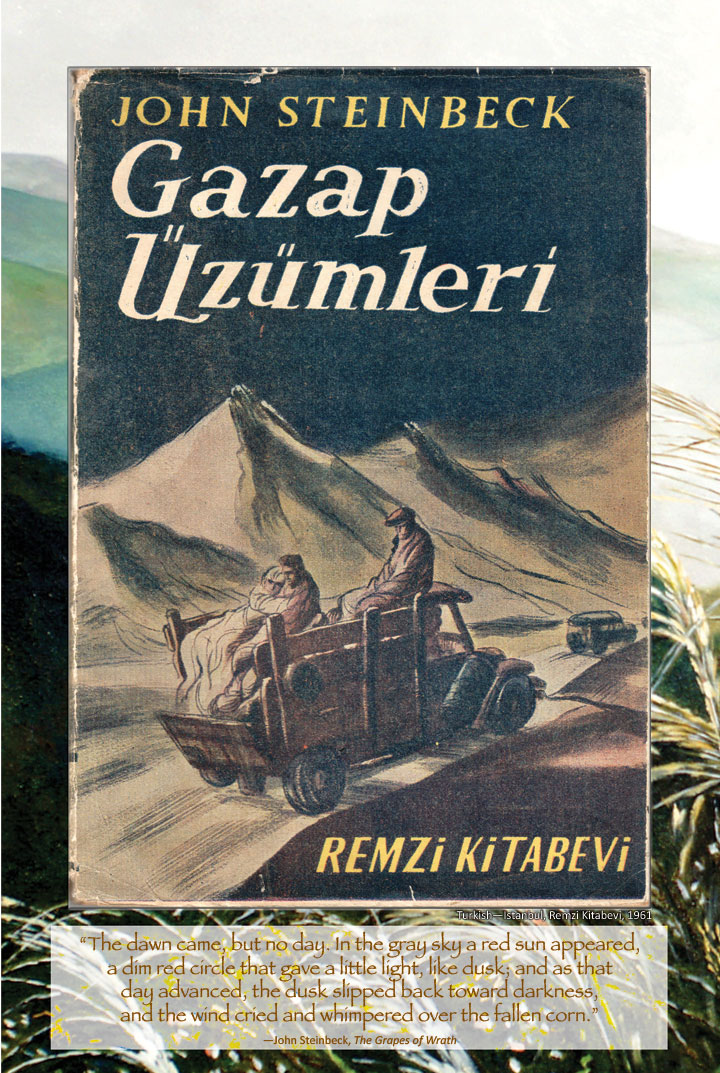

Shortly after emigrating to America in 1939 with the poet W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, the British author of Berlin Stories, wrote a review of The Grapes of Wrath for Kenyon Review, the new American literary magazine that—like John Steinbeck—quickly gained prestige and influence with readers and critics in the United States. Intimate friends since school days in England, Isherwood and Auden arrived in New York in January. Isherwood moved on to California, and in July confided this to his diary: “I forced myself to write—a review of The Grapes of Wrath and a short story called “I Am Waiting”—but there was no satisfaction in it.” Despite his mood, Isherwood’s review of The Grapes of Wrath was upbeat and positive; like the diaries, novels, and plays that he produced over five decades in America, his insights (and criticism) seem as fresh today as they were in 1939. What made Christopher Isherwood, an adoptive American, so receptive to John Steinbeck’s all-American novel when it was published? Temperamentally and socially the two men were opposites. Steinbeck preferred privacy and solitude to self-confession and self-promotion, the distinguishing features of Isherwood’s career as the main character in his books. Steinbeck’s people were middle-class, immigrant, and self-made; Isherwood came from landed gentry with deep roots in English history. But both men believed in the power of sympathy and synchronicity, and coincidence can be as important as difference in life, as in literature.

John Steinbeck, Christopher Isherwood, and Synchronicity

Both writers were born in the decade prior to World War I, when America—like England—was outgrowing Victorianism. Both were christened (and later confirmed) into the Anglican Church, an experience that effected their prose style, if not their souls. Each was an elder or only son in a family dominated by an ambitious mother: Isherwood’s father was a British infantry officer who was killed at Ypres in 1915, leaving behind a wife and two sons, an older brother who inherited the Isherwood fortune, and three younger siblings with Steinbeckian names—John, Esther, and Mary. From childhood, John Steinbeck and Christopher Isherwood were imaginative storytellers with a drive to write that drove them to drop out of college to follow their muse. By 1940 both had achieved success in their calling and hobnobbing with film-world celebrities and hangers-on in Hollywood. Despite holding opposite views about the value of autobiography, both worked well in various forms, writing novels, play-novelettes, travel books, and war correspondence that attracted a following. Each loved the warmth of the sun and the sound of the sea—unlike W.H. Auden, who stayed behind in New York in 1939 when Isherwood left for Los Angeles, where Isherwood remained until he died in 1986. (He became an American citizen in 1946.) Oddly, though Hollywood was a village and they had mutual friends in the business, neither Isherwood’s dairies not Steinbeck’s biographers suggest that they ever met.

W.H. Auden and His Kind Weren’t John Steinbeck’s

Nature and nurture conspired to keep them apart. Like other members of W.H. Auden’s circle, Isherwood was openly gay from an early age. Steinbeck grew up in small-town Salinas, where deviance was closeted; the Isherwoods were cosmopolitan provincials with property in London (Isherwood’s Uncle Henry was homosexual, and a jurist ancestor signed King Charles’s death warrant). Unlike Steinbeck, who struggled at the start and stayed in America until established, Isherwood inherited position, connections, and cash that helped pave his way, traveling extensively in Europe before settling in America. His exploration of Berlin’s pre-Nazi gay underground provided material for the 1930s Berlin fiction later adapted for stage and screen as Cabaret. His early novels—All the Conspirators (1928), The Memorial (1932), Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1935)—sold better than Steinbeck’s books—Cup of Gold, The Pastures of Heaven, To a God Unknown—published in the same period. Above all, his relationships with other writers differed dramatically from those of Steinbeck. Isherwood was a born extrovert who wrote poetry and plays with W.H. Auden and nourished friendships with other famous authors, including Aldous Huxley and Thomas Mann. Steinbeck took a disliking to Alfred Hitchcock, the quintessentially English snob who directed the war movie (Lifeboat) scripted by Steinbeck. Isherwood’s collaboration with the Austrian director Berthold Viertel was so gratifying that he wrote a novel (Prater Violet) about their friendship.

A Neglected Grapes of Wrath Review, Still Relevant Today

Christopher Isherwood had a reputation as a ready reviewer when he arrived in America with W.H. Auden, so the Grapes of Wrath assignment made sense. Although the piece he produced for The Kenyon Review is mentioned in John Steinbeck: The Contemporary Reviews (Cambridge University Press, 1996), that helpful anthology omits the full text, which seems a shame. Fortunately, it can be found in Exhumations (Simon and Schuster, 1966), a collection of Isherwood’s stories, articles, and verse that also includes reviews of authors (Stevenson, Wells, T.E. Lawrence) of interest to Steinbeck and Isherwood, two writers with more in common than their differences suggest. Here are four samples, still relevant, from the 1939 review of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath:

(1) On the Promise of Steinbeck’s California

“Meanwhile, the sharecroppers have to leave the Dust Bowl. They enter another great American cycle—the cycle of migration towards the West. They become actors in the classic tragedy of California. For Eldorado is tragic, like Palestine, like every other promised land.”

(2) On Participating in Steinbeck’s Story

“It is a mark of the greatest poets, novelists and dramatists that they all demand a high degree of co-operation from their audience. The form may be simple, and the language as plain as daylight, but the inner meaning, the latent content of a masterpiece, will not be perceived without a certain imaginative and emotional effort. . . . The novelist of genius, by presenting the particular instance, indicates the general truth [but] the final verdict, the ultimate synthesis, must be left to the reader; and each reader will modify it according to his needs. The aggregate of all these individual syntheses is the measure of the impact of a work of art upon the world.”

(3) On Didacticism in Fiction

“Mr. Steinbeck, in his eagerness for the cause of the sharecroppers and his indignation against the wrongs they suffer, has been guilty, throughout this book, of such personal, schoolmasterish intrusions upon the reader. Too often we feel him at our elbow, explaining, interpreting, interfering with our independent impressions. And there are moments at which Ma Joad and Casy—otherwise such substantial figures—seem to fade into mere mouthpieces, as the author’s voice comes through, like the other voice on the radio.”

(4) On Art vs. Life in Novels

“If you claim that your characters’ misfortunes are due to the existing system, the reader may retort that they are actually brought about by the author himself. Legally speaking, it was Mr. Steinbeck who murdered Casy and killed Grampa and Granma Joad. In other words, fiction is fiction. Its truths are parallel to, but not identical with, the truths of the real world.”