Of the four gospels, Steinbeck’s favorite was the one written by John. He paraphrased it loftily in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, and he was partial to its name. Mining the books of the Bible for material was standard procedure for writers of his generation, but the Gospel According to St. John had special meaning for Steinbeck. Written some time after the so-called synoptic gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke, John’s version is distinctive because it put Jesus’s life story in a new light, building on the narrative contained in the earlier accounts while differing in style of writing, selection of events, and point of view about Jesus’s nature and purpose on earth, adding value to the picture by looking at Jesus in a new way.

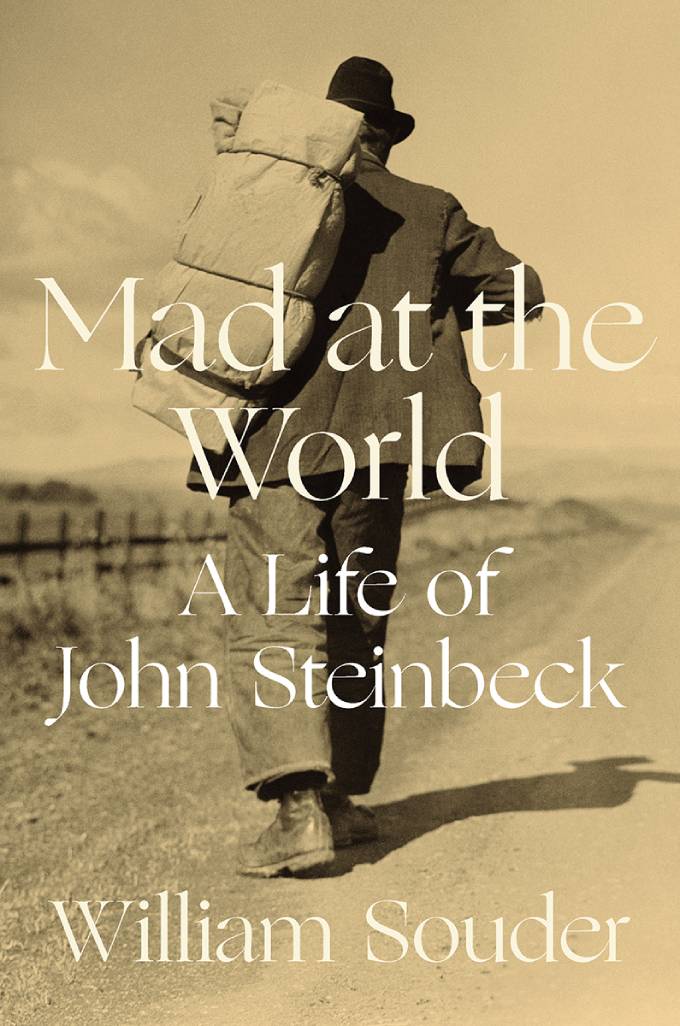

William Souder’s Mad at the World (2020), the first commercially published life of John Steinbeck in a generation, has a similar relationship to the comprehensive biographies of Steinbeck written by Jackson Benson—The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer (1984)—and Jay Parini John Steinbeck: A Biography (1994). In biblical terms, Benson is the St. Mark of Steinbeck biography—the first to tell the subject’s life story so fully—and Parini is like Matthew or Luke, making minor adjustments without changing basic facts or challenging basic beliefs. Like St. John’s gospel, Souder’s life of Steinbeck represents a departure, written in an informal style for a contemporary audience. Free from the high-level interference that inhibited Benson and touched Parini, it adds dramatic new detail and depth to our understanding of Steinbeck’s nature, psychology, and relationships. Reviewer response since the book’s publication in October shows why it needed to be written, and why anger was the right rubric for a 21st century study of Steinbeck’s life, work, and continued relevance.

The Wrath of John Steinbeck

The first published reference to anger as Steinbeck’s governing principle appears to have been The Wrath of John Steinbeck, or St. John Goes to Church, a pamphlet privately printed in 1939 by the young friend from Berkeley with whom Steinbeck stayed over Christmas in 1920, when he worked at a department store in Oakland instead of going home to Salinas. The first published review of William Souder’s Mad at the World appears to have been the September 14 review by Donald Coers here at Steinbeck Now. Coers—a veteran educator and the author of a pioneering 1991 study, John Steinbeck as Propagandist—celebrates Souder’s contribution to the edifice of understanding begun by Benson, now 90, more than 50 years ago. To put the connection in perspective, he quotes the blur for Benson’s book written by John Kenneth Galbraith. “Disproving Galbraith’s claim that no new life of Steinbeck would ever be needed,” says Coers, “Mad at the World seems certain to join existing biographies on the bookshelves of present and future Steinbeck fans, especially in America, a country whose history pervades William Souder’s writing, as it did Steinbeck’s.”

Writing for the October issue of BookPage, Henry L. Carrigan made the case for Steinbeck’s continued relevance in layman’s language designed, like Souder’s, to appeal to readers who are less familiar with footnotes than Facebook, and less likely to buy a 1,116-page book weighing four pounds than one that is half as long and half as heavy. “Steinbeck was a born storyteller who was a bit out of step with his times,” said Carrigan, because “many of his social realist novels appeared during the innovations of modernism.” But we live in an age of March madness and post-modernism, and “Steinbeck remains widely read and relevant today, as vibrantly illuminated by Mad at the World.” When The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer was written, Steinbeck needed defending from academics and the critical mafia in New York. Four decades later, Souder is defending against a different kind of disregard: the neglect that results when new readers lose interest in what an old writer has to say.

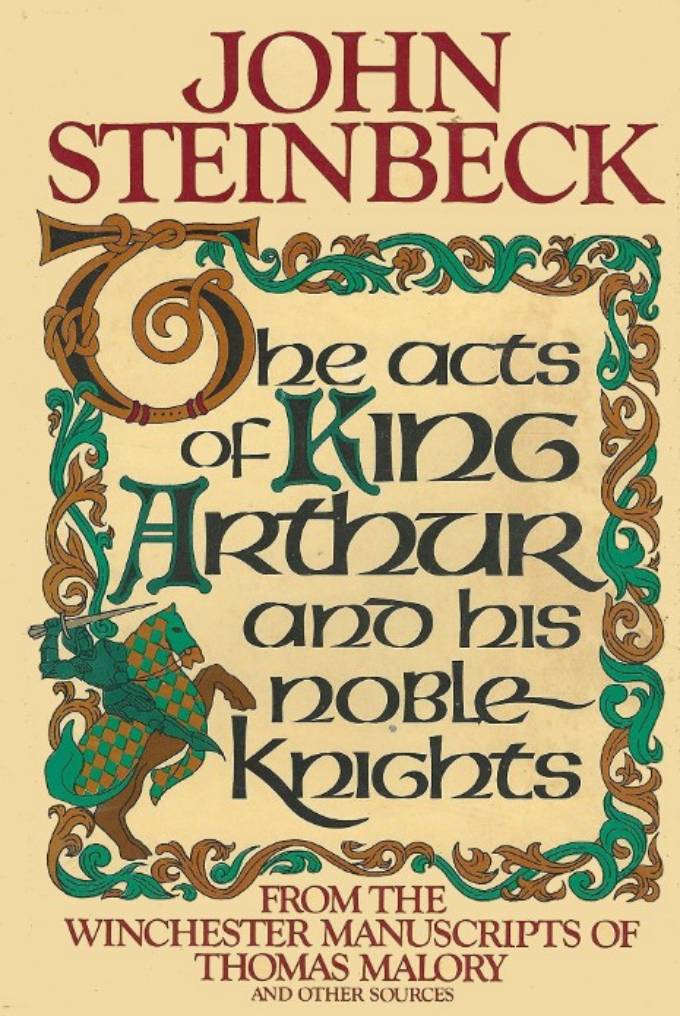

The problem of reader ignorance and indifference occupied Steinbeck, who insisted that his readers would get out of his writing only as much as they were willing (or able) to put in. Souder is an investigative reporter with experience helping newspaper readers understand science, and he leaves little to chance in this regard, providing fact-filled mini-histories of the individuals and events that influenced Steinbeck’s life and thought. These include names already familiar to Steinbeck fans—the Wagner brothers and the sisters Kashevaroff, Carlton Sheffield and Carl Wilhemson, Toby Street and Edith Mirrielees, Carol Henning and Gwyn Congers, Ed Ricketts and Joseph Campbell, Elizabeth Otis and Annie Laurie Williams, Ben Abramson and Pascal Covici—along with less familiar figures from Steinbeck’s unsteady orbit: his Stanford girlfriend Katherine Bestwick, the Albee brothers of Los Angeles, and three critics—Edmund Wilson, Orville Prescott, and Mary McCarthy—who resisted his gravitational pull. Particularly helpful for readers who are new to Steinbeck, or unfamiliar with modern history, are the profiles of movements and men who shaped the context and content of Steinbeck’s writing, from Cup of Gold (1929: Lost Generation, stock market crash, rise and fall of Herbert Hoover) to The Grapes of Wrath (1939: Great Depression, Dust Bowl, rise of Roosevelt, Hitler, and Edward R. Murrow), The Moon Is Down (1942: fall of Norway, rise of Japan), and Travels with Charley (1962: John Kennedy, Cold War, and the Cuban missile crisis).

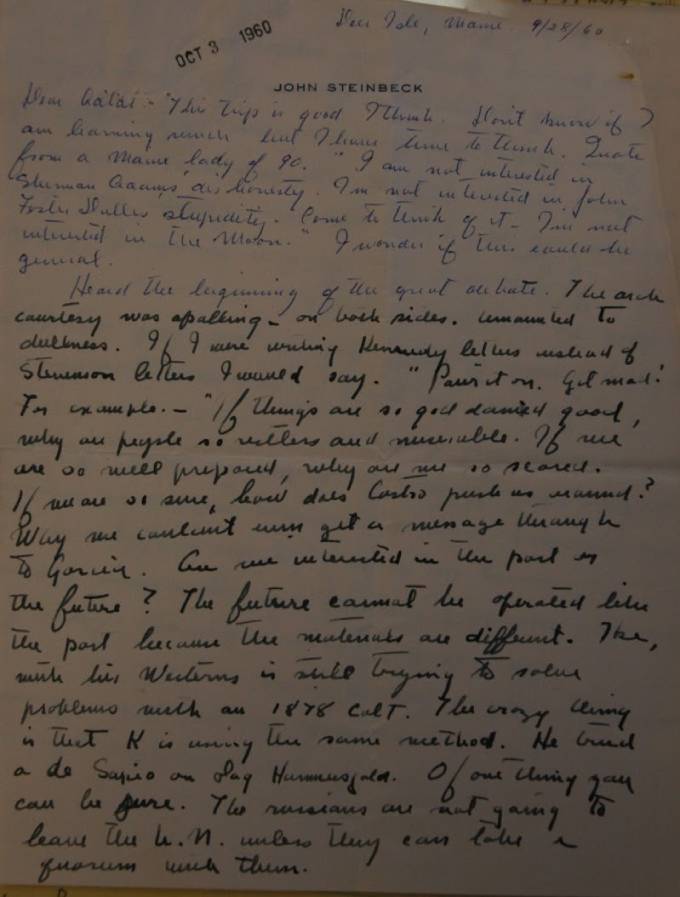

Souder’s commentary on these books, and others, is equally enlightening. Like the attention to movements and events, Souder’s reliance on Steinbeck’s letters and journals rather than literary theory or jargon to explain Steinbeck’s meaning seems perfectly appropriate for a thematic biography like Mad at the World—or The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, which Benson intended as a critical biography, until he realized he had too much material to do both. Reviewers recognized the virtues of this approach in Souder’s book, expressing renewed faith in Steinbeck’s relevance to our time and renewed appreciation for Steinbeck’s courage in confronting the demons faced by a high-functioning neurotic with anger-management issues and fear of success. Steinbeck’s literary reputation needed shoring up, and Benson delivered. Steinbeck’s personal suffering is the greater concern for readers today, and Souder handles the subject with care, charting the dark side of Steinbeck’s empathy and suggesting that, like Jesus, he suffered for our sins more than his own.

Reviewers at major dailies made this point in reviews published during the first half of October. Describing Mad at the World as “smart, soulful and panoramic,” Alexander C. Kafka’s review for the Washington Post heaped praise on Souder for having “chosen a subject on the same continuum” as his two previous books, Under a Wild Sky, his biography of John James Audubon, and his life of Rachel Carson, On a Farther Shore, pointing out that Steinbeck was “another loner who, like Audubon and Carson, refined his craft through mature, dogged, self-punishing industry.” Describing Steinbeck as “one of America’s few bona fide literary celebrities,” Sam Sacks of the Wall Street Journal noted “Two clashing impulses [which] provide the tension in Mr. Souder’s book: Steinbeck’s deep-seated distrust of success and the unyielding creative passion that brought his success about.”

Brenda Wineapple’s New York Times review of October 6 took a similar approach in evaluating Steinbeck’s (and Souder’s) achievement. On thee question of Steinbeck’s quality and character, however, she became a doubting Thomas. Steinbeck “might well be one of those once-popular authors whose names we recognize but whom no one reads beyond junior high. Still, his affecting novels about besieged migrant workers and itinerant day laborers may come back into vogue now that the country, if not the world, faces an economic crisis whose proportions have already been compared to, and may far outdistance, those of the Great Depression.” Unconvinced that suffering equals greatness, Wineapple suggests that “to the reader Steinbeck seems less angry than shy, driven and occasionally cruel — an insecure, talented and largely uninteresting man who blunted those insecurities by writing.” (Non-Times subscribers can read Wineapple’s review at the History News Network.)

Reviewing for the October 9 Boston Globe, Wendy Smith seemed to disagree, describing The Grapes of Wrath as “a lodestar for a new generation of writers seeking to make fiction a vehicle for furious protest and a catalyst for change.” But “Souder’s appreciative yet clear-eyed assessment concludes that Steinbeck’s goal was more modest: ‘He brought people to life who were otherwise invisible and voiceless — because he could, and because he liked them better than the characters who lived in other writers’ work.’” Writing in the October 9 Minneapolis Star Tribune, Mary Ann Gwin praised Souder’s “vivid portrait of a complicated man,” noting that “the best biographers balance empathy for their subjects with an unblinking accounting of their shortcomings” and concluding that “Souder succeeds at this tricky business” in a way that “John Steinbeck, who prized realism above all things, might have approved.”

Most reviewers followed Souder’s lead in evangelizing for Steinbeck. A second exception to the rule was Vivian Gornick, the 85-year-old feminist who reviewed Mad at the World for the October 9 issue of New Republic. Presented as a minority report on Steinbeck by the same left-leaning publication that disparaged him when he was alive and under right-wing attack, Gornick’s diatribe negatively demonstrated the need for Souder’s book: to save Steinbeck’s reputation with readers from political puritanism and neglect. “The amount of print that has been spilled on Steinbeck would fill an ocean,” complained Gornick, a confirmed agnostic on the subject of Steinbeck’s literary divinity: “memoirs, social histories, dissertations, biographies by the yard. Surely by now the cases for and against him as a significant American writer have been sufficiently made.” To the question “Do we need another Steinbeck biography?,” her answer is no.

An anonymous National Book Review post on October 12 rebutted the charge of obsolescence: “Today, the 1962 Nobel Prize winner may be mostly read by high school students, but Souder presents him as a ‘major figure in American literature’ who deserves to be appreciated for his empathy and compassion for the powerless in an inhumane world. Despite his unmistakable admiration, Souder fairly relates Steinbeck’s misogyny, cruelty to his own family, and personal demons of doubt — and the crucially important role his first wife played in his success.” An equally effective counter-argument could be found on the Library of America website a day or two later: “As biographer William Souder shows in his engrossing new book Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck, this long apprenticeship in failure and frustration was the crucible in which Steinbeck’s extraordinary capacity for empathy was forged. Honesty, understanding, and feeling would become the hallmarks of his work, constants even as he experimented with a wide range of forms, styles, and emotional registers. They enabled him, in his greatest work, to give voice to the voiceless, exposing the corrosiveness of power and the perils of social injustice and ecological collapse. At the same time, they did not prevent him from being heedless and sometimes cruel to those closest to him.”

Regional papers also did their part for Steinbeck’s name and Souder’s book. Interviewing Souder for the October 10 St. Paul Pioneer Press, Mary Ann Grossman led with kudos for her fellow Minnesotan. “’Mad at the World’ is the first biography of Steinbeck in 25 years and critics and scholars are loving it,” she wrote. “One of the most enjoyable aspects of William Souder’s biography lies in reading the stories behind the stories,” enthused Hugh Gilmore in the November 18 Chesnut Hill (Pa.) Local: “Souder presents engaging summaries of each book and describes how Steinbeck worked on them, how they were received, and the torments and challenges of their compositions. This is all done with ease and grace and is incorporated into Steinbeck’s life as seamlessly as the stories of his three marriages, two sons, many dogs, raging, dysfunctional family life, and sweet and amusing details.”

Newspapers at both ends of Steinbeck’s America found room for reader responses which, like letters to the editor, veered toward the personal. Woody Woodburn exclaimed in the December 18 Ventura County (Ca.) Star that “biographies do not get any better than Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck.” Reminiscing about Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor in a review for the December 23 East Hampton (N.Y.) Star, Lou Ann Walker recalled that “Years ago on a splendid June afternoon, Elaine Steinbeck invited my husband and me to her Sag Harbor home for tea. Gracious, full of good humor, she took us on a tour of the simple one-story wood-frame house, filled with memorabilia. Her husband had been gone for two decades.” An October 16 post by the poet Stephen Kuusisto at Planet of the Blind said that Souder’s life of Steinbeck is “quite frankly one of the best biographies I’ve read in years, ranking alongside Richard Ellmann’s ‘Oscar Wilde’”—“a nonfiction bildungsroman about a man who was richly alive with all the triumphs and tragedies inherent in a writing life” like Steinbeck’s. “Souder gives us Steinbeck’s blemishes with the light and space to take them in,” wrote Kuusisto. “For my money this is one hell of a compelling book about a writer’s life, the lived life of the unaffiliated places inside.”

Scott Bradfield’s November 28 review for The Spectator was less uncritical. A 65-year-old American who lives and writes in London, Bradfield taught college English and knows his Steinbeck and his literary lives. “William Souder’s Mad at the World is the first significant biography of Steinbeck since Jackson L. Benson’s much longer 1984 volume, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer,” he observed: “It is readable, admiring and compact, and provides a narratively energetic look at a man who suffered many of the same weaknesses as his characters — for booze, benzedrine, depression and bad marriages. But also like his characters, Steinbeck got up every day to test himself all over again, by writing a new book or embarking on a new adventure.” Souder “writes well,” he continued, “and this is a good place to start reading (or rereading) about Steinbeck,” though “Mad at the World sometimes feels a bit too terse and cursory, especially in the last 50 pages, and falls short of communicating a strong sense of the complicated, emotional life of a very complicated, emotional writer.” Bradfield’s example of excessive brevity is the 1944 incident involving Hemingway, O’Hara, and Steinbeck’s walking stick to which Benson devoted two pages and Souder a single sentence. Kuusisto would remind Bradfield that any good bildungsroman, especially that of a figure like Steinbeck, will emphasize the early years, when experience, character, and neurosis are being forged from the materials of daily life.

Looking for Steinbeck’s Ghost

In 1988, Jackson Benson published Looking for Steinbeck’s Ghost, a collection of essays, sketches, and anecdotes about his 15-year struggle to write the 1984 life of John Steinbeck that has become the bible of Steinbeck studies. In it, Benson describes the obstacles to full disclosure put in his path by members of the Steinbeck family and their lawyers, and he admits that childhood is the hardest thing to get right when writing anyone’s biography. The author or editor of books about Hemingway, Benson became John Steinbeck’s official biographer without ever asking for the job. A few years later, Jay Parini—author of a life of Theodore Roethke—received Elaine Steinbeck’s approval and help in writing the second “authorized” life of her husband. Forty years after Benson, and 25 years after Parini, William Souder had the benefit of their labor, along with the pioneering work of Richard Astro (on Steinbeck and Ricketts), Robert DeMott (on Steinbeck’s reading and journal-writing), and Susan Shillinglaw (on Carol Henning and her marriage to John Steinbeck). By 2016, when Souder started his research on Steinbeck’s life, Steinbeck’s widow, sons, and sisters were gone. This was a lucky break for someone who came to biography from the newsroom, where the truth is everything, and from writing critically acclaimed lives of two Americans—Carson and Audubon—who achieved greatness in fields where truth always trumps fiction.

A Bible reader since Sunday school in Salinas, Steinbeck was attracted to the author of the fourth gospel for literary reasons. Like a good novelist, St. John balances description with dialogue in his gospel, and he starts with an idea about his subject—Jesus is Christ—that guides the narrative, coloring its language and guiding the selection of events to prove its point. Compelled by what Souder characterizes as a pathological urge for privacy, Steinbeck would have preferred the anonymity of the biblical John, whose origin and identity are unknown. John’s alternate version of Jesus’s birth, ministry, and death appealed to Steinbeck; when he was 60 and world-famous, John’s gospel inspired the language of his 1962 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, just as it did the title of the spurious pamphlet about Steinbeck’s righteous wrath at the age 18, published by a friend when Steinbeck was under attack for writing social-protest fiction in 1939.

It’s unclear that St. John read Mark or the others before writing his own gospel. But it’s certain he was writing for a different audience—a contemporary audience with different concerns—just as William Souder has done in writing the life of Steinbeck for a new generation of readers unfamiliar with Benson and unlikely to pick up The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer. We still revere Mark even if, like Steinbeck, we prefer John’s prose style and plot line. If early reviews of Mad at the World are predictive, Souder’s life won’t replace Benson’s on the shelf of essential books about Steinbeck. But Benson will have to move over, as he modestly predicted in 1988, in Looking for Steinbeck’s Ghost: “I had to force myself to realize that there would be many biographies of John Steinbeck and that my work would ultimately be only part of a process. There would be biographers after me who would use what I had discovered, add material of their own, and, indeed, find mistakes or omissions in my account, and they would come up with different, perhaps even more perceptive and valid, accounts of the life and work than mine.”

Photograph of William Souder, with Sasha, by Liz Souder.