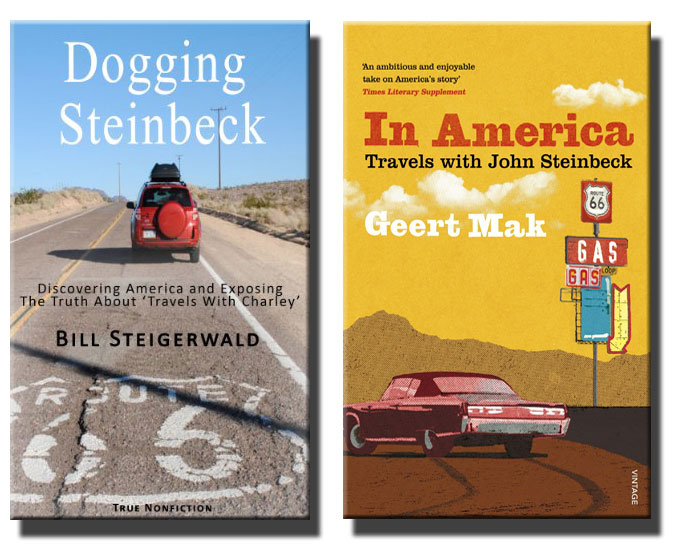

Bill Steigerwald (at left), the American journalist who wrote Dogging Steinbeck “to expose the truth about Travels with Charley,” accepted the invitation to address an audience in Holland that included Queen Máxima (right) when his friend Geert Mak (center), the Dutch journalist who wrote In America—Travels with John Steinbeck, was awarded the 2017 Prince Bernhard Cultural Prize. “My appearance at the ceremony for Geert Mak on November 27 in Amsterdam was a total surprise to Mak,” says Steigerwald. “It was like the old time TV show This is Your Life.” The text of the tribute to a friendship that started with Steinbeck is published here for the first time.—Ed.

Good afternoon. Thank you for inviting me.

Though Geert and I were born an ocean apart, and though he’s much smarter and far more accomplished than I’ll ever be, we have some things in common.

We’re both 70-year-old Baby Boomers.

We both started out life with lots of hair.

We both grew up to be journalists and writers.

And we both specialized in the kind of drive-by journalism that he used so masterfully in 2010 for what became his American history book, In America—Travels With John Steinbeck.

In America is a great mix of big-picture history, on-the-road journalism and progressive opinion. The Guardian newspaper called it “witty, personable and knowing”—and it is.

But perhaps the most impressive thing about it is that it reads like it was written by a lifelong American, not a longtime citizen of Europe.

As a way to show how big America is and how much it had changed in the previous 50 years, Geert came up with idea to follow the same route around the United States that John Steinbeck took in 1960 for his famous road book Travels with Charley.

It was a really good idea—and I had thought of it too.

That’s why early on the morning of September 23, 2010, exactly 50 years after Steinbeck left on his iconic 10,000-mile road trip, Geert and I each drove to the great novelist’s former house on Long Island, New York.

We didn’t bump into each other at Steinbeck’s place.

I left to catch the ferry to New England an hour or so before Geert and his wife Mietsie arrived in their rented Jeep Liberty.

For nearly two months, from Maine to California and down to New Orleans, the Maks and I traveled to the same places and even interviewed some of the same people.

For the record, as we journalists like to say, the Maks traveled like adults. They stayed in motels and drove responsibly.

I drove alone, as fast as a runaway teenager, often sleeping in my Toyota RAV4 in Walmart parking lots or beside the highway.

We never did meet on the road, but before Geert got out of New England he discovered that I was a day or so ahead of him.

He also saw I was posting a daily road blog on a newspaper website and slowly proving my case that Steinbeck had fictionalized large chunks of what was supposed to be a nonfiction travel book.

Geert, who already had his own suspicions about Steinbeck stretching the truth, realized he had to include me in his book.

Two years later, after a Dutch reader alerted me that my name was in In America, Geert and I were exchanging friendly transatlantic emails–in English.

We compared notes on Steinbeck and the road trip we shared.

I confessed to him that I was a lifelong libertarian, someone he’d call “a radical individualist.”

He confessed to me that he was “a typical latte-drinking, Citroën-driving, half-socialist European journalist and historian.”

Someday, we promised each other, we would meet in Holland over a Heineken and have a friendly debate about the two very different 2010 Americas we found along the same stretch of highway.

I never made it to Amsterdam–until now.

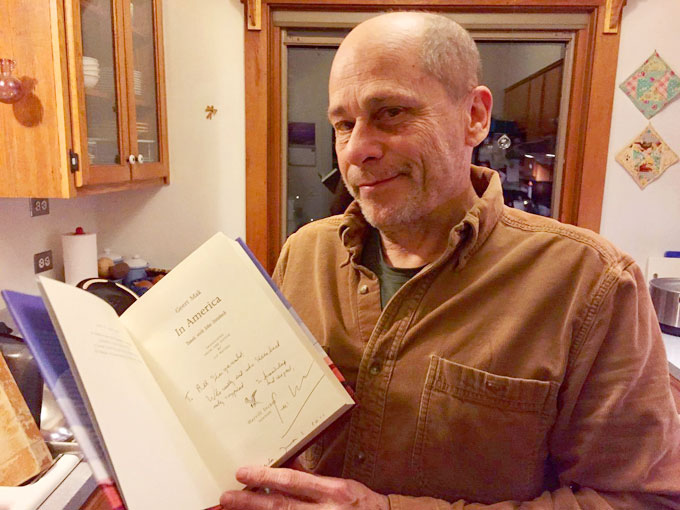

But in May of 2014, when Geert was in New York at a writers conference, he jumped on a plane and flew to Pittsburgh for three hours just to meet me and buy me lunch.

His visit was both an honor and a special treat.

He was even nicer in person than he was online. In addition to being a renowned European journalist and historian, he was clearly a great guy, a regular guy.

That’s a high compliment from an American, but I don’t think that’s news to many people in the Netherlands.

Hello, Geert. I’m a little bit over-dressed. But I’m here to buy you that beer.