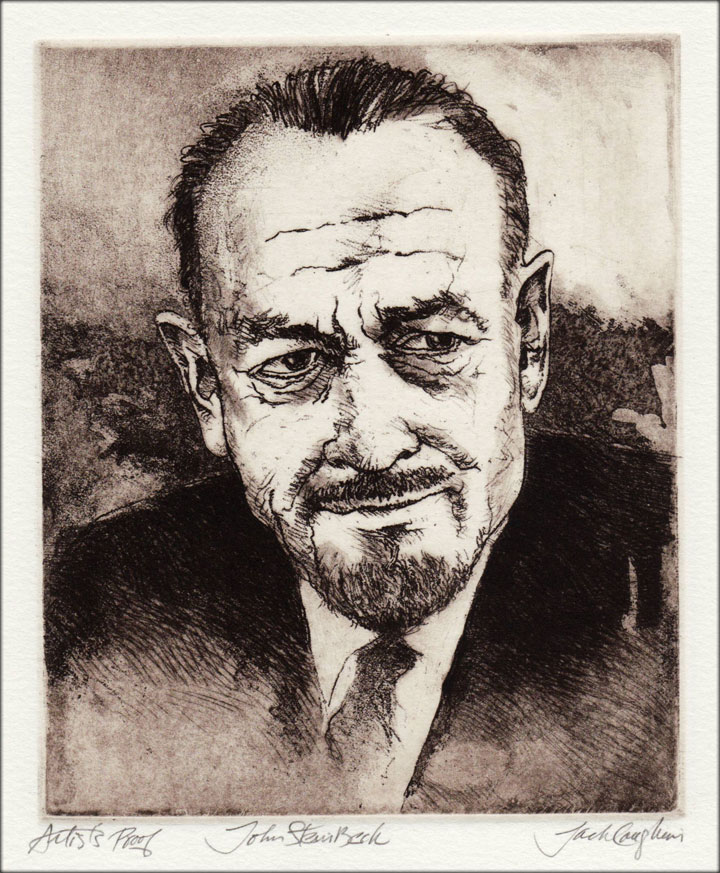

Google “Bernie Sanders-Georgetown University” for proof that John Steinbeck still matters. Sanders, the progressive Senator from the State of Vermont who is running for President of the United States, echoed Steinbeck’s greatest novel and channeled Franklin Roosevelt, Steinbeck’s favorite President, during a passionate speech to students at Georgetown University on November 19. Advertised as “Sanders on socialism,” the hour-long address called for the enactment of an “economic bill of rights” for all Americans, first envisioned in 1944 by Franklin Roosevelt in a speech delivered not long before Roosevelt died. In it Roosevelt said that true freedom requires economic security for everyone: the right to a decent job at a living wage, adequate housing, and guaranteed healthcare. Sanders agrees, adding freedom from corrupt campaign financing to Roosevelt’s litany of change. Steinbeck, a lifelong Democrat, met Franklin Roosevelt on several occasions, and Eleanor Roosevelt became an ally and, later, a friend. But in 1944 Steinbeck felt disappointed with America and depressed about the future. His experience reporting from Italy on World War II shook him badly, his domestic life was a mess, and his best period as a writer of socially conscious fiction lay in the past. His siblings were Republicans and he was trying to go home again.

Bernie Sanders, the progressive Senator from the State of Vermont who is running for President of the United States, echoed Steinbeck’s greatest novel and channeled Franklin Roosevelt, Steinbeck’s favorite President, during a passionate speech to students at Georgetown University on November 19.

Still, Steinbeck’s writing of the 1930s is evidence that, if asked, he would have supported Roosevelt’s economic bill of rights in 1944. Steinbeck’s 1939 masterpiece, The Grapes of Wrath, dramatizes the same Depression-era America that Roosevelt described in his 1937 inaugural address as “ill-housed, ill-clad, and ill-nourished.” Sanders quoted Roosevelt’s 1937 line at Georgetown University, building his case on Roosevelt’s policies and employing statistics to back up his assertion that Americans are underemployed, over-incarcerated, and sicker than they should be, despite unprecedented national wealth. Alone among the current crop of candidates in either party, he views the growing gap between rich and poor as a moral outrage equivalent to the Great Depression, one that requires legislative remedy through political revolution. Sanders began his hour-long speech at Georgetown University in anger but closed in hope. He called for political revolution on the Franklin Roosevelt model, but he also gave shout-outs to Martin Luther King, Jr., Lyndon Johnson, and King Abdullah of Jordan in his position statements on foreign and domestic affairs. Judging by audience response, his listeners got the message, and his biggest applause lines were worthy of John Steinbeck: black lives matter, social injustice is evil, and immigrants make America strong.

“Corporate media” ranks high on Bernie Sanders’s list of oligarchies to be overthrown by breakup, along with Wall Street banks, drug manufacturers, and the billionaires who buy elections. As a result, the mainstream coverage of his campaign to date has been biased, misleading, and focused on surface rather than substance. Despite its depth and drama, his Georgetown University address—the most detailed articulation of his views so far—was no exception. News stories about the speech the next day were as scarce as copies of The Grapes of Wrath in Kern County, California. When TV talking heads deigned to mention Sanders’s revival of Roosevelt’s economic bill of rights, most mumbled “socialism” before moving on to friendlier content: Hillary Clinton’s emails, Donald Trump’s demand for the deportation of undocumented Mexicans, and Ted Cruz’s call for closing America’s borders to Muslims in response to the terrorist attacks in Paris. Like John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath, Bernie Sanders’s campaign has stirred deep animosity within power structures that control the system. They hate being exposed, and as Steinbeck learned they fight back.

Like John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath, Bernie Sanders’s campaign has stirred deep animosity within power structures that control the system. They hate being exposed, and as Steinbeck learned they fight back.

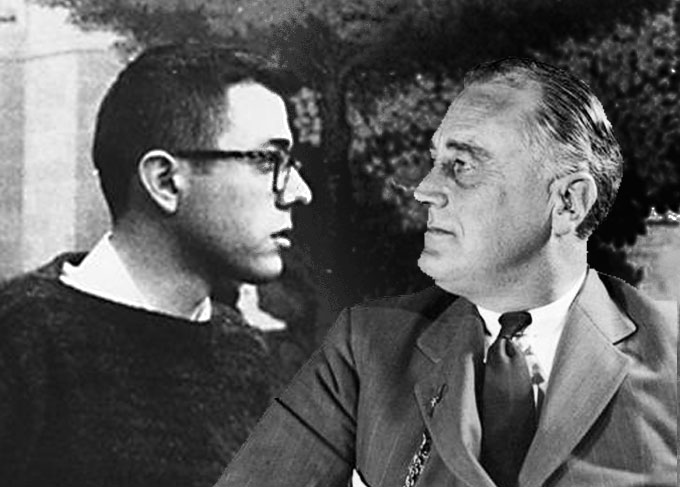

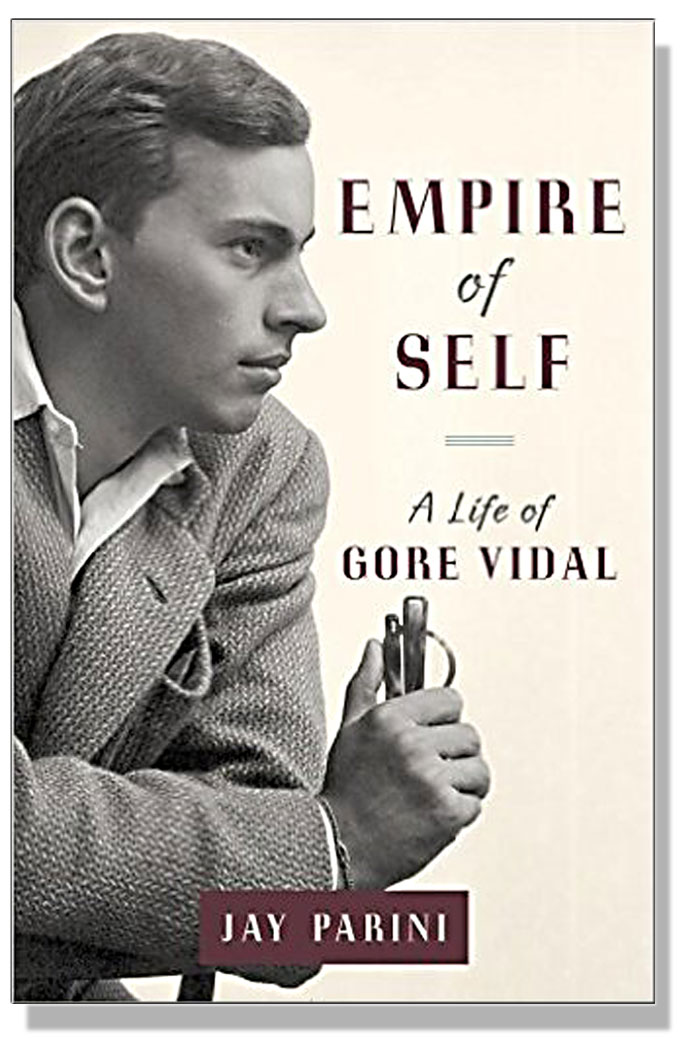

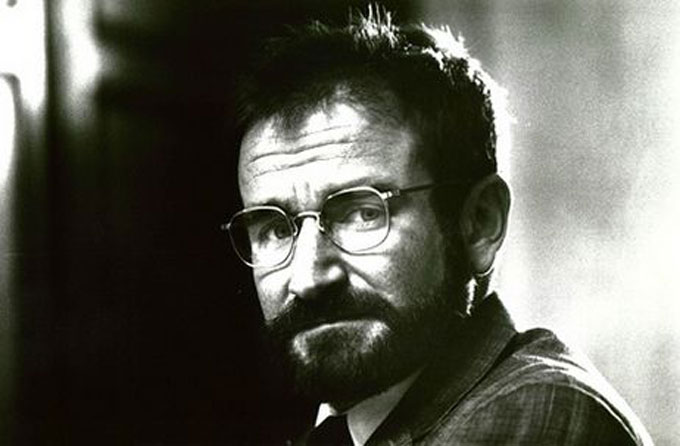

They called Steinbeck a communist. Sanders, like Roosevelt, they dismiss as a socialist. A plum-toned aristocrat sometimes described as a traitor to his class, Roosevelt fought “economic royalists” from both parties and welcomed their scorn. Sanders, who comes from Brooklyn and faults Democrats for acting like Republicans, admires Roosevelt’s attitude and quotes him frequently, as he did at Georgetown University. Compared with Roosevelt, however, Sanders is a roughneck speaker who still sounds like a New Yorker. He said “crap” early in his remarks at Georgetown University and admitted that, like Steinbeck at Stanford, he didn’t apply himself as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago in the early 1960s (see photo). In the 1950s Steinbeck supported Adlai Stevenson, a polished and erudite Illinois progressive who lost two elections to Dwight Eisenhower, a man with a vocabulary so limited that Steinbeck said it disqualified him from being President. During the period Bernie Sanders was demonstrating for desegregation rather than doing his homework at the University of Chicago, Steinbeck’s political affections moved on to Lyndon Johnson, an unpolished President who talked tough while reviving Roosevelt “socialism” in landmark legislation—civil rights, Medicaid, Medicare—that Sanders praised in his November 19 address. The dead no longer vote, but if Steinbeck were alive today I think his big heart would be with Bernie Sanders. Watch the video of Sanders’s Georgetown University speech and see if you agree: