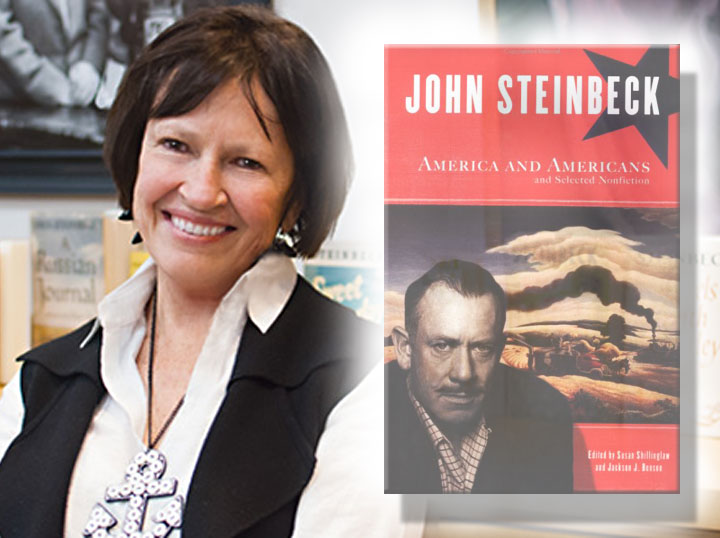

In observance of the anniversary of John Steinbeck’s death on December 20, 1968, the International Society of Steinbeck Scholars invites proposals for papers exploring Steinbeck’s continued relevance, 50 years later, to be delivered at the organization’s May 1-3, 2019 conference at San Jose State University. “Steinbeck and the 21st Century: Identity, Influence, and Impact” is sponsored by the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies and will take place at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library in downtown San Jose, California. According to Nick Taylor, the center’s director, proposals for papers are welcome from a wide variety of disciplines, including literary and cultural studies as well as ecology and pedagogy, and may encompass the comparative examination of Steinbeck and 21st century authors, issues surrounding the reception and translation of Steinbeck’s books in the 20th century, and commentary on Steinbeck’s writing from the perspective of movements like #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and organized resistance to the mistreatment of migrants and refugees in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East. Also of interest is how classroom teachers today use Steinbeck to engage students on social issues, popular culture, and artistic expression. Travel funding is available for students whose papers are accepted. For details visit the conference web page.

As of today’s post we are temporarily suspending weekly posts at SteinbeckNow.com to pursue a print project requiring attention. We will continue to respond to email inquiries, curate comments, and post news about opportunities like this one, and we will review guest-author submissions in the order they are received when we resume weekly publication. Thank you for your understanding and cooperation.—Ed.