grapes of Wrath.

The Great Depression that resulted from Wall Street’s collapse in 1929 gave Steinbeck the subject he needed to become a politically engaged writer: the brutal suppression of non-union workers by California’s big business interests.

Also like Bernie Sanders today—and most Americans at the time—Steinbeck believed in gun-rights, but was too tenderhearted to hunt. Instead, he kept a gun for self-protection. Hired thugs threatened to break his legs or worse for what he was writing about workers’ rights, even before The Grapes of Wrath, and the sheriff warned him of a plot to set him up for a rape charge. Threats failed to change his mind, and the celebrity he achieved through his writing changed his behavior but not his character. Like Bernie Sanders, he remained pro-labor all his life and more at ease with working people than with billionaires. He refused to own a Ford because Henry Ford was an anti-union anti-Semite whose cars Steinbeck thought inferior. Steinbeck described another billionaire as so driven by avarice that late-life regret forced him to try buying his way into heaven through philanthropy.

Like Bernie Sanders, he remained pro-labor all his life and more at ease with working people than with billionaires. He refused to own a Ford because Henry Ford was an anti-union anti-Semite whose cars Steinbeck thought inferior.

The greatest influence on Steinbeck’s thinking about politics was probably his first wife, Carol Henning, a progressive activist who suggested the title of The Grapes of Wrath. Together they supported the New Deal programs of President Franklin Roosevelt, whose First Lady became Steinbeck’s friend and ally. Like Bernie Sanders, however, Steinbeck had a wise way of not rejecting those who disagreed with him about party affiliation. He remained loyal to his Republican sisters, though he deeply disliked their fellow Californian Richard Nixon, and he despised William Randolph Hearst, the father of yellow journalism—the Fox News of American politics at the time. Steinbeck died in New York the month after Nixon was elected president in 1968. If Steinbeck and Bernie Sanders had met in the ’60s, unlikely but conceivable, they would have agreed about the movement for desegregation and voting rights and disagreed about the war in Vietnam, an issue that eventually got Steinbeck in trouble with his friends.

John Steinbeck, Franklin Roosevelt, and Adlai Stevenson

When Steinbeck’s enemies accused him of being Jewish because of his surname and his sympathies, he replied that he would be pleased if it were so. In reality his religious roots were Protestant, and he grew up in the Episcopal Church—the church of Franklin Roosevelt, a New York aristocrat of Dutch descent whom detractors also accused of being a Jew. Just as Steinbeck’s parents had supported the progressive policies of Teddy Roosevelt, FDR’s Republican cousin, Steinbeck advocated Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal as a way out of the pain and suffering caused by Wall Street in the Great Depression. When world war broke out the year The Grapes of Wrath was published, Steinbeck found himself blackballed by military bureaucrats in Washington and abused by his local draft board. Despite his support for FDR and the fight against Fascism, he questioned the government’s internment of Japanese-Americans and criticized pro-war propaganda created by New York ad men and Hollywood studio warriors. After showing courage under fire as an embedded newspaper correspondent on the Italian front, he was refused the award for valor that many thought he deserved. When he returned to the United States he said the worst thing about war was its dishonesty.

Despite his support for FDR and the fight against Fascism, he questioned the government’s internment of Japanese-Americans and criticized pro-war propaganda created by New York ad men and Hollywood studio warriors.

Doubts about the Cold War, plus Eleanor Roosevelt’s endorsement, motivated John Steinbeck to support Adlai Stevenson over Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956. Stevenson’s cool intelligence and firm grip on fact-based reality appealed to Steinbeck’s intellect, which he developed by dialogue and research. The same traits made Stevenson a target of Cold Warriors from both parties connected to what Eisenhower later called out as the military-industrial complex in his last State of the Union address. Stevenson was an independent-minded politician with a consistent message, an activist following, and an aversion to the kind of character assassination used against him when he ran for president. Like Franklin Roosevelt and Bernie Sanders, he was John Steinbeck’s idea of an authentic progressive.

Adlai Stevenson was an independent-minded politician with a consistent message, an activist following, and an aversion to the kind of character assassination used against him when he ran for president. Like Franklin Roosevelt and Bernie Sanders, he was John Steinbeck’s idea of an authentic progressive.

Along with Eleanor Roosevelt, Steinbeck encouraged Stevenson to run again in 1960 before shifting his support to John Kennedy. After the election Stevenson and Steinbeck grew close, closer than Steinbeck ever was to Franklin Roosevelt. Like Bernie Sanders, Stevenson had a scientific, secular worldview that attracted Steinbeck but invited opponents to characterize Stevenson as an egghead who was unqualified to be president because he read books and liked culture. Steinbeck, who wrote long books, shared Stevenson’s enthusiasm for music and reading. Cool Bach was playing in the background as Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath. So was the edgy music of Igor Stravinsky, a Russian refugee with a wild, insistent sound more like Bernie Sanders than Bach or Adlai Stevenson.

But Couldn’t John Steinbeck Be for Hillary Clinton?

Answer: If Bernie Sanders weren’t running, yes, but with reservations. Here’s why.

John Steinbeck’s third wife was a Texas friend of Lady Bird Johnson, and the Steinbecks were White House guests when LBJ needed help with the intellectuals he thought Steinbeck, like Stevenson, represented. It’s easy enough to imagine Elaine Steinbeck, the first non-male stage manager in Broadway history, favoring a female candidate for president today. But the influence she exerted turned out badly for her husband in the 1960s. Steinbeck’s sense of loyalty to the Johnsons led him to get the Vietnam War very wrong, despite the lesson he learned in World War II. He kept his mouth shut in public after touring Southeast Asia at Johnson’s urging. In private he confessed that the government had no business interfering in the civil war of a country that hadn’t attacked America.

Today John Steinbeck would be for Bernie Sanders, the no-nonsense New Englander with a consistent record on everything that mattered most to Steinbeck: social justice, individual integrity, and saving the people and the planet Steinbeck celebrated in The Grapes of Wrath.

If he’d lived, Steinbeck would have opposed the Bush-Cheney wars for the same reason—plus the deceit and dishonesty used to justify the invasion of Iraq. At the time, Bernie Sanders joined Barack Obama in opposing the Iraq war from the floor of the U.S. Senate. Like a Cold War Democrat in the days of Lyndon Johnson, however, Senator Clinton went along with the crowd and voted yes. Steinbeck paid dearly, in reputation and in conscience, for following the White House line on Vietnam, despite his distrust of Wall Street and warmongering and his understanding of their connection. Given that experience, he’d distrust Clinton—for her Wall Street friends as much as for her flip-flopping on Iraq. In 2008 Steinbeck would have supported Obama—an egghead from Illinois, like Adlai Stevenson—and rejoiced in the result. Today he’d be for Bernie Sanders, the no-nonsense New Englander with a consistent record on everything that mattered most to Steinbeck: social justice, individual integrity, and saving the people and the planet Steinbeck celebrated in The Grapes of Wrath.

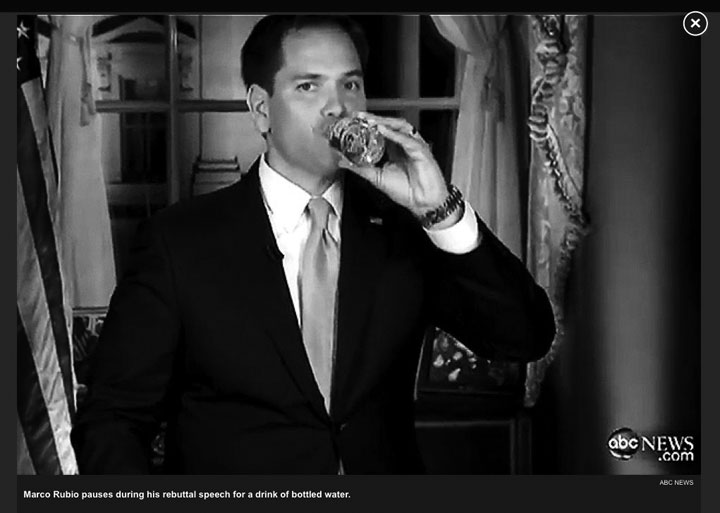

John Steinbeck Explains Marco Rubio on Global Warming in Sea of Cortez

This week the issue of global warming caused embarrassing problems for Marco Rubio as the Republican Senator from Miami rolled out his unofficial entry into the 2016 presidential race. Sorry, but I couldn’t help noticing. Although I am not a Republican and no longer live in Florida, I once owned a home on the Intracoastal Waterway near Palm Beach. During hurricanes, our little beach disappeared along with half of our yard. A two-foot sea rise will leave storm water at the new owner’s front door. Another two feet will make the house, along with thousands of other coastal homes, uninhabitable. So I’ve been scratching my head over the confused case Marco Rubio tried to articulate for doing nothing to mitigate global warming—an odd position for any elected official from South Florida to take. Oops! There goes Miami Beach!

I’ve been scratching my head over the confused case Marco Rubio tried to articulate for doing nothing to mitigate global warming. Oops! There goes Miami Beach!

As usual, John Steinbeck helped me think. Because his science book Sea of Cortez is also political and philosophical, I turned to the writer’s “Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research” in the Gulf of California to help me understand politicians like Marco Rubio who (1) deride global warming data, (2) deny that fossil-fuel use is a factor, or (3) insist that it’s too late to turn back, so what the hell! During the course of speeches and interviews in New Hampshire and elsewhere, Marco Rubio denied global warming so often and so recklessly that he became the butt of a Wednesday night Stephen Colbert Show “F*ck It!” segment. What part of Rubio’s brain shut down when he opened his campaign for president? Three observations made by John Steinbeck on the biology of belief and behavior in Chapter 14 of Sea of Cortez provided clarity, but little comfort, about Marco Rubio’s recent statements regarding global warming. Hold the applause. They are nothing to laugh about.

1. Forget simplistic causation. Find provable relationships and prepare for complexity.

Sea of Cortez starts with first principles. From microbes to mankind, variation in nature is a universal principle; causative relationships are complex and outcomes aren’t always predictable. But worldwide climate disruption is a particularly violent variation with measurable relationships and very clear consequences. Denying the significance of man-made carbon emissions in accelerating global warming by implying, as Marco Rubio and others do, that . . . well, shit happens . . . is like letting a drunk drive on the theory that other things can go wrong too, so what’s the big deal? Ignition failure, bad brakes, lousy weather, all contribute to accidents on the road. But driving while drunk, like loading the atmosphere with pollutants, foolishly increases the severity and consequences of co-contributing factors.

Driving while drunk, like loading the atmosphere with pollutants, foolishly increases the severity and consequences of co-contributing factors.

“Sometimes,” John Steinbeck would have agreed, “shit just happens.” But try taking that excuse to court and see what happens there—if you survive the wreck you caused. Steinbeck was a Darwinian who tried not to judge, but deadly driving while drunk has been described by those who are less forgiving as a form of natural self-selection for stupid individuals. Unlike solitary drinking, however, global warming denial is a social disease. Following the dimwitted herd of reality-deniers, like lemmings, over the looming climate cliff? That takes systematic self-delusion and self-styled leaders like Marco Rubio. How do they operate? John Steinbeck had a theory.

2. Reality-denial is a form of adolescent wish-fulfillment. It’s most dangerous in a mob motivated by a self-appointed leader.

Sea of Cortez—co-authored with Steinbeck’s friend and collaborator, the marine biologist Ed Ricketts—develops many of the ideas Steinbeck expressed in the fiction he wrote before 1940. His 1936 novel In Dubious Battle, for example, dramatized the murderous behavior of opposing mobs, behavior worse than anything within the capacity of their individual constituents. Steinbeck’s characterization of politically-driven leaders like Mac, the novel’s Communist labor-organizer, is particularly disturbing, even today. Sea of Cortez develops both of these core ideas—the behavior of mob members and the psychology of mob leaders—using biological terms that help explain Marco Rubio and his position on global warming.

Sea of Cortez develops both of these core ideas—the behavior of mob members and the psychology of mob leaders—using biological terms that help explain Marco Rubio and his position on global warming.

Like Steinbeck’s metaphorical ameba in Sea of Cortez, Mac the Communist and Marco Rubio the Republican are political pseudo-pods who detect a mass-wish within their followers and press toward its fulfillment: “We are directly leading this great procession, our leadership ‘causes’ all the rest of the population to move this way, the mass follows the path we blaze.” But one difference between Mac and Marco Rubio, worth noting, was apparent in this week’s events. Steinbeck’s labor agitator was a tough guy with street smarts who stayed on-message; Marco Rubio manages to look as unfixed and immature as he sounds. In right-wing global warming politics, Rick Perry—no George Bush, and take that as a compliment—seems statesmanlike by comparison. Oops! I meant Department of Education!

3. Extinction is possible. Double extinction.

John Steinbeck read encyclopedically, and in Sea of Cortez he explains what he calls “the criterion of validity in the handling of data” by citing an example from an article on ecology in the 14th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica. It concerns the extermination of a certain species of hawk that preyed on the willow grouse, a game bird in Norway. Failing to note the presence of the parasitical disease coccidiosis in the country’s grouse population, the Norwegians systematically eradicated the predator that kept the infection under control by killing off weaker birds affected by the disease. The result was double extinction—hawk and grouse—caused by uninformed human behavior.

The Norwegians systematically eradicated the predator that kept the infection under control by killing off weaker birds affected by the disease. The result was double extinction—hawk and grouse—caused by unintelligent human behavior.

Like Steinbeck, I loved college biology, and the biology department at Wake Forest was very good. My freshman professor, a John Steinbeck-Ed Ricketts type named Ralph Amen, introduced us to an idea that makes Marco Rubio’s anti-global warming demagoguery more than a little scary 50 years later. “Imagine,” Dr. Amen suggested, “that the earth is an organism, Gaia, with a cancer—the human species, overpopulating and over-polluting its host. What is the likely outcome of this infection for Gaia and for mankind?” A question in the spirit of Sea of Cortez, which on reflection I’m certain he had read.

‘Imagine,’ Dr. Amen suggested, ‘that the earth is an organism, Gaia, with a cancer—the human species, overpopulating and over-polluting its host. What is the likely outcome of this infection for Gaia and for mankind?’

John Steinbeck, a one-world ecologist even further ahead of his time than my old teacher, would have answered, “things could go either way.” The cancer might kill the host or the host eradicate the cancer. But global warming presents a third possibility—double extinction. Now imagine that Marco Rubio is a soft, squishy symptom of global warming denial, a terminal disease. Then reread John Steinbeck’s Sea of Cortez as I just did. Reality-based thinking is our first step toward a cure, although under a president like Marco Rubio it could also be our last. Oops! There we go—along with the planet! How in the world did we let that happen?

Cannery Row’s Human Parade: Helpful Hints for Better Training Design

As an instructional designer in business and industry I had the responsibility for preparing employees to face critical and risky tasks—ones that demanded courage and flawless creativity. It is a fact that most risky tasks are handled alone and not by a team or committee. To meet the challenges, I had to replace the usual classroom experiences with new training methods that considered the whole work environment. My methods were built on the ideas of the psychologist Carl Jung that were applied so well by John Steinbeck in his fiction and non-fiction, including Cannery Row, Sweet Thursday, The Log From the Sea of Cortez, The Moon Is Down, and East Of Eden. What follows continues the line of inquiry in my most recent post.

As an instructional designer in business and industry I had the responsibility for preparing employees to face critical and risky tasks—ones that demanded courage and flawless creativity. It is a fact that most risky tasks are handled alone and not by a team or committee. To meet the challenges, I had to replace the usual classroom experiences with new training methods that considered the whole work environment. My methods were built on the ideas of the psychologist Carl Jung that were applied so well by John Steinbeck in his fiction and non-fiction, including Cannery Row, Sweet Thursday, The Log From the Sea of Cortez, The Moon Is Down, and East Of Eden. What follows continues the line of inquiry in my most recent post.

Like Carl Jung, John Steinbeck understood the principle well, as shown in a letter to John O’Hara, his friend and fellow writer:

“I think I believe one thing powerfully-that the only creative thing our species has is the individual lonely mind. Two people can create a child but I know of no other thing created by a group. The group ungoverned by individual thinking is a horrible destructive principle. . . . “

As a result of my study, it became very clear to me that while individuals were facing creatively demanding tasks alone, the physical and social environment in which the creative effort must be undertaken influences job-holder perception, judgment, problem-solving, and decision-making—and inevitably, success or failure.

Carl Jung, Cannery Row, and the Human-Persona Divide

In my assignments as a training program developer, I became curious about the influences of the work environment on the individual. My goal was to create a richer and more realistic learning experience. I had years of independent study of Carl Jung and was aware of his influence on John Steinbeck’s fiction and non-fiction. Both inspired my efforts and spurred my curiosity.

As a result of reading Jung and Steinbeck, I began to understand why particular types of individuals seem to gravitate to certain jobs. For example, the personality difference between the engineer- and customer service and marketing-types is typically dramatic. What did John Steinbeck have to say about this particular human-persona divide? It seemed obvious to me that the Cannery Row character Doc would not have made a successful sporting house manager like Dora, and that Mack would have been a poor replacement for Doc in the role of Caretaker for the Row. Strong characters all, but hardly interchangeable.

Delving deeply into The Log From the Sea Of Cortez—John Steinbeck’s collaboration with Ed Ricketts, the model for his Cannery Row character Doc—I was struck by the idea that a person’s social and physical environment is no more random than that of the tide pool creatures described by the authors:

“We wanted to see everything our eyes would accommodate, to think what we could, and, out of our seeing and thinking, to build some kind of structure in modeled imitation of the observed reality. We knew that what we would see and record and construct would be warped, as all knowledge patterns are warped, first, by the collective pressure and stream of our time and race, second by the thrust of our individual personalities. But knowing this, we might not fall into too many holes-we might maintain some balance between our warp and the separate thing, the external reality.”

A Cannery Row-Sweet Thursday Human-Type Continuum

A training program, physical environment has purpose, patterns, lessons, and consequences like those imposed by the surrounding tide pool environment on a biological specimen. The life in a peaceful, safe, and unchallenging tide pool may actually impede species evolution and survival. The microbes that infect us evolve and strengthen in response to antibiotics designed to kill them. Grapes from a difficult growing season often produce superior wine. Trainees who survive a practical-and stressful- learning environment may likewise perform better than others on the job.

Consider the social environment and social impact upon the denizens of Cannery Row in Sweet Thursday, John Steinbeck’s sequel to the earlier novel:

“To a casual observer Cannery Row might have seemed a series of self-contained and selfish units, each functioning alone with no reference to the others. There was little visible connection between La Ida’s, the Bear Flag, the grocery (still known as Lee Chong’s Heavenly Flower Grocery), the Palace Flop house, and Western Biological Laboratories. The fact is that each was bound by gossamer threads of steel to all the others—hurt one, and you aroused vengeance in all. Let sadness come to one, and all wept.”

Or, by contrast, the following passage from Cannery Row:

“The previous watchman was named William and he was a dark and lonesome-looking man. In the daytime when his duties were few he would grow tired of female company. Through the windows he could see Mack and the boys sitting on the pipes in the vacant lot, dangling their feet in the mallow weeds and taking the sun while they discoursed slowly and philosophically of matters of interest but of no importance. Now and then as he watched them he saw them take out a pint of Old Tennis Shoes and wiping the neck of the bottle on a sleeve, raise the pint one after another. And William began to wish he could join that good group. He walked out one day and sat on the pipe. Conversation stopped and an uneasy and hostile silence fell on the group. After a while William went disconsolately back to the Bear Flag and through the window he saw the conversation spring up again and it saddened him. He had a dark and ugly face and a mouth twisted with brooding. The next day he went again and this time he took a pint of whiskey. Mack and the boys drank the whiskey, after all they weren’t crazy, but all the talking they did was “Good luck,” and “Lookin’ at you.” After a while William went back to the Bear Flag and he watched them through the window and he heard Mack raise his voice saying, “But God damn it, I hate a pimp!” Now this was obviously untrue although William didn’t know that. Mack and the boys just didn’t like William.”

Individual Levels in John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down

Just as examining a biological specimen in its surrounding tide pool yields greater information than isolated examination in a laboratory, we can learn more about individuals by studying them within their physical and social environment than in solitude. Conceptual tools such as Carl Jung’s functional and attitudinal types and Jim Kent’s Gathering Place Roles (discussed previously in this series) further expand our horizon. Deeper drilling reveals why particular Jungian functional types and attitudes will gravitate naturally to specific Gathering Place roles.

As noted in the first of these blog posts, human beings range in maturity from simple, unconscious types to highly evolved individuals who are conscious about and in control of their lives. Now I would like add my observations about groups made up of members who have not achieved higher maturity:

1. If there is any social structure at all, the social body will be vertically directed by leaders who have realized how easy it is to influence the citizens to do their will, usually for selfish and evil reasons. “Tell the population anything and repeat it many times and they will believe it” (Adolf Hitler paraphrased).

2. Less-evolved citizens who have not awakened to the possibility of their unique self and self-direction and will easily surrender their freedom to father or mother figures, real or imagined, and remain unaware of the resulting personal cost.

3. Such followers do not actively direct their lives beyond providing for the basics of assuring food, shelter, and procreation.

4. They project upon external gods, including father and mother figures, and are closed to suggestions from outside the social group: all thinking has been entrusted to the mother or father figure.

5. Total leader-control is possible simply by publishing of a list of “ought-and-must” dictates.

6. The leadership will be threatened by anyone who refuses to surrender his or her freedoms. Given the usual absolute power of the leaders, it is simple to incite mass or MOB confrontation against those who threaten challenge or change, sometimes cruelly and violently.

Where individuals of higher maturity comprise the group the following can be observed:

1. The leadership unselfishly serves its citizens.

2. “Ought-and-must” dictates are almost useless to control the citizenry comprised of higher-evolved individuals.

3. The life of the citizens has more potential for happiness and completeness.

4. Within this positive and loving environment, interpersonal struggles will persist because everyone will not agree on every issue. There is a noticeable difference between interpersonal struggles within a loving social environment and the ones where there is virtual sibling-rivalry for the father or mother figure’s attention. Adolf Hitler actually encouraged such confrontation among his leadership.

5. Highly evolved individuals have learned that there is more in play in themselves than mere ego and have begun to explore and integrate newly discovered psychological territory. This is perhaps the most important step to becoming a complete individual.

6. The collective power for good often exceeds what would be anticipated from apparent resources. Unexpected strength and adaptability will come out of the positive and powerful phalanx of more mature individuals.

In The Moon Is Down, John Steinbeck portrayed a community of evolved (per my recent post, Level 3 and Level 4) men and women, dramatizing the power of such a phalanx in response to occupation by father-figure representatives of a distant and despotic leader. The Nazi spokesman advises the mayor to “think for” his people:

“’It is your duty to protect them from harm. They will be in danger if they are rebellious. We must get the coal, you see. Our leaders do not tell us how; they order us to get it. But you have your people to protect. You must make them do the work and thus keep them safe.’ Mayor Orden asked, ‘But suppose they don’t want to be safe?’ ‘Then you must think for them.’ Orden said, a little proudly, ‘My people don’t like to have others think for them. Maybe they are different from your people. I am confused, but that I am sure of.’”

With the various levels of individual evolution in mind, consider the history of freedom-loving Scotland with the citizens being served by the Stewart monarchy. Go back further, to the Britons and King Arthur—John Steinbeck’s ideal of dedication to duty and chivalry. Fast forward to the Ottoman Empire, where the rights of all religions were guaranteed by proclamation. Consider the social environment surrounding the Library at Alexandria—destroyed by Christians—where citizens of all cultures, ideals, and creeds mingled and freely shared their knowledge and wisdom.

Needs Analysis and Jung and Steinbeck’s Human Factor

In my instructional design career I was responsible for providing training in tasks as simple as completing personnel time records and as complex as monitoring and controlling complicated electric generating-station systems. As noted, my programs were also used to prepare teams of consultants to influence and support communities that were facing challenges. In many cases, my job required the analysis of complex systems and processes, human-to-system interface, and interpersonal and social issues, using Needs Analysis to define the gap between existing competency levels and those needed to do the job with greater expertise.

Needs Analysis provide the necessary information to design training models, proposals, and justification, cost-benefit, and standards. Technical and complex-process analysts normally have abundant technical and process data available for their task. But complex critical-skill competencies also include personal and interpersonal components such as individual jobholder style, strengths, weaknesses, creativity, perception, judgment, and decision-making, problem-solving, risk-management skills.

But the analyst’s intellect is as critical to the success of the process as the technical tools developed in preparation for the act of training. Yet the humanities side of the training is all too often ignored in the process. The briefest examination of technical-owner manuals shows how poorly qualified most computer programmers and engineers are to write useful guides for the non-technical user. Worse still, to an experienced instructional designer, the engineer’s boast that he has emulated the cognitive processes of the human mind in designing artificial intelligence and expert systems for human use is laughable at best.

When I awoke to the need for a more holistic critical skills-training perspective, little was available to guide me in the human elements of the equation beyond publications by psychological behaviorists such as Thomas F. Gilbert and Robert Mager. But their view was limited to statistically defined and empirically observable behavior and ignored the influence of individual will and social environment. In my opinion they were uninterested in the factors that form our uniqueness and individual creativity. To develop a more complete program I knew that a broader perspective was required, providing a bigger window from which to analyze work processes and standards in greater depth and detail.

The program developers I managed were almost exclusively specialists and technical experts inexperienced in or ignorant of the humanities. To do a more thorough job, their subject-matter expertise needed bolstering with knowledge of human factors, attributes, and cognitive functions. Failure to consider these essential elements within the context of a given task accounts for many problems, notably in military training, pilot training simulation, nuclear power plant operation, ship navigation, and other life-and-death tasks. The 1979 near- disaster at Nuclear Generating Station Number Two on Three Mile Island is a dramatic example of this danger.

Was John Steinbeck Right About Religion and Freedom?

But was John Steinbeck always right about the individual? In the forward to a later edition of A Russian Journal he was quoted: “The great change in the last 2,000 years was the Christian idea that the individual soul was very precious.” I disagree, and I think Steinbeck knew better. Historically Christianity has cruelly suppressed individual behaviors and beliefs that appeared to challenge official doctrine and church control. In this regard, it is a religion with much company in the parade of human history.

The suppression of individual freedom remains an impediment to the general improvement of the human condition. As Steinbeck showed in The Moon Is Down, the simple act of raising individual consciousness from Level 1 to Level 2 improves the quality of the collective. In East of Eden, written 10 years later, the original sin isn’t eating the apple of the tree, suggesting that Eden was incomplete without self-knowledge—the real fruit of the forbidden tree. Eve is denigrated by the religious for taking that first bite of freedom. To the contrary, I am convinced that Adam benefitted from the reported act of her original disobedience. I suspect that John Steinbeck agreed.

“It is, I think, exceedingly easy to define what ought to be understood by national honor; for that which is the best character for an individual is the best character for a nation; and wherever the latter exceeds or falls beneath the former, there is a departure from the line of true greatness.” (Thomas Paine)

This is the third in Wesley Stillwagon’s series on the application of John Steinbeck and Carl Jung’s insights in innovative corporate training program design. To be continued.

A Meeting of Minds on Cannery Row: John Steinbeck’s Phalanx, Carl Jung’s Types, and James Kent’s Gathering Place Roles

Some years ago my paper on John Steinbeck, Carl Jung, the phalanx, and the Development of Higher Management Teams was published by an online forum devoted to the life and work of the Swiss psychologist and psychiatrist Carl Jung. At the time I was developing team and organization building programs for corporations. My job required some business travel. While in California I did what other Steinbeck lovers do: I took a side trip to Monterey’s Cannery Row. What follows further develops my recent post on John Steinbeck, Carl Jung, and how their insights can be applied in business.

Fellow Pilgrims to Cannery Row Discover a Mutual Interest

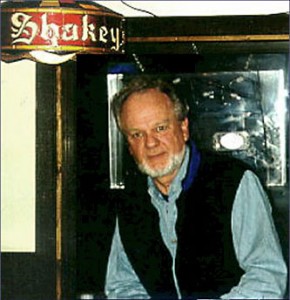

Sometime before my pilgrimage to Cannery Row, I received a call from James Kent (shown below), a John Steinbeck fan who also recognized the practical value of Steinbeck’s work beyond its entertaining read. He told me that he found my phalanx paper and thoughts interesting. We agreed to meet on Cannery Row to talk in person. On a walk down the hallway of our Monterey motel, Jim mentioned his concept of Gathering Place roles and how his team uses it in their initial analysis of informal network gatherings in restaurants, barbershops, and taverns in communities facing challenges. Jim and his team discovered the true nature of public attitudes and resistance within these gatherings beneath the sanitized version frequently presented by public officials. I thought the idea was brilliant and I said so.

I also thought that the concept could be applied in team analysis and building within large organizations—and I still do. This made my connection with Jim and his ideas on Cannery Row that day a particularly fortunate synchronistic experience. If one accepts Jim’s Gathering Place concept, it seems natural to me to consider its relationship to ideas expressed in John Steinbeck’s writing about the phalanx and Carl Jung’s analysis of personal and collective unconscious, functional types, and attitudes.

Steinbeck and Ricketts’ Non-Teleological Way of Thinking

To develop a personally useful understanding of phalanx, one must employ a perspective that does not require a cause-effect relationship common to some scientific research. In other words, with this non-teleological perspective the researchers eliminate the influences of hopes, fears, and expectations in their planning and study. (Please refer to the Pygmalion effect or Rosenthal effect.) Such a perspective enables the researcher to drill through the illusions and brings the subject closer to John Steinbeck’s friend Ed Ricketts’ goal of “true things.” The perspective enables increased objectivity and reduces human subjectivity, projection, and slant. Scientific psychology research has a handicap that is not an issue in other empirical sciences, and that is the study instrument (the individual human psyche) must be used to study individual human psyches. No other science has such a threat to objectivity. As a result, a non-teleological perspective is essential to psychological study objectivity.

In The Log From the Sea Of Cortez, John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts stated the following regarding teleological and non-teleological thinking:

What we personally conceive by the term “teleological thinking,” as exemplified by the notion about the shiftless unemployed, is most frequently associated with the evaluating of causes and effects, the purposiveness of events. This kind of thinking considers changes and cures—what “should be” in the terms of an end pattern (which is often a subjective or an anthropomorphic projection); it presumes the bettering of conditions, often, unfortunately, without achieving more than a most superficial understanding of those conditions. In their sometimes intolerant refusal to face facts as they are, teleological notions may substitute a fierce but ineffectual attempt to change conditions which are assumed to be undesirable, in place of the understanding-acceptance which would pave the way for a more sensible attempt at any change which might pave the way for a more sensible attempt at any change which might still be indicated. Non-teleological ideas derive through “is” thinking, associated with natural selection as Darwin seems to have understood it. They imply depth, fundamentalism, and clarity—seeing beyond traditional or personal projections. They consider events as outgrowths and expressions rather than as results; conscious acceptance as a desideratum, and certainly as an all-important prerequisite. Non-teleological thinking concerns itself primarily not with what should be, or could be, or might be, but rather with what actually “is”—attempting at most to answer the already sufficiently difficult questions what or how, instead of why. An interesting parallel.

The powerful, unconscious, and autonomous influence on individual perception, judgment, conclusions, problem solving, decisions, and behavior, within an objective-focused gathering, group, or MOB, is what John Steinbeck called the phalanx. The MOB objective may be unreasonable or illusory, but may cause members to participate in scape-goating or group bullying of those who simply disagree with their beliefs. I believe there are few things in this life more worthy of scholarly examination than the phalanx phenomenon. The concept is based somewhat on the collective unconscious described by Carl Jung and by other philosophical giants including Harvard Professor William James, a major influence on Jung also familiar to Steinbeck, who coined the term phalanx, clearly defined it, and applied the concept in his novels.

Carl Jung’s Types and Jim Kent’s Gathering Place Roles

Jim Kent’s Gathering Places for friends in a network are casual happenings. (John Steinbeck in Sweet Thursday: “In the Palace Flop house a little meeting occurred—occurred, because no one called it, no one planned it, and yet everyone knew what it was about.”) Informal Gathering Place roles are casually filled without formal election or appointment. I think individual styles role players gravitate naturally to their position. While I have no supportive data for this theory, I honestly believe such research would show that particular roles would naturally be filled by specific functional types—Sensation, Thinking, Intuiting, and Feeling—and attitudes: Extraverted, and Introverted. (There will be much more about the functions, attitudes, and types in my sequel to this article.) In my opinion, for example, Ed Ricketts was an “Introverted Sensation Feeling” type and as a result would fit nicely within Jim Kent’s “Caretaker” role as he specified.

Jim Kent’s Gathering Places for friends in a network are casual happenings. (John Steinbeck in Sweet Thursday: “In the Palace Flop house a little meeting occurred—occurred, because no one called it, no one planned it, and yet everyone knew what it was about.”) Informal Gathering Place roles are casually filled without formal election or appointment. I think individual styles role players gravitate naturally to their position. While I have no supportive data for this theory, I honestly believe such research would show that particular roles would naturally be filled by specific functional types—Sensation, Thinking, Intuiting, and Feeling—and attitudes: Extraverted, and Introverted. (There will be much more about the functions, attitudes, and types in my sequel to this article.) In my opinion, for example, Ed Ricketts was an “Introverted Sensation Feeling” type and as a result would fit nicely within Jim Kent’s “Caretaker” role as he specified.

Of the Introverted Sensation Type, Carl Jung said:

If there were present a capacity and readiness for expression in any way commensurate with the strength of sensation, the irrationality of this type would be extremely evident. This is the case, for instance, when the individual is a creative artist. But, since this is the exception, it usually happens that the characteristic introverted difficulty of expression also conceals his irrationality. On the contrary, he may actually stand out by the very calmness and passivity of his demeanour, or by his rational self-control. This peculiarity, which often leads the superficial judgment astray, is really due to his unrelatedness to objects.

If we include the influence of the Feeling function as an auxiliary to his Sensation type, then we are implying a strong tendency to perceive with a lean toward the interpersonal. This is my opinion based upon what information I’ve read about Ricketts. Jim’s Gathering Place roles are readily summarized and often exemplified in Steinbeck’s fiction, including Cannery Row.

Gathering Place Roles with Examples from Cannery Row

Caretakers

Are the glue that holds the culture together.

Are routinely accessible to people of the networks when they need assistance or advice.

Give assistance or advice freely; there is no chit or payback expected.

Are invisible to outsiders and do not belong to formal groups.

Are essential to high levels of social capital in society.

Ed Ricketts was a Caretaker, as is John Steinbeck’s character, the madam Flora (Fawna).

Communicators

Move information throughout the networks.

Are generally in places where they come into contact with people from various informal networks and formal groups.

Are especially prevalent in gathering places such as coffee shops, bars, beauty shops, restaurants, etc.

Are essential for moving information quickly throughout a community when you need accuracy and word-of-mouth speed.

John Steinbeck’s strike-strategist Mac is a Communicator between networks in In Dubious Battle. In Tortilla Flat Danny is a Caretaker/Communicator; Wing Chung is a Communicator.

Storytellers

Carry the culture through their stories.

Provide a community with the culture benchmarks that are essential to understand how a community can grow and still maintain the good parts of their culture.

Understand the importance of gathering places and are often the “characters” in the gathering places.

George in Of Mice and Men is a Storyteller. Of course the character Doc is cast as a Storyteller in Cannery Row, and the whole Lab actuality functions as a gathering place where stories bring understanding, introspection, reflection, and action.

Gatekeepers

Function as a protective device for the informal systems screening out intrusive people from formal systems.

Narrow the entry to a network or community through information control.

Are often verbal people who understand both the informal and the formal.

Authenticators

Function in the area of knowledge and wisdom.

Have knowledge and wisdom from the culture and often provide cultural interpretations to technical data and information generated by formal systems. Often these individuals have one foot in the cultural context and another in a scientific context understanding both as well as how to integrate so that scientific data can be put into a local context that is usable.

The Seer in Cannery Row is an Authenticator for Doc. Former Ricketts-lab key holder Eldon Dedini operates in this capacity in relation to the real-life lab and its function. Lab gathering place regular Bruce Aris was such a person, as was Ed Ricketts.

Applying the Gathering Place Concept in Your Own Group

I’d like to add my opinion that if one were to include the Jungian concept of Psychological Type to the role definitions, it may become even a more powerful tool than it is. Still, the recognition of the concept was brilliant. Think of an informal gathering of friends. Most of us would predict the likelihood that among the group are individuals filling roles as described by Jim Kent. In any network there are individuals who complement each other and other pairs who grate on each other’s nerves but tolerate the irritation for the good of the fellowship. I believe that there are gathering place role owners who, simply because of their opposing styles, may be irritants to one other. For instance, a Gatekeeper’s style may sharply contrast with that of a Communicator. A preponderance of such interpersonal connections either way will influence the social environment AND the group’s relationship to the phalanx.

Using Carl Jung’s type concept, imagine a role filled by an Introverted Intuitive Thinking type, complete with his or her grand visions, long-term plans, flow charts, logistics, cold and impersonal logic, and another role filled by an Extraverted Sensation Feeling type with interpersonal objectives, stories of previous experiences, etc. They are opposites who can either (1) let petty differences fester to the detriment of the group’s social atmosphere or (2) acknowledge that their negative emotions come out of weaknesses that are contrasted in the persona of the other individual. When this is acknowledged, the two may personally benefit from the awakening, celebrate, and value their complementary styles. The latter possibility will add to the quality of the social atmosphere and will (1) make the group less vulnerable to the negative influences of phalanx and (2) empower the network to strength far beyond its apparent resources.

Photo of James Kent courtesy Wesley Stillwagon.

This is the second in Wesley Stillwagon’s series on the application of John Steinbeck and Carl Jung’s insights in innovative corporate training program design. To be continued.

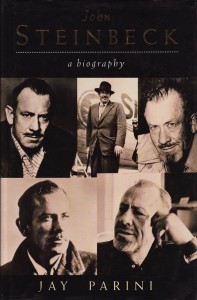

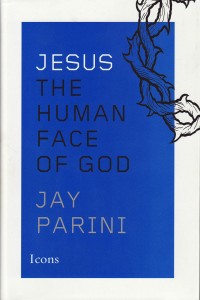

John Steinbeck-Robert Frost Biographer Jay Parini Writes New Life of Jesus Christ

What does Jesus Christ—or John Steinbeck or Robert Frost—really mean to me? John Steinbeck: A Biography by the writer Jay Parini helped me understand why Steinbeck’s life and work spoke to me so powerfully when I first began reading Steinbeck’s books. Robert Frost is another favorite, and Parini—a professor of creative writing at Middlebury College—brought his fellow New England poet’s interior landscape into focus for me with Robert Frost: A Life, his second work of biography. A celebrated Middlebury College faculty member for more than 30 years, Parini has employed his enviable skills as a poet, novelist, and scholar to re-imagine the life of Jesus Christ—the greatest story of them all—in Jesus: The Human Face of God.

What does Jesus Christ—or John Steinbeck or Robert Frost—really mean to me? John Steinbeck: A Biography by the writer Jay Parini helped me understand why Steinbeck’s life and work spoke to me so powerfully when I first began reading Steinbeck’s books. Robert Frost is another favorite, and Parini—a professor of creative writing at Middlebury College—brought his fellow New England poet’s interior landscape into focus for me with Robert Frost: A Life, his second work of biography. A celebrated Middlebury College faculty member for more than 30 years, Parini has employed his enviable skills as a poet, novelist, and scholar to re-imagine the life of Jesus Christ—the greatest story of them all—in Jesus: The Human Face of God.

The new book represents a progression, not a departure, for Parini. John Steinbeck was a lifelong Episcopalian who considered Jesus Christ a moral genius, read and raided the Bible for his fiction, and once thought about writing the screenplay for a Jesus Christ biopic based on the gospels that was never made. Like Robert Frost, Steinbeck valued personal privacy and resisted dogmatic assertions of belief, so we’ll never know how his Christ would have fared on film. For that matter, what do we really know about the details of Jesus’ life from historic records? American writers before and since Steinbeck—including the late Duke University novelist and poet Reynolds Price—have rescripted the Man from Galilee with intriguing angles and uneven results. Now an inspired and imaginative writer from Middlebury College—one of America’s oldest and finest schools—has succeeded where others failed.

Jay Parini: The Man from Middlebury College

Like young John Steinbeck growing up in what became Steinbeck Country, Jay Parini is active in his Episcopal church, located not far from Middlebury College in Robert Frost Country, the home turf of Steinbeck’s New England grandparents. Unlike Steinbeck, Parini is fluent in New Testament Greek; like the author, he knows his Bible and his theology and has explored other traditions—Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism—in depth. But I suspect that none of that is unusual around Middlebury College, long a center of language and cultural studies without equal for its size. Resurrecting Jesus Christ from the tomb of time as Parini has done requires a tool more powerful than scholarship, even the industrial-strength form found in the halls of Middlebury College. Re-mythologizing (Parini’s term) requires an eye for the unseen, an ear for the unknowable, and a writer’s way with words. After three decades of practice writing for mainstream readers, Parini possesses these gifts in abundance. His first collection of poems appeared in 1982. His most recent novel was published in 2010. Four years ago his third novel—The Last Station—became an Academy Award-nominated movie.

Like young John Steinbeck growing up in what became Steinbeck Country, Jay Parini is active in his Episcopal church, located not far from Middlebury College in Robert Frost Country, the home turf of Steinbeck’s New England grandparents. Unlike Steinbeck, Parini is fluent in New Testament Greek; like the author, he knows his Bible and his theology and has explored other traditions—Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism—in depth. But I suspect that none of that is unusual around Middlebury College, long a center of language and cultural studies without equal for its size. Resurrecting Jesus Christ from the tomb of time as Parini has done requires a tool more powerful than scholarship, even the industrial-strength form found in the halls of Middlebury College. Re-mythologizing (Parini’s term) requires an eye for the unseen, an ear for the unknowable, and a writer’s way with words. After three decades of practice writing for mainstream readers, Parini possesses these gifts in abundance. His first collection of poems appeared in 1982. His most recent novel was published in 2010. Four years ago his third novel—The Last Station—became an Academy Award-nominated movie.

Resurrecting Jesus Christ from the tomb of time as Parini has done requires a tool more powerful than scholarship . . . .

Parini’s first venture beyond poetry was his life of John Steinbeck, released in 1994 by Steinbeck’s English publisher (cover image below) and published in the USA in 1995. It was followed by two more literary lives, those of Robert Frost (2000) and William Faulkner (2004), making Jesus Christ Parini’s fourth act biography, a challenging art-form that doesn’t always produce miracles. Among the academically inclined, Parini’s The Art of Teaching (2005) and Why Poetry Matters (2008), plus a host of anthologies, have attracted acclaim. Promised Land: Thirteen Books That Changed America (2008) remains a vade mecum for those exploring the topography of American fiction for the first time. Film adaptations of a pair of Parini novels—Benjamin’s Crossing (1997) and The Passages of H.M. (2010)—are underway. Galliano’s Ghost, another novel, is in progress. So is Conversations with Jay Parini, a University of Mississippi Press publication edited by Michael Lackey. In case you’re counting, that puts him just about where John Steinbeck was at a comparable point in his dizzingly diverse career as a writer.

John Steinbeck: A Life

Like Steinbeck, Parini has his critics. I learned this when I answered a Steinbeck scholar’s recent query. What’s your favorite Steinbeck biography? I replied that I still loved the first one I ever read—John Steinbeck: A Biography. If looks could kill, Parini’s book and I both died that day. Had I spoken heresy? If so, I guess I understand. I too have found reason to quibble with minor points in Parini’s life, published years after another biographer’s much longer book, in my recent research into Steinbeck’s religious roots. But—pardon me—Jesus Christ! Do you want good footnotes or great style? Better than any other biographer I know of John Steinbeck or Robert Frost, Parini sees his subject steadily and sees him whole, telling a creative writer’s story as only a creative writer can. If you’re curious about the time the particular author you’re studying went to the bathroom in his publisher’s office on a given day, be my guest—find the longest biography you can. If you want to know how he recalibrated a certain character, re-imagined a significant scene, or overcame writer’s block to meet a deadline, ask another writer. For John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, Jay Parini more than meets this taste test.

Like Steinbeck, Parini has his critics. I learned this when I answered a Steinbeck scholar’s recent query. What’s your favorite Steinbeck biography? I replied that I still loved the first one I ever read—John Steinbeck: A Biography. If looks could kill, Parini’s book and I both died that day. Had I spoken heresy? If so, I guess I understand. I too have found reason to quibble with minor points in Parini’s life, published years after another biographer’s much longer book, in my recent research into Steinbeck’s religious roots. But—pardon me—Jesus Christ! Do you want good footnotes or great style? Better than any other biographer I know of John Steinbeck or Robert Frost, Parini sees his subject steadily and sees him whole, telling a creative writer’s story as only a creative writer can. If you’re curious about the time the particular author you’re studying went to the bathroom in his publisher’s office on a given day, be my guest—find the longest biography you can. If you want to know how he recalibrated a certain character, re-imagined a significant scene, or overcame writer’s block to meet a deadline, ask another writer. For John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, Jay Parini more than meets this taste test.

Do you want good footnotes or great style?. . . For John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, Jay Parini more than meets this taste test.

Like Steinbeck’s fiction, Parini’s biography of John Steinbeck continues to be popular with readers who are not writing dissertations. I recommend it to anyone interested in learning how Steinbeck developed his craft and overcame his problems. I reread it so often it because it flows so well—unimpeded by anxious over-annotation, syntactical complexity, or current critical cant. Parini’s life of Robert Frost—a natural next subject for a Middlebury College poet-biographer—has the same value for non-natives entering Robert Frost Country for the first time. I’m a Southerner, but I’ll confess that I haven’t read Parini’s biography of William Faulkner, John Steinbeck’s fellow-Nobel Laureate and sometime competitor. My excuse? In graduate school ions ago I studied Faulkner under a meticulous biographer who read from his notes for the prodigious life of Faulkner he was writing. Information without imagination. Not Jay Parini’s problem.

Thinking about Jesus Christ with John Steinbeck in Mind

We can’t know with confidence how Steinbeck’s film Christ would have acted or even looked. But the Jesus brought to fresh life in Parini’s new biography seems just like one of us, only more so. I kept thinking of Steinbeck as I read the book. Though Steinbeck claimed to have no religion (not that odd for an Episcopalian), he disliked reading scripture in any version other than King James, which he knew like, well, the bible. In his new narrative Parini sticks to King James for big stuff like the Beatitudes. But for most of the passages he quotes from or about Christ he provides his own translation—immediate, clear, compelling—in fulfillment of his promise to lift Jesus from the pile of dogma, myth, and demythologizing that have smothered the Christ story. Along the way he quotes other poets, cites other scholars, and acknowledges other teachers at Middlebury College, all without losing momentum or focus for a second. His Jesus Christ is a living teacher speaking in an existential now with something to say to all people. As a believer Parini is passionate about his subject. As a teacher he is careful about his approach. The result? Jesus: The Human Face of God is like a well-taught introductory course in a class of non-majors. No declared religion is required to participate, and doubt is more than welcome. In fact it’s advised.

We can’t know with confidence how Steinbeck’s film Christ would have acted or even looked. But the Jesus brought to fresh life in Parini’s new biography seems just like one of us, only more so. I kept thinking of Steinbeck as I read the book. Though Steinbeck claimed to have no religion (not that odd for an Episcopalian), he disliked reading scripture in any version other than King James, which he knew like, well, the bible. In his new narrative Parini sticks to King James for big stuff like the Beatitudes. But for most of the passages he quotes from or about Christ he provides his own translation—immediate, clear, compelling—in fulfillment of his promise to lift Jesus from the pile of dogma, myth, and demythologizing that have smothered the Christ story. Along the way he quotes other poets, cites other scholars, and acknowledges other teachers at Middlebury College, all without losing momentum or focus for a second. His Jesus Christ is a living teacher speaking in an existential now with something to say to all people. As a believer Parini is passionate about his subject. As a teacher he is careful about his approach. The result? Jesus: The Human Face of God is like a well-taught introductory course in a class of non-majors. No declared religion is required to participate, and doubt is more than welcome. In fact it’s advised.

His Jesus Christ is a living teacher speaking in an existential now with something to say to all people.

The unsmiling Jesus Christ depicted in classic Orthodox iconography (as in the cover image below) seems distant, two-dimensional, hard to embrace, at least for me. Parini’s Jesus, like John Steinbeck’s Ma Joad, is bigger than life but also fully formed, and in the end all-forgiving. The confusing nomenclature of the Bible presents another obstacle to understanding for many. Since I was a kid memorizing the books of the Bible for Sunday school to the time I took the required Old and New Testament courses (both excellent) in college, I’ve felt foggy about biblical names of greater complexity than Paul or Peter and theological ideas more complicated than I Am That I Am. Parini cleared some air in my head.

Parini’s Jesus, like John Steinbeck’s Ma Joad, is also bigger than life but fully formed, and in the end all-forgiving.

For example, I could never keep my Sadducees and my Pharisees straight. No longer! Parini traces the origin of the Sadducees to Saduc, “a legendary high priest from the time of King David,” and describes the group as an easygoing, cultured elite who looked down on their neighbors the Pharisees, seriously doubted the doctrine of bodily resurrection, and deeply enjoyed hobnobbing with foreigners: Episcopalians! The Pharisees? Puritanical, parochial, sure of their salvation—Presbyterians! That confusing half-human, half-divine thing about the true nature of Jesus Christ? Aha! It started with the Romans, maybe earlier. Virgin Birth? Greek and Persian, not Hebrew. Satan? Definitely Hebrew—ha-Satan. Marriage? Jesus Christ was single, but he loved women, knew how to kiss, and produced wine at a wedding over the objections of his mother, a miracle that would have moved a drinker like Steinbeck deeply.

Jesus Christ was single, but he loved women, knew how to kiss, and produced wine at a wedding over the objections of his mother, a miracle that would have moved a drinker like Steinbeck deeply.

In fact, Parini’s Jesus Christ embodies John Steinbeck’s most enviable qualities as a writer and his most admirable aspirations as a man. Listen:

You talked to women without troubling over gender rules. You confronted people about their past lives, their current situation. You didn’t worry about their racial or political origins but sought to bring them into a state of reconciliation with God, a condition of atonement that would fill them with “living water” that reached beyond physical thirst.

Parini’s Jesus Christ loves water, enjoys boats, and is at ultimate ease around fisherman, three constants in John Steinbeck’s sea-sotted life. Jesus is even friendly to tax-collectors (Steinbeck’s father was the county treasurer) and—like Steinbeck—he hated poverty, despised cruelty, and always stuck up for the underdog without starting a war. As Steinbeck, so Jesus: sin is Karma, and it starts inside: “Forgiveness leads to godly behavior”— “anger leads to murderous behavior.” Like Cain and Abel in East of Eden, Parini’s Jesus “takes his listeners back to the origins of murder, anger itself.” Like John Steinbeck in his time, Parini’s Jesus considers affluence a cause of poverty, advising “insane generosity, especially if you love it.” More: “annoy, even outrage, the elite classes. . . .” That’s the mantra Middlebury College had back in my day. I hope it is now. It was certainly Steinbeck’s, starting at Stanford.

Both Jesus and John Made Their Own Myth

Like John Steinbeck, Parini’s Jesus Christ is the maker of his own myth—a slippery term of art in literature that Parini nails down as story. It’s the same meaning Steinbeck had in mind when he resisted the idea of his life story being written while he was still alive, preferring instead to create his own life myth—and not just in novels. So, in his way, with Parini’s Jesus Christ: “One gets the sense that Jesus, knowing the plot of his own story, had arranged everything in advance.” Steinbeck was also skeptical of sudden revolution and instant redemption—much like Parini’s Jesus. Steinbeck on history: Man’s war is with himself. Progress is certain but slow. Peace starts with you. Parini on Christ:

Like John Steinbeck, Parini’s Jesus Christ is the maker of his own myth—a slippery term of art in literature that Parini nails down as story. It’s the same meaning Steinbeck had in mind when he resisted the idea of his life story being written while he was still alive, preferring instead to create his own life myth—and not just in novels. So, in his way, with Parini’s Jesus Christ: “One gets the sense that Jesus, knowing the plot of his own story, had arranged everything in advance.” Steinbeck was also skeptical of sudden revolution and instant redemption—much like Parini’s Jesus. Steinbeck on history: Man’s war is with himself. Progress is certain but slow. Peace starts with you. Parini on Christ:

Recognition takes time, becoming in fact a process of uncovering, what I often refer to in this book as the gradually realizing kingdom: an awareness that grows deeper and more complex, more thrilling, as it evolves.

Parini’s life of Jesus Christ, like the fiction of John Steinbeck, engaged me as a participant, not on the sidelines. Occasionally I got so involved I even wanted to add things, as Steinbeck urges us to do when we participate in his stories and continue them in our lives, where they have their true ending. One example must suffice. Late in the his Jesus story Parini pauses to reflect on the unrecognized irony—“lost on our ears now”—implicit in the name of the rebel Bar-abbas, “son of the father,” freed by Pilate in place of Jesus. How I hoped Parini w0uld stop to savor another, deeper irony, spoken by Christ himself to the Sanhedrin shortly before he’s delivered to the Romans: “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.” Hear what Jesus is saying? Your assumptions are all wrong. Nothing is Caesar’s. Everything belongs to God.

This life reminds this reader why Jesus Christ, like John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, has found an ideal biographer in the churchgoing poet-novelist from progressive Middlebury College. Like Jay Parini, John Steinbeck was a socially-conscious Episcopalian storyteller writing for the multitude. Like Robert Frost, Middlebury College sprang from the soil and salt of Steinbeck’s paternal New England, where Parini makes his home. And Jesus Christ loved us all. This book tells me that Jay does too.

John Steinbeck, Carl Jung, and Phalanx in Tortilla Flat

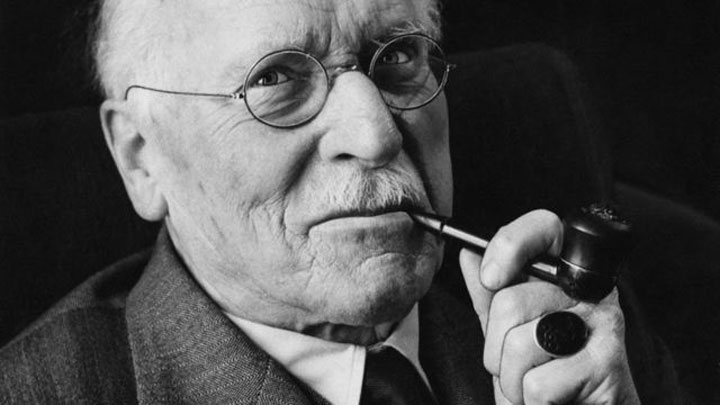

John Steinbeck was ambivalent about psychology. In 1962 he lashed out at his country’s modern “psychiatric priesthood” in Travels with Charley. But 30 years earlier he had stayed up nights discussing the psychological insights of Carl Jung, the great Swiss psychologist-psychiatrist shown here, with Ed Ricketts, Joseph Campbell, and other members of the bohemian Cannery Row circle in the Monterey of his youth. As a result, Jungian principles of a collective human unconscious, the meaning of symbols and myths, and the essential role of certain types of individuals in group behavior inform Steinbeck’s most successful fiction of the 1930s. To a God Unknown and In Dubious Battle are frequently cited examples. As I will show, the insights of Jung in advancing Steinbeck and Ricketts’ phalanx theory are equally evident in Tortilla Flat, the book that launched Steinbeck’s reputation as a promising new writer.

John Steinbeck was ambivalent about psychology. In 1962 he lashed out at his country’s modern “psychiatric priesthood” in Travels with Charley. But 30 years earlier he had stayed up nights discussing the psychological insights of Carl Jung, the great Swiss psychologist-psychiatrist shown here, with Ed Ricketts, Joseph Campbell, and other members of the bohemian Cannery Row circle in the Monterey of his youth. As a result, Jungian principles of a collective human unconscious, the meaning of symbols and myths, and the essential role of certain types of individuals in group behavior inform Steinbeck’s most successful fiction of the 1930s. To a God Unknown and In Dubious Battle are frequently cited examples. As I will show, the insights of Jung in advancing Steinbeck and Ricketts’ phalanx theory are equally evident in Tortilla Flat, the book that launched Steinbeck’s reputation as a promising new writer.

Carl Jung, John Steinbeck, and the Problem of Language

I reached this conclusion not through studying literary theory in a classroom but by reading Carl Jung and John Steinbeck and applying their insights in my three-decade career designing, developing, and leading critical skills and management training programs for corporations such as RCA, KPMG Peat Marwick, Honeywell, AT&T, Blue Cross/Blue Shield of New Jersey, and others. In business, critical skills include tasks where failure to properly perform may cause death, serious injury, or financial loss. Central to the development of cost-effective critical skills training programs in my work was assuring clearly and uniformly understood terms, concepts, and models. To do this, a good instructional designer must define terms and concepts so that training objectives and process are easily communicated and comprehended.

This is usually not too much of a problem in industries and professions that have well-defined lexicons, such as law, engineering, and accounting. It is more difficult when training enters more the ambiguous arena of consulting, marketing, management, and sales. But these activities also require clearly-understood language for personal, interpersonal, team, and group-related tasks. Naturally the field of psychology seems an appropriate place to handle individual, interpersonal, and teaming challenges that arise in the process of doing business and improving outcomes. Yet key terms and basic concepts vary greatly throughout psychology from one school of thought and practice to another. For instance, the essential term ego is defined quite differently by followers of Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud and was ignored completely by later behaviorists such as B.F. Skinner.

Because reliable sources to develop a useful lexicon for applying psychological theories outside the box of clinical psychotherapy are few—and because individual psychologists frequently employ esoteric language and the terms, concepts, and models commonly used are often misunderstood between different schools of psychology—the study and practice of psychology in its various fields and forms is almost universally looked down upon by more precise sciences as fundamentally unscientific. The language problem inherent in psychology is a major reason why empirically-minded biologists and chemists—the sciences that attracted and engaged John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts—continue to hold psychology in low esteem.

Discovering the John Steinbeck-Carl Jung Connection