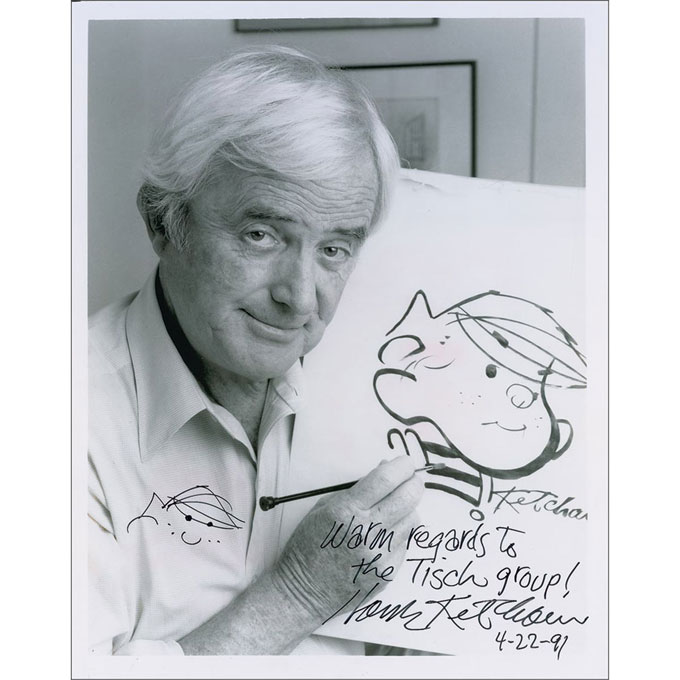

A December 20, 2018 piece published by The Independent to mark the 50th anniversary of John Steinbeck’s death could be the best writing about Steinbeck in a milestone year for journalism devoted to an author who still makes waves. The compelling profile of Steinbeck by Martin Chilton, culture editor of England’s Telegraph chain, describes “a flawed genius” who was chronically ill, frequently angry, but never inconsequential. “When I met the singer and actor Harry Belafonte,” recalls Chilton, who also writes about sports and music, “he told me Steinbeck ‘was one of the people who turned my life around as a young man,’ inspiring ‘a lifelong love of literature.’” Chilton’s take on Steinbeck’s life turns on milestone events—brushes with death, bouts of depression, divorces and disappointments—whose cumulative weight made Steinbeck “Mad at the World,” the title of the biography by William Souder scheduled for publication by W.W. Norton in 2019. A quotation from our 2015 interview with Souder includes a hyperlink to Steinbeck Now, making 2018 a milestone year for us too.

Photo of Martin Chilton courtesy of the Telegraph newspaper group