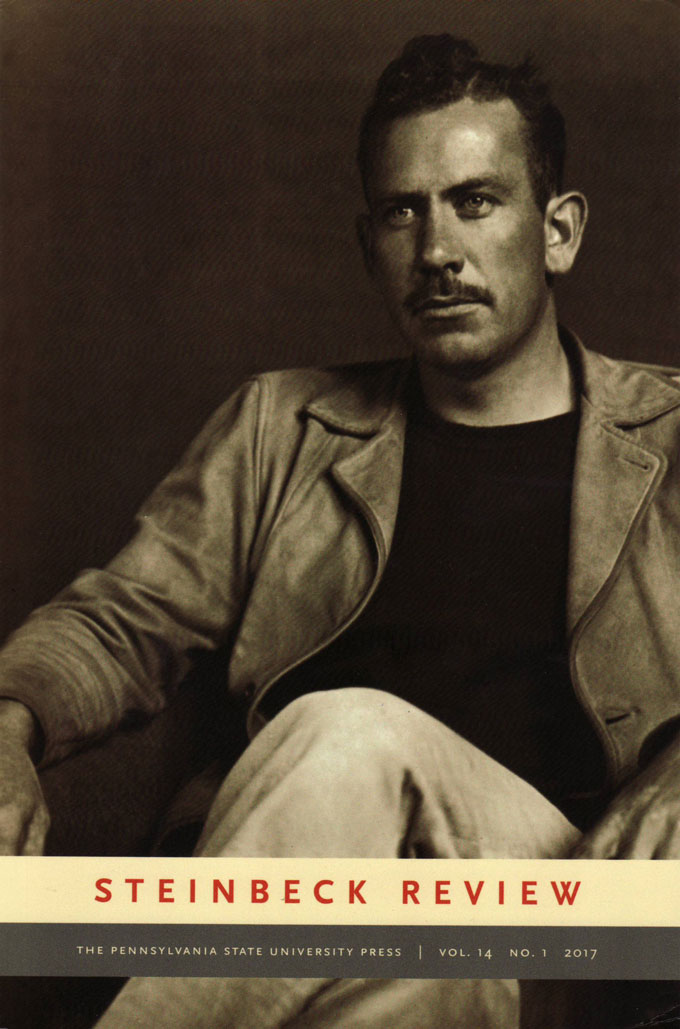

Steinbeck Review, recently honored by listing in the international database Scopus, has expanded its purpose to specify that articles submitted for publication not only delight and instruct (à la Horace), but also illuminate issues, including the themes and problems treated in John Steinbeck’s work. This policy change reflects Steinbeck’s concern for truth and enlightenment, as well as for compassion and magnanimity, in books that warned readers of moral decline—and potential demise—in the America that Steinbeck loved. The subject of America and Americans preoccupied the writing of his final decade, and The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel, acknowledged this didactic purpose: “Readers seeking to identify the fictional people and places here described would do better to inspect their own communities and search their own hearts, for this book is about a large part of America today.”

How to Submit Papers for the Spring 2018 Issue

In addition to more traditional scholarly articles, Steinbeck Review invites the submission of papers for the Spring 2018 issue that reflect John Steinbeck’s continued relevance for our time. All critical and theoretical approaches are welcome, as are essays focused on women’s and gender studies, rhetorical concerns, ecology and the environment, international appeal, and comparative studies. Poetry submitted for publication should deal with themes or places associated with Steinbeck’s life and work. Submit papers before January 15, 2018 through the journal’s automated online submission and peer review system at the Pennsylvania State University Press.