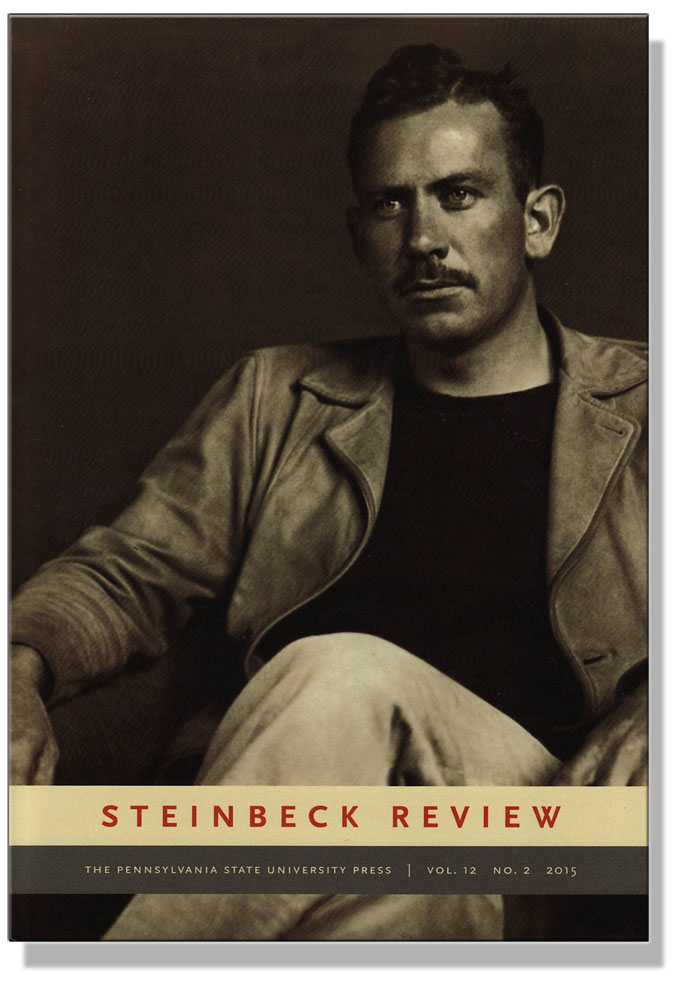

Who said literary criticism is just for critics? Not the editors of Steinbeck Review. The winter 2015 issue proves that San Jose State University, the journal’s publisher, embraces diversity in many forms, and that its editors are willing to let non-critics play the specialist’s game. Among the current contributors are (1) a graduate student in history from Canada, (2) a former college film teacher, (3) a retired biology professor and dean living in Oregon, (4) a Steinbeck fan from California’s Central Valley, and (5) the W.W. Kellogg Professor of Agriculture, Food and Community Ethics at Michigan State University. But the unlikeliest candidate in the intriguing mix may be Daniel Levin, a pharmaceutical research executive with a Ph.D. in chemistry from Cambridge University who now lives in California. Prompted by a visit to the National Steinbeck Center and curious about apparent discrepancies between an exhibit there and Steinbeck’s Hebrew in East of Eden, Levin took a scientific approach, consulting Talmudic sources, Steinbeck curators, and a Hebrew language adviser to investigate Steinbeck’s adaptation of the term timshol from the Genesis story about Cain’s banishment, east of Eden, after he kills his brother Abel. “John Steinbeck and the Missing Kamatz in East of Eden: How Steinbeck Found a Hebrew Word but Muddled Some Vowels,” the result of Levin’s exemplary study, demonstrates why, for lovers of John Steinbeck, literary criticism is too important to be left to professional literary critics. See for yourself. Subscribe to Steinbeck Review.

Archives for December 2015

Setting the Stage for John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath: Richard Henry Dana at 200

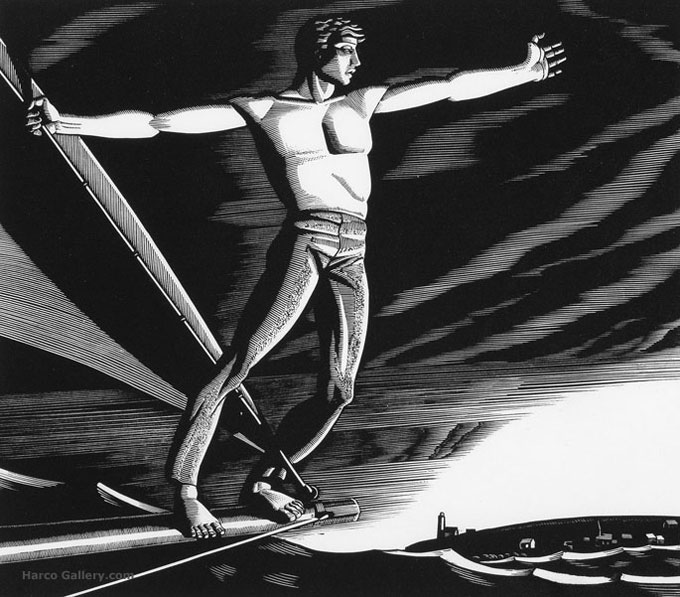

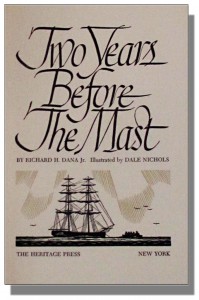

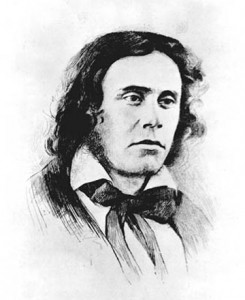

Richard Henry Dana, Jr., the author of Two Years Before the Mast, was born 200 years ago in Massachusetts, the home of Dana’s famous Founding family, and of John Steinbeck’s paternal grandparents as well. Growing up, Steinbeck read Dana’s autobiographical account of life along the California coast in the early 19th century–as noted by the artist Tom Killion, the earliest writing, in English, that describes the California coast from the perspective of the sea. New England roots, adventure fiction, California coast: cause enough for Steinbeck fans to celebrate Richard Henry Dana’s bicentennial. But Two Years Before the Mast is also a masterpiece of social-protest literature, like The Grapes of Wrath, and helped set the stage for Steinbeck’s novel. Details of Dana’s life are worth mentioning in 2015, two centuries after his birth and 75 years since the appearance of The Grapes of Wrath. They connect Dana’s era and output with those of Steinbeck—and with the New England artist Rockwell Kent, who wrote popular books of travel, illustrated books by others (including Moby Dick, above), and espoused socialism, pacifism, and opposition to American foreign policy during Steinbeck’s lifetime.

Richard Henry Dana, Jr., the author of Two Years Before the Mast, was born 200 years ago in Massachusetts, the home of Dana’s famous Founding family, and of John Steinbeck’s paternal grandparents as well. Growing up, Steinbeck read Dana’s autobiographical account of life along the California coast in the early 19th century–as noted by the artist Tom Killion, the earliest writing, in English, that describes the California coast from the perspective of the sea. New England roots, adventure fiction, California coast: cause enough for Steinbeck fans to celebrate Richard Henry Dana’s bicentennial. But Two Years Before the Mast is also a masterpiece of social-protest literature, like The Grapes of Wrath, and helped set the stage for Steinbeck’s novel. Details of Dana’s life are worth mentioning in 2015, two centuries after his birth and 75 years since the appearance of The Grapes of Wrath. They connect Dana’s era and output with those of Steinbeck—and with the New England artist Rockwell Kent, who wrote popular books of travel, illustrated books by others (including Moby Dick, above), and espoused socialism, pacifism, and opposition to American foreign policy during Steinbeck’s lifetime.

Richard Henry Dana and the Power of Fiction to Change

Born into a Boston Brahmin family of politically progressive lawyers, writers, and legislators, Dana grew up at a time when flogging was routine punishment on ships like the Pilgrim, the California-bound brig he sailed as a merchant seaman after dropping out of Harvard at the age of 19. Like John Steinbeck—who became a college-dropout merchant seaman, briefly, in 1925—young Dana employed fiction as a vehicle to focus public attention on an egregious injustice experienced personally, the brutal mistreatment of sailors at sea. The Grapes of Wrath, written 100 years after Dana drafted Two Years Before the Mast, dramatizes the mistreatment of Dust Bowl migrants through the struggles of a fictional family caught in a Dickensian system of injustice and oppression; Dana’s autobiographical novel describes the pain and suffering of his fellow-sailor Sam, “a human being made in God’s likeness—fastened up and flogged like a beast!” Following the publication of Two Years Before the Mast in 1840—exactly 100 years before Steinbeck’s Sea of Cortez expedition along the Baja, California coast—flogging at sea finally ended, a process Dana helped hasten in his career as a maritime lawyer and legal writer. Though he never wrote another novel, he returned to the California coast in 1859, adding a postscript to later editions of Two Years Before the Mast describing the changes he observed.

Born into a Boston Brahmin family of politically progressive lawyers, writers, and legislators, Dana grew up at a time when flogging was routine punishment on ships like the Pilgrim, the California-bound brig he sailed as a merchant seaman after dropping out of Harvard at the age of 19. Like John Steinbeck—who became a college-dropout merchant seaman, briefly, in 1925—young Dana employed fiction as a vehicle to focus public attention on an egregious injustice experienced personally, the brutal mistreatment of sailors at sea. The Grapes of Wrath, written 100 years after Dana drafted Two Years Before the Mast, dramatizes the mistreatment of Dust Bowl migrants through the struggles of a fictional family caught in a Dickensian system of injustice and oppression; Dana’s autobiographical novel describes the pain and suffering of his fellow-sailor Sam, “a human being made in God’s likeness—fastened up and flogged like a beast!” Following the publication of Two Years Before the Mast in 1840—exactly 100 years before Steinbeck’s Sea of Cortez expedition along the Baja, California coast—flogging at sea finally ended, a process Dana helped hasten in his career as a maritime lawyer and legal writer. Though he never wrote another novel, he returned to the California coast in 1859, adding a postscript to later editions of Two Years Before the Mast describing the changes he observed.

Two Years Before the Mast exposed an evil practice, just as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Julia Ward Howe’s “John Brown’s Body”—the source of Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath” title—excoriated slavery and advocated abolition, the other great cause to which Richard Henry Dana devoted his long life. The Emancipation Proclamation made slavery illegal in the United States in 1863, and Dana served as U.S. counsel at the trial of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, after the Civil War. Ironically, a bloody war fought 75 years later served to integrate poor families like the Joads into the American economy, ending the conditions dramatized in The Grapes of Wrath. Like The Grapes of Wrath, Two Years Before the Mast was written in a turbulent time, and has never been out of print. Dana’s classic, still rewarding reading for Steinbeck fans, is full of resemblances to elements in Steinbeck’s work, including memorable descriptions of the California coast, meditations on social and economic policy, and an Easter Sunday chapter reminiscent of Sea of Cortez.

Dana, Steinbeck, and Rockwell Kent: An American Legacy

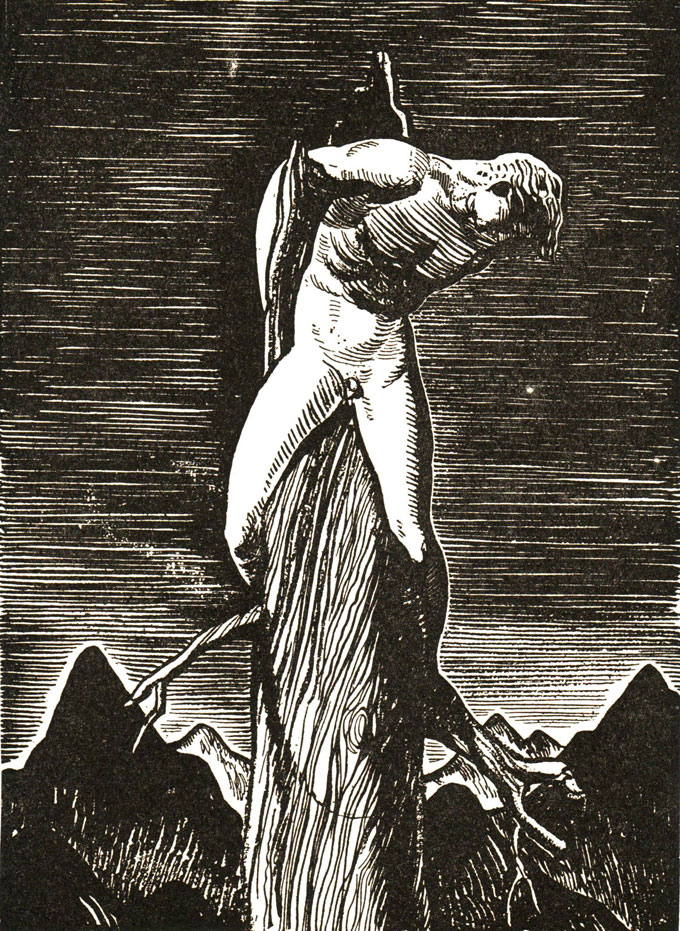

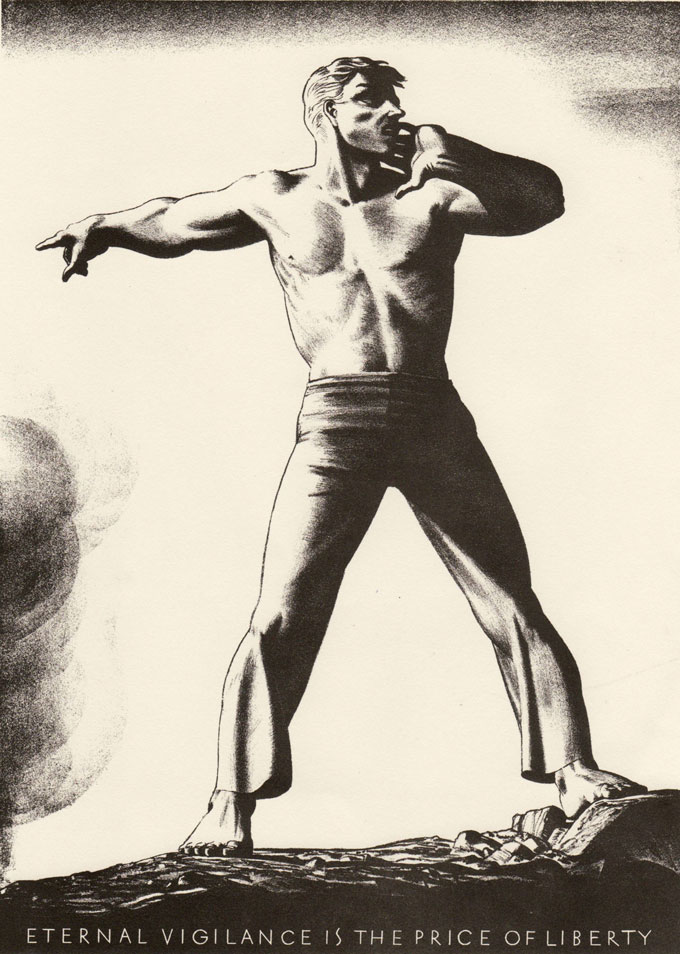

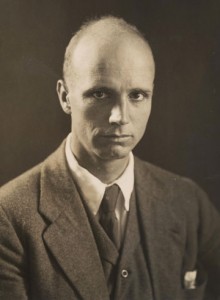

Unlike John Steinbeck, Richard Henry Dana was a polished speaker who advocated progressive policy from a position of social strength and achieved celebrity without being demonized. A closer parallel to Steinbeck in this regard can be found in the life of Rockwell Kent, a gruff adventurer who was born in 1882, the year Dana died, and who managed to outlive Steinbeck by two years. Kent’s writing, autobiographical in source, was realistic. His art was visionary, allegorical, and mythic. His illustrations of works by Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Melville—the American author most influenced by Dana, and an inspiration for Steinbeck—are particularly powerful, so impressive that one wishes he’d been commissioned to illustrate The Grapes of Wrath, a book he read with the recognition of a kindred spirit. Like Steinbeck, Kent rejected conservative politics, revealed religion, and conventional morality. Like Steinbeck, he espoused free living and engaged in social issues with a passion uncharacteristic of his parents and peers. Like Steinbeck, he married repeatedly, traveled relentlessly, and found an appreciative audience in Russia, where he journeyed in 1967 after a fight with the federal government over his passport. In a televised Cold War confrontation, Kent defied Senator Joseph McCarthy, pleading the Fifth Amendment not because he was a communist (he wasn’t), but to show solidarity with American artists and authors blacklisted for being sympathetic to socialism (which he was).

Unlike John Steinbeck, Richard Henry Dana was a polished speaker who advocated progressive policy from a position of social strength and achieved celebrity without being demonized. A closer parallel to Steinbeck in this regard can be found in the life of Rockwell Kent, a gruff adventurer who was born in 1882, the year Dana died, and who managed to outlive Steinbeck by two years. Kent’s writing, autobiographical in source, was realistic. His art was visionary, allegorical, and mythic. His illustrations of works by Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Melville—the American author most influenced by Dana, and an inspiration for Steinbeck—are particularly powerful, so impressive that one wishes he’d been commissioned to illustrate The Grapes of Wrath, a book he read with the recognition of a kindred spirit. Like Steinbeck, Kent rejected conservative politics, revealed religion, and conventional morality. Like Steinbeck, he espoused free living and engaged in social issues with a passion uncharacteristic of his parents and peers. Like Steinbeck, he married repeatedly, traveled relentlessly, and found an appreciative audience in Russia, where he journeyed in 1967 after a fight with the federal government over his passport. In a televised Cold War confrontation, Kent defied Senator Joseph McCarthy, pleading the Fifth Amendment not because he was a communist (he wasn’t), but to show solidarity with American artists and authors blacklisted for being sympathetic to socialism (which he was).

Though Kent failed to produce a magnum opus comparable to The Grapes of Wrath or Two Years Before the Mast, he deserves attention as an artist-activist equal in passion to John Steinbeck and Richard Henry Dana and—based on his courage—even worthier of praise. A biography of Rockwell Kent equal in scope to Jackson Benson’s life of Steinbeck should be written to increase appreciation of Kent’s achievement, preferably from the angle being taken by William Souder in his new book about Steinbeck: “Mad at the World.” Meanwhile, Dana’s bicentennial has produced a splendid biography by former Vermont Supreme Court Chief Justice Jeffrey L. Amestoy, aptly titled Slavish Shore: The Odyssey of Richard Henry Dana Jr. The recent Vermont Public Radio interview with Amestoy about the writing, publication, and impact of Two Years Before the Mast will strike a familiar note with fans of Steinbeck and The Grapes of Wrath. From rural New England to the California coast, the social-protest theme in American literature is an enduring legacy. It began with Richard Henry Dana 200 years ago.

Memories of Eastern Kentucky and the Jersey Shore: Meditations on Loss In Life-Poems by Roy Bentley

Railroad Depot at Fleming, Kentucky: November, 1915

It would have been a gunmetal gray rail line for snakes

to cross but no snake visible. It would have been beautiful,

the cloud-veil of locomotive breath. And starlight-struck.

Behind the depot: laurel thickets. A sign for horse feed.

Denuded limbs would gray the hills, the shadow train

in the right of way speeding alongside an actual train.

There’s horizon, and there’s red-poppy-colored light

on the platform, and a man would have patted a pocket

of his overalls for the fresh tin of Prince Albert tobacco.

I want to hold title to those rich acres in the bottomland

and I want no one to hold title to it but for wildflowers

to grow at the side of a wagon-furrowed road. I want

to watch my dear dead waltz into Paradise, spirit-

heads high, setting aside histories as they commence

stepping off distances to build houses. Towns. Cities.

In 100 years these may talk the pace of human rights

and Snow on the Mountain Fall Blooming Camellia

as a symbol of expectation in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Today, the locomotive is taking on water. Its engineer

slouches. Maybe he smells wood or coal smoke or both.

See other men rising to their full heights. Hear the voices

separate extant pain from the gorgeously swaddled world.

See the white-haired man with the scratched, blue suitcase.

Each of these has felt one recent grief fresh upon waking.

Gloryland Effect

My grandmother Potter said her son Earl died from a gunshot wound.

Said that Johnny Belcher had shot him—Earl—in a bar in Kentucky.

She showed me the 8 x 10 of Earl in army uniform, visor cap cocked

on his head, the cap more than broken in with wear on parade grounds

and on leave after battles, a glow about his handsome long-dead face.

She called that sepia glow the Gloryland Effect. I was falling asleep

the first time she handed me the photograph, and I dreamed of him,

my murdered uncle who read Zane Grey and fathered children

before a single bullet in his liver ended his dreams, if he had any.

I dreamed of him in a place I supposed was heaven or the Afterlife.

In one of those whispers for which the dead in dreams are famous,

he said I should be careful growing up. Said I should love her for him,

my grandmother, his mother with a wide center part in her gray hair.

And I woke with that 8 x 10 vanished into her Samsonite suitcase.

I called her and she came to me, having traveled at the speed of love

after many losses; some great, some less so. She spoke and I knew

each of us has a glowing soul of which we never stop speaking.

Members of the Primitive Baptist Church

Attend a Creek Baptism by Submersion

The line of worshipers collects by an August creek bank.

Their song goes Shall we gather at the river, the beautiful

the beautiful river . . . The creek isn’t much during summer,

though it will all but cover a convert to his or her waist.

A woman in white is holding a man’s fedora. Another

is wading out from the bank into russet-colored water.

Frances Collier Potter is here, hair bobby-pinned up.

In epistolary First Corinthians, the Apostle Paul says

that the hair of any woman is her glory and covering.

Her pastor says it says that. Adds salvation is no joke.

If it is a joke, grace, the punchline is accepting Christ

with the faith of a child: meaning as blindly trusting

as anyone, male or female, gets in Letcher County.

Ask anyone about Letcher County and you’ll hear

that if God plays favorites, this isn’t one of those.

Ask about the Redeemer any time but don’t ask

Frances Collier Potter about a child she lowered

into black as familiar as the slap from a brother

or husband. In the fish-slaughtering coal mine

run-off, closer to an understanding of laurels

than the supernatural, she lets go the memory

of star thistles of frost on glass after the death.

Even if it’s true that good moonshine covers

a multitude of sins, this is the wrong woman

to fuck with. Glory or no glory, she hikes up

her cotton robes and goes in to put one eye

to the task of keyholing the door to mercy.

The Universe as Drunk Girlfriend

Unchecked, she opens an event horizon of a mouth

and out it comes: the turd-in-the-punchbowl analogy

disbursing both the n-word and a sexual metaphor

involving black holes. Occasionally, a side boob

will tease in the way that the God particle does—

dancing a waltz with Mind, a roiling tango. Maybe

the reason that suffering surrounds her has to do

with a mother dropping dead in an airport in Ohio

and then a father running off with a plate-spinner

who performed before The Beatles on Ed Sullivan.

Singularities and space-time rifts were born in her,

though her singular nature comes with firecrackers.

Matches with archangels on the matchbook cover.

Though there are no instructions in any language,

there are some who say the fuse is labeled After

lighting, run. If there is Spirit, hers dances—

with or without a partner and music. Hearts

like hers stagger around backstage at rehearsals

waiting for the next big bang-boom. A beauty,

she is some piece of work. Remember the time

she ran over that dog, then asked you to get out

and see just what sort of damage she had done?

Remember how much you loved her, her mystery

and how, in her wake, it collected as pockets of

absence? Lately, they say she travels with a cat.

A fat tabby she’s named The Strength of Lies.

The animal is reportedly fond of starscapes.

Huckleberry Finn Wanders into Westeros

I was 17 and three days a runaway when I stole Life

on the Mississippi from Becky Thatcher’s Bookstore

on North Main Street in Hannibal, Missouri. The spine

of a Penguin paperback read New American Library.

Outside, it was a blue-sky May afternoon and I was

an hour too late to be admitted to the home of Sam

Clemens’ childhood sweetheart, Laura Hawkins.

All right, 40 years later I’m at Lefty’s Tavern

near the Jersey Shore. Checking voicemails.

And I want to hear above the Game of Thrones-

themed wedding they’re hosting. Third playback,

I hear Results came back negative. No cancer.

And I order a Rebel IPA. Toast the revelers.

If Jorah Mormont is battling greyscale carriers,

stonemen, his best man the dwarf Tyrion Lannister

dodging death by a thousand cuts from paper swords,

it isn’t on the Mississippi. And if Huck and Jim put in

anywhere in Westeros, Jim gets beheaded or lynched,

left to twist as a species of strange, unspecified fruit.

But at Lefty’s Tavern, the news is all good. A bride-

as-Daenerys-Targaryen, cleavaged, three firedrakes

in attendance by a spray of long-stemmed red roses,

is trying to shoplift bliss, the new American variety.

In that story, a queen walks dragon eggs from fire

and a knight-protector is mesmerized forever after,

a runaway slaver risen from the ashes of disgrace.

In make-believe, all ravens are starlight-throated;

in Barnegat, you steal cable and park a Cadillac

on cinderblocks behind Lefty’s. Fantastic is as

fantastic does. If the body is a raft, then those

borne along on it rate at least one dragon egg

above a drone of messages it’s hard to hear.

“October Piece” (1969), the illustrative image evoking John Steinbeck’s California boyhood and Roy Bentley’s memory of a train depot in Kentucky, is a popular print by the critically acclaimed contemporary American artist Peter Milton.—Ed.

True Story: Swimming on Huckleberry Hill in the 1930s

In the days before paved roads or drains or electric power lines, the hill overlooking Monterey, California was home to little more than the roaming deer and several million migrating butterflies, the latter returning each autumn to cluster on the needles of the towering pines. At the base of the trees, wild huckleberry bushes flourished. Robert Louis Stevenson knew the hill from his time when, as an impoverished Scots emigrant, he began writing Treasure Island. In his essay “The Old Capitol,” Stevenson described the 1879 Monterey, California landscape like this:

You follow winding tracks that lead nowhither. You see a deer, a multitude of quail arises. But the sound of the sea still follows you as you advance, like that of wind among the trees, only harsher and stranger to the ear; and when at length you gain the summit, outbreaks on every hand and with freshened vigour that same unending, distant, whispering rumble of the ocean; for now you are on top of Monterey Peninsula, and the noise no longer only mounts to you from behind along the beach towards Santa Cruz, but from your right also, round by Chinatown and Pinos lighthouse, and from down before you to the mouth of the Carmello river. The whole woodland is begirt with thundering surges . . . [and] a great faint sound of breakers follows you high up into the inland canyons . . . go where you will, you have but to pause and listen to hear the voice of the Pacific.

Only 30 years before Stevenson arrived, the Spanish conquistadores had abandoned their fort, the presidio built in the previous century on the hill overlooking the town that served as the center of Spanish and Mexican provincial government in California, until statehood in 1850. Even before California joined the Union, non-Spanish settlers were flocking to the Monterey Peninsula, a place of limitless beauty, abundance, and opportunity. Chinese immigrants who laid America’s railroads came and stayed to fish and raise families. Greek, Portuguese, and Italian fishermen arrived during the Gold Rush, discovering a different gold in the rich shoals of sardines that swarmed in the waters of Monterey Bay. Soon, factories that specialized in packing the fishermen’s catch into tin cans sprang up along the shore, and ever so gradually the quiet Spanish settlement of Monterey, California became an active American community. Like Robert Louis Stevenson, writers and painters were increasingly attracted to its charms, and it became a center of artistic as well as economic activity.

Adventurous souls who worked with charcoal and paint, those who worked with slippery hands shaping clay, others who chiseled marble and wood to make sculptures, they came together on the Peninsula seeking artistic camaraderie. There were writers and poets too, and though young John Steinbeck was not a stranger in the area—having been born in nearby Salinas—he was readily attracted to the bohemian enclave that was forming on the hill above the town. To them, the huckleberries growing beneath the pines made naming it Huckleberry Hill seem natural. Nearby, the side of the hill that looked down on Pacific Grove was, for obvious reasons, called Strawberry Flats, and the overflow of bohemian newcomers began to settle there.

Whether on the Hill or in the Flats, it was everything that Stevenson said it was, and day or night the air was clear and still: it smelled of pine and eucalyptus, and when the wind changed and came off Monterey Bay, the air would become rich with the scent of seaweed and salt. It was from there that the putt-putting sounds of the fishermen’s boats came, the cries of the gulls and the barking of the seal lions that mingled in turn with the whistles and shouts from the row of canneries now standing at the base of the Hill.

After the artists arrived, word spread that parcels of land on either side of the Hill were for sale. And they were cheap. Soon adventurous souls who were finishing their studies at Stanford or Berkeley headed south and bought 25’x60′ building lots for $25 each—though I could be wrong: they may have been 25’x100′, and the price might have been $50. The creative ones came, alone and in pairs, and houses were hastily constructed, many of them from the rough redwood boards that were harvested from the sea after barges full of redwood bound for sawmills in the south floundered in high waves, dumping their loads into the bay, where the lumber became rich pickings for those on shore.

A dozen years later, the roads were covered with asphalt, drains were laid underground, and electricity poles became evident. With natural beauty at every turn, and with near-perfect weather and excellent companionship, all seemed to be going well in that best-of-all-possible-worlds, until the economic situation beyond those pine and eucalyptus groves turned bad in the 1930s and the entire country went into a long depression. The odd jobs and cannery work that helped keep the artists and artisans in bread and wine quickly vanished. However, thanks to progressive measures like the Works Progress Administration (WPA), government-funded employment eventually became available. Artists were hired to paint murals on buildings and inside the post office in Salinas, and writers were given jobs writing recipe books, travel guides, and pamphlets explaining how to can and preserve fruits and vegetables. John Steinbeck did that kind of writing, and his friend Bruce Ariss painted murals.

I mention Bruce Ariss because, as a latecomer to Huckleberry Hill, I lived in the house next to his, and he was the neighbor I knew best. Like many artists in the 1930s, his paintings depicted the lives of the people in the streets, on the farms, and in the factories of Pacific Grove, Salinas, and Monterey, California. A university graduate and champion collegiate boxer, he was a jack of all trades: painting, writing, editing, acting, directing, and more. Also, he was a passionate builder. He’d purchased three lots on the Hill, and he indicated that his plan was to eventually cover every available inch with a single house. The home be built was one of the first on Huckleberry Hill, and as his family grew, so did his house. Created more or less as he went along, it was not a straightforward house. John Steinbeck was to say to him one day, “Yours is an achievement over modern architecture.”

There were any number of potters living on Huckleberry Hill, and on those occasions when their creations met with disaster in the kiln, Bruce was there to collect the broken bits. From them he constructed colorful mosaics. And having an abundance of the shards on hand, he conjured up the idea of putting a soaking-pool in the middle of his front room. He began by digging a circular hole about eight feet in diameter and close to three feet deep, placing it just in front of his large stone fireplace. During the cementing process, he carefully added the potters’ bits and pieces to create a colorful mosaic tub, making sure there were no sharp edges. When it was finished he filled it with water from a garden hose. It tested well. “Never warm, but always invigorating”—that was how Bruce described the pool to me.

One day, Bruce and his “bride”—as he always referred to his wife Jean— were trying out the pool with Carol and John Steinbeck and a couple of other Huckleberry Hill people. Some were in the water and some were stretched out on blankets around it, enjoying the afternoon, when there was a weak knock at the Ariss door. That was very odd, for nobody knocked on the Ariss door: anyone and everyone simply walked in.

“Come in,” someone hollered, and a man entered. He was a small man, a gentle-looking fellow with wire-rim glasses, very properly dressed in a suit and tie. He politely removed his hat. Most of those lounging around the pool immediately recognized him as the overseer of their WPA work in Salinas. He was their boss, and he’d driven his rickety old Ford to Monterey to find out why no one from the Hill had shown up for work that day.

Stepping through the door, the man drew up short noticing that, apart from himself, there wasn’t a single soul in the room with so much as a stitch of clothing on. He looked down at his hat in his hands and began mumbling—something about the work that had to be done in Salinas, about his duty as supervisor, about his just checking to see . . . .

“Well, look, I’m sorry, I didn’t know . . . ah, we’ll talk about that when I see you in Salinas tomorrow,” he said, directing his words at no one in particular and preparing to make a hasty departure.

“We can talk now if you like,” Bruce replied. “I know you’ve had a warm, dusty drive over. You might as well take off what you’re wearing and get in and cool yourself off. And here,” he said, holding up a gallon jug. “There’s plenty of this, help yourself.”

The quiet little man lifted his head, looked around the room at the glistening bodies, then smiled. “Yeah, sure,” he said, and in a flash he was out of his attire, dangling his feet in the water and reaching for the jug of wine.

From the Sierra Madres to The Milky Way: New Poems By Kathleen S. Burgess

He’s So Fine

I hum with a radio tune on a dirt road detour

through the Sierra Madres. Despite swerves

and potholes, most riders sleep. It’s clear

the Chiffons’ doo-lang doo-lang doo-lang

underlies George Harrison’s My Sweet Lord

in the way magma lifted these mountains.

The driver urges the bus around sharp curves

with no guardrails. Stars shine for attention.

George pleads, I really want to see you, lord,

but it takes so long, my lord. And as if on cue,

the headlights flicker. Flicker. Flicker. Fail.

The radio mutes. Suddenly blind the driver

searches, jiggles switches. Runs off the road.

Our hearts pound like pistons. Brakes squeal

their rabbit-voiced panic. We’re lurching

toward the cliff’s crumbling edge. We stop.

Alleluia wings of doors fold as our driver

steps off-stage to a short-lived applause.

Men follow him out looking into the gorge

with flashlights. Laughing afterjokes.

He opens a matchbook, cups the bright halo

of the match, and exhales his thanksgivings.

He lifts the hood, bends to nerves of the bus.

Fiddles and tightens loose wires. Drives on.

Soon a Milky Way of lights sprawls below.

We merge into beetling traffic. Our driver

pounds a door till a man roused from his bed

yields to our hero’s voice, insistent gestures.

We grab our gear to board the new bus. Once

on the road most passengers sleep, but I watch

bright constellations, the spinning stars, and

a meteor flaming as if to disappear the dark.

Recipes from a Colombian Kitchen

In a smoke-darkened kitchen, an Andean guinea pig

wheeking ¡cuy, cuy, cuy, cuy! is named by its cries.

I lift and cradle the highlands rodent, the cuy pup.

Oversized teeth, rapid breathing, inquisitive eyes,

like any third grader entering a new school year.

Wood flames beneath a full, bubbling enamel pot.

Though American experts will say, Never boil coffee,

the coffee cherries grown, roasted black on this finca,

make a brew smooth as cocoa. A kitchen blade carves

a corner off a brick of panela, crude sugar, to sweeten.

For lunch Custodia prepares a stew of potatoes, garlic,

onion, carrots, tomatoes, a flank steak, salt, cumin, and

a bunch of cilantro added to an ever-simmering stock.

She flings peelings into a corner where the cuyes nest

on a swept dirt floor. There’s plenty for all. Custodia

wields a machete with her right hand. In her left,

purple-brown yuca, a cassava tree root. Quick chops

from end to end, and the skin slips off. Potassium

cyanide concentrates in the rind, so she must wash

the creamy flesh, grate, dry, and grind it into flour.

Like onions or coffee, it’s not for cuyes. Housekeeper

Felicia mixes salt, baking powder, panela, egg, anise

flavor, lard into the flour. She kneads the dough and

flattens it with a rolling pin. Cuts apart the rectangles.

Sets them on a cookie sheet. Scores each with a fork.

I make full moons, crescents, diamonds. When I leave,

Felicia reshapes my efforts. Some of the crisp cookies,

the baked panderos, she saves for the household, then

walks to town, dozens nestled in a basket linen-lined.

At the market, her customers take all but the crumbs.

Game

Under a lantern’s hiss of white gas, at a small bar

on a river, the owners challenge Ted and Yukihiro

to gamble on an Inca game we’ve never played,

Sapo. A brass frog, the sapo, tops a console box.

It’s Peruvian tornillo wood overlaid with leather.

A tropical sky flashes veins of fool’s gold and

rumbles all night with fools’ wishes. From seven

meters the players pitch tokens to twirl the brass

spinners, zing into holes, or the wide brass mouth

for a win. The coins channel and collect below

in square pigeonholes numbered with scores.

After a practice round, they start. And Ted’s bet?

Enough for us to live two months. That burning

water, aguardiente, empties into flushed faces.

We get the hustle. Confident they’ll outshine

these tourists, the local hotshots toast to spirits.

Swell with their coming fortune. Ted and Yuki

miss the sapo, the two- and four-sided spinners,

most holes. Mala suerte, a hard mouth grins.

Too bad. Emilio’s moustache curls upward.

Carlos slaps Yuki’s back. Offers a new game,

new chance. Taunts, Doble o nada, gringos.

They begin. I watch for bottles and knives.

Who wins last matters in the fog.

Pacific

Long days, short rides. Ted and I trudged Atacames flats

close to the equator, and just past sundown we topped

the estuary bank. Below, on the beach, silhouettes

erupted: coconut palms, tents, compadres about a fire.

Later, fiddler crabs probed at leftovers. Sally lightfoots,

reddened by a Coleman lantern, skittered into holes—

theirs or their neighbors’. Too dark to put up our tent,

we lay all night in a shack sieving rain onto our heads.

By daylight we raised our pup tent in sand. Stakes bit

and let go, too short to hold. So Brad and Joanna helped,

wrapping the guy ropes around stones. When the poles

toppled anyway, we strung the lines between two trees.

Around us legs and claws, the remains of crab wars,

littered the shore. We climbed eucalyptus-scented hills,

descended to a one-dock fishing port where we lunched

on fresh catch—luscious and round, tasting of lobster,

and tropical fish pulled in by Ecuador’s trawlers who vied,

three miles out in waters our northern nation contested,

with industrial ships that caught, cut, packaged, iced fish,

and threw back. Sharks trailed in water so reddish gray

all hours that local men feared to swim along the coast.

The sea held them all: blue, lemon, nurse, whitenose, bull.

We didn’t know sharks hunted in shallows, not yet.

So we body-surfed to shore. Tumbled, heads down,

feet up, choking and laughing, skinned, crusted in sand.

Most afternoons we walked to a café and store for beer

and Manicho bars. The chocolate was as full of peanuts

as the sky of stars that night when phosphorescent waves

washed around us. Suspended in stars, we whispered

with the Pacific. The slow sea pulse was the rhythm

of our bodies, the rocking of the whole world,

as we floated, disembodied, invisible in umbra.

East of St. Louis: John Steinbeck, Eugene V. Debs, And Celebrating the Labor Movement in Terre Haute

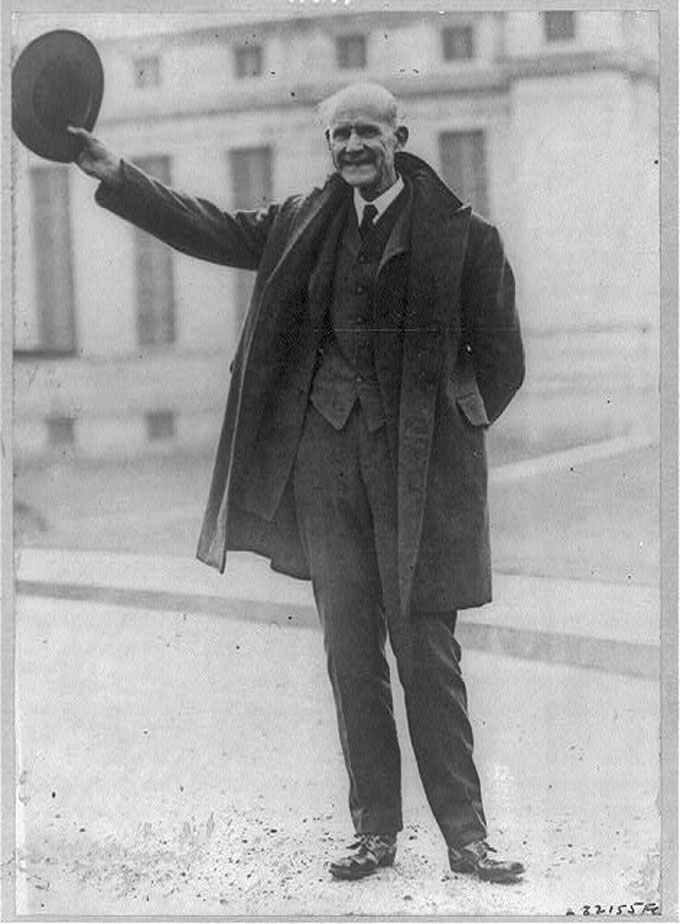

Though Eugene V. Debs is no longer a household name, John Steinbeck’s labor movement novels of the 1930s—In Dubious Battle and The Grapes of Wrath—were influenced by the words and witness of the progressive politician from Terre Haute, Indiana who ran for President in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920. Debs devoted his career to organizing the fight for better wages and working conditions; Steinbeck appropriated his statement of support for the mistreated, malnourished, and marginalized in society—“While there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free”—in the promise Tom Joad makes to his mother in The Grapes of Wrath. Debs uttered his statement in 1918, to the Cleveland, Ohio court that had convicted him of sedition for a speech he gave in Canton, Ohio protesting America’s entry into World War I—a war about which Steinbeck expressed misgivings 25 years later, in East of Eden. Despite repeated defeats during their lifetimes, Debs and Steinbeck remained optimistic about the future of humankind. In his 1962 Nobel acceptance speech, Steinbeck captured Debs’s faith in the possibility—and necessity—of human progress: “I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man, has no dedication nor any membership in literature.”

Eugene V. Debs died in Illinois in 1926, but his memory lives on in the work of the Eugene V. Debs Foundation, located in Terre Haute, Indiana, the city where Debs was born. The not-for-profit organization operates the Eugene V. Debs museum and gives an award each year in Debs’s name to recognize the contributions of outstanding individuals to the cause, much like the John Steinbeck humanitarian award given by the Steinbeck Studies Center in San Jose, California. The 2015 Debs award was made to James Boland, president of the International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers, at a banquet in Terre Haute on October 14. Pete Seeger, the labor movement troubadour honored by the John Steinbeck center in 2009, received the Eugene V. Debs award in 1979.

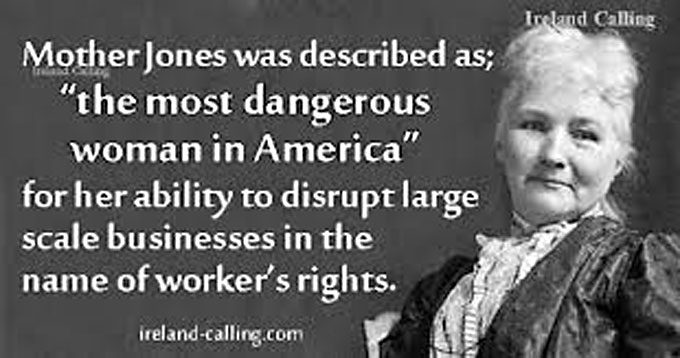

My family and I have been attending Debs award dinners almost that long, and I was pleased to see the Mother Jones Museum represented at this year’s banquet. Mary Harris Jones—a labor movement activist and community organizer in the same era as Eugene V. Debs—was an Irish immigrant, like James Boland and John Steinbeck’s grandparents, Samuel and Eliza Hamilton. Jones was called “the most dangerous woman in America” by critics; like Debs and Steinbeck, she had many, and she was an avid defender of immigrant and worker rights, like Debs and Steinbeck. There is probably no better parallel in modern American literature to the contemporary situation of undocumented workers in the U.S. than Steinbeck’s “Okie” migrants in The Grapes of Wrath. Mother Jones Magazine, a progressive publication, is headquartered in San Francisco, the center of the California labor movement in Steinbeck’s time and the backdrop for Steinbeck’s strike novel, In Dubious Battle.

Since the year the Debs award was given to Pete Seeger, almost every Debs dinner has featured a musician of note on the program. This year’s singer was Dana Lyons, a folk and alternative rock musician from Bellingham, Washington. Many of Dana’s songs concern the environment, but he is most famous for “Cows with Guns,” a hilarious song about another serious subject. John Steinbeck would have appreciated Dana’s sense of humor, as well as the environmental message delivered in the beautiful new music video, “The Great Salish Sea,” which can be viewed at Dana’s website. It sounds the alarm about the effects ship noise and fossil fuels have on the whales of the Salish Sea region in Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia—a region John Steinbeck and his friend Ed Ricketts, early ecologists, knew well.

Another Debs dinner tradition is to have the annual award presented by a prominent proponent of progressive politics. This year’s presentation speaker was Keith Mestrich, president and CEO of Amalgamated Bank, the union-owned bank where Occupy Wall Street kept its funds. Founded in 1923 by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, the bank practices what Eugene V. Debs preached. Recently it raised the minimum wage it pays its employees to $15 an hour, and it is currently funding an ad campaign on New York subways supporting “ The Fight for $15.” When metro officials pulled the bank’s posters from subway cars because the message was too political, Amalgamated ran an ad on the front cover of the free subway paper, and Amalgamated volunteers began collecting signatures for the #RaiseTheWage petition the bank plans to send Congress.

In his remarks, Jim Boland (shown here speaking on TV) cited the influence of progressive writers on his political education, recalling how he felt as a young Irish immigrant to the United States to learn about Eugene V. Debs, the man he called “the ultimate American socialist.” Boland’s father and grandfather were union railroad workers, like Debs and my Irish grandfather, a political activist and socialist. During his speech, Jim cited two writers—John Dos Passos, John Steinbeck’s American contemporary, and James Connolly, the Irish socialist and patriot who was wounded in the 1916 Easter Uprising, then executed for his role in the Irish revolt against British rule. Before returning to Ireland from the United States in 1910 to fight for Irish independence, Connolly was a member of the International Workers of the World (IWW), the union that Debs helped found and that Steinbeck wrote about in the 1930s.

Unlike James Connolly and Eugene V. Debs, John Steinbeck was never jailed because of his politics. But people do die for their convictions in his novels—Casy in The Grapes of Wrath; the young strike organizer, also named Jim, in Steinbeck’s labor movement novel In Dubious Battle. Unlike Steinbeck, Debs is rarely mentioned in American classrooms today. In fact, the contribution of the entire labor movement to the making of American society is barely touched on in most high school history classes. The corporate media treat labor unions and leaders with suspicion, and politicians love to campaign against both, even in states like Indiana with strong labor movement roots. In Terre Haute, the Eugene V. Debs Foundation is working to counter this negative trend. Visitors are welcome at the Eugene V. Debs Museum, which is located on the campus of Indiana State University in Terre Haute. Tips on traveling to Terre Haute and visiting the museum are available on my travel blog.

“The Valley of the World”: John Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley in Color Photography Inspired by East of Eden

More than 60 years after it became a national bestseller, John Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden remains one of the writer’s most widely read works of fiction. Set in California’s Salinas Valley, where the author grew up and is buried, East of Eden recreates a turbulent era in American life, the period from the Civil War to World War I, through two generations of a pair of Salinas Valley families whose individual lives intersect dramatically during an era characterized by change and conflict in the Salinas Valley and on the world stage. In describing the novel’s setting as “the valley of the world,” John Steinbeck clearly meant East of Eden to be read as allegory, like the Old Testament story mirrored in its title, and as autobiography—intended, he said, for his two young sons, growing up far from the Salinas Valley after World War II. In 2010, the Steinbeck scholar Michael J. Meyer asked David A. Laws, a gifted photographer known for his bright images of John Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley, to take a series of photos to illustrate a book of literary essays on East of Eden. Meyer died in 2011, but the process of collecting and editing essays by various scholars of John Steinbeck was picked up and completed by Henry Veggian, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The result was East of Eden: New and Recent Essays, published by Editions Rodopi (now Brill) in 2013 and reviewed here.—Ed.

Images of the Salinas Valley Inspired by East of Eden

My contribution to East of Eden: New and Recent Essays appeared as a black-and-white photo essay—“Literary Landmarks of East of Eden”—comprised of 15 images that I look of locations around the Salinas Valley inspired by passages from John Steinbeck’s epic novel. The text I wrote remains the copyright of Rodopi, but I retained ownership of the following images, published here for the first time from my original color files. Although much has changed since John Steinbeck returned to his hometown in the early 1950s to recall the “sights and sounds, smells and colors” of the Salinas Valley that fill East of Eden, and even more since Adam Trask arrived in search of his own Eden, these images are recent examples of the scenes and settings that informed the author and that continue to convey the essence of those times. Page references quoting the novel are from the edition of East of Eden published by Penguin Books in 2002, John Steinbeck’s centennial.—David A. Laws

“I would like to write the story of this whole valley, of all the little towns and all the farms and ranches in the wilder hills.”—Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten (Penguin Books, 1976), p. 73

“The river mouth at Moss Landing was centuries ago the entrance to this long inland water.”—East of Eden, p. 4

“Then the hard, dry Spaniards came exploring through, greedy and realistic. . . . Of course they were religious people, and the men who could read and write, who kept the records and drew the maps, were the tough untiring priests who traveled with the soldiers.”—East of Eden, p. 6

“There were no springs, and the crust of topsoil was so thin that the flinty bones stuck through. Even the sagebrush struggled to exist, and the oaks were dwarfed from lack of moisture.”—East of Eden, p. 9

The Plaza Hall in San Juan Bautista played the role of the King City hotel in the 1981 “East of Eden” TV mini-series.

“One morning she complained of feeling ill and stayed in her room in the King City hotel while Adam drove into the country. He returned about five in the afternoon to find her nearly dead from loss of blood.”—East of Eden, p. 133

“Later Samuel and Adam walked down the oak-shadowed road to the entrance to the draw where they could look out at the Salinas Valley.”—East of Eden, p. 293

“They left the valley road and drove into the worn and rutted hills over a set of wheel tracks gullied by the winter rains. The horses strained into their collars and the buckboard rocked and swayed. The year had not been kind to the hills, and already in June they were dry.”—East of Eden, p. 137

“’This will be a valley of great richness one day. It could feed the world, and maybe it will.’”—East of Eden, p. 145

“In the country the repository of art and science was the school, and the schoolteacher shielded and carried the torch of learning and of beauty. The schoolhouse was the meeting place for music, for debate. The polls were set in the schoolhouse for elections. Social life, whether it was the crowning of a May queen, the eulogy to a dead president, or an all-night dance, could be held nowhere else.”—East of Eden, p. 146

“’I don’t know whether you noticed, but a little farther up the valley they’re planting windbreaks of gum trees. Eucalyptus—comes from Australia. They say the gums grow ten feet a year.’”—East of Eden, p. 164

“At eight-thirty on a Wednesday morning Kate walked up Main Street, climbed the stairs of the Monterey County Bank Building, and walked along the corridor until she found the door which said, ‘Dr. Wilde—Office Hours 11-2.’”—East of Eden, pp. 240-241

“The traditional dark cypresses wept around the edge of the cemetery, and white violets ran wild in the pathways. . . . The cold wind blew over the tombstones and cried in the cypresses.”—East of Eden, p. 309

“The ‘dobe house had entered its second decay. The great sala all along the front was half plastered, the line of white halfway around and then stopping, just as the workmen had left it ten years before. . . . A smell of mildew and of wet paper was in the air.”—East of Eden, pp. 342-343

“When Adam left Kate’s place he had over two hours to wait for the train back to King City. On an impulse he turned off Main Street and walked up Central Avenue to number 130, the high white house of Ernest Steinbeck. It was an immaculate and friendly house, grand enough but not pretentious, and it sat inside its white fence, surrounded by its clipped lawn, and roses and catoneasters lapped against its white walls.”—East of Eden, p. 382

“It’s a pleasant little stream that gurgles through the Alisal against the Gabilan Mountains on the east of the Salinas Valley. The water bumbles over round stones and washes the polished roots of the trees that hold it in.”—East of Eden, p. 589