As I was planning a trip from Virginia to California to visit my family in late February, I decided to add a two-day excursion to Salinas and the Steinbeck National Center. Shortly before I left, my eye was caught by a poetic tribute to Edgar Allan Poe at Steinbeck Now.com, an author website that had only recently come to my attention. Poe initially sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Now John Steinbeck has reignited my torch.

As I was planning a trip from Virginia to California to visit my family in late February, I decided to add a two-day excursion to Salinas and the Steinbeck National Center. Shortly before I left, my eye was caught by a poetic tribute to Edgar Allan Poe at Steinbeck Now.com, an author website that had only recently come to my attention. Poe initially sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Now John Steinbeck has reignited my torch.

Poe sparked my interest in closely examining great American authors. Steinbeck reignited my torch.

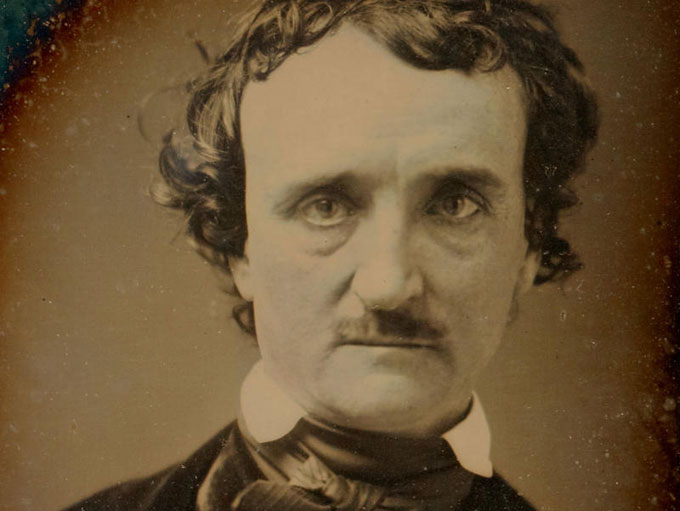

At my website LitChatte.com I have identified Poe as the first of a line of great American literary writers who portray American history imaginatively. While acknowledging that John Steinbeck continued the tradition, I was surprised to find a poem about Poe on an author website devoted to a writer best known for fiction. Though I can’t say that Roy Bentley’s poem is a fair portrayal of Poe—a pioneer who contributed to the advancement of American literature and the vocation of John Steinbeck—reading it reminded me that both writers were trashed by misinformed critics when their works first appeared and again when they died. Steinbeck was called a communist and a liar and his characters were deemed two-dimensional when The Grapes of Wrath was published. At the National Steinbeck Center I learned that copies were burned in Salinas and banned from schools and libraries around America, despite Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize.

I was surprised to find a poem about Poe on an author website devoted to a writer best known for fiction.

Similarly, Poe’s character and work were maligned by critics in his day, most harshly by Rufus Griswold—a contemporary who served as one of Poe’s principal editors—in The Poets and Poetry of America, an anthology edited by Griswold, and in an unsympathetic obituary of Poe that Griswold wrote under a pseudonym. The existing tension between the two men was exacerbated when Poe took exception to Griswold’s inclusion and omission of certain poets after the anthology appeared in 1842. Griswold retaliated by trashing Poe’s personal life in the October 9, 1849 New York Daily Tribune obituary he signed “Ludwig.”

Like Steinbeck, Poe’s character and work were maligned by critics in his day, most harshly by Rufus Griswold.

It didn’t take much detective work to determine that “Ludwig” was Griswold, a conniver who gained a stranglehold on future publication of Poe’s work (by usurping the role of Poe’s literary executor from Poe’s living relatives) and who damaged Poe’s reputation by falsely claiming that he “had few friends.” Halfheartedly conceding that “literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars,” Griswold’s obituary portrayed Poe as a vagabond who moved pointlessly between Baltimore, Richmond, New York, and Philadelphia, even though Griswold worked at different times in the same cities—the only literary centers where a struggling writer (or editor) could hope to make a living in the first half of the 19th century.

Griswold’s obituary portrayed Poe as a vagabond who moved pointlessly between the only literary centers where a struggling writer could hope to make a living.

With each move, Poe developed an essential pillar of his versatile career as a professional writer, one which became a vocational model for later authors, like Steinbeck and Twain, who used their journalism to inform and inspire their literary creations. Griswold’s “Ludwig” obituary also spread the myth that Poe was a hopeless alcoholic and a madman, and it predicted that neither he or his writing would be long remembered. Time has disproved Griswold’s prophecy, and Griswold’s claims about Poe’s character and behavior have been discredited by serious scholars, though unwitting writers continue to base their assumptions about Poe on Griswold’s intentional misdirection.

With each move, Poe developed an essential pillar of his versatile career as a professional writer who used journalism to inform literary creation.

Reliable information can be found at the author website founded by the Poe Society, which points the reader to The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, by Dwight Thomas and David Jackson. A comprehensive account of Poe’s professional and personal activities, it documents Poe’s friendships, and the position of respect he held in social circles where he was known. Though Poe wrote masterpieces of horror, he wasn’t mad, and the state of inebriation noted by others may well have been caused by acute sensitivity to alcohol, small amounts of which made him sick and appear drunk. Poe’s drinking was limited to social situations where gentlemen were expected to imbibe. A disciplined writer (there are no credible accounts of drinking while writing), Poe was devoted to his young wife Virginia, whose death a few years before his own contributed to his emotional and physical deterioration.

Though Poe wrote masterpieces of horror, he wasn’t mad, and the state of inebriation noted by others may have been caused by acute sensitivity to alcohol.

The true picture of Poe’s life explains why the poem at SteinbeckNow.com concerned me. It opens by suggesting that Poe could or would have downed “thirteen insipid whiskeys,” a preposterous proposition, despite the clever pun on “insipid.” (From what we know about his clinical condition, it’s likely he would become disoriented after the first drink and pass out after the second.) The elusive line “A joke is to say what its poets are to America” reflects a viewpoint advanced by Griswold in his anthology, and the reference to Poe’s strained relationship with his “foster father” John Allan, who “left him nothing,” repeats a misconception about Poe’s later behavior. Having dropped Allan’s name, he worked hard to provide for himself and his wife. He was prolific and his work sold well abroad. But lax copyright laws failed to protect writers’ interests in 19th century America, and Poe suffered the consequences.

Poe was prolific and his work sold well abroad. But lax copyright laws failed to protect writers’ interests in 19th century America, and Poe suffered the consequences.

Mark Twain learned from Poe’s experience and eventually self-published. Copyright laws improved in the 20th century, and writers like John Steinbeck (who also had a more supportive father) lived to achieve the financial security denied to Poe. Roy Bentley’s poem may have been intended as a tribute, but it fails to reflect the facts of Poe’s life, or Poe’s contribution to the progress of American literature. Instead of shedding new light on a sympathetic subject, it continues the slight to Poe’s reputation consciously created by Rufus Griswold, who knew that “a story will circulate” once it’s invented. Though eloquent, the last line of the poem (“If God exists, it isn’t to love poets”) regrettably reinforces that unfortunate conclusion.