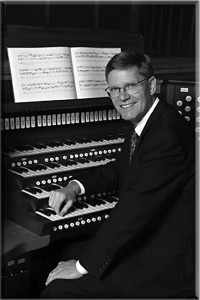

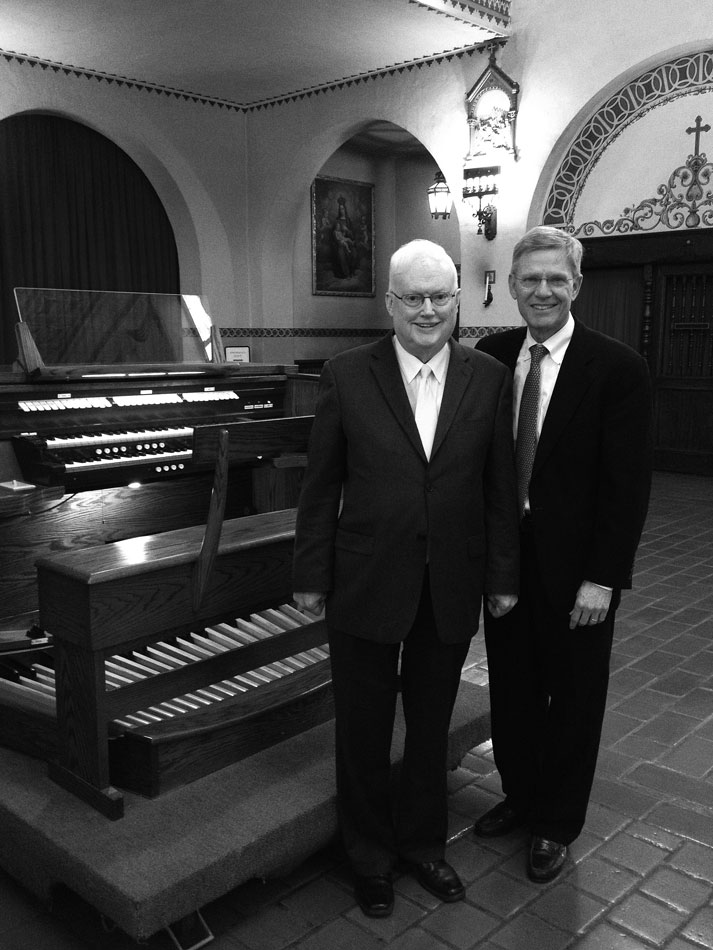

Santa Clara University recently hosted a celebration in sound for the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath at California’s Mission Santa Clara—the world premiere of Steinbeck Suite for Organ by Franklin D. Ashdown (at left in photo), a prolific composer of popular contemporary organ music. As University Organist at Santa Clara University and a fan of Steinbeck’s fiction, I had the pleasure of performing the world premiere of Frank’s work in the program of American organ music that I played to conclude Santa Clara University’s 2014 Festival of American Music on February 16. Inspired by passages from The Grapes of Wrath and Tortilla Flat, Steinbeck Suite for Organ brought the Mission Santa Clara audience—which included Lothar Bandermann, a distinguished composer of orchestral, choral, and organ music who shares John Steinbeck’s German heritage—to its feet. (Scroll down to play audio.)

Santa Clara University recently hosted a celebration in sound for the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath at California’s Mission Santa Clara—the world premiere of Steinbeck Suite for Organ by Franklin D. Ashdown (at left in photo), a prolific composer of popular contemporary organ music. As University Organist at Santa Clara University and a fan of Steinbeck’s fiction, I had the pleasure of performing the world premiere of Frank’s work in the program of American organ music that I played to conclude Santa Clara University’s 2014 Festival of American Music on February 16. Inspired by passages from The Grapes of Wrath and Tortilla Flat, Steinbeck Suite for Organ brought the Mission Santa Clara audience—which included Lothar Bandermann, a distinguished composer of orchestral, choral, and organ music who shares John Steinbeck’s German heritage—to its feet. (Scroll down to play audio.)

Organ Music for The Grapes of Wrath and Randall Ray

Steinbeck’s biographers say that the writer studied piano, sang in choirs, and appreciated organ music, particularly Bach. Since The Grapes of Wrath appeared, the music-minded author’s spirit has inspired almost every kind of music—including Aaron Copland’s musical setting of The Red Pony— except that written for the pipe organ. Thanks to a fan who lives near Santa Clara University and appreciates Frank’s organ music as much as he does Steinbeck’s writing, this condition ended with the commission of Steinbeck Suite for Organ in celebration of The Grapes of Wrath and in memory of Randall Ray, a North Carolinian who admired the novel and visited Steinbeck Country shortly before his untimely death in 2013. Members of the family present for the performance felt that the passages selected by the composer perfectly reflected Randall’s generous spirit and sympathy for the poor.

A World Premiere at California’s Mission Santa Clara

But hearing is worth a hundred words. Listen for yourself by clicking to enjoy each of the five movements of Steinbeck Suite for Organ recorded live on February 16 at Mission Santa Clara—music that reverberates with the pathos and exuberance of Tortilla Flat, The Grapes of Wrath, and John Steinbeck’s humanism. As I explained to the Mission Santa Clara audience, this organ music expresses energy, drama, and transcendence, qualities of Steinbeck’s writing, in colorful cascades of sound that rise and fall with the emotion of the passage being portrayed. Mission Santa Clara was a perfect venue for the world premiere, located on the Santa Clara University campus midway between Steinbeck’s home town of Salinas and San Francisco, the city where he attended opera and concerts as a boy. The program notes excerpted below were provided by the composer in the original organ music score.

I. Preambolo: “The Humanity of John Steinbeck”

In Preambolo, the first movement of this organ suite, Steinbeck’s sympathy for the individual and the common man is represented by the Trumpet stop which sounds a melody similar in character to Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man. As the piece develops, a secondary theme builds to full organ, reflecting the immense influence of Steinbeck’s prose in American culture and politics.

II. Divertimento: The Grapes of Wrath

The Joad family joins a makeshift camp of fellow migrant pilgrims headed on Route 66 for the verdant valleys of California. They enjoy instant community as they trade stories, sit around the camp fire, sing folk songs and gospel songs, and finally join in a spirited square dance.

III. Miserere: The Grapes of Wrath

Ma Joad presents groceries for her large family at the check out counter. The clerk, a man with his own family to feed, cannot extend her credit. But he is sympathetic to her plight and pulls out a dime from his pocket to make up the difference. Miserere creates a somber tone which later brightens in response to the kindness of a stranger.

IV. Musica de los Paisanos: Tortilla Flat

Danny and his friends are a mixed Latino and Caucasian band of brothers living above Monterey, paisonos who spend their days adventuring and drinking booze. Musica de los Paisanos begins with a mellow haze and moves through a patchwork of stylized Spanish and Mexican folk tunes.

V. Toccata: Tortilla Flat

Danny, the central character of Tortilla Flat, inherited two houses. The smaller one, which he gave for the use of his paisanos, burned to the ground due to their carelessness. In a forgiving gesture, Danny let them move into his main home, where they enjoyed rich and colorful camaraderie, like the Knights of the Round Table. But it all ended when Danny died and his main house was consumed by flames. Toccata is emblematic of both houses burning.

Playing the Pipe Organ is a Family Affair

In addition to the world premiere of this piece, my February 16 program at Santa Clara University included organ music by American composers, such as Horatio Parker and Richard Purvis, that Steinbeck might have heard. As noted, the writer took piano lessons as a boy and enjoyed a variety of music, particularly the great American genres of jazz and Broadway, throughout his life. Following Steinbeck Suite for Organ on the Mission Santa Clara program, my son Nicholas, age 15, played the piano part for Clifford Demarest’s Fantasie for Piano and Organ, composed in 1917 when John Steinbeck was the very same age. Nicholas is shown at the far left of the photo with our son Jamison, 14, my wife Deanne, and me. Both boys are high school students in Palo Alto, California, where Steinbeck attended Stanford University. Like the writer John Steinbeck and the composer Frank Ashdown, our sons started piano early, and Nicholas now plays the pipe organ at church, as Frank and I did when we were growing up. Enjoying music was a family affair at the Steinbeck home in Salinas. It is at ours, too.

Recording provided by Santa Clara University with the permission of the composer and the performer. Program notes paraphrased by permission of Franklin D. Ashdown. The Mission Santa Clara pipe organ was built by Schantz Organ Company. Frank Ashdown’s choral and organ music is published by Morningstar, Augsburg Fortress, Alfred, Adoro, Concordia, and others. His distinctive compositions for choirs, pipe organ, and other instruments have been performed in concert halls, churches, and cathedrals including the Mormon Tabernacle, Notre Dame de Paris, and St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. He was born in Utah, grew up in Texas, and lives in New Mexico, where he directs his church choir and composes on an ingenious digital organ, installed in his home, that produces convincing sampled pipe organ sounds.