Monterey County’s move to rename Confederate Corners, the isolated intersection south of Salinas, California restyled as Rebel Corners in The Wayward Bus, has renewed interest in John Steinbeck’s 1947 re-imagining of Plato’s Ship of Fools allegory, from Book VI of The Republic. Located on Highway 68 in unincorporated Monterey County, Confederate Corners got its name during the Civil War, when a handful of Southern sympathizers proposed seceding from California as a mark of solidarity with the Confederate States of America. Except for informed readers of The Wayward Bus, the Monterey County ranchers’ mini-rebellion was largely forgotten until controversy over the removal of racist flags and statues in several states of the former Confederacy erupted, post-Charlottesville, into Trumpian rhetoric around issues of ethnicity, immigration, and loyalty to the flag. Like the Ship of Fools metaphor embedded in Steinbeck’s neglected novel—which few critics recognized, then or now—the recent news from Monterey County is replete with the kind of irony that appealed to the author, a big-tent American who began writing The Wayward Bus in and about Mexico.

Archives for October 2017

John Steinbeck’s Warning in Playboy about Donald Trump

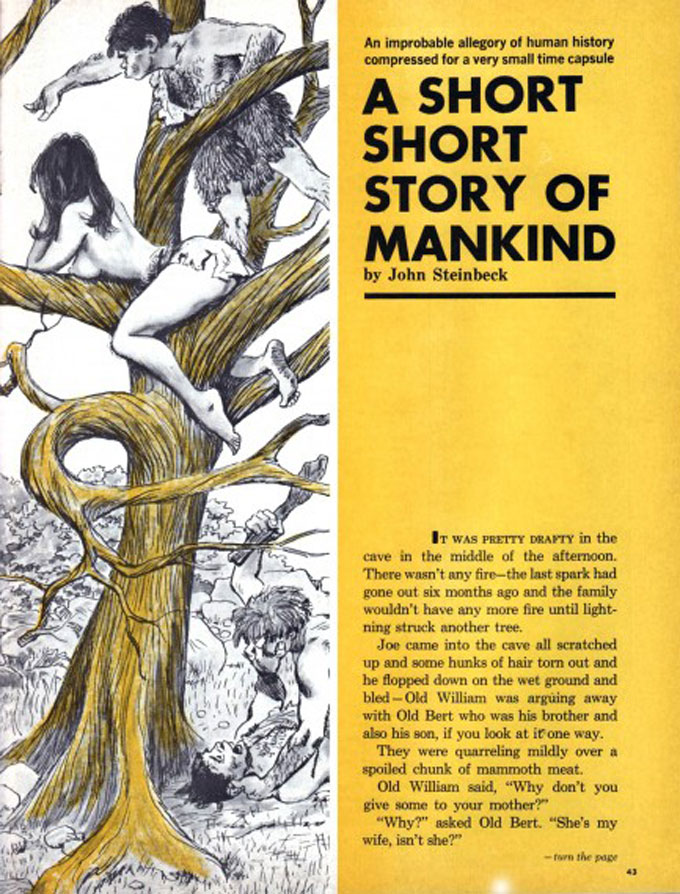

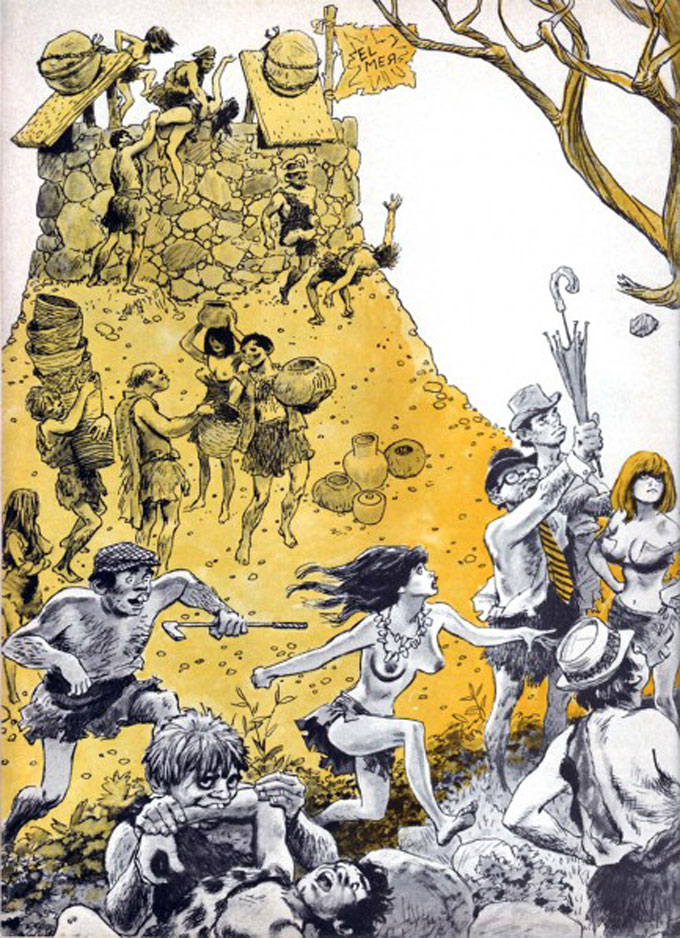

The long relationship between Playboy magazine and Donald Trump, America’s playboy-in-chief, is old news. But the recent death of Hugh Hefner unearthed some surprising Playboy connections, including a list of major authors—among them John Steinbeck—who wrote for the serious men’s magazine that paid well and reached readers otherwise untouched by serious literature. In light of our president’s tweets and threats to bomb America’s enemies back to the Stone Age, Steinbeck’s satirical “Short Short Story of Mankind,” first published in the April 1957 issue of Playboy, has a message as relevant today as it was 60 years ago, when the golf-loving Dwight Eisenhower was president and the Cold War was on in earnest.

An allegory in the style of Mark Twain, Steinbeck’s account of human progress from savagery to civilization has a cartoon quality picked up by the illustrator for Adam, which republished Steinbeck’s Playboy piece in 1966 (images above and below). But like the “poisoned cream puff” of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row fiction, the mirth of “A Short Short Story of Mankind” is meant to be sobering. At every step, Steinbeck suggests, our progress as a species has faced resistance from a constant and terrifying tribal stupidity which, unchallenged, would lead to our extinction. “It’d be kind of silly if we killed our selves off after all this time,” he concludes. “If we do, we’re stupider than the cave people and I don’t think we are. I think we’re just exactly as stupid and that’s pretty bright in the long run.”

To my knowledge “A Short Short Story of Mankind” has never been anthologized, but it’s time it was. Living in the daily shadow of Donald Trump’s presidency, we need its dark warning and its ray of hope, the somber and uplifting counterpoint that echoes Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech and later writing. Today, six decades after Playboy magazine published John Steinbeck for the first and only time, it’s useful to remember that the author died a month after the election of Richard Nixon, whose dishonesty and demagoguery he deeply distrusted. It’s easy enough to imagine what he’d have to say about Donald Trump if he were still alive. The warning he’d have for a nation under Trump is implicit in the imagery and tone of his Cold War admonition to America under Eisenhower—an incurious president who also preferred golf but, unlike Trump, read the occasional book and avoided Stone Age rhetoric. Read the piece and judge for yourself.

New Yorker Says French Editor Uses American Literature, Travels with Charley to Explain America

The October 16 issue of New Yorker magazine reminds Steinbeck fans of their favorite author’s continued usefulness in understanding America and Americans. In a Talk of the Town item titled “Paris Postcard: In Search of America,” Lauren Collins reports that Francois Busnel, the host of a popular French television show about literature, is the new editor-in-chief of America, a French magazine “conceived to help French readers make sense of its namesake in the age of Trump.” Not surprisingly, Busnel looks to American literature to help explain Trump to his fellow countrymen. “We’re living in a profoundly novelistic era,” Busnel says, adding that Travels with Charley remains his favorite book about America and Americans in any age.

Steinbeck Review Expands Scope, Issues Call for Papers

Steinbeck Review, recently honored by listing in the international database Scopus, has expanded its purpose to specify that articles submitted for publication not only delight and instruct (à la Horace), but also illuminate issues, including the themes and problems treated in John Steinbeck’s work. This policy change reflects Steinbeck’s concern for truth and enlightenment, as well as for compassion and magnanimity, in books that warned readers of moral decline—and potential demise—in the America that Steinbeck loved. The subject of America and Americans preoccupied the writing of his final decade, and The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel, acknowledged this didactic purpose: “Readers seeking to identify the fictional people and places here described would do better to inspect their own communities and search their own hearts, for this book is about a large part of America today.”

How to Submit Papers for the Spring 2018 Issue

In addition to more traditional scholarly articles, Steinbeck Review invites the submission of papers for the Spring 2018 issue that reflect John Steinbeck’s continued relevance for our time. All critical and theoretical approaches are welcome, as are essays focused on women’s and gender studies, rhetorical concerns, ecology and the environment, international appeal, and comparative studies. Poetry submitted for publication should deal with themes or places associated with Steinbeck’s life and work. Submit papers before January 15, 2018 through the journal’s automated online submission and peer review system at the Pennsylvania State University Press.

How John Steinbeck’s Name Caused Confusion at the Pacific Grove Post Office

Just the other day she stepped into our Pacific Grove, California gallery with a distinguished-looking gentleman who likes to do carvings. Her name’s Joy and the gentleman was her husband Jerry.

The subject of John Steinbeck came up—as it usually does in the gallery—and Joy said:

“My parents couldn’t stand him.”

“Why not?”

“They’d get late night phone calls from people, usually inebriated, asking for him—for John Steinbeck. Getting them up in the middle of the night infuriated my folks.”

Steinbeck probably would have liked Joy, a school teacher and administrator who has taught and teaches everything from English and business to quilting, because she added with finality: “And that’s all I know about it.”

It reminded me of something Ma Joad might say.

I waited a bit then asked some questions anyway.

Joy said her parents came to Pacific Grove in 1943. Her father was about 37 years old at the time but could have been drafted into the army even though he and his wife Lela had a young child. Someone recommended that he join the post office instead of the army and he did, becoming, eventually, a clerk in the Pacific Grove branch on Lighthouse Avenue, a branch Steinbeck would have used for many of his postal needs in the 1930s—perhaps sending off typescript copies of Tortilla Flat and Of Mice and Men to his publisher in New York.

What, I asked Joy, was her parents’ last name?

“Steinecke,” she said. “It came right after Steinbeck in the phone book.”

“And what was your father’s first name?’

“John,” she said.

It was beginning to come together . . . .

I could see someone in a phone booth looking up the Steinbeck phone number in the middle of the night—maybe to give the author some good advice, not realizing he was now living on the East Coast. Having had a few drinks, the caller could easily morph Steinbeck into Steinecke, or maybe the finger marking the place slipped down the page just a smidge and, hey, it still says John! If the Steinbeck name wasn’t listed, Steinecke would do nicely.

As a result, Mr. Steinecke, scheduled to begin work at the post office in a few hours, gets calls at two, three in the morning. Not easy to get back to sleep, the phone conversations likely still echoing in his head:

“Mr. Steinbeck, I think . . . I think you should change the ending of Tortilla Flat.“

“I’m a postal clerk!”

“I know, but you wrote the book.”

According to Joy, John Steinecke would not have been amused.

“My dad was the grandson of a Prussian general who immigrated from Germany in the mid-1800s,” Joy said. “His sense of humor was not particularly well-developed, and he would probably huff about those phone calls if he were still alive. Anyway, he might not laugh, but he definitely would be pleased that you were writing about him and John Steinbeck.”

So, on a recent morning, with images of John Steinbeck and John Steinecke dancing interchangeably in my head, I went into the Pacific Grove post office for stamps and spoke with a clerk named Ron. For all I know, Ron was standing where Mr. Steinecke stood decades ago.

Ron said, quite the opposite of what Mr. Steinecke thought in the 1940s, “Steinbeck’s one of my favorites. People recommend other writers, but I always seem to come back to Steinbeck.”

Of course, if Ron had been living back then, working in the Pacific Grove post office, and his name was John Steinecke, even Ron Steinecke, he might have switched his literary allegiance to Hemingway or Faulkner.

Period photo of John Steinecke serving young customers at the Pacific Grove post office from Norton and Gus, by Margaret Hayden Rector (Grossmont Press, 1976).

The Passing of Frank Wright And the Men’s Clubs of John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row

The recent death of Monterey, California businessman Frank Wright at age 98 served as a reminder that the life of Doc’s Lab—Ed Ricketts’s marine biology laboratory on Cannery Row—had two distinct phases. The 1930s and 1940s were the period of John Steinbeck and Ricketts and the artists and poets and philosophers who gathered around them. The 1950s began the Lab’s second incarnation as a men’s club of painters, cartoonists, teachers, journalists, lawyers, and business people founded by Frank and his friends—all with a passionate interest in Steinbeck and Ricketts and a way of life that was already fading into the past. Like the earlier, even more casual men’s club, Frank’s group met and socialized and partied in the Lab’s raffish rooms and outdoor concrete deck and holding tanks overlooking Monterey Bay. In the process they kept the Lab largely as it was, preserving it for posterity.

The Men’s Club That Saved Doc’s Lab

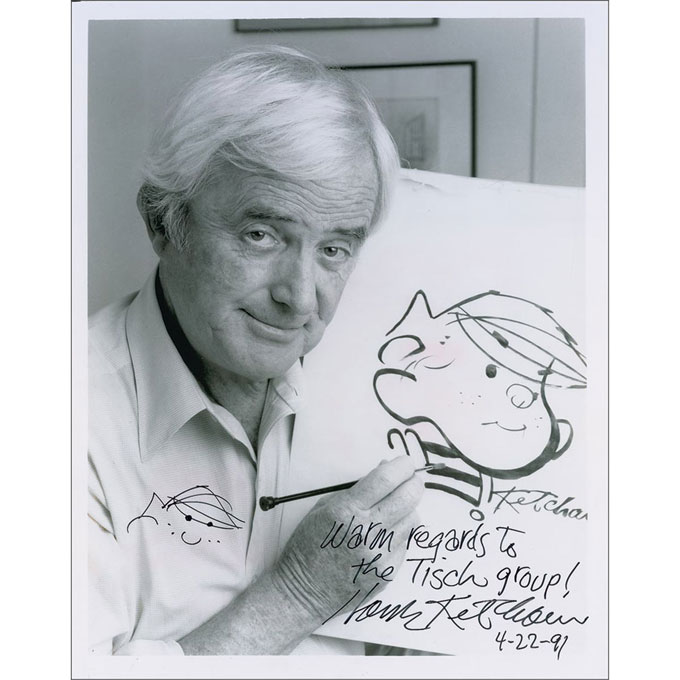

Frank met Ricketts after joining the Army in 1942, and they remained close until Ed died. In the early 1950s, Frank and two other men bought the Lab as a meeting place for their circle of artists, educators, and fellow enthusiasts. For a slim sampling of this second generation Cannery Row men’s club, there was Gus Arriola, the brilliant creator of the comic strip Gordo. Eldon Dedini, the farm boy from South Monterey County who became a successful and sophisticated cartoonist for Esquire and Playboy. Morgan Stock, the teacher and director who spearheaded the drama department at Monterey Peninsula College, which in turn named a theater for him. The irrepressible, crusading attorney Bill Stewart. The Dennis the Menace cartoon creator Hank Ketcham (in photo), also a serious painter. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts, they were creative types drawn together by a love of talk, drink, and music. The Monterey Jazz Festival grew from their collaboration. So did the idea of making Doc’s Lab a living museum, now under management by Monterey, California’s department of cultural affairs.

The End of an Era on Cannery Row

A personal memory: Years ago my late wife Nancy and I were walking along Cannery Row with Sue and E.J. Eckert (in photo to Nancy’s right). When we stopped in front of the Lab we got lucky. Frank Wright was standing on the stairs with Dennis Copeland, cultural affairs director for Monterey, California. Frank offered to give us a tour. He was a natural storyteller, warm and personable and charming, and when we left, walking out onto the bright morning sunlight of Cannery Row, the Eckerts said, “Boy, that was something!” They’ve never forgotten the experience. It was Frank’s gift to many when he was alive, and he was active well into his 90s. His death was indeed the end of an era.

Photo of Frank Wright courtesy Monterey County Weekly.