Brooklyn Cab Ride

Did the Turk wearing Levis and a Knicks hoodie

think he needed to proclaim he was a secular Muslim

after the religiously motivated murders of the cartoonists

at Charlie Hebdo in Paris? Did he imagine his applause

for freedom of speech was anything but its own gratuity?

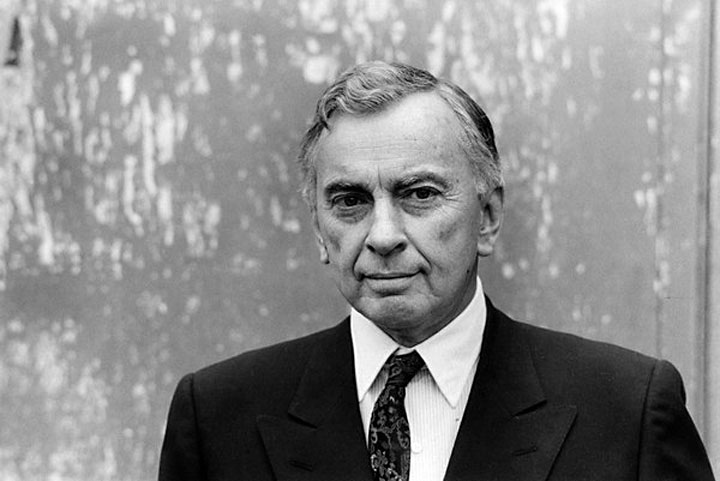

The driver could have been John Steinbeck’s doppelganger.

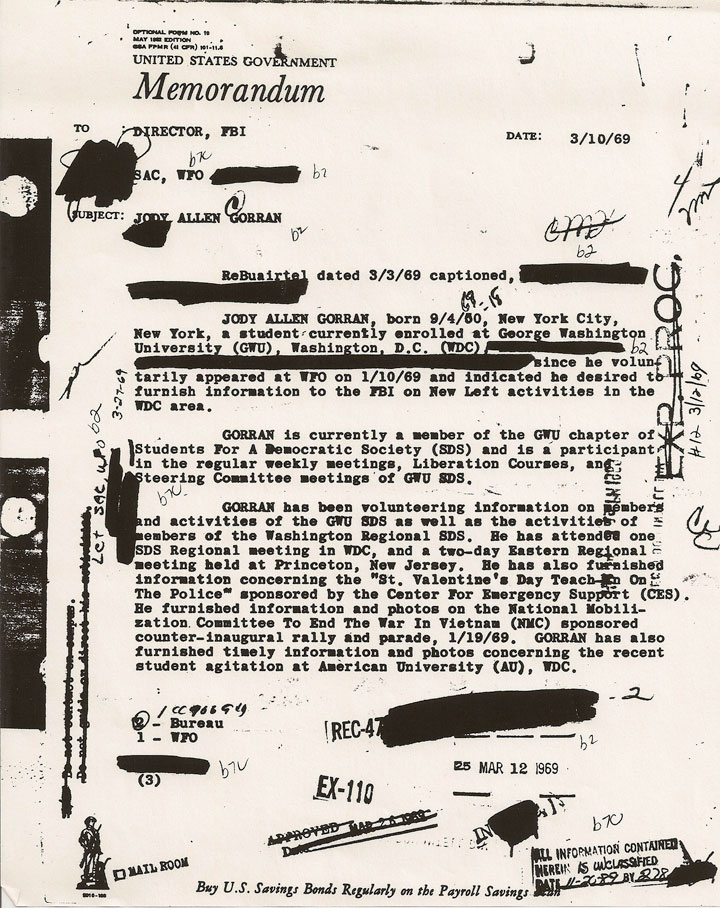

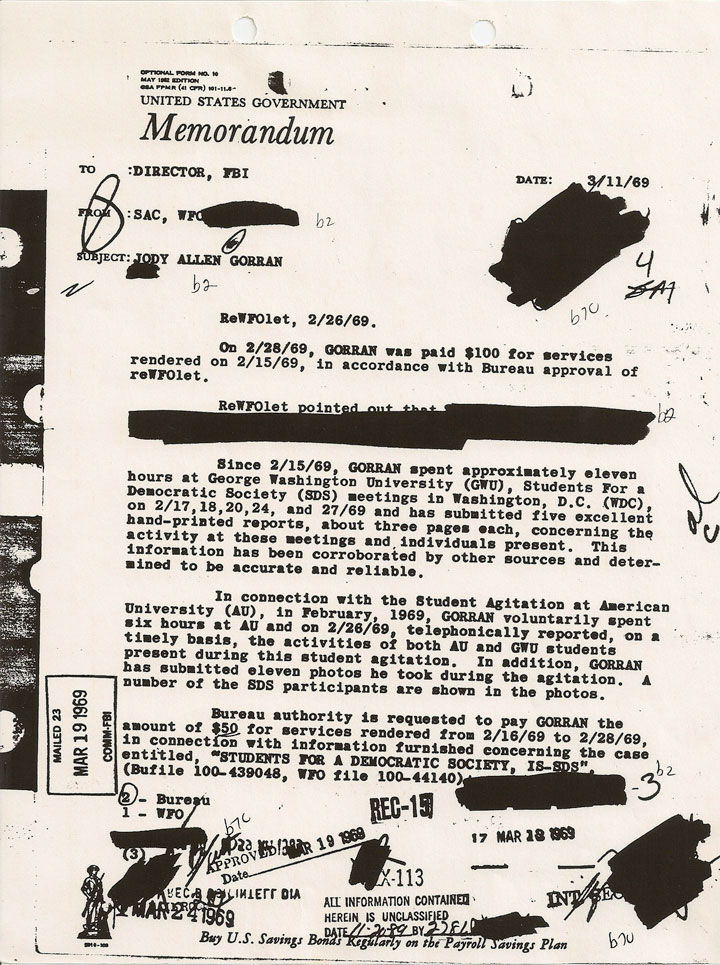

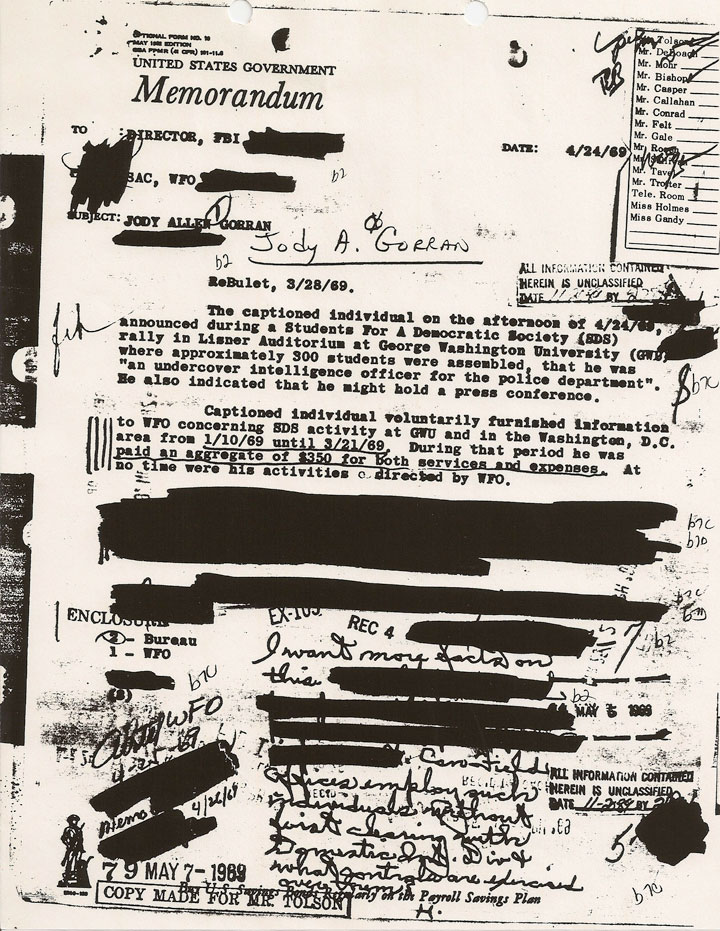

Hair and face and age were that close. John Steinbeck who

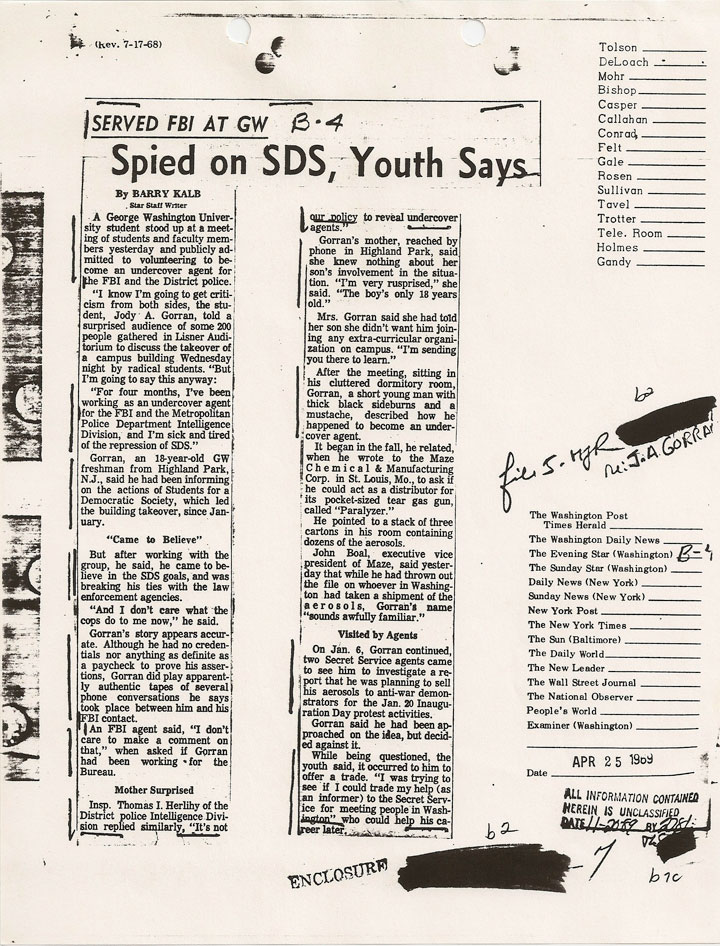

died in New York in ’68 with a fat FBI file for speaking out,

for believing that what we write and say matters. That day,

January in the streets like any lucky stiff from New Jersey,

the Turk in an NBA hoodie said the Prophet Muhammad

was a camel driver who married once when the world

has a polygamous heart. Was that blasphemy or was

the driver’s impertinence the sort of thing that a man

of a certain age will say to feel good about himself?

He wasn’t saying there isn’t a God. He was saying

that being alive and American isn’t easy. Idling

on Smith and Pacific, maybe The One God

was in the rippling reverberations before we

said what we said over the blare of car horns.