The 75th anniversary of the publication of The Grapes of Wrath will be celebrated in a public organ concert beginning at 7:00 p.m. on August 22 at California’s Carmel mission. Inspired by The Grapes of Wrath, Tortilla Flat, Sea of Cortez, and John Steinbeck’s admiration for the music of J.S. Bach, the literary-minded program will be performed by James Welch, California’s foremost concert organist and a fan of John Steinbeck’s fiction.

The historic Carmel mission is located at 3080 Rio Road in Carmel-by-the-Sea, several miles south of Monterey and Pacific Grove. Along with inland Salinas, the three Monterey County communities were inhabited or frequented by Steinbeck during his formative California period and appear frequently in his writing. The 1935 novel Tortilla Flat is set in Monterey, the site of Cannery Row and the launching point of Steinbeck’s 1940 Sea of Cortez expedition with his close friend Ed Ricketts, the marine biologist, to study the coastal ecology and culture of Baja California. The result of their legendary trip and writing collaboration was Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research (1941), the book that distilled the ideas animating The Grapes of Wrath, In Dubious Battle, and Of Mice and Men, Steinbeck’s labor trilogy of the late 1930s.

A native of Southern California who started college as a pre-med student, James Welch earned a doctorate in organ performance from Stanford University and lives in Palo Alto, where he has held the post of organist at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church since 1993. A member of the music department at Santa Clara University and a former faculty member at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he has researched and recorded Latin American organ music on a Fulbright grant, performed music by European and American masters at cathedrals and concert halls throughout the world, and recorded works by a variety of composers for the organ, including the four featured on his August 22 concert at Carmel Mission. (Welch will perform a program of music by British composers on the famed organ of the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City on August 3.)

Music for Steinbeck from J.S. Bach to “Night in Monterey”

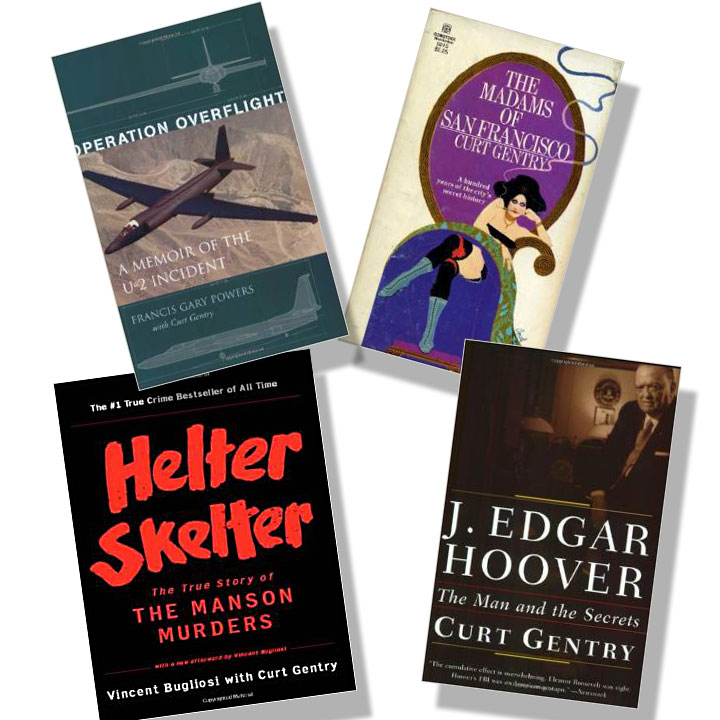

Welch’s Carmel mission concert will open with J.S. Bach’s mighty Toccata in C major and other selections by the composer whom Steinbeck and Ricketts described in Sea of Cortez as “breaking through” to a state of mystical sublimity in sound. It will continue with Steinbeck Suite, a five-movement work written by Franklin D. Ashdown in honor of the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath and inspired by scenes from Tortilla Flat and from Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. Ashdown, who lives in New Mexico, is one of America’s most widely published living composers of music for organ and choir. Steinbeck Suite was premiered by Welch at the Santa Clara mission on February 17 and will be published in 2014 by Zimbel Press, a respected publisher of new music. Ashdown visited the Carmel mission following the Santa Clara premiere and played its pipe organ.

Also featured on Welch’s Carmel mission program will be a pair of 20th century California composers who were inspired by the Monterey Peninsula and San Francisco Bay Area in their musical writing. Richard Purvis (1913-1994), the organist and choirmaster of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco following World War II, enjoyed camping on the Monterey coast, a passion colorfully reflected in Nocturne (“Night in Monterey”), one of several Purvis pieces that will be performed by Welch, who published a biography of Purvis in 2013. Dale Wood (1934-2003), the organist and choirmaster at San Francisco’s Episcopal Church of St. Mary the Virgin in the 1970s, wrote music with a distinctively California style influenced by musical forms familiar to Steinbeck, including jazz, gospel music, and the music J.S. Bach. Welch’s Carmel mission concert will include Wood’s brilliant setting of the chorale “That Easter Day With Joy Was Bright” in celebration of the seminal Easter Sunday chapter from Sea of Cortez.

Carmel Mission and Steinbeck’s Feeling for Catholicism

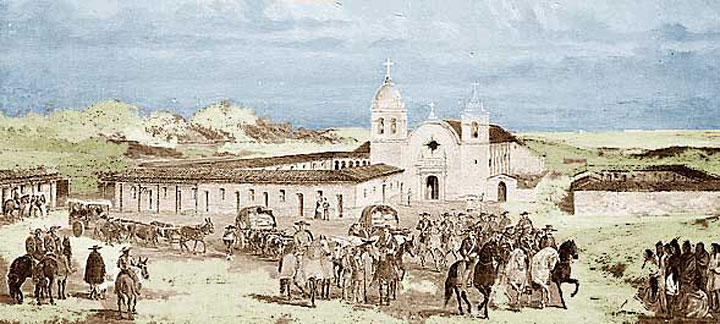

San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission was the second California mission built under the administration of Junipero Serra, the Franciscan missionary who made the Carmel mission his headquarters from 1770 until his death in 1784. Like other California missions, it fell into disuse and decay following secularization by the Mexican government in the 19th century. By Steinbeck and Ricketts’s time, the restoration advocated by Steinbeck and others was underway, and the Carmel mission became a parish church in 1932—the original goal of the Franciscans for the missions they built along the “King’s Highway” between San Diego and Sonoma under Spanish colonial rule. Its beauty, acoustics, and location have made it a popular concert venue and tourist destination today. The Carmel mission was named a minor basilica by Pope John XXIII in 1960 and hosted a visit by Pope John Paul II during his 1987 North American tour.

Ashdown’s choral work, Missa Brevis de Requiem, is dedicated to the memory of both popes, and his Franciscan Pastorale, based on St. Francis of Assisi’s “All Creatures of Our God and King,” is among his most frequently performed works for the organ. It is tempting to imagine that John Steinbeck, who was friendly to Catholicism in his fiction and familiar with the legend and lore of St. Francis and the California missions built by the Franciscans, would be pleased.