Houses in towns in the Midwest are built close together,

meaning when January winds scald raw the exposed skin

gusts travel in peristaltic waves. Spaces between houses

funnel a national anthem of snowfall and arcing drifts.

For months, everything is translated into Winterspeak.

In homes, to music, closing credits roll a disclaimer:

No animals were harmed in the making of this film.

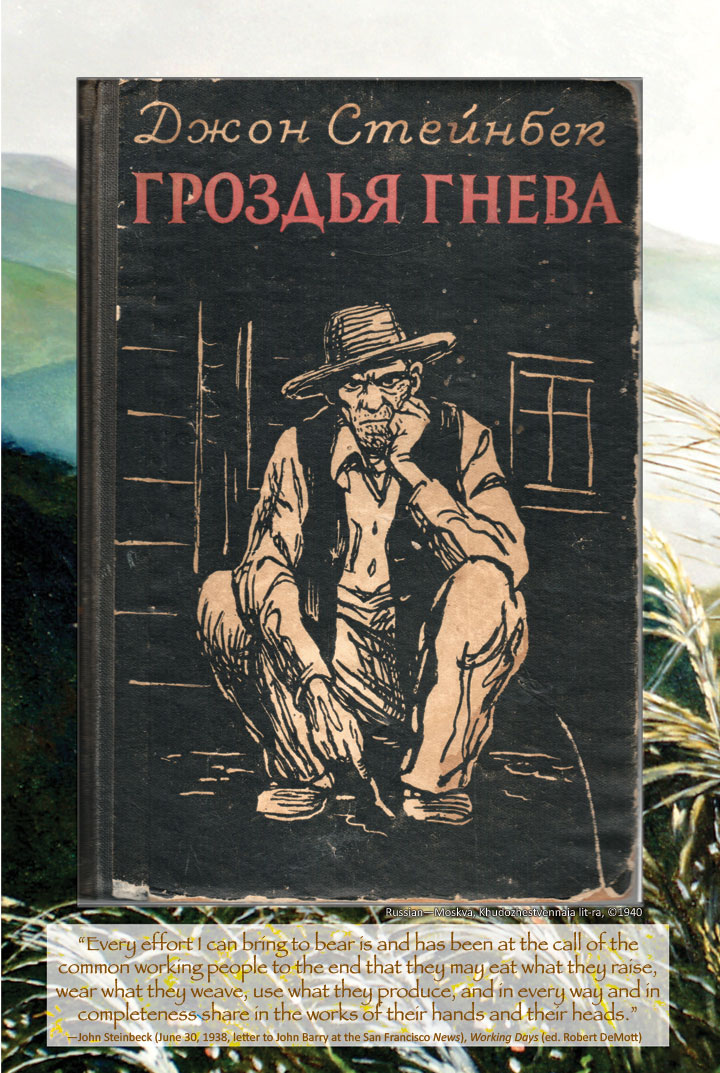

But these citizen-animals are harmed, complicit

in their subjugation. Most have become fluent

in thousands of dialects of silence. However,

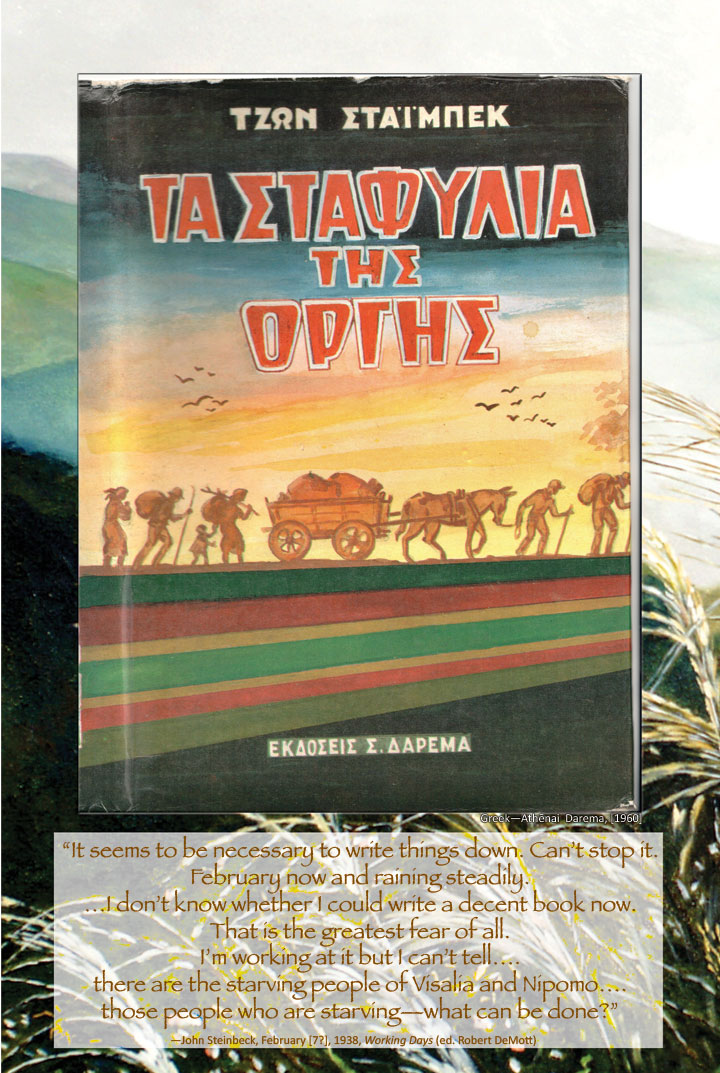

if history is to be trusted, soon the few will resist.

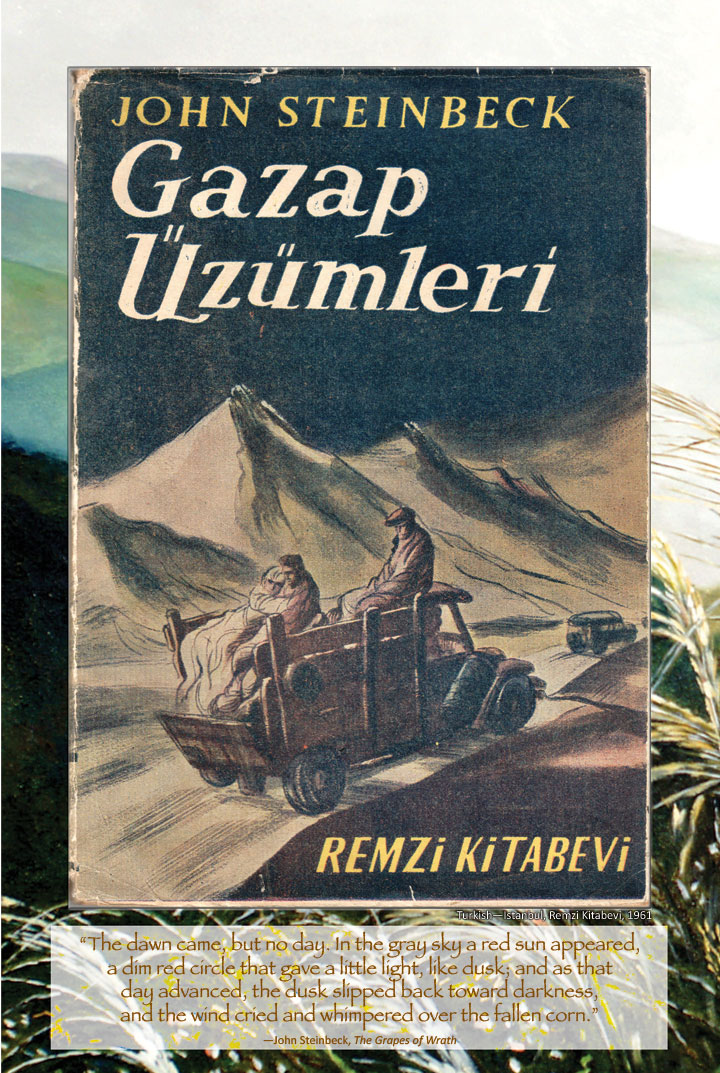

The horizon line will be radiant with grievances.

Squalls between structures will approximate voices.

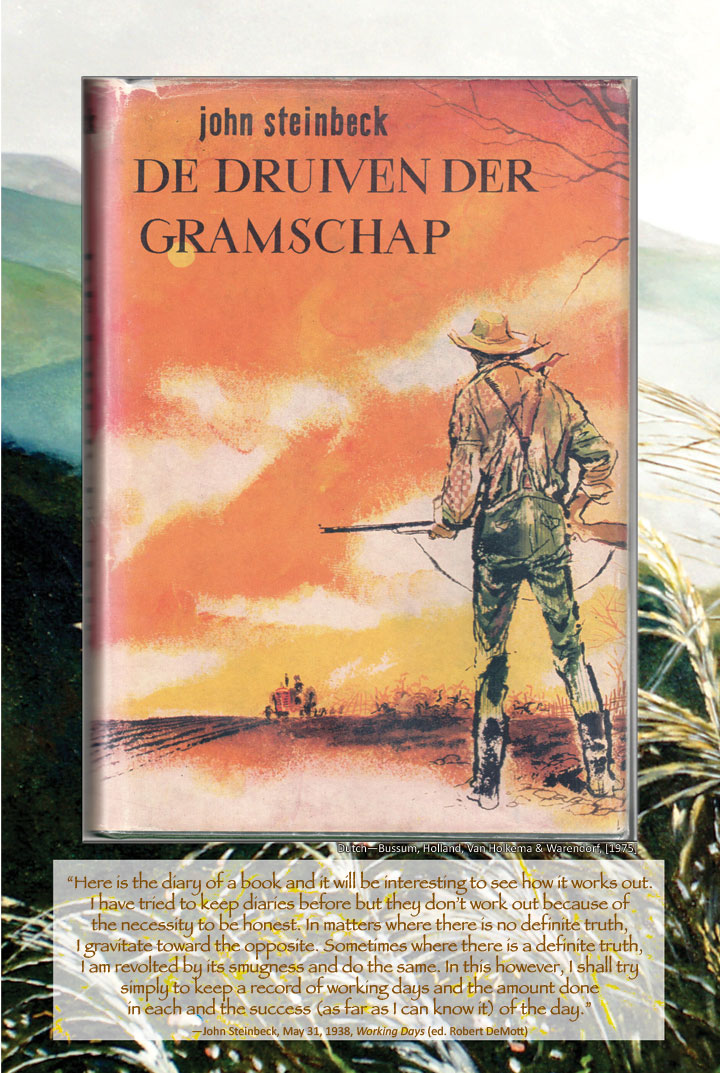

There will be a surf in the air. A tide. Sun-cut waves—

some waves defiant as they break into less brilliant light.