It was a slog at times, and Ernest Hemingway the man repeatedly came off as a really unlikable jerk, but I made it through Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s Hemingway fest on PBS. Boy, was Hemingway a strange, mean, and multi-troubled soul. By comparison, he makes John Steinbeck’s grumpy persona look saintly.

There are interesting parallels between Hemingway and Steinbeck, though, especially their struggles with booze/drugs, their need to prove their manhood in war, and their rocky marriages and fatherhood failings. They were also equally terrified of speaking in public or on TV. Hemingway’s fame and influence surpassed Steinbeck’s and every other writer before and after World War II. But it was odd that Novick and Burns never mentioned Steinbeck at all.

Scott Fitzgerald had a few cameos. The name John Dos Passos was dropped. But you would have thought Hemingway was the only important American novelist alive after 1938.

Hemingway’s Action “Unnecessarily Cruel and Stupid”

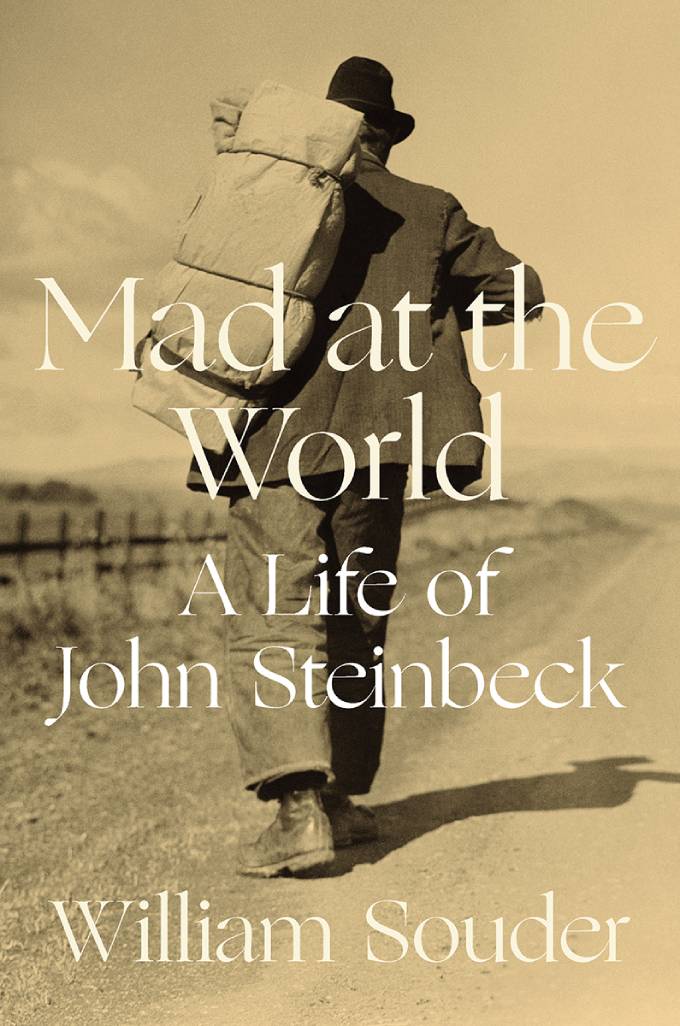

Burns could have slipped Steinbeck into the program—and provided a redundant example of what an ass Hemingway was—by mentioning the only meeting between the two literary heavyweights. As Jackson Benson describes it in his biography, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, Hemingway expressed the wish to meet Steinbeck in the spring of 1944 when they were both in New York City.

It must have been quite an event. The dinner party at Tim Costello’s on Third Avenue took weeks to arrange, was attended by Robert Capa (at left in World War II photo with Army driver and Hemingway, right), John O’Hara, and John Hersey and—says Benson—turned out to be pretty much a disaster. The only memorable incident was when Hemingway and O’Hara were at the bar arguing over the authenticity of the old blackthorn walking stick Steinbeck had given O’Hara. As Benson tells the story, to prove that the walking stick—which had been handed down to Steinbeck by his grandfather—was not the real deal, Hemingway bet O’Hara 50 bucks he could break it over his head.

“O’Hara accepted,” Benson writes. “Hemingway took the stick by both ends and pulled it down over his head, breaking it in two. ‘You call that a blackthorn?’ he said, and threw the pieces aside. O’Hara was mortified, while Steinbeck . . . looked on and thought the whole thing was unnecessarily cruel and stupid.”

Benson says Steinbeck admired Hemingway more than any other writer of his time. But it was Hemingway’s writing skills Steinbeck admired, not his creepy he-man personality. Based on Burns and Novick’s six-hour biography, Steinbeck had it right.

Ken Burns received the 2013 John Steinbeck award for humanitarian achievement given by the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University. Michael Katakis—a consultant and major contributor to the Hemingway film—is an essayist, fiction writer, and photographer who divides his time between Paris, London, and Carmel, California. Bill Steigerwald recently released the e-book version of his book on Ray Sprigle, which includes the original 21-part series reporter Sprigle wrote about his undercover journalism mission in the Jim Crow South in 1948.—Ed.