What’s the latest on Cannery Row? In the years since 1958—when Monterey, California’s Ocean View Avenue was renamed Cannery Row in recognition of John Steinbeck’s 1945 novel—Cannery Row has inspired books about Steinbeck’s characters, his friend Ed Ricketts, and members of the circle that revolved around Ricketts’ Cannery Row lab in the 1930s and 1940s, John Steinbeck’s most productive period as an author.

A primary objective of this book is to produce a vision of Cannery Row as it was, from which unfolds both its emerging and little-known ‘human history’ and a vivid background for John Steinbeck’s fiction. — From Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue

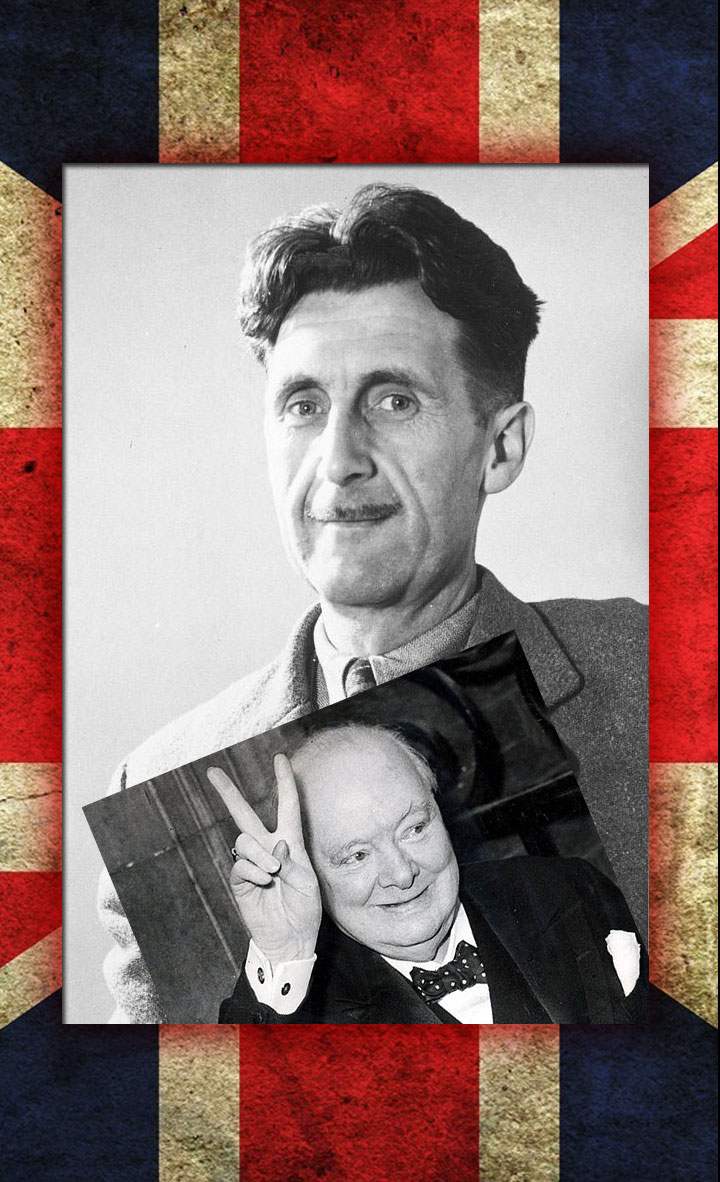

Among the best of the books is one that first appeared in 1986: Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue, by the Monterey, California area activist and writer Michael Kenneth Hemp, founder and chief historian of the Cannery Row Foundation. Fortunately for readers, an expanded new edition of Hemp’s popular pictorial history was released in January, printed on high-quality paper with a wealth of new images. But that’s only one reason to read Hemp’s book—which features attractive maps of Cannery Row and the Monterey, California Peninsula—before you visit John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

Michael Hemp, Cannery Row, and the Real Ed Ricketts

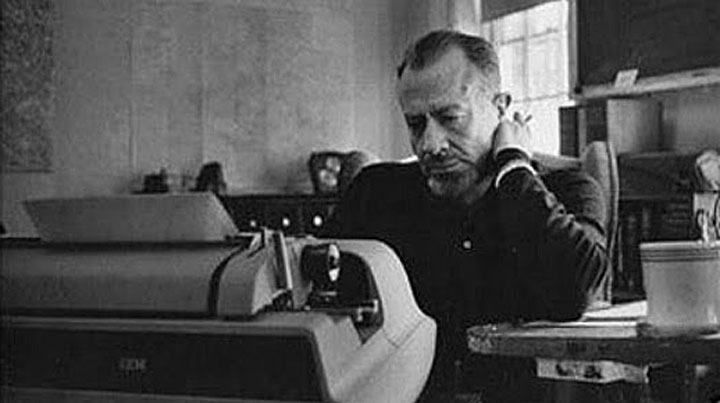

Another cause for celebration is Hemp’s command of colorful anecdote and vigorous vernacular, traits suggested by this photo in his office. Like other educated Steinbeck enthusiasts with a gift for expression, he writes in energetic English easily understood by readers of Steinbeck’s work. A published novelist and public speaker, Hemp is deeply engaged by the real Cannery Row, and his excitement is infectious. A Berkeley native and political science graduate of the University of California, he served as an Air Force Special Intelligence officer, and that shows too.

Cannery Row’s origins are a mixture of the rocky Monterey coastline and the toil and industry of the Orient. A Chinese fishing village, from which ‘China Point’ derives its name, [it] was established in the early 1850s and was devastated by fire in 1906. – From Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue

Hemp’s story of the rise and fall of Monterey, California’s sardine industry reads like a well-written reconnaissance report—precise, concrete, and focused on the facts as they occurred on the ground. Hemp’s knowledge of Cannery Row geography makes his history of the street easy to follow, a plus for fans of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row who are unfamiliar with Monterey, California. His emphasis on Ricketts’ career as a pioneering scientist and thinker puts the marine biologist’s collaboration with John Steinbeck in context, enhancing the appreciation of Ricketts’ role in the relationship and validating Hemp’s view that none of the “Doc” figures in Steinbeck’s fiction quite does justice to the real man.

New Evidence Concerning Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck

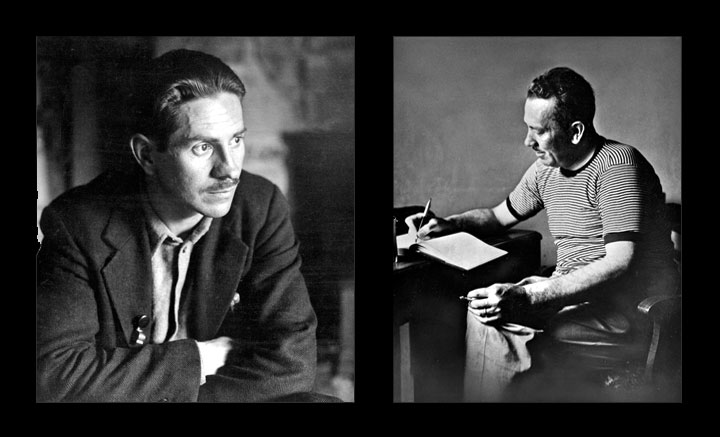

But why read the new edition of Hemp’s Cannery Row book if you already have the original? Simple. Because it contains new findings about John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, shown here, and fresh insights into Cannery Row’s past and prospects for the future. Steinbeck claimed that he first met Ricketts at the dentist’s in Monterey, California, a questionable assertion. Based on evidence from firsthand sources, Hemp identifies the actual meeting place as a private residence in Carmel-By-The-Sea, south of Pacific Grove and Monterey, California. By 1940 Steinbeck and Ricketts were predicting dire consequences for profit-driven overfishing, a major factor in Cannery Row’s postwar demise as the world’s sardine capital.

Fish cutting traditionally done manually by Chinese and Japanese and Spanish workers became cheaper and less specialized by nationality after the introduction of machine cutters. Slotted conveyors in which the sardines were placed were drawn under spinning blades that cut off the heads and tails and automatically eviscerated the fish.” – From Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue

Based on new science, Hemp provides new context for understanding the economic disaster created by rapacious technology and short-sighted greed, from the inception of the sardine industry in 1905 to its decline four decades later. Thanks to John Steinbeck, Cannery Row eventually came back as a tourist attraction, but commercial interests continue to cloud its prospects of becoming a world-class cultural destination. The Monterey Bay Aquarium, Cannery Row’s most prestigious nonprofit venture, nicely connects Hemp’s various concerns: John Steinbeck’s relationship with Ed Ricketts, the social and economic evolution of Monterey, California, and one-world ecology, the imaginative idea that permeates Sea of Cortez, the published record of Steinbeck and Ricketts’ most productive collaboration.

Pictures from the Past Published for the First Time

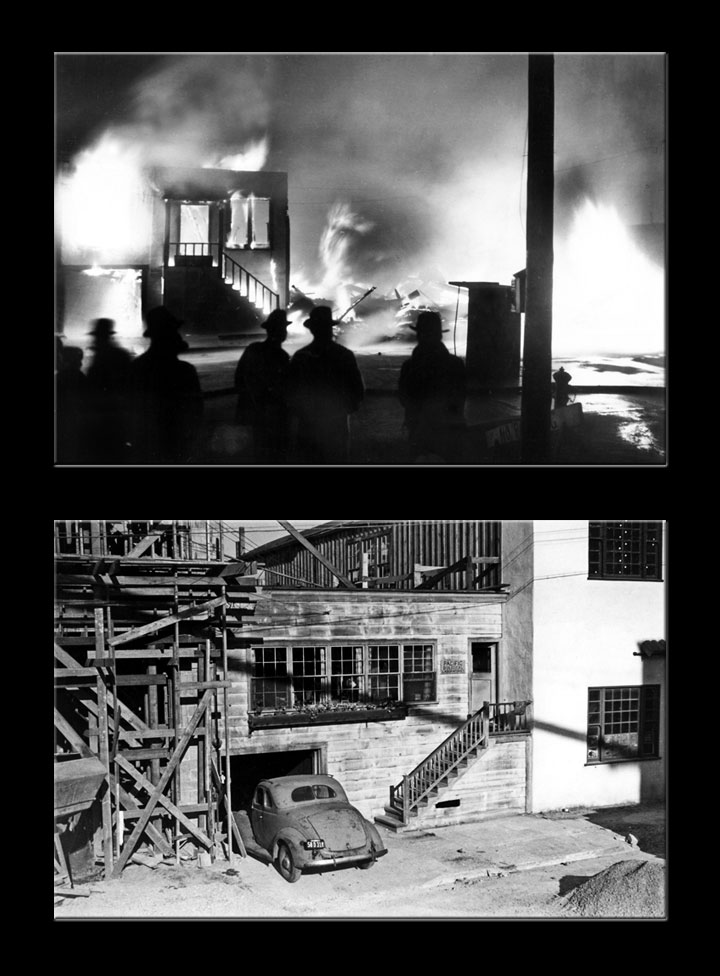

There is more to recommend Hemp’s history of Cannery Row than new text, however. The revised edition also contains a larger selection of photographs, printed at better resolution, than earlier versions. Among the most memorable pictures introduced for the first time are dramatic black and white images from Monterey, California’s colorful past, including photos of the 1936 Cannery Row fire that destroyed Ed Ricketts’ lab, shown here, and a 1948 police photo of a mortally injured Ricketts, lying on the ground beside his stalled Buick after being hit by a train near Cannery Row.

There has been a degree of controversy over just how John Steinbeck met Ed Ricketts. John Steinbeck writes that it happened in a dentist’s office, but we know John is, on occasion, given to ‘fiction’ when it comes to Ed Ricketts. The actual location and conditions under which Steinbeck met Ed Ricketts only came to light in 1991. – From Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue

Even glimpses of lighter moments foreshadow a dark future. One image printed here for the first time is a group shot of Ricketts, his lover Toni Jackson, and her daughter Kay taken by Ricketts’ brother-in-law, Fred Strong, in the mid-1940s. Toni, who eventually left Ed, is shown touching Kay, whose death from brain cancer in 1947 contributed to the demise of the relationship and the depression that some have associated with Ricketts’ death. It’s easy to see what each person in the picture saw in the others, and it’s hard not to feel a lump in the throat when thinking about their separate fates. Another Strong photo—a portrait of Ricketts made circa 1936—is almost as painful, but for a different reason. Posed in a sport jacket, eyes open and fixed on an object or idea in the middle distance, Ricketts looks the part John Steinbeck wrote for him in Cannery Row—commanding and charismatic, but also possessed.

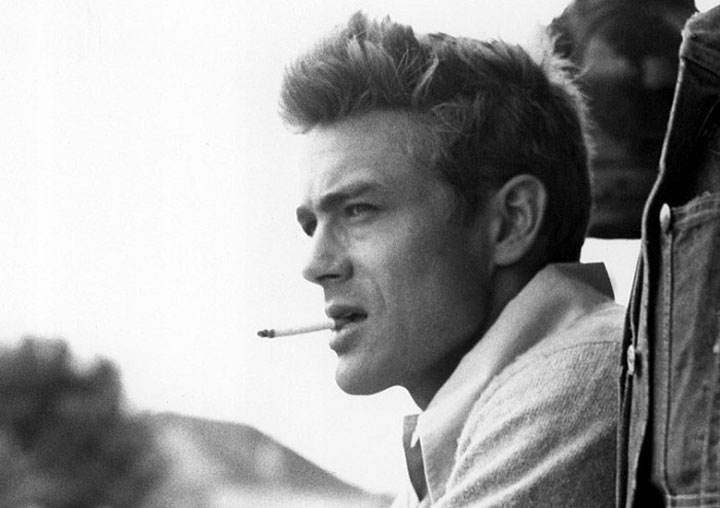

A Cannery Row Cult Classic Not Encountered Until Now

There were also motion pictures inspired by Cannery Row. Hemp maintains diplomatic silence about the failed 1982 feature film starring Nick Nolte and Debra Winger, spliced from John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday and directed by David Ward. But another movie, one that wasn’t based on Steinbeck’s fiction, contributes significantly to the conclusion of Hemp’s narrative. Shot in black and white on location in and around Monterey, California, Clash By Night is a bygone-times period piece—one that I was grateful to encounter for the first time.

Some of the filming . . . became entertaining in its own right, when an enterprising cannery worker, Jesse (‘Tuto’) Paredes, intentionally sent a can down the can chute sideways at the San Xavier cannery packing line, causing the line to be shut down—so all the cannery workers could rush to the windows to see Marilyn Monroe being filmed in a scene being shot on the street outside. – From Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue

Directed by Fritz Lang and produced by Harriet Parsons, it features Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Ryan, and Paul Douglas but became a cult classic because of Marilyn Monroe’s co-starring role as Peggy, a 20-year-old cannery worker. The story’s gritty setting is a Monterey, California coast so overfished by 1951 that Parsons and Lang had to work miracles to make a handful of sardines look like a haul. David Ward’s 1982 studio sets are elegant and drenched in color. But Fritz Lang’s fifties film noir seems truer to the crusty character of Cannery Row, at least to this viewer. Apparently Hemp agrees. His 1986 Cannery Row book mentioned Clash by Night in passing as a symbol of the street’s declining fortune. In the new edition he devotes six paragraphs, plus a photo, to the making and meaning of the sad movie shot in Monterey, California more than six decades ago.

Writing Fiction, Like John Steinbeck, from Science and Life

Hemp’s thoughtful treatment of Clash by Night stimulated my curiosity about the film; it also made we wonder what kind of fiction Hemp writes. A fascination with science, the same force that attracted John Steinbeck to Ed Ricketts, is evident throughout Hemp’s history of Cannery Row, so I turned to his 2008 scientific thriller—End of Lies: The Nadjik Pheromone—to sample his style as a writer of fiction. I’m only half-way through the novel, so its ending is safe with me. But the opening pages suggest that Hemp shares more as a writer with John Steinbeck than passion for science, Ed Ricketts, and Cannery Row.

He smiles, chuckling to himself. ‘There’s always a gang of ladies from the Monterey History and Art Association or National Steinbeck Center in Salinas that just have to see where John Steinbeck met Ed Ricketts.’ – From End of Lies: The Nadjik Pheromone

Recovering from the trauma of witnessing genocide in Bosnia, Hemp’s hero crashes at his boss’s vacation home in Carmel-By-The-Sea. Hemp’s fictional house is located next door to the actual bungalow where Ricketts and Steinbeck were introduced in 1930; the man who owns it in Hemp’s novel is an invented version of Hemp’s friend Tom Morjig, the real-life owner of the historic Carmel cottage. Like John Steinbeck—whose Cannery Row is, according to Hemp, 90 percent factual—the Monterey, California history and fiction writer uses real characters and real science to create a convincing story. Like The Grapes of Wrath, End of Lies is dedicated to the devoted wife “who made this book possible.” What greater compliment to a spouse—or homage to John Steinbeck—could any writer pay?

Period Cannery Row and Monterey, California photos reproduced from Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue courtesy of the Pat Hathaway Historical Photo Collection.