Archives for December 2013

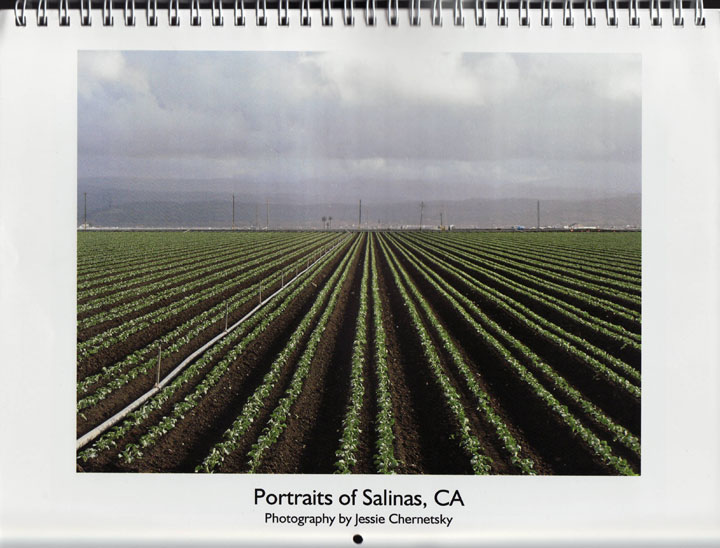

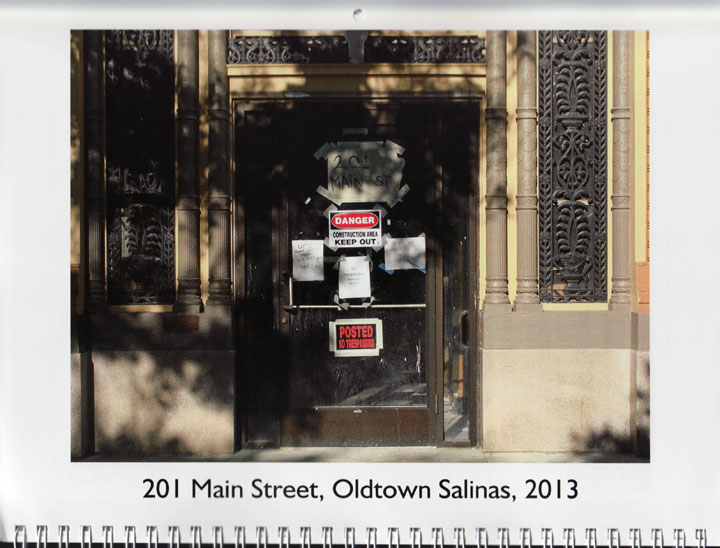

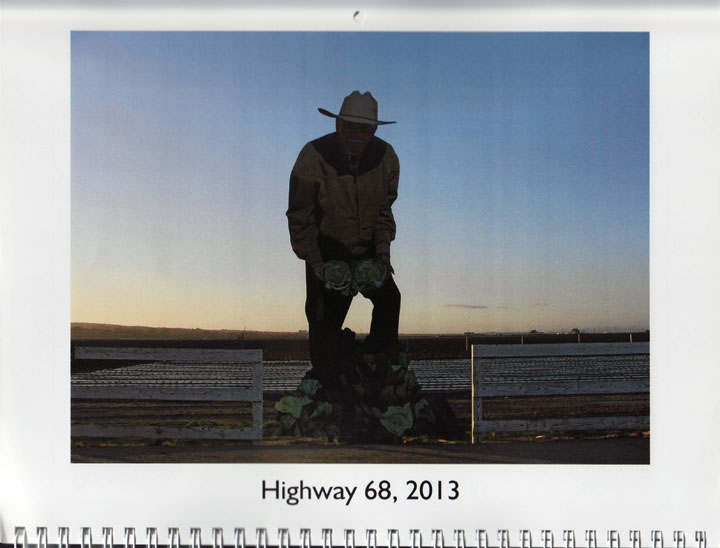

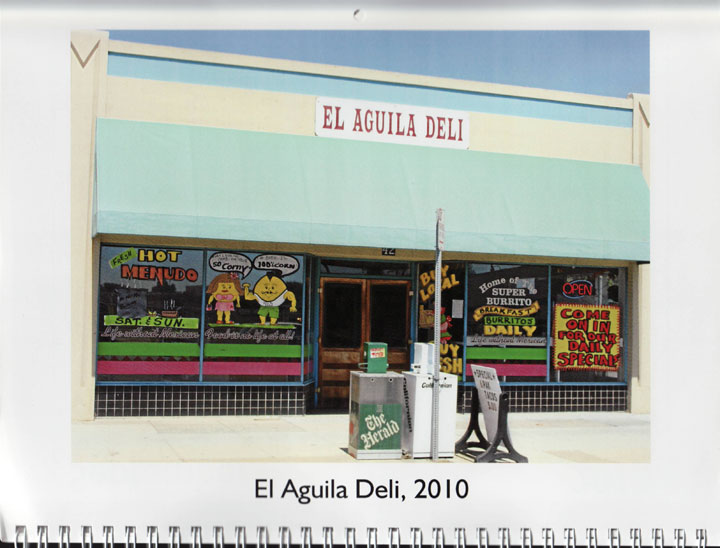

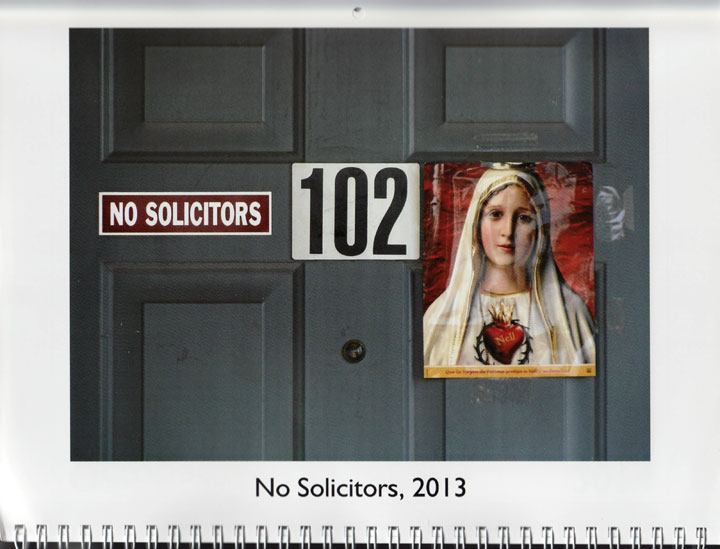

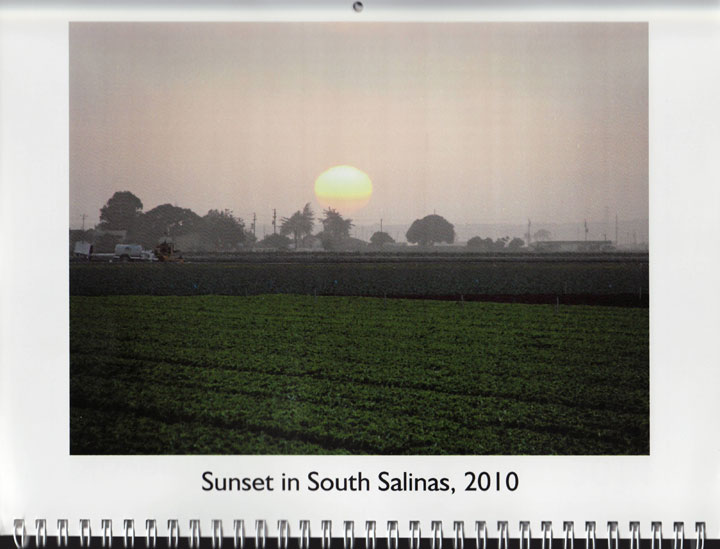

Portraits of Salinas, CA

Still More to Doubt than Do in John Steinbeck’s Salinas

Salinas on Highway 101 in Monterey County is a piece of prose, an almost-odor, an unheard sound, a shade of gray, a pause, a reaction, an amnesia, dreaming of someplace else. Salinas is the have’s and have not’s, wood and brick and river and filled-in slough, cracked pavement and seedy lots and cemeteries, concrete buildings and rotting houses, churches, taco shops, and homeless shelters, and big empty box stores, and doctors’ offices and lawyers. Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, “Rotarians, Republicans, growers and shopkeepers,” by which he meant Somebodies. When the man looked through another peephole he said, “Sinners and vigilantes and racists and hypocrites,” and meant the same thing.

Salinas on Highway 101 in Monterey County is a piece of prose, an almost-odor, an unheard sound, a shade of gray, a pause, a reaction, an amnesia, dreaming of someplace else. Salinas is the have’s and have not’s, wood and brick and river and filled-in slough, cracked pavement and seedy lots and cemeteries, concrete buildings and rotting houses, churches, taco shops, and homeless shelters, and big empty box stores, and doctors’ offices and lawyers. Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, “Rotarians, Republicans, growers and shopkeepers,” by which he meant Somebodies. When the man looked through another peephole he said, “Sinners and vigilantes and racists and hypocrites,” and meant the same thing.

Salinas from Highway 101 Before Reading John Steinbeck

The August afternoon was hot and sticky when I took the Salinas exit from Highway 101 with my oldest college friend, an economics professor and Episcopal priest and gourmet cook from New York visiting Los Gatos, my new home 60 miles north of Salinas. I was a recent Florida transplant, and it was my first trip south on Highway 101 to Steinbeck Country. We knew Steinbeck was born in Salinas, but we weren’t looking for Steinbeck’s ghost. We weren’t even interested in Salinas. We were searching for the perfect artichoke, and the pilgrimage to Castroville and Watsonville—the heart of Salinas Valley’s artichoke industry—takes you through Salinas if you follow Highway 101, the safest route for the uninitiated.

I didn’t know it then, but later I would make the Highway 101 trek south to Salinas every Sunday to play the historic Aeolian-Skinner organ at John Steinbeck’s childhood Episcopal church. Retired from my day job in Silicon Valley and immersed in John Steinbeck’s writing, I decided to discover something new about John Steinbeck’s life in Salinas whenever I was in town. After researching church and town records of John Steinbeck’s upbringing, visiting his home and burial place, and interviewing Salinas residents about their town’s most famous son, I’ve learned a lot and formed an opinion. John Steinbeck was right: there wasn’t much to do in Salinas when he was growing up, and that hasn’t changed. But there is a great deal to doubt in Salinas about the legend of John Steinbeck perpetuated by local interests.

John Steinbeck’s View: Always Something to Do in Salinas

“Salinas was never a pretty town. It took a darkness from the swamps. The high gray fog hung over it and the ceaseless wind blew up the valley, cold and with a kind of desolate monotony. The mountains on both sides of the valley were beautiful, but Salinas was not and we knew it. Perhaps that is why a kind of violent assertiveness, an energy like the compensation for sin grew up in the town. The town motto, given by a reporter ahead of his time, was: ‘Salinas is.’ I don’t know what that means, but there is no doubt of its compelling tone.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

John Steinbeck pondered the Salinas paradox wickedly in “Always Something to Do in Salinas,” a travel piece he wrote for Holiday magazine in 1955. By then Steinbeck had been a non-citizen of Salinas for 35 years—first as a college student at Stanford, later as a struggling writer in nearby Pacific Grove, finally as an international celebrity with homes in Manhattan and Long Island and instant recognition wherever he traveled. But John Steinbeck never forgot Salinas. And Salinas, I found, never forgot or forgave John Steinbeck for what he wrote about the town.

I learned for myself that, as Steinbeck joked, Salinas just is. But the Salinas that is isn’t the town I thought I was seeing when Allen and I passed through on our Highway 101 artichoke pilgrimage seven years ago. Normal Salinas weather is, as Steinbeck noted, not sunny, but high gray fog. Even in summer the gloom is damp and dark, enveloping Salinas like a shroud delivered from the angry sea. Robert Louis Stevenson, the first literary tourist who recorded what Salinas was before John Steinbeck described what Salinas is, compared the newly named Salinas City unfavorably with coastal Monterey, a Catholic enclave with European roots and old world ways. Stevenson, the son of a Scottish Presbyterian engineer, described Salinas City as an isolated Protestant village dredged from the Salinas River wetlands by sharp-elbowed Yankees, ex-Confederate Southerners, and ambitious immigrants who connived to make upstart Salinas—not established Monterey—the new county seat. Government and agriculture are still the main business of Salinas. Tourists still favor Monterey.

Highway 101: Escape Route from Salinas to High Culture

“People wanted wealth and got it and sat on it and it seemed to me that when they had it, and had bought the best automobile and had taken the hated but necessary trip to Europe, they were disappointed and sad that it was over. There was nothing left but to make more money. Theater came to Monterey and even opera. Writers and painters and poets rioted in Carmel, but no of these things came to Salinas. For pure culture we had Chautauqua in the summer—William Jennings Bryan, Billy Sunday, The World of Art, with slides in a big tent with wooden benches. Everyone bought tickets for the whole course, but Billy Sunday in boxing gloves fighting the devil in the squared ring was easily the most popular.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

According to the Salinas historian Robert Johnson, Salinas had 3,300 residents when John Steinbeck was born in 1902 at his parents’ home on upscale Central Avenue. Despite its modest size, Johnson says that Salinas boasted six or seven churches when the town was officially incorporated in 1874. The most prestigious house of worship in Salinas was always St. Paul’s, the Episcopal church chosen by John Steinbeck’s ambitious mother Olive when the family moved to town in 1900 or 1901. But the high-grade culture John Steinbeck said Olive craved for her children was in San Francisco, a serious schlep by horse, train, or Model-T before Highway 101 finally reached Salinas. San Francisco, not Salinas, was The City for young John Steinbeck, as it continues to be for high-minded Californians like Olive today.

Not that the Salinas churches didn’t have culture of a sort in Steinbeck’s time. St. Paul’s in particular was a social center for the Salinas upper crust, with Sunday services featuring organ music, choirs, soloists, and a string orchestra for special occasions. Local land money built an opera house, and a grant from Andrew Carnegie helped pay for a public library. Parks, pleasure gardens, and cemeteries abounded in and around Salinas for citizens in good standing. But the fading names I deciphered on the crumbling headstones at the Garden of Memories are defintely “whites-only,” and the handful of Japanese and Filipinos who managed to buy land kept to themselves. John Steinbeck’s description of the evangelist Billy Sunday boxing with the devil at a Salinas Chautauqua event suggests that Protestant frontier spectacle, like Salinas society, was viewed through the rose-colored glasses of race-and-class certitude.

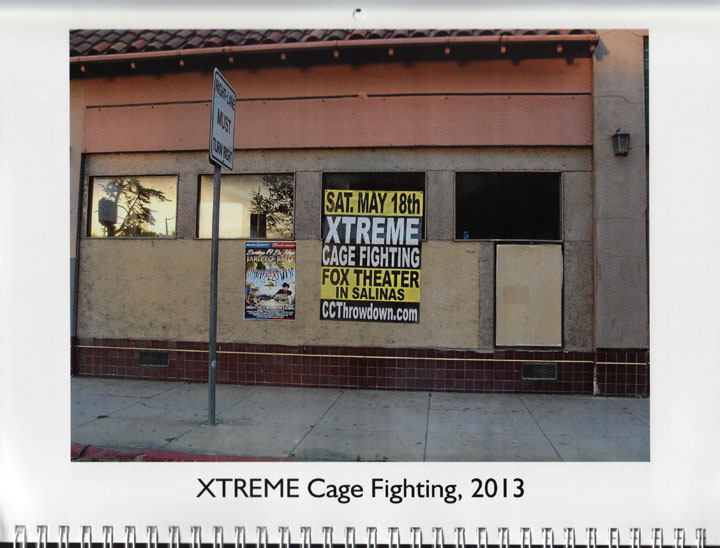

Artists and writers of the period colonized Carmel, not Salinas. They included literary socialists like Jack London and Lincoln Steffens and poets as divergent in style and stature as George Sterling and Robinson Jeffers. The Pacific Grove-Carmel-Monterey cultural axis, not Salinas, was John Steinbeck’s future, and he didn’t fight the call. Like St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in East of Eden, Salinas was a place sensitive souls like John Steinbeck and his character Aron Trask fled from, not to. Years later, when Steinbeck was too important to ignore, a faction in Salinas tried to name a road in his honor. Steinbeck insisted on a bowling alley instead. He won the battle but lost the war. The public library in Salinas is now the John Steinbeck Library. The massive museum on Main Street is the National Steinbeck Center. A dozen businesses with no connection to members of John Steinbeck’s family—all of whom departed Salinas by death or by choice—dot lower Main Street and the strip malls between downtown Salinas and Highway 101. The St. Paul’s parsonage described in East of Eden is now a law office. The church where Steinbeck played, prayed, and acted out in as a boy was torn down for a parking lot, usually empty.

Steinbeck-Denial and the Name-Game in Salinas Today

“We had excitements in Salinas besides revivals and circuses, and now and then a murder. And we must have had despair, too, as when a lonely man who lived in a tiny house on Castroville Street put both barrels of a shotgun in his mouth and pulled the trigger with his toes. That morning Andy was the first in the schoolyard, but when he arrived he had the most exciting article any Salinas kid had ever possessed. He had it in one of those little striped bags candy came in. He put it on the teacher’s desk as a present. That’s how much he loved her.

“I remember how she opened the bag and shook out on her desk a human ear, but I don’t remember what happened thereafter. I have a memory block perhaps produced by violence. The teacher seemed to have an aversion for Andy after that and it broke his heart. He had given her the only ear he or any other kid was ever likely to possess.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

John Steinbeck’s ashes reside not far from the new St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, occupied the same year Steinbeck satirized Salinas for Holiday. The Garden of Memories cemetery was unlocked and unattended the Sunday I visited, and the John Steinbeck plaque was hard to miss. Visible by virtue of inappropriateness, a tacky sign extends a painted finger to the clutter of weeds, wilted flowers, and cracked pavement leading to the Hamilton family plot where John Steinbeck rests. Nearby, an incongruous military tank rests on its concrete laurels next to the Garden of Memories mausoleum, a paradox on a pedestal making a statement I don’t understand and doubt Steinbeck would approve if I did.

John Steinbeck hated war. Salinas appears to hold a more benign view. The historical society grounds in North Salinas feature a display of oddly obsolete and out-of-place military hardware, public anti-art unique in my California experience. The John Steinbeck museum on Main Street shares space with a pocket park honoring local veterans of the Bataan Death March. Is this another Salinas-persona paradox, or a problem best kept to myself? On the right, the Republican, Rotarian Salinians, destested by John Steinbeck, who stayed and prospered in war and peace. On the left, John Steinbeck: New Deal Democrat, Cold War critic, prophet without honor in Salinas until he died. What middle ground could ever marry such opposites? Perhaps that’s why Steinbeck abandoned his Salinas relationship: irreconcilable differences until death do us part.

The Salinians I asked about my problem avoided politics and talked about personalities. The identity of Salinas citizens Steinbeck is thought to have portrayed in his books is the preferred topic of conversation. Opinions are definite but don’t always agree. An ex-parishioner of St. Paul’s expressed her confidence that Steinbeck patterned his character Andy—the Salinas boy who taunts the Chinaman in Cannery Row—on her grandfather, a church and school contemporary of Steinbeck who stayed in Salinas and lived to a ripe old age. A local expert on Salinas history is equally certain this isn’t so. An informed source in Pacific Grove who interviewed the person in question maintains an open mind on the subject.

John Steinbeck’s Salinas: The Forgotten Violence of 1936

“The General took a suite in the Geoffrey House, installed direct telephone lines to various stations, even had one group of telephones the were not connected to anything. He set armed guards over his suite and he put Salinas in a state of siege. He organized Vigilantes. Service-station operators, owners of small stores, clerks, bank tellers got out sporting rifles, shotguns, all the hundreds of weapons owned by small-town Americans who in the West at least, I guess, are the most heavily armed people in the world. I remember counting up and found that I had twelve firearms of various calibers and I was not one of the best equipped. In addition to the riflemen, squads drilled in the streets with baseball bats. Everyone was having a good time. Stores were closed and to move about town was to be challenged every block or so by viciously weaponed people one had gone to school with. . . .

“Down at the lettuce sheds, the pickets began to get apprehensive. . . .

“Then a particularly vigilant citizen made a frightening discovery and became a hero. He found that on one road leading into Salinas, red flags had been set up at intervals. It was no more than the General had anticipated. This was undoubtedly the route along which the Longshoremen were going to march. The General wired the governor to stand by to issue orders to the National Guard, but being a foxy politician himself, he had all of the red flags publicly burned on Main Street.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

The epic suffering of the Joads in California enraged the state and alarmed the nation, as John Steinbeck intended when he wrote his masterpiece. But before sitting down to write The Grapes of Wrath in 1938, he composed an unpublished piece about Salinas he called L’Affaire Lettuceburg, a bitter indictment of the violence with which Salinas responded to the 1936 strike by produce packers from the Alisal, an area east of Highway 101 called Little Oklahoma. Warned by his wife Carol that he was writing too close to home and far beneath his capacity as an author, Steinbeck started over again, shifting his vision from Salinas to California’s Central Valley and completing The Grapes of Wrath 60 miles north of Salinas in Los Gatos. But he neither forgot nor forgave what happened in Salinas in 1936, returning to the episode in his piece for Holiday and holding it in his heart, according to his letters, with a indelible mortar of anger and pain. Yet no one living in Salinas today, or with parents living in Salinas at the time, was willing to talk with me about Salinas under martial law 80 years ago.

The burning of The Grapes of Wrath in Salinas in 1939 (and maybe in 1940 as well) is another story. Period photos and first-hand accounts are pretty convincing, and most Salinians I spoke with acknowledge their credibility. A recent book about the extreme reaction to The Grapes of Wrath throughout America both dates and locates the 1939 burning of the book in Salinas. I learned about the later burning from a taped interview with the late Dennis Murphy, the son of John Steinbeck’s church and school mate John Murphy and the author of The Sergeant, an under-appreciated novel that Dennis Murphy completed with John Steinbeck’s encouragement and scripted into a 1968 movie starring Rod Steiger. But this evidence failed to dissuade Salinas enthusiasts who are engaged in an effort disprove that The Grapes of Wrath was ever burned publicly in Salinas.

Highway 101: Today’s Salinas Exit, Yesterday’s Social Wall

“All might have gone well if at about this time the Highway Commission had not complained that someone was stealing the survey markers for widening a highway, if a San Francisco newspaper had not investigated and found that the Longshoremen were working the docks as usual and if the Salinas housewives had not got on their high horse about not being able to buy groceries. The citizens reluctantly put away their guns, the owners granted a small pay raise and the General left town. I have always wondered what happened to him. He had qualities of genius. It was a long time before Salinians cared to discuss the episode. And now it is comfortably forgotten. Salinas is a very interesting town.”

—John Steinbeck, “Always Something to Do in Salinas”

According to Robert Johnston’s history, following World War II Salinas city leaders tried to mend fences with the Okies east of Highway 101 in a top-down electoral campaign to incorporate the Alisal into Salinas. But the files of the period I found at St. Paul’s make me doubt the Salinas fathers’ motives as much as their methods. Richard Coombs, the young rector recruited from New York to build a new church for St. Paul’s, reminded his parishioners that they had sinned and fallen short by failing to extend the church’s ministry to the people of the Alisal when help was needed. By the time Coombs arrived in Salinas, the Episcopal bishop in San Francisco had mandated an Episcopal mission east of Highway 101 to fill the gap. Another mission was started in North Salinas, and a third was later established in Corral de Tierra, the setting of Steinbeck’s Pastures of Heaven. It’s called Good Shepherd; Steinbeck’s heavenly pasture is an upscale enclave of luxury homes, horse ranches, and golf-and-tennis clubs—precisely the future Steinbeck predicted for Corral de Tierra in 1932.

Incidentally, I was invited to speak recently to a Rotary meeting at a Corral de Tierra tennis club where a celebrity tournament was underway, a media circus that required the Rotary meeting to move to the club bar. I felt at home I suppose, but I could have been in Aspen or Boca Raton, other pastures where I’ve also enjoyed bar life among the affluent. This week I was back in Salinas to play for the Christmas Eve service at St. Paul’s. Arriving later than expected because of heavy Highway 101 traffic, I looked for a quick place to eat before the choir rehearsed at 8 p.m. Pulling into a tony restaurant near St. Paul’s, a favorite of the Sunday church crowd, I watched the Open sign in the window fade to black as lubricated patrons pushed past my car on their way to the parking lot. A straggler, a Salinas matron with a voice like a chain saw, clipped my bumper with her handbag. “Jesus!” she screamed, pounding my trunk. “You’re moving too fast. Now I think I’ll just a move little slower so you’ll be even later to wherever the hell you think you’re going!”

Mouthing a Merry Christmas, I turned toward the fast food place advertising Open Till 8 across the street. Inside, the young lady who took my sandwich order smiled and apologized for having to close early for Christmas, explaining that this was her first fast-food job and she knew people would still be hungry. I tipped her $10 for my five-dollar meal, and this time I meant it when I wished her Merry Christmas. I felt better about Salinas because of her, and I hope she finds something to do in Salinas and stays in John Steinbeck’s home town. But I have my doubts. And I’ve made my last late-night drive to foggy Salinas. Playing the organ at St. Paul’s has been wonderful and I’ll miss everyone. But I’ve gotten the best gift an outsider like me can expect from Salinas: John Steinbeck. No doubt at all about that. And John Steinbeck travels well.

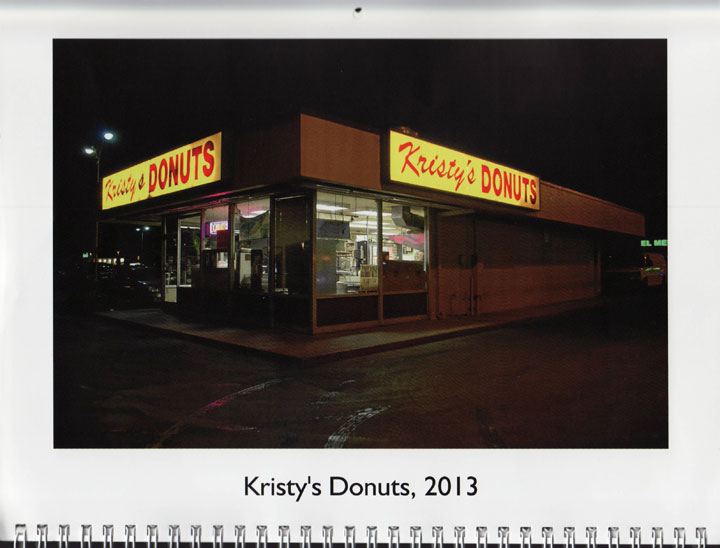

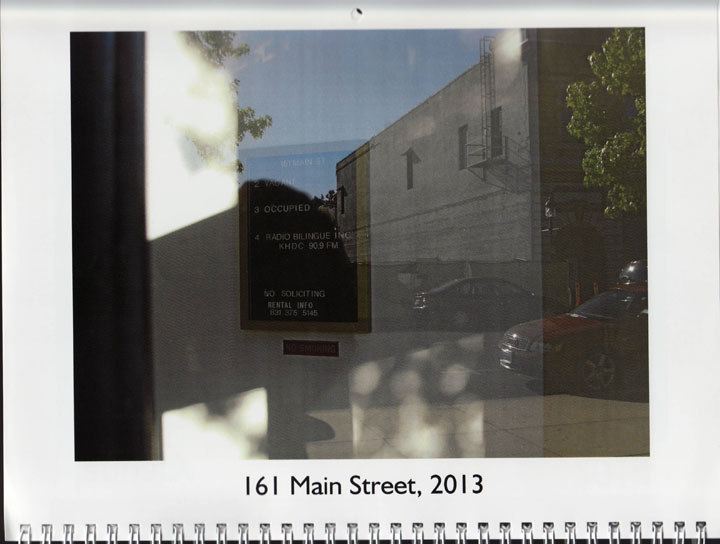

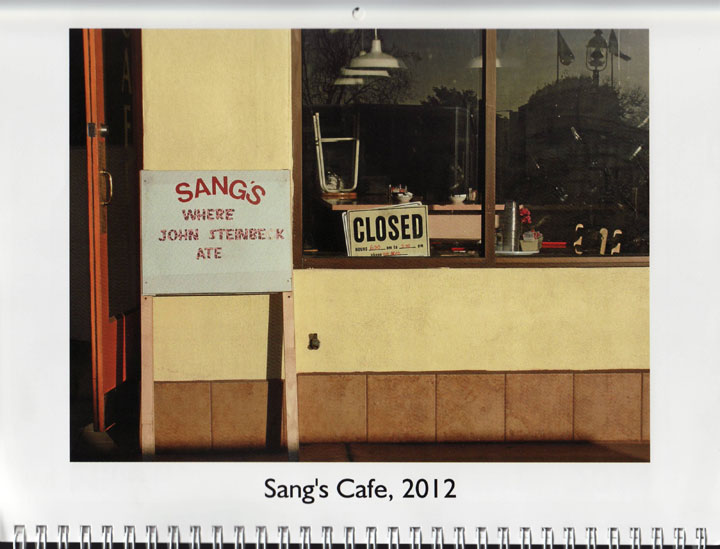

“Sang’s Cafe” in Salinas, photograph by Jessie Chernetsky courtesy of the artist.

John Steinbeck Inspires Monterey County Visual Arts Masters, Past and Present

The rugged coast and majestic mountains of Monterey County, California, inspired awe-struck visual arts professionals and amateurs long before John Steinbeck appeared on the scene. So it seems natural that Steinbeck, born and raised in Monterey County, was attracted to the visual arts and met well-known artists of the period, such as E. Charlton Fortune and Armin Hansen, California Impressionist painters who lived and created much of their most popular work in Monterey County.

The rugged coast and majestic mountains of Monterey County, California, inspired awe-struck visual arts professionals and amateurs long before John Steinbeck appeared on the scene. So it seems natural that Steinbeck, born and raised in Monterey County, was attracted to the visual arts and met well-known artists of the period, such as E. Charlton Fortune and Armin Hansen, California Impressionist painters who lived and created much of their most popular work in Monterey County.

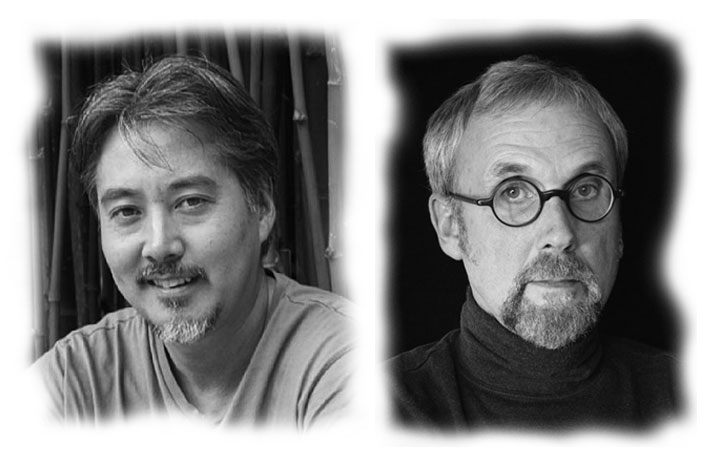

Writing in and about Monterey County in the 1930s and 40s, Steinbeck befriended a host of younger artists who were, like the author, perfecting their craft in the company of colleagues, friends, and lovers. But the ripening John Steinbeck-Monterey County-visual arts connection didn’t end with the author’s death. Forty-five years later it continues in the work of contemporary Monterey County painters including Warren Chang (above left) and David Ligare (above right), successful artists who differ in technique but share a source of inspiration in the literary landscapes of John Steinbeck.

John Steinbeck and the Visual Arts in Monterey County

Steve Hauk—the Monterey County writer and art dealer who co-curated This Side of Eden – Images of Steinbeck’s California, the inaugural exhibition of the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas—is an expert on John Steinbeck and the visual arts, past and present, in Monterey County. He was interviewed for films on E. Charlton Fortune and on John Steinbeck and his Monterey County artist circle for the 100-Story Project, an archival narrative of Monterey County history and culture. Among the best known members of Steinbeck’s circle were several artists—notably James Fitzgerald, Ellwood Graham, Judith Deim, and Bruce Ariss—who created notable portraits of the author, a shy person who enjoyed being painted but didn’t like to be photographed.

John Steinbeck also befriended artists beyond Monterey County. Among his closest confidantes was Bo Beskow, the Swedish painter who completed portraits of the author at Steinbeck’s request in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. The American painter Thomas Hart Benton, whose perspective on his native Midwest mirrored Steinbeck’s passion for Monterey County, never met the writer but shared his populist politics and anti-elitist aesthetics. Benton’s illustrations for a special edition of The Grapes of Wrath captured the book’s spirit so well that the writer and the artist became synonyms for sentimentality among critics of their work.

Today the Canadian painter Ron Clavier continues the John Steinbeck-visual arts tradition beyond Monterey County in paintings that portray passages from The Grapes of Wrath. A neuropsychologist by training, Clavier unites science and the visual arts in painting that would have appealed strongly to Steinbeck’s sense of unity, universality, and nature. “As a visual artist,” says Clavier, “I dream that I might replicate the magnificent imagery of the world, and by doing so, remind others of their own core decency,” adding that “each day, I try to experience what American author and Nobel Laureate John Steinbeck described as awe, humility, and joy.”

The Visual Arts in Action: Warren Chang and David Ligare

David Ligare and Warren Chang are leading examples of contemporary Monterey County artists whose work reflects Steinbeck’s empathy for the dispossessed and the author’s love of the Monterey County landscape. River/Mountain/Sea—Ligare’s current exhibition at the Monterey Museum of Art—is a compelling example of the John Steinbeck-Monterey County-visual arts phenomenon that has made Monterey County a mecca for aficionados of the visual arts and Steinbeck fans alike. Similarly, Warren Chang’s 2012 ten-year retrospective at the Pacific Grove Art Center shows the inspiration provided by Steinbeck’s rich human material—in Chang’s case, Steinbeck’s stories of marginalized Monterey County farm workers, a major subject of the author’s early writing.

Like John Steinbeck’s fiction, the paintings of David Ligare and Warren Chang are technically superb, thematically coherent, and emotionally riveting. While acknowledging Steinbeck’s impact on the development of their very different versions of visual-arts realism, each also notes the influence of European classicism in their work. Chang’s style owes much to the paintings of Jean-Francois Millet, Rembrandt, and Vermeer. Ligare notes the rules of visual arts structure exemplified by Nicolas Poussin as an influence, along with classical art and literature—a lifelong interest of John Steinbeck, who acknowledged the role of Greek and Roman authors in his literary development, as Ligare does in the visual arts.

Like Steinbeck, Chang portrays the pain of the human condition and the triumph of the human spirit: his paintings of farm workers toiling in Monterey County fields depict disenfranchised members of modern society, as Steinbeck did in his most memorable fiction of the 1930s. By contrast, Ligare’s Monterey County landscapes are devoid of human artifact or activity, relying on dramatic lighting and carefully crafted composition to suggest the tension and complexity beneath the pastoral surface. Steinbeck achieved a similar effect with words, notably the extended description of the Salinas Valley that opens East of Eden, as well as the stories, letters, and essays in which he described the Salinas of his boyhood as a placid town with an undertone of evil.

Warren Chang’s Stories on Canvas

Chang was born and raised in Monterey County and attended the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, where he received his BFA in illustration in 1981. After working as an award-winning illustrator in California and New York, he eventually returned to Monterey and transitioned to an equally successful career as a fine artist. Today he is one of only 50 artists recognized as a Master Signature member of Oil Painters of America.

Chang’s portfolio features interior and landscape subjects including portraits, still-life paintings, and scenes from his home, studio, and the San Francisco Academy of Art University classroom where he teaches. As Steinbeck observed, the visual arts, like literature, can tell dramatic stories that draw viewers into the picture—a truth demonstrated in Chang’s Monterey County landscapes, where a single moment captured on canvas suggests the ongoing narrative of which it is a part. Chang’s paintings of Monterey County field workers have been compared to the Flemish master Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Examples from Warren Chang Narrative Paintings (Flesk Publications, 2012) are shown here with the permission of the artist, whose paintings can also be seen at Hauk Fine Arts in Pacific Grove and at the Winfield Gallery in nearby Carmel. (For more information, visit Chang’s website.)

Approaching Storm

Oil on canvas by Warren Chang, 30” x 40” (2006)

Courtesy of the artist. ©Warren Chang

Approaching Storm is a dramatic study of Monterey County workers hurrying to complete the broccoli harvest before an unseasonable storm that could destroy the crop and their livelihood. Agriculture is a major Monterey County industry: the fields dotting Monterey County’s coastline and valleys produce lettuce, broccoli, and artichokes in abundance.

Day’s End portrays laborers leaving the artichoke fields near the Monterey County town of Castroville at the end of the work day. John Steinbeck, who worked alongside migrant laborers as a young man, conveyed the mood and feeling of Monterey County’s farm fields in carefully chosen words. Chang accomplishes the same purpose through deep shadows and late afternoon lighting rendered in subdued colors.

Fall Tilling recently won Best of Show in the 2013 RayMar Fine Art Competition. Except for the cell phone and Coke clutched by the female figure in the foreground of the painting, this characteristic Monterey County scene could have been painted using the same essential elements—mountains, fields, workers—at any time in the past 200 years. Chang’s reply to a question about the meaning of his works could have come from John Steinbeck, a writer who demurred when asked about the meaning of his books. “No one interpretation is necessarily more accurate than another,” says Chang. “You have the freedom to take from each painting what you will.” Ut pictura poesis: the visual arts, like literature, create images that invite us to draw our own conclusions.

David Ligare’s Paintings from the Pastures of Heaven

Unlike John Steinbeck and Warren Chang, David Ligare is not a Monterey County native. Born in Oak Park, Illinois, he traveled to Los Angeles to study at the Art Center College of Design. From there—inspired, he recalls, by the writings of John Steinbeck and Robinson Jeffers—he moved to Monterey County, where he lived and worked in a small house on the Big Sur coastline, experimenting “as young artists do, with new styles and concepts.”

Ligare’s experimentation led to a distinctive style that he describes as “Post-Modern, Neo-Classical American,” weaving contemporary retelling of Greek myths into landscapes that are instantly familiar to Monterey County residents. His paintings have appeared in numerous solo exhibitions and can be found in the collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi in Florence, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum of Art in Madrid.

The following examples of the artist’s work span the period from 1988 to the present and are shown with the artist’s permission. Several recent paintings appear in River/Mountain/Sea, the exhibition showing at the Monterey Museum of Art through April 27, 2014. Others can be viewed at the Hirschl & Adler Modern Gallery in New York and at the Winfield Gallery in Carmel. (For more information, visit Ligare’s website.)

In “John Steinbeck and the Pastoral Landscape: An Artist’s Viewpoint,” a lecture delivered in 2002 at the National Steinbeck Center, Ligare explained his purpose: “I have basically made a career of pulling the past into the present.” Landscape with a Man Drinking from a Spring is set in the Gabilan Mountains, not far from the site of Steinbeck’s novella The Red Pony. Ligare’s depiction of “a celebration of a wholesomeness that embraces both life and death”—a pervasive theme of Greek and Roman writing—shares two key symbols with Steinbeck’s description of the boy Jody, drinking from a mossy tub on the Tiflin Ranch, in the first part of The Red Pony. In both painting and story, the clear spring represents life while the cypress tree beneath which Carl Tiflin slaughters his pigs signifies death, unavoidable and often dirty.

Landscape with a Man Drinking from a Spring

Oil on canvas by David Ligare, 60 x 90 (1988)

Courtesy of the artist. ©David Ligare

After Ligare moved to Monterey County’s Corral de Tierra, the setting of John Steinbeck’s novel The Pastures of Heaven, the Monterey County landscape emerged from the background to dominate his paintings. David Ligare, a catalog published by the Hackett-Freedman Gallery in 1999, contains nine plates; six are panoramic views of Steinbeck’s heavenly valley by the artist that could easily serve as illustrations for the novel. The subject of the catalog’s cover illustration—Landscape with a Red Pony—refers to Steinbeck’s story of adolescent initiation in rural Monterey County, written when the struggling author and his wife Carol were intimately involved with Monterey County’s Depression-era visual arts scene.

Landscape with a Red Pony

Oil on canvas by David Ligare, 32” x 48” (1999)

Courtesy of the artist. ©David Ligare

Ligare explains why he likes to paint in the “golden hour” of the late Monterey County afternoon: “No matter whether I’m painting a simple rock or a figure in a landscape or a still life, it’s important to me to use the late afternoon sunlight and to create a sense of wholeness by recognizing all of the direct and indirect light sources. Everything in nature is a reflection in one way or another of everything around it.”

River is one of three monumental paintings in the River/Mountain/Sea exhibition created by the artist in homage to his adopted Monterey County. Like Mountain and Sea, it represents an iconic Monterey County location featured in Steinbeck’s fiction. Ligare’s river scene shows the Salinas River as it emerges from the valley’s mouth into its broad agricultural plain. Mountain depicts majestic Mount Toro and Castle Rock—the rock formation that fired John Steinbeck’s boyhood imagination—as shadows fill the folds on Mount Toro’s western flank. In Sea, the third painting, granite tidal rocks are lit by the last rays of the evening sun near Lover’s Point in Pacific Grove.

Visiting Monterey County? Don’t Miss Masters in Miniature

Miniatures, the Monterey Museum of Art’s annual holiday exhibition and fundraiser, features 300 paintings, photographs, prints, sculptures, and mixed media works contributed by Monterey County artists for purchase through the sale of raffle tickets. Paintings by David Ligare and Warren Chang are among the most highly sought-after works featured at the event each year. Chang and Ligare’s 2013 offerings capture the essence of their art in the 7 x 9 inch-limit format mandated by the museum for paintings contributed to the show: Ligare’s Pinax, a meticulously rendered image of a Monterey County pine cone on a polished pine wood mount, refers to Dionysus, the Greek god of wine who sported a pine cone on top of his staff. Chang’s Master Study of Velazquez’s “The Fable of Arachne” displays the artist’s trademark use of highlights and shadows in an intimate portrait of a woman winding a ball of wool. Miniatures is open through December 31. If you’re visiting Monterey County during the holidays, don’t miss it.

Photo of Warren Chang by Sonya Chang, courtesy of Warren Chang. Photo of David Ligare courtesy of David Ligare.

Robert DeMott – “Hospital Memory: Christmas, 1955”

In his later years, John Steinbeck complained about America’s decline into materialism—a state of spiritual decay he depicted as a familiar Christmas tableau: indulged children, gifts torn open and cast aside, crying to their parents, “Is that all there is?” Robert DeMott’s academic writing about John Steinbeck is the best of his generation. But his reputation as a writer of distinctive poetry—News of Loss (1995), The Weather in Athens (2001), and Brief and Glorious Transit (2007)—is equally secure: Weather in Athens was co-winner of the 2002 Ohioana Award in Poetry. Recently retired from Ohio University, Robert DeMott remembers his own father in his 2013 Christmas card poem—a reminder that the greatest gift is love.

—For James DeMott (1917-2007)

“What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?”

—Robert Hayden

Dawn came slowly to our north shore

and I rose hazy from anesthesia

to watch it steal over house tops,

church spires, and parking lots

to sweeten the courtyard where

dwarf cherry and dog wood trees

bowed in their gowns of snow.

Daylight entered that room

through thick glass walls

and fell then on presents

piled by my mother’s wishes

at the foot of the bed.

I recall each child’s thing

by color, size, heft, and could

name them, but what’s the point?

All were well used but long gone,

as holiday presents often are,

before I knew the true gift

that night was my father,

driving miles through winter

to deliver his promise while I slept.

Love New Short Stories and Novels? Good Books from Center’s Steinbeck Fellows

John Steinbeck books abound at San Jose State University, home of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies. But not all of the good books found there are about John Steinbeck. Thanks to the Center’s generous founder, Martha Heasley Cox, San Jose State University supports the creation of good books by young writers at a rate far beyond its size. Short stories, novels, memoirs, articles and essays, anthologies: good books of every variety blossom like spring flowers from the Steinbeck Fellows program, an important incubator of up-and-coming writers mentored by San Jose State University’s top creative writing faculty.

John Steinbeck books abound at San Jose State University, home of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies. But not all of the good books found there are about John Steinbeck. Thanks to the Center’s generous founder, Martha Heasley Cox, San Jose State University supports the creation of good books by young writers at a rate far beyond its size. Short stories, novels, memoirs, articles and essays, anthologies: good books of every variety blossom like spring flowers from the Steinbeck Fellows program, an important incubator of up-and-coming writers mentored by San Jose State University’s top creative writing faculty.

San Jose State University Nurtures Writers in Many Forms

The University’s busy Steinbeck Center—the most concentrated collection of John Steinbeck books and manuscripts available to readers and researchers anywhere—initiated the Steinbeck Fellows program in 2001 with a generous gift from San Jose State University Professor of English Martha Heasley Cox, a beloved Steinbeck scholar with vision, energy, and means. To date more than a baker’s dozen of new novels, numerous prize-winning short stories, and a variety of good books about Ed Ricketts, outdoor survival, life in Iran, and other compelling topics have issued from writers who apprenticed in San Jose as Steinbeck Fellows. Charles McLeod, one of 15 fellows in the program’s brief history, won a 2009 Pushcart Prize, had his first novel published by Random House UK within two years, and appeared in an anthology of best new short stories published by Norton in 2012. Sarah Houghteling, a Fellow in 2006, published Pictures at an Exhibition (Knopf, 2009), reviewed in The New York Times. Peter Nathaniel Malae, a 2008 Fellow, has published What We Are (Grove, 2010)—also reviewed in The New York Times—and Our Frail Blood (Grove, 2013).

Public Events Celebrate Spirit of John Steinbeck Books

Good books by the best young writers continue to germinate in the rich Steinbeck soil of San Jose State University, where three current Steinbeck Fellows read from their work recently for a group of eager students, fellow writers, and admiring fans. The talented trio—Vanessa Hua, Tommy Mouton, and Dallas Woodburn (shown here)—were introduced by Paul Douglass, professor of English at San Jose State University and interim director of the Steinbeck Center, where John Steinbeck books, values, and ideas are celebrated year-round in appearances by authors and artists such as Ken Burns, the boyish filmmaker who received the 2013 John Steinbeck Award for creative work embodying the progressive spirit of Steinbeck’s novels, short stories, and nonfiction. The Steinbeck Fellows reading and Ken Burns event occurred within a single week, ample evidence of San Jose State University’s extraordinary commitment to public programming. An energetic official named Ted Cady is the University’s secret weapon in the competition for marquee-event audiences from an ethnically diverse, sensory-overloaded metropolitan market of more than 2 million residents.

Short Stories and Novels in Progress Captivate Audiences

Two of the three Steinbeck Fellows read from new novels nearing completion: Vanessa, a globe-trotting journalist published in major papers including The New York Times, and Tommy, a Louisiana native with an uncanny ear for regional speech. Dallas read from one of her recent short stories, a character study of individual isolation called “Living Alone.” Each writer’s voice—pitch-perfect, in character, unmistakably original—fit like a glove. Taken together, they exemplified an essential feature of John Steinbeck books at a similar stage of development: good books are best judged at their birth, not by lines in manuscript, but by the writer’s voice, reading aloud to a group of friends like those who gathered at San Jose State University to hear the current crop of Steinbeck Fellows share their recent work. Interested? Read Dallas Woodburn’s “Living Alone,” published in its entirety for the first time online. An upcoming audio blog of Dallas reading her story is—as print publishers say of good books by promising authors—in progress. Watch this space for it early in 2014.

“Living Alone”: A Short Story by Dallas Woodburn

The thing about living alone is, you’ve got no one to scratch your back. If it’s a whisper of an itch, a fleeting thing, it can usually be taken care of by leaning casually against a doorframe and swaying back and forth. Which can actually be quite nice, scratching your back against a doorframe, especially if while you’re doing it you close your eyes and pretend you’re a willow tree in the wind, swaying, swaying. Of course you don’t look like a willow tree in the wind. You look like an insane person. But the thing about living alone is, there is no one around to see you.

But let’s say you have a more stubborn itch, like maybe you went to a party at your boss’s house and it was held on a Sunday afternoon in early September, and everyone was outside in the backyard because it was such a beautiful day and only the slightest bit muggy, and maybe your mouth was tired of talking about grown-up things so you sat in the grass with the children and knotted the throats of dandelions together in long, looping chains, and maybe you were wearing a halter top or a backless sundress and you didn’t even notice the bugs until you got home and felt the angry bumps all over your back, especially in the middle part of your back where your arms, even if you have abnormally long arms, can’t reach.

If that happens, and you live alone, the best thing to do is to strip off all your clothes and turn the shower on lukewarm and let the water beat down upon your itchy back, and you can even close your eyes and pretend it’s a person there, gently scratching your itchiness away. In fact, it’s good you live alone because a person’s general tolerance for back scratching wears thin after only a few minutes, but you can stand under the shower for a long time. You can stand under the shower until the water turns from lukewarm to kind of cold to so cold you can’t stand it any longer. And if, when you step out of the shower, you drip a trail of water on the floor all the way from the bathroom down the hall to your bedroom, you won’t have to worry about anyone slipping on it, or asking you to clean it up, or doing that annoying roommate martyr routine of cleaning it up without saying anything to you but adding a little checkmark to the running tally in their head of All The Ways In Which You Are a Horrible Human Being.

*

I once dated a guy named Phil who was deaf in his right ear. At the time, I didn’t have a car, and he didn’t like me driving his car, so whenever we went anywhere he did all the driving. Sometimes, on the highway, he’d roll down the windows so the air flapped around us like birds’ wings. I’d be halfway through a convoluted story when he’d glance at me, a placid nonexpression on his face, and I’d realize I’d been talking and talking and talking and talking and he hadn’t heard a single word.

*

When I moved away to college, I missed my mother a lot, but I didn’t want her to know I was missing her because I felt like then she would win. I don’t know what game we were playing, but it seemed important, and the rules were very clear to me. If my mother knew how much I missed her, knew about the cloying homesickness twisting my insides like the stomach flu, something between us would change. So, whenever I wanted more than anything to call her, I would eat instead. I would eat whatever I could find nearby with the lowest nutritional value. See, I would tell myself, this is the best. Mom would never let you eat Skittles and Cheese-Whiz for dinner. Eventually the homesickness would morph into normal, food-induced stomach pains, and then I would feel better.

*

The thing about living alone is, you can walk around naked and eat dinner naked and dust the bookshelves naked. You can stand naked in front of the mirror with your hands on your hips and your hair in a towel turban and flirt with your foggy reflection. You can sing naked karaoke. Out of all the karaoke songs in the world, you can choose “My Heart Will Go On” by Celine Dion and since you live alone no one will be there to groan at you and roll their eyes and pretend to vomit.

“But being naked is better when you’re naked with someone else,” says my friend Minnie, who was named after the mouse, and who has lived with Craig for three years and five months. Before Craig, she lived with Roger, and before Roger she lived with Steve, and before Steve she lived in an all-girls dormitory at Scrips.

“You don’t know the first thing about living alone,” I say.

Minnie thinks I mean it as a compliment. “Thank you,” she says, smiling at me. Whenever Minnie smiles her eyes get squinty. I have known her for seven years and I have never seen a wide-eyed Minnie smile, not even when she is drunk or surprised or trying to look good for a photograph. In photographs, it always looks as if she is squinting directly into the sun.

*

I glance out my kitchen window and there she is, Becky, walking down the sidewalk, around towards my front door.

Actually the person walking past doesn’t look anything like Becky. Her hair is short and her face is pinched.

But in my mind, she is Becky, coming around my house to knock on my front door, wanting something from me, wanting to talk to me. I leave my oatmeal half-cooked and duck into my bedroom, and once I am in my bedroom I head straight for my closet. I slide the door shut behind me. I sit there for a while, listening to my own breathing, as I wait for the knock to come on my front door.

It never comes.

Becky must have changed her mind and turned around. Which is a relief, really. I meant it when I said I never wanted to talk to her again.

*

The thing about living alone is, you can go days without talking to anyone. Like maybe when you leave work on Friday you say, “Goodbye” to the person the next cubicle over from you, but then your best friend is away for the weekend with her boyfriend at a Bed & Breakfast in Carmel, and the staff at Cypress Gardens don’t like for your mom to talk to you on the phone because of what happened the last time, so maybe you spend the whole weekend watching Saved By The Bell reruns in your bathrobe covered with kittens, and you go into work on Monday and Shelly the next cubicle over from yours asks, “How was your weekend?” and when you say, “Oh, fine,” your voice is rough and croaky because it hasn’t been used in a while.

*

It took a long time for me to break up with Phil. It took a lot of practice. We’d be driving down the highway, the windows cracked a few inches, the breeze like the muffled applause of a crowded room, and I would say to Phil, “You know, maybe we should break up.”

I’d say, “This isn’t working for me anymore.”

I’d say, “We’re just too different.”

One time, Phil glanced over and saw my lips moving. “What?” he asked.

I shook my head, retreating, not ready. “Nothing,” I said. “Just talking to myself.”

Phil smiled, reached over and squeezed my knee. Three months later, after our relationship imploded in an Applebee’s parking lot, he said, “You know, I’ve seen this coming for a long time.” And I thought about all our car rides and I wondered if maybe I was the one who was missing something.

*

When my mother began to lose her mind, I took a week off work to help her get moved into Cypress Gardens. I was anxious on the plane ride there, full of nervous energy. I kept getting up to stretch my legs, pace the aisle, use the tiny plane bathroom. But when I met my mother at her house, at the old brick house with the wide yard I’d grown up in, everything was as it always was. She seemed fine, perfectly lucid, her hair neatly parted and brushed as always, her lipstick perfectly applied. She thought Cypress Gardens was a nice hotel we were going to for a vacation. She looked around her new one-bedroom apartment, with the heavy curtains and the thick carpet, and said, “My goodness, Lena. Are you sure you can afford this?”

When I left, I hugged her fiercely and said I’d be back soon. The air was cold and burned my cheeks, and tears blurred my vision.

They found the brain tumor after my mother became convinced I am not her real daughter but rather an alien lifeform impersonating myself.

“Give me back my Lena!” she screamed into the phone the last time I called.

“Mom, it’s me.”

“You’re a liar! Don’t try to trick me! Where is she? What did you do with her?” Then she was screaming my name, over and over. The nurses had to sedate her.

I was supposed to fly out three weeks ago to see her. I got all the way to the freeway exit for L.A.X. but then I couldn’t go any further. I kept driving, four exits, ten exits, thinking of the way my mother used to stir sugar packets into her iced tea, delicately, the spoon never once clinking against the glass. At the fourteenth exit, I got off, turned around, and drove back home.

*

My mother met my father on an airplane to Chicago. She was flying there to visit her older sister in college. My father was flying there on business. My mother said he coaxed her into conversation with a corny joke about an elephant in a fridge. “He waited to laugh until I did,” she said. “I liked that. Your father had a very nice laugh.”

They wrote letters, and two months later when she graduated high school, my mother moved to Toledo, where my father lived, to go to college. She dropped out after only one semester and married him. He died when I was fourteen. She never remarried.

*

When Becky told me she was moving out, her face had a blankness to it, a coldness. I felt as if she’d punched me. We’d been living together for four years, since right after college – first a dumpy, tiny flat in Venice Beach, then a bigger apartment in Brentwood. We’d bought furniture together. We’d picked out dishware. We decorated for holidays. I knew one or the other of us would move out eventually, but I didn’t expect it to be like it was – Becky’s sudden, casual announcement, like she was telling me she forgot to get peanut butter at the grocery store. I’d assumed that when one of us decided to move out, there would be crying over bottles of wine, tight hugs, fierce promises to come visit, to stay in touch always, always.

It was terrifying, that something I’d felt so sure and safe about could end so abruptly. A light switch flicking off. What about all the hours we’d spent talking at the kitchen table, our beat-up kitchen table we’d salvaged from that yard sale in Little Tokyo? What about all those late nights we’d turned on the stereo and danced around the living room until we collapsed? What about our joined routines, our rituals, our inside jokes, our encyclopedic data bases of minute facts about each other – Becky’s fear of tornados, my love of all things polka-dotted; Becky’s school picture with the gum in her hair circa 1984, my dime-sized knee scar from a childhood skating accident. Didn’t all that count for something? Because it should. I felt sure it should.

But, from the way Becky was acting, it seemed I was nothing more than a roommate, flung into her life by circumstance, and just as indifferently tossed away. When I came home from work, her bedroom door was often shut; boxes began to spawn in the living room and the kitchen, slowly filling with her things. She tried to claim some of the things we’d bought together, an argument that ended with me weeping, clutching a blender to my chest, screaming that I wouldn’t let her have it.

“Jesus, Elena,” Becky said, her mouth cinched tightly in disgust. “Fine, take the damn blender.”

As soon as she said that, I couldn’t bear to hold it any longer. I threw the blender across the room and told Becky I never wanted to see her again.

I began to question all my relationships. I picked fights with Minnie. I grew suspicious of Phil. Maybe he was hiding something, too. Maybe he secretly despised me. Maybe, I thought, I should break up with him before he could break me.

*

The thing about living alone is, there is always too much food. The people who designed food packaging did not consider those of us who live alone. You can never drink a whole carton of milk before it spoils. You can never eat a whole loaf of bread before it molds.

At the grocery store, I splurge on fancy whipped cream cheese, even though I only eat bagels occasionally. Becky was the one who loved bagels. Bagels and lox. Sometimes on Sundays she’d come home with a paper bag from Noah’s Bagels, filled to the brim. And we’d eat them. The ones we didn’t eat, we’d tear up into little pieces and feed to birds at the park. Food never spoiled when I lived with Becky.

*

One time, as we drove down the highway with the windows cracked and flies occasionally smattering the windshield like clouds of regret, I told Phil I loved him. He turned towards me, grinning widely. He said, “Did you see that Billboard we just passed? Someone graffitied a mustache on Sarah Palin.”

*

After I graduated college – Art History major – I had trouble finding a steady job. I worked for a few months as an English tutor, a film gopher, a smoothie barista. My mother wanted me to move back home to Toledo. She didn’t think California was a place where good people lived. “You’ll never find a husband there,” she said. “Those hippies don’t like to settle down.”

I told her the hippies lived in Berkeley, not L.A. She sniffed dismissively. I sent her pictures of me and Becky – standing proudly in our newly furnished apartment, smiling in the foamy waves at the beach. Still, every time I called home, my mother’s first question was if I’d met someone yet.

“I worry about you, Lena,” she’d say. “I don’t want you to end up alone.”

“I won’t.”

“You don’t understand, baby girl. It’s the worst kind of emptiness, living alone.”

“I won’t end up alone,” I’d tell her. “I promise.”

*

Minnie and I meet for lunch at The Urth Caffé so she can tell me about her trip to Carmel. She shows me pictures on her digital camera, the two of us leaning in close to the tiny screen. Minnie’s face smells powdery in a pleasant way. I want a powdery face. My face feels greasy and porous in an unpleasant way. All the pictures of the ocean make me want to drink water, and all the water I drink makes me have to pee.

“I’ll be right back,” I say, scooting back my chair and standing up.

I am only gone a few minutes, but when I return, Becky is in my seat, scooted up close to Minnie, peering down at the tiny digital camera screen. I have a strange sense of déjà vu, or maybe it’s more of an out-of-body-experience – as if I have stumbled upon a different version of myself, in a different version of my life.

I step backwards, bumping into a waiter. His carefully balanced tray wobbles but he steadies it. “Sorry,” I say, fleeing out the back exit. I wish I were wearing a billowy silk scarf. That I had something billowing out behind me to announce the absence of my presence.

*

On the day of the big move, I refused to help Becky carry her boxes down to her friend Steve’s van. I stayed in my room, the door locked, blasting the Ramones on my stereo. We did not say goodbye. If she knocked on my bedroom door, I did not hear it. When I finally emerged that night, the apartment felt like a tomb.

I called Phil and told him how empty the apartment was. “It’s so lonely in here,” I said. “It feels so big. Like I’m living inside a whale’s mouth.”

I wanted Phil to ask what kind of whale, but he didn’t. He just said he’d be right over. I waited for him in the living room, sitting on the edge of the coffee table because Becky had taken the couch. When he knocked on the door, I knew it was him – but part of me still leapt inside, thinking of Becky, of all the times she had locked herself out. She was always forgetting her key. Our front door opened out onto an open-air hallway, and I’d drive home early from work to let her in so she wouldn’t have to wait outside for an hour. She taught first grade so she was off around four every day. “My rescuer!” she’d exclaim when I’d appear at the top of the stairs. “Thank you, thank you, I’ll buy you some booze!”

Phil and I slept together in my bed, which we’d done countless nights before, but it felt different now without Becky across the hall.

“Move in with me,” Phil whispered. I pretended I was already asleep, because I wasn’t sure what to say. I wasn’t sure what I wanted.

The next morning, Phil walked around naked, his penis swinging everywhere. It was strange to see his penis swinging around in my kitchen. He looked so carefree, like this was normal, and maybe it was, maybe it would be the new normal. Me and Phil, buying furniture and dancing past midnight and putting up holiday decorations. Me and Phil, walking around naked and fucking anywhere we wanted because we didn’t have to worry about a roommate walking in on us.

The blender was still in the corner where I’d thrown it, looking hurt and ugly, the cord flung out like a desperate drowning arm.

I realized, within the next few days, that my feelings for Becky were deeper than I’d ever felt for Phil, and that I missed Becky more than I’d ever missed Phil. Suddenly I felt sick that Phil and I had lasted this long, that I had let things get to this point. We were settled. Comfortable. It was perfectly normal for him to ask me to move in with him.

Two days later, when Phil picked me up for our Friday dinner date, I couldn’t summon the enthusiasm to suggest a place. We ended up driving around aimlessly for a good twenty minutes before he finally swerved into the parking lot of Applebee’s. “I could do with some riblets,” he said, exaggerating his Southern drawl, showing off for me. I remember his earnest smile as he cut the engine and unbuckled his seatbelt, how carefree he looked in that moment. Riblets, beer, Friday night. Then he glanced over at me and his features drew in, his gaze sharpened. “What is it, Lena? Don’t cry, baby. What’s wrong?”

*

When Phil and I had been dating for three weeks – long enough that we felt relatively solid, that I still liked him, that he still called me – I felt comfortable telling my mother. I could hear her beaming over the phone. I shared the basics: grad student, Cal Tech, mechanical engineering, twenty-eight, never married, no kids.

“He sounds wonderful,” she said, over and over. “Wonderful.”

I couldn’t remember the last time she’d sounded so proud. So relieved.

*

I’ve been home for only a couple minutes when my phone rings. “What is up with you?” Minnie asks, her tone accusing. She must be on her cell phone, leaving The Urth Caffé. Wind cuts into her mouthpiece, drowning out her voice.

“What?” I say. “I can’t hear you.”

“Why’d you take off and leave me like that? You just disappeared.”

“I told you, I had to use the bathroom.”

“Yeah, but then you never came back.”

I tell her that I did come back. “I saw you,” I say. Now my tone is accusing. “I saw you with her.”

“With Louise? Why, do you know her or something?”

“Who’s Louise?”

“Craig’s sister. She was eating a few tables over from us.”

“Oh.” I sit down on my red couch and hug a throw pillow to my chest. “No, I don’t know her. I thought she was someone else.”

“Who?”

“It doesn’t matter. I’m sorry.”

“Elena,” Minnie says. Abruptly, the wind stops, and her voice sounds clear and close. “Becky lives in Toronto now, remember?”

“Yeah.”

“And it wasn’t about you. It didn’t have anything to do with you. Sometimes people just need to move on. Life changes.”

“Yeah.”

“Are you okay? I worry about you.”

“I’m fine,” I say. “Don’t worry. I’m fine.”

*

“You’re crazy!” Phil said that night in the Applebee’s parking lot.

“I’ve seen the way you look at her.”

“When am I even around her to look at her? It’s not like she’s ever at your place when I’m there.”

“See! Suspicious. It’s like the two of you are hiding something.”

“Lena, really, you’re being insane. I can’t even remember the last time I saw Becky. She’s hardly been around at all the last few months.”

I looked down at my lap, at my hands holding each other. “I don’t love you,” I said. “I’m sorry, but I don’t.”

So instead of moving in with Phil, I moved into a one-bedroom apartment on the other side of town, and I bought a bright red couch and casually mismatched pillows and a potted begonia for my windowsill. Sometimes at night, while watching TV, I look down at my hands, on my lap, holding each other.

*

The thing about living alone is, you have no one to double-check the locks. You climb into bed and turn off the light, and just then you hear a noise – a creak of the floorboards as the house resettles itself; the scratching of a tree branch against the windowpane. And you feel cold, and very alone, and you think of all those stories on the news about people living alone, young women especially, who get robbed or raped or murdered, and no one finds them for days and days, and you know it’s old-fashioned to want a man to protect you, but really you just want someone, anyone, anyone else to climb out of bed and go check the deadbolt on the front door, to make sure it’s bolted securely shut. But the thing about living alone is, there is no one else. There is only you. So you climb out of bed, hugging yourself against the chill, turning on lights in the bedroom, the hallway, the living room, the entryway, as you venture up to the front door, your own eyes shadowy hollows in the black pane of glass, and you see – there – relief – it’s locked. You touch the deadbolt, you feel its weight beneath your fingers, just to be sure. It’s locked, it’s locked. You retreat back to your bedroom, turning off lights as you go, feeling better but still alone. And then you climb beneath the covers, pull them up to your chin, turn to one side, then the other, waiting for your body heat to warm them up, waiting, waiting.

A Meeting of Minds on Cannery Row: John Steinbeck’s Phalanx, Carl Jung’s Types, and James Kent’s Gathering Place Roles

Some years ago my paper on John Steinbeck, Carl Jung, the phalanx, and the Development of Higher Management Teams was published by an online forum devoted to the life and work of the Swiss psychologist and psychiatrist Carl Jung. At the time I was developing team and organization building programs for corporations. My job required some business travel. While in California I did what other Steinbeck lovers do: I took a side trip to Monterey’s Cannery Row. What follows further develops my recent post on John Steinbeck, Carl Jung, and how their insights can be applied in business.

Fellow Pilgrims to Cannery Row Discover a Mutual Interest

Sometime before my pilgrimage to Cannery Row, I received a call from James Kent (shown below), a John Steinbeck fan who also recognized the practical value of Steinbeck’s work beyond its entertaining read. He told me that he found my phalanx paper and thoughts interesting. We agreed to meet on Cannery Row to talk in person. On a walk down the hallway of our Monterey motel, Jim mentioned his concept of Gathering Place roles and how his team uses it in their initial analysis of informal network gatherings in restaurants, barbershops, and taverns in communities facing challenges. Jim and his team discovered the true nature of public attitudes and resistance within these gatherings beneath the sanitized version frequently presented by public officials. I thought the idea was brilliant and I said so.

I also thought that the concept could be applied in team analysis and building within large organizations—and I still do. This made my connection with Jim and his ideas on Cannery Row that day a particularly fortunate synchronistic experience. If one accepts Jim’s Gathering Place concept, it seems natural to me to consider its relationship to ideas expressed in John Steinbeck’s writing about the phalanx and Carl Jung’s analysis of personal and collective unconscious, functional types, and attitudes.

Steinbeck and Ricketts’ Non-Teleological Way of Thinking

To develop a personally useful understanding of phalanx, one must employ a perspective that does not require a cause-effect relationship common to some scientific research. In other words, with this non-teleological perspective the researchers eliminate the influences of hopes, fears, and expectations in their planning and study. (Please refer to the Pygmalion effect or Rosenthal effect.) Such a perspective enables the researcher to drill through the illusions and brings the subject closer to John Steinbeck’s friend Ed Ricketts’ goal of “true things.” The perspective enables increased objectivity and reduces human subjectivity, projection, and slant. Scientific psychology research has a handicap that is not an issue in other empirical sciences, and that is the study instrument (the individual human psyche) must be used to study individual human psyches. No other science has such a threat to objectivity. As a result, a non-teleological perspective is essential to psychological study objectivity.

In The Log From the Sea Of Cortez, John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts stated the following regarding teleological and non-teleological thinking:

What we personally conceive by the term “teleological thinking,” as exemplified by the notion about the shiftless unemployed, is most frequently associated with the evaluating of causes and effects, the purposiveness of events. This kind of thinking considers changes and cures—what “should be” in the terms of an end pattern (which is often a subjective or an anthropomorphic projection); it presumes the bettering of conditions, often, unfortunately, without achieving more than a most superficial understanding of those conditions. In their sometimes intolerant refusal to face facts as they are, teleological notions may substitute a fierce but ineffectual attempt to change conditions which are assumed to be undesirable, in place of the understanding-acceptance which would pave the way for a more sensible attempt at any change which might pave the way for a more sensible attempt at any change which might still be indicated. Non-teleological ideas derive through “is” thinking, associated with natural selection as Darwin seems to have understood it. They imply depth, fundamentalism, and clarity—seeing beyond traditional or personal projections. They consider events as outgrowths and expressions rather than as results; conscious acceptance as a desideratum, and certainly as an all-important prerequisite. Non-teleological thinking concerns itself primarily not with what should be, or could be, or might be, but rather with what actually “is”—attempting at most to answer the already sufficiently difficult questions what or how, instead of why. An interesting parallel.

The powerful, unconscious, and autonomous influence on individual perception, judgment, conclusions, problem solving, decisions, and behavior, within an objective-focused gathering, group, or MOB, is what John Steinbeck called the phalanx. The MOB objective may be unreasonable or illusory, but may cause members to participate in scape-goating or group bullying of those who simply disagree with their beliefs. I believe there are few things in this life more worthy of scholarly examination than the phalanx phenomenon. The concept is based somewhat on the collective unconscious described by Carl Jung and by other philosophical giants including Harvard Professor William James, a major influence on Jung also familiar to Steinbeck, who coined the term phalanx, clearly defined it, and applied the concept in his novels.

Carl Jung’s Types and Jim Kent’s Gathering Place Roles

Jim Kent’s Gathering Places for friends in a network are casual happenings. (John Steinbeck in Sweet Thursday: “In the Palace Flop house a little meeting occurred—occurred, because no one called it, no one planned it, and yet everyone knew what it was about.”) Informal Gathering Place roles are casually filled without formal election or appointment. I think individual styles role players gravitate naturally to their position. While I have no supportive data for this theory, I honestly believe such research would show that particular roles would naturally be filled by specific functional types—Sensation, Thinking, Intuiting, and Feeling—and attitudes: Extraverted, and Introverted. (There will be much more about the functions, attitudes, and types in my sequel to this article.) In my opinion, for example, Ed Ricketts was an “Introverted Sensation Feeling” type and as a result would fit nicely within Jim Kent’s “Caretaker” role as he specified.

Jim Kent’s Gathering Places for friends in a network are casual happenings. (John Steinbeck in Sweet Thursday: “In the Palace Flop house a little meeting occurred—occurred, because no one called it, no one planned it, and yet everyone knew what it was about.”) Informal Gathering Place roles are casually filled without formal election or appointment. I think individual styles role players gravitate naturally to their position. While I have no supportive data for this theory, I honestly believe such research would show that particular roles would naturally be filled by specific functional types—Sensation, Thinking, Intuiting, and Feeling—and attitudes: Extraverted, and Introverted. (There will be much more about the functions, attitudes, and types in my sequel to this article.) In my opinion, for example, Ed Ricketts was an “Introverted Sensation Feeling” type and as a result would fit nicely within Jim Kent’s “Caretaker” role as he specified.

Of the Introverted Sensation Type, Carl Jung said:

If there were present a capacity and readiness for expression in any way commensurate with the strength of sensation, the irrationality of this type would be extremely evident. This is the case, for instance, when the individual is a creative artist. But, since this is the exception, it usually happens that the characteristic introverted difficulty of expression also conceals his irrationality. On the contrary, he may actually stand out by the very calmness and passivity of his demeanour, or by his rational self-control. This peculiarity, which often leads the superficial judgment astray, is really due to his unrelatedness to objects.

If we include the influence of the Feeling function as an auxiliary to his Sensation type, then we are implying a strong tendency to perceive with a lean toward the interpersonal. This is my opinion based upon what information I’ve read about Ricketts. Jim’s Gathering Place roles are readily summarized and often exemplified in Steinbeck’s fiction, including Cannery Row.

Gathering Place Roles with Examples from Cannery Row

Caretakers

Are the glue that holds the culture together.

Are routinely accessible to people of the networks when they need assistance or advice.

Give assistance or advice freely; there is no chit or payback expected.

Are invisible to outsiders and do not belong to formal groups.

Are essential to high levels of social capital in society.

Ed Ricketts was a Caretaker, as is John Steinbeck’s character, the madam Flora (Fawna).

Communicators

Move information throughout the networks.

Are generally in places where they come into contact with people from various informal networks and formal groups.

Are especially prevalent in gathering places such as coffee shops, bars, beauty shops, restaurants, etc.

Are essential for moving information quickly throughout a community when you need accuracy and word-of-mouth speed.

John Steinbeck’s strike-strategist Mac is a Communicator between networks in In Dubious Battle. In Tortilla Flat Danny is a Caretaker/Communicator; Wing Chung is a Communicator.

Storytellers

Carry the culture through their stories.

Provide a community with the culture benchmarks that are essential to understand how a community can grow and still maintain the good parts of their culture.

Understand the importance of gathering places and are often the “characters” in the gathering places.

George in Of Mice and Men is a Storyteller. Of course the character Doc is cast as a Storyteller in Cannery Row, and the whole Lab actuality functions as a gathering place where stories bring understanding, introspection, reflection, and action.

Gatekeepers

Function as a protective device for the informal systems screening out intrusive people from formal systems.

Narrow the entry to a network or community through information control.

Are often verbal people who understand both the informal and the formal.

Authenticators

Function in the area of knowledge and wisdom.

Have knowledge and wisdom from the culture and often provide cultural interpretations to technical data and information generated by formal systems. Often these individuals have one foot in the cultural context and another in a scientific context understanding both as well as how to integrate so that scientific data can be put into a local context that is usable.

The Seer in Cannery Row is an Authenticator for Doc. Former Ricketts-lab key holder Eldon Dedini operates in this capacity in relation to the real-life lab and its function. Lab gathering place regular Bruce Aris was such a person, as was Ed Ricketts.

Applying the Gathering Place Concept in Your Own Group

I’d like to add my opinion that if one were to include the Jungian concept of Psychological Type to the role definitions, it may become even a more powerful tool than it is. Still, the recognition of the concept was brilliant. Think of an informal gathering of friends. Most of us would predict the likelihood that among the group are individuals filling roles as described by Jim Kent. In any network there are individuals who complement each other and other pairs who grate on each other’s nerves but tolerate the irritation for the good of the fellowship. I believe that there are gathering place role owners who, simply because of their opposing styles, may be irritants to one other. For instance, a Gatekeeper’s style may sharply contrast with that of a Communicator. A preponderance of such interpersonal connections either way will influence the social environment AND the group’s relationship to the phalanx.

Using Carl Jung’s type concept, imagine a role filled by an Introverted Intuitive Thinking type, complete with his or her grand visions, long-term plans, flow charts, logistics, cold and impersonal logic, and another role filled by an Extraverted Sensation Feeling type with interpersonal objectives, stories of previous experiences, etc. They are opposites who can either (1) let petty differences fester to the detriment of the group’s social atmosphere or (2) acknowledge that their negative emotions come out of weaknesses that are contrasted in the persona of the other individual. When this is acknowledged, the two may personally benefit from the awakening, celebrate, and value their complementary styles. The latter possibility will add to the quality of the social atmosphere and will (1) make the group less vulnerable to the negative influences of phalanx and (2) empower the network to strength far beyond its apparent resources.

Photo of James Kent courtesy Wesley Stillwagon.

This is the second in Wesley Stillwagon’s series on the application of John Steinbeck and Carl Jung’s insights in innovative corporate training program design. To be continued.

Civil War-Dust Bowl Director Ken Burns Receives 2013 John Steinbeck Award

Ken Burns, America’s greatest living documentary filmmaker, discussed his Civil War and Dust Bowl classics and previewed his new film, The Roosevelts, during San Jose State University’s December 6 event honoring him with the 2013 John Steinbeck Award. Burns joins a pantheon of progressive American artists—Bruce Springsteen, Arthur Miller, Sean Penn, Studs Terkel, John Sayles, Joan Baez, Michael Moore, Garrison Keillor, Rachel Maddow, John Mellancamp—previously honored by SJSU’s Martha Heasley Cox Steinbeck Studies Center for inspiring hope “in the souls of the people” through their creative work. Steinbeck’s timeless phrase—also the name of the award—appears in Chapter 25 of The Grapes of Wrath.

Ken Burns, America’s greatest living documentary filmmaker, discussed his Civil War and Dust Bowl classics and previewed his new film, The Roosevelts, during San Jose State University’s December 6 event honoring him with the 2013 John Steinbeck Award. Burns joins a pantheon of progressive American artists—Bruce Springsteen, Arthur Miller, Sean Penn, Studs Terkel, John Sayles, Joan Baez, Michael Moore, Garrison Keillor, Rachel Maddow, John Mellancamp—previously honored by SJSU’s Martha Heasley Cox Steinbeck Studies Center for inspiring hope “in the souls of the people” through their creative work. Steinbeck’s timeless phrase—also the name of the award—appears in Chapter 25 of The Grapes of Wrath.

From the Civil War to the Dust Bowl and the Roosevelts

During an onstage conversation with public TV-radio host Michael Krasny of San Francisco’s KQED, co-sponsor of the John Steinbeck Award event, Ken Burns described his four-decade directorial career as a voyage of self-discovery among subjects selected after months of planning from a diversity of tempting topics. Rather than teaching viewers didactically, he noted, “We say, ‘Watch what we just discovered.’” He admitted that he interviewed Arthur Miller for his first film, on the Brooklyn Bridge, without reading Miller’s play A View from the Bridge before driving to the reclusive author’s Connecticut getaway, where the 6-foot, 6-inch Miller refused to let him inside the house. The small, slim filmmaker, in his 20s and lugging a heavy camera in the dying rural light, recovered fast, using Miller’s entire interview to conclude the documentary. It was the first and last time he included a complete interview with anyone in a film on any subject.