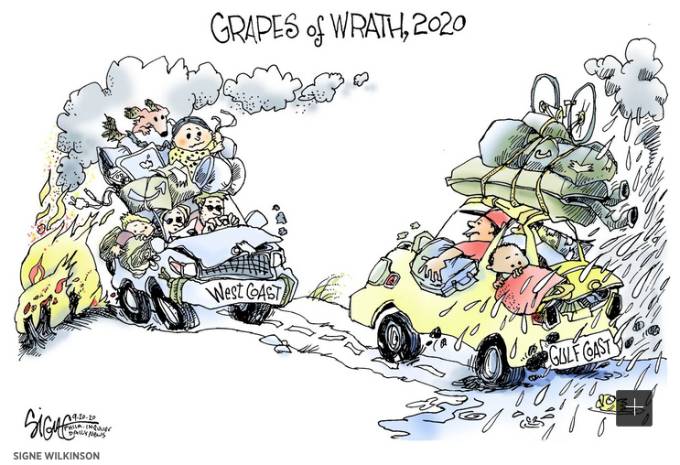

America’s cancel-culture movement has caught up with the school district of Newfane, the rural community in upstate New York where a student named Madison Woodruff complained recently about having to read John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, the 1937 novella-play in which the writer explored racism, sexism, and ageism in rural California 100 years ago. A February 2, 2021 report in the Lockport Union Sun & Journal gives the 16-year-old’s reason for objecting to a book that might make her “uncomfortable”: “My main concern is that kids are feeling uncomfortable, and I feel uncomfortable, and I feel if you’re reading a book in school, where school is supposed to be a safe place, you can’t make kids feel uncomfortable because of a book we’re reading.” Citing the December 2020 decision by school district officials in Mendota Heights, Minnesota to remove Of Mice and Men (“the second most frequently banned book in the public school curriculum in the 1990s”), following complaints by parents and staff at Henry Sibley High School, the report quotes Newfane’s high school principal statement in response to Woodruff: “literature is a way to ‘confront’ bigotry.”

Like Shakespeare, John Steinbeck Can Create Discomfort

Also quoted in the article is Nick Taylor, director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies and professor of English at San Jose State University, who defended Steinbeck’s right to be candid and the reader’s right to be uncomfortable. “She’s absolutely justified in having these feelings,” said Taylor: “I think Steinbeck would’ve said she was completely justified, though he would’ve added, ‘And that’s entirely my point.” Two days after the report appeared, the paper published a letter from a former student who credited her Newfane English teacher with introducing her to another comfort-challenging author: “I always felt safe in school no matter what our assignment was. I had a brilliant English teacher and when I was Madison’s age he introduced us to Shakespeare, who wrote comedies, tragedies, sonnets and poems, and historical works. Shakespeare is the most-recognized playwright in the world. His works could make you feel uncomfortable if you chose to interpret them that way.”

Also quoted in the article is Nick Taylor, director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies and professor of English at San Jose State University, who defended Steinbeck’s right to be candid and the reader’s right to be uncomfortable. “She’s absolutely justified in having these feelings,” said Taylor: “I think Steinbeck would’ve said she was completely justified, though he would’ve added, ‘And that’s entirely my point.” Two days after the report appeared, the paper published a letter from a former student who credited her Newfane English teacher with introducing her to another comfort-challenging author: “I always felt safe in school no matter what our assignment was. I had a brilliant English teacher and when I was Madison’s age he introduced us to Shakespeare, who wrote comedies, tragedies, sonnets and poems, and historical works. Shakespeare is the most-recognized playwright in the world. His works could make you feel uncomfortable if you chose to interpret them that way.”

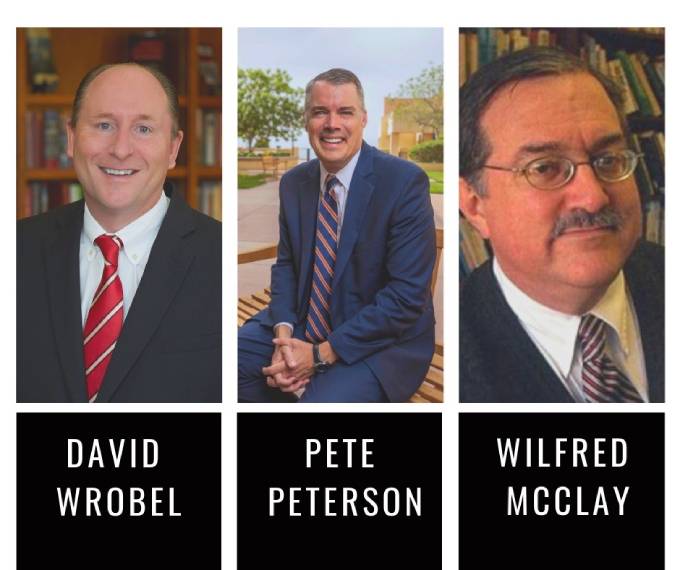

Lead photo: Lon Cheney and Burgess Meredith as George and Lenny in Lewis Milestone’s 1939 film version of John Steinbeck’s 1939 classic. Photo of Nick Taylor courtesy Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies.