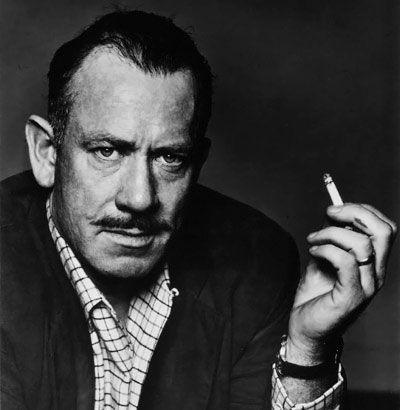

As books from John Steinbeck became popular in the 1930s, Europe armed for war. Like Woodrow Wilson in 1914, Franklin Roosevelt was secretly preparing for America’s entry into international conflict by authorizing domestic surveillance in the name of national security. J. Edgar Hoover was only a foot soldier in Wilson’s campaign against German sympathizers in 1917. By the time Roosevelt issued his secret surveillance authorization order in 1936, Hoover was a veteran of the hunt for German sympathizers and the campaign against suspected communists following the end of the war. By 1935, when he was appointed director of the FBI, Hoover had developed a delicate nose for Americans with German or leftist associations. John Steinbeck had both.

As Roosevelt’s chief domestic spy, Hoover believed in fishing with a big net. He understood the benefits of secrecy, data, and dragnet tactics, and Roosevelt’s executive order authorizing secret domestic surveillance allowed him to exercise his talents in all three areas. As Richard Powers explains the situation in The Life of J. Edgar Hoover: Secrecy and Power, “the domestic intelligence apparatus Hoover assembled for Roosevelt [was] part of the president’s covert preparation against the possibility of war, a secrecy made necessary because of the public’s resistance to any attempt to make it realize the true danger of the international situation.” According to Powers, Hoover became “Roosevelt’s effective, loyal, and indispensable agent.” Steinbeck was devoted to the progressive policies of Roosevelt’s New Deal. Hoover was loyal to the pragmatic president in a more personal and practical way.

Fiction Writer vs. Spy in Chief

The FBI files on John Steinbeck—a fiction writer who upset people without really trying—reflect the differences already noted between Hoover and Steinbeck. Hoover equated patriotism with morality and always wore a suit. Steinbeck dressed and lived casually. Hoover never married. Steinbeck had three wives during his lifetime, and according to FBI files the first registered as a communist in 1937. Steinbeck was pro-labor and always sympathized with the underdog. Hoover was anti-union and gravitated to authority. If Hoover read The Grapes of Wrath when Steinbeck’s novel was published in 1939, he probably didn’t like it. The FBI files document his disapproval of the author’s lifestyle.

Do you suppose you could ask Edgar’s boys to stop stepping on my heels? They think I’m an enemy alien. It’s getting tiresome.

In 1942 Steinbeck wrote the letter that made Hoover an enemy for life. Four years earlier California elected the liberal Cuthbert Olson as governor—the state’s first Democratic chief executive since 1895—and Olson named progressive activists like Steinbeck’s ally Carey McWilliams, author of Factories in the Field, to his new administration. Steinbeck’s sense of political progress in California and America, along with his growing reputation as a fiction writer, helps explain the tone of the note Steinbeck sent to Livingston Biddle, Roosevelt’s attorney general and Hoover’s nominal boss, shortly after Pearl Harbor. Steinbeck wanted an Army commission and someone was getting in his way.

Steinbeck’s note to Biddle named Hoover: “Do you suppose you could ask Edgar’s boys to stop stepping on my heels? They think I’m an enemy alien. It’s getting tiresome.” Like Steinbeck, Hoover was a celebrity, and Steinbeck had visited the White House. As a fiction writer with an eye for character and an ear for speech, he might have predicted Hoover’s response to the attorney general: “I wish to advise that Steinbeck is not being and has never been investigated by this Bureau. His letter is returned to you herewith.” Like James Clapper’s public denial of massive electronic surveillance by the NSA, Hoover’s private answer to Biddle was a lie.

The FBI Files Exposed

Hoover interacted at the highest level with military intelligence and never forgot an insult. His hand in keeping Steinbeck out of the Army is revealed in the FBI files on the author. Although the field agent who investigated Steinbeck concluded that the fiction writer was qualified for a commission, this judgment was overridden by the head of military intelligence. Coincidentally, that secretive group had the James Bondian title G-2—one digit away from the name of the intergovernmental economic group meeting soon in Russia. The Obama White House says that Vladimir Putin’s refusal to extradite Edward Snowden won’t prevent the president from attending G-20. John Steinbeck’s reputation as a fiction writer failed to prevent Hoover’s involvement in the verdict of G-2.

Hoover’s retaliation didn’t stop end in 1942. As the FBI files show, books from John Steinbeck and reviews by unfriendly critics were scoured for signs of disloyalty, beginning with The Grapes of Wrath and ending with the author’s last novel, The Winter of Our Discontent.. Agency-inspired citizen-complaint letters contained in FBI files cited Steinbeck’s visits to Russia—both before and after World War II—in impugning the author’s patriotism. Anything remotely connected to Steinbeck’s past went into the FBI files, including fictitious findings by the American Legion Radical Research Bureau, a right wing organization founded during the Red Scare following World War I. Steinbeck was one fiction writer who avoided the reach of McCarthy’s paranoid committee on un-American activities, but he never dropped off the radar screen of Hoover’s FBI.

I wish to advise that Steinbeck is not being and has never been investigated by this Bureau. His letter is returned to you herewith.

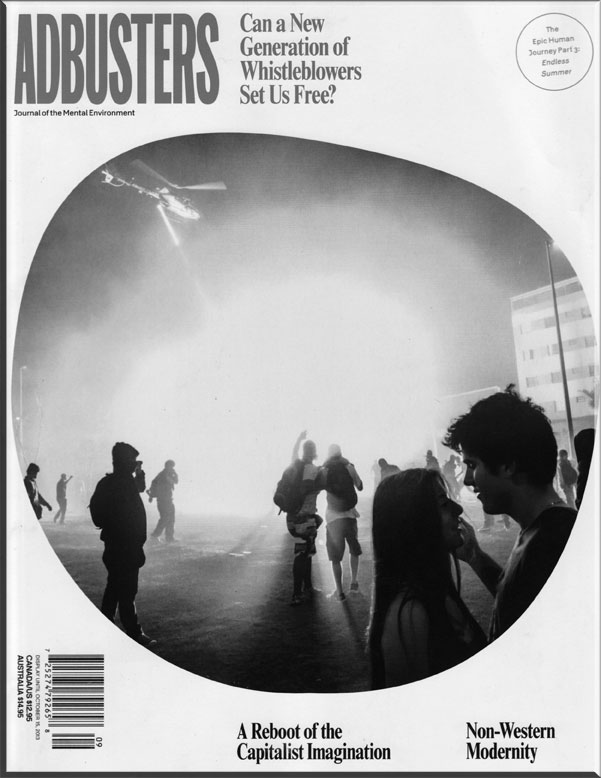

J. Edgar Hoover’s private war on America’s foremost fiction writer—a paper war fought with letters, memos, and clippings—was eventually exposed in Top Secret: The FBI Files on John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch and published in 2002. Hoover died without achieving anything more damaging to Steinbeck than keeping the author out of the Army. In its 75th year, The Grapes of Wrath remains an international icon. Forty years after his death, Hoover has congealed as a symbol of government secrecy and non-judicial overreach detestable to generations of dissenting Americans, beginning with John Steinbeck and continuing in Edward Snowden.

To paraphrase Disraeli on Darwin, Steinbeck was on the side of the whistle-blowers, both as a fiction writer and as a citizen. How Steinbeck would envision the ending of Snowden’s saga is of course unknowable. Given the author’s distrust of Russian dictators, however, it’s safe to assume he wouldn’t like the middle part of the story as it’s unfolding. How we participate in Snowden’s narrative—to paraphrase the fiction writer—is entirely up to us.

Read more in Steinbeck, Snowden, and the Future of America.