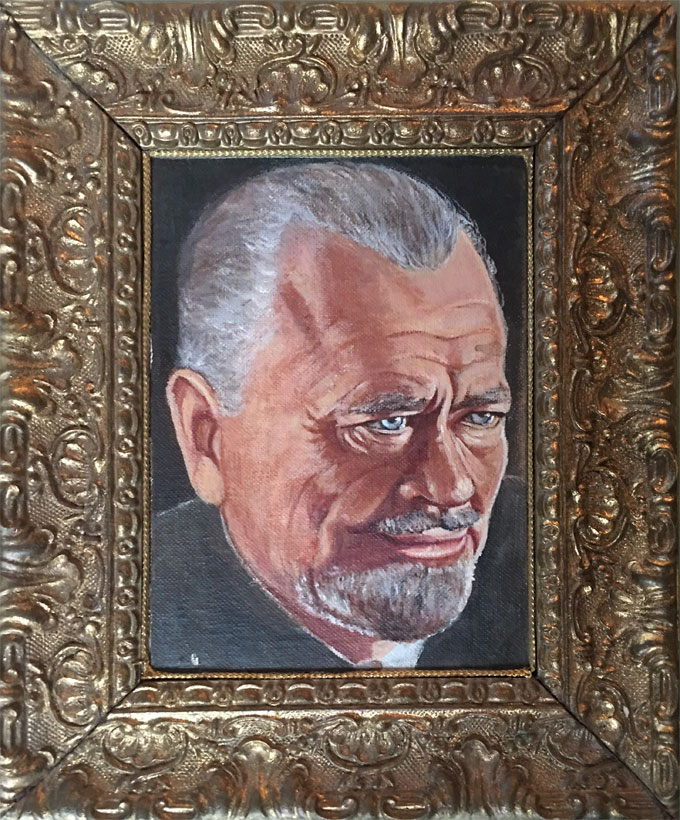

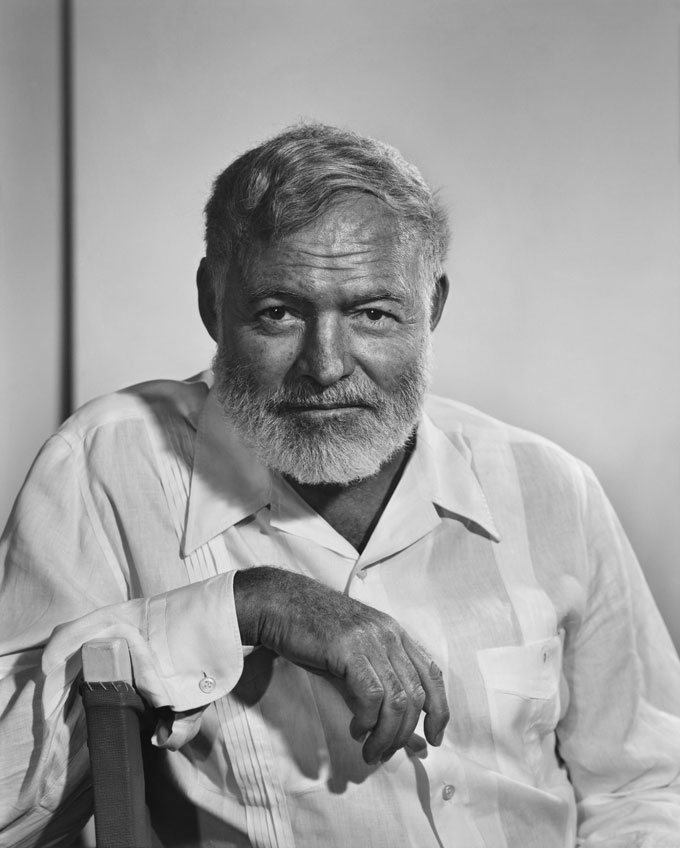

The lucky purchase by a young couple in Austin, Texas—of a lost portrait of John Steinbeck painted by an admirer 50 years ago—presents intriguing questions about the California author’s connection to Texas, the state he celebrated in Travels with Charley because, he said, his wife Elaine grew up there. Anthony Verdecanna, a specialist in mid-20th century furniture, and his wife Whitney, a musician, came across the elegantly framed find recently at an estate sale near Austin. The inscriptions on the back—“To Elaine Steinbeck” and “Virginia Boyd in Thailand 1969”—piqued their curiosity about its provenance. Following the trail of “Jenny Boyd,” the person who signed the work, they learned that the Virginia in the inscription was most likely the artist’s mother, Virginia Hawkins Boyd Connally, a pioneering physician in Abilene and the widow of Ed Connally, chairman of the Texas Democratic Party during the heyday of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson. An eye-ear-nose-and-throat specialist whose first husband

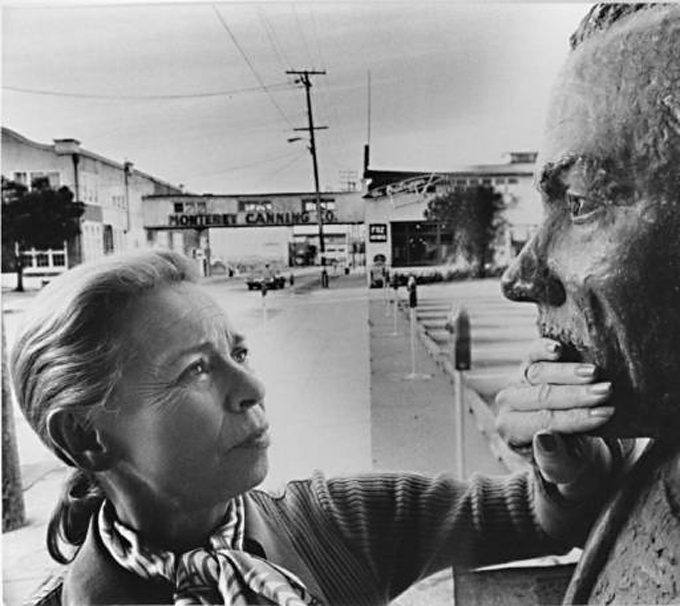

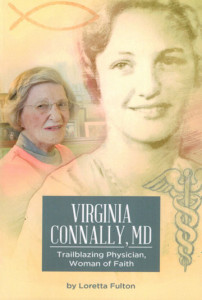

The lucky purchase by a young couple in Austin, Texas—of a lost portrait of John Steinbeck painted by an admirer 50 years ago—presents intriguing questions about the California author’s connection to Texas, the state he celebrated in Travels with Charley because, he said, his wife Elaine grew up there. Anthony Verdecanna, a specialist in mid-20th century furniture, and his wife Whitney, a musician, came across the elegantly framed find recently at an estate sale near Austin. The inscriptions on the back—“To Elaine Steinbeck” and “Virginia Boyd in Thailand 1969”—piqued their curiosity about its provenance. Following the trail of “Jenny Boyd,” the person who signed the work, they learned that the Virginia in the inscription was most likely the artist’s mother, Virginia Hawkins Boyd Connally, a pioneering physician in Abilene and the widow of Ed Connally, chairman of the Texas Democratic Party during the heyday of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson. An eye-ear-nose-and-throat specialist whose first husband  was named Fred Boyd, Dr. Connally was born in 1912 and died on March 31, 2019, leaving her daughter Genna Boyd Davis, an art education major in the 1960s, as her sole immediate survivor. Like a story by Steinbeck, the heroic narrative of Virginia Connally’s life presents multiple possibilities. Did she and Ed meet John and Elaine in Texas through the Johnsons, with whom the Steinbecks were friendly? Or was the writer’s generous portrait of Texas in the pages of Travels with Charley enough to win her affection—and the tribute of a devoted daughter’s painting, lost for 50 years until its discovery by yet another power couple from Elaine Steinbeck’s home state?

was named Fred Boyd, Dr. Connally was born in 1912 and died on March 31, 2019, leaving her daughter Genna Boyd Davis, an art education major in the 1960s, as her sole immediate survivor. Like a story by Steinbeck, the heroic narrative of Virginia Connally’s life presents multiple possibilities. Did she and Ed meet John and Elaine in Texas through the Johnsons, with whom the Steinbecks were friendly? Or was the writer’s generous portrait of Texas in the pages of Travels with Charley enough to win her affection—and the tribute of a devoted daughter’s painting, lost for 50 years until its discovery by yet another power couple from Elaine Steinbeck’s home state?