In the political novel The Iron Heel Jack London says the conflict

is always there, in our economic system, between capital and labor.

You can hear it in the way Janis belts out One of these mornings

you gonna rise up singing. Hendrix tosses in the lead-guitar-as-

exclamation-point so Janis can sing Child, you’re livin’ easy

and be sure we know the irony is that it’s a dream. Not real.

My friend, Stevie Conley, was at Woodstock. He tells me

Janis got falling-down drunk. That she talked a lot of shit.

She’s not talking shit here. She’s got a fear in her voice

says Jack London is right and we’re, all of us, doomed.

This version of the song is about that struggle between

wanting and needing and then receiving what you need.

The real trick is getting you to believe your daddy is rich,

your momma good looking. That we will rise up singing.

Archives for January 2014

Janis Joplin & Jimi Hendrix Perform “Summertime”

Cannery Row’s Human Parade: Helpful Hints for Better Training Design

As an instructional designer in business and industry I had the responsibility for preparing employees to face critical and risky tasks—ones that demanded courage and flawless creativity. It is a fact that most risky tasks are handled alone and not by a team or committee. To meet the challenges, I had to replace the usual classroom experiences with new training methods that considered the whole work environment. My methods were built on the ideas of the psychologist Carl Jung that were applied so well by John Steinbeck in his fiction and non-fiction, including Cannery Row, Sweet Thursday, The Log From the Sea of Cortez, The Moon Is Down, and East Of Eden. What follows continues the line of inquiry in my most recent post.

As an instructional designer in business and industry I had the responsibility for preparing employees to face critical and risky tasks—ones that demanded courage and flawless creativity. It is a fact that most risky tasks are handled alone and not by a team or committee. To meet the challenges, I had to replace the usual classroom experiences with new training methods that considered the whole work environment. My methods were built on the ideas of the psychologist Carl Jung that were applied so well by John Steinbeck in his fiction and non-fiction, including Cannery Row, Sweet Thursday, The Log From the Sea of Cortez, The Moon Is Down, and East Of Eden. What follows continues the line of inquiry in my most recent post.

Like Carl Jung, John Steinbeck understood the principle well, as shown in a letter to John O’Hara, his friend and fellow writer:

“I think I believe one thing powerfully-that the only creative thing our species has is the individual lonely mind. Two people can create a child but I know of no other thing created by a group. The group ungoverned by individual thinking is a horrible destructive principle. . . . “

As a result of my study, it became very clear to me that while individuals were facing creatively demanding tasks alone, the physical and social environment in which the creative effort must be undertaken influences job-holder perception, judgment, problem-solving, and decision-making—and inevitably, success or failure.

Carl Jung, Cannery Row, and the Human-Persona Divide

In my assignments as a training program developer, I became curious about the influences of the work environment on the individual. My goal was to create a richer and more realistic learning experience. I had years of independent study of Carl Jung and was aware of his influence on John Steinbeck’s fiction and non-fiction. Both inspired my efforts and spurred my curiosity.

As a result of reading Jung and Steinbeck, I began to understand why particular types of individuals seem to gravitate to certain jobs. For example, the personality difference between the engineer- and customer service and marketing-types is typically dramatic. What did John Steinbeck have to say about this particular human-persona divide? It seemed obvious to me that the Cannery Row character Doc would not have made a successful sporting house manager like Dora, and that Mack would have been a poor replacement for Doc in the role of Caretaker for the Row. Strong characters all, but hardly interchangeable.

Delving deeply into The Log From the Sea Of Cortez—John Steinbeck’s collaboration with Ed Ricketts, the model for his Cannery Row character Doc—I was struck by the idea that a person’s social and physical environment is no more random than that of the tide pool creatures described by the authors:

“We wanted to see everything our eyes would accommodate, to think what we could, and, out of our seeing and thinking, to build some kind of structure in modeled imitation of the observed reality. We knew that what we would see and record and construct would be warped, as all knowledge patterns are warped, first, by the collective pressure and stream of our time and race, second by the thrust of our individual personalities. But knowing this, we might not fall into too many holes-we might maintain some balance between our warp and the separate thing, the external reality.”

A Cannery Row-Sweet Thursday Human-Type Continuum

A training program, physical environment has purpose, patterns, lessons, and consequences like those imposed by the surrounding tide pool environment on a biological specimen. The life in a peaceful, safe, and unchallenging tide pool may actually impede species evolution and survival. The microbes that infect us evolve and strengthen in response to antibiotics designed to kill them. Grapes from a difficult growing season often produce superior wine. Trainees who survive a practical-and stressful- learning environment may likewise perform better than others on the job.

Consider the social environment and social impact upon the denizens of Cannery Row in Sweet Thursday, John Steinbeck’s sequel to the earlier novel:

“To a casual observer Cannery Row might have seemed a series of self-contained and selfish units, each functioning alone with no reference to the others. There was little visible connection between La Ida’s, the Bear Flag, the grocery (still known as Lee Chong’s Heavenly Flower Grocery), the Palace Flop house, and Western Biological Laboratories. The fact is that each was bound by gossamer threads of steel to all the others—hurt one, and you aroused vengeance in all. Let sadness come to one, and all wept.”

Or, by contrast, the following passage from Cannery Row:

“The previous watchman was named William and he was a dark and lonesome-looking man. In the daytime when his duties were few he would grow tired of female company. Through the windows he could see Mack and the boys sitting on the pipes in the vacant lot, dangling their feet in the mallow weeds and taking the sun while they discoursed slowly and philosophically of matters of interest but of no importance. Now and then as he watched them he saw them take out a pint of Old Tennis Shoes and wiping the neck of the bottle on a sleeve, raise the pint one after another. And William began to wish he could join that good group. He walked out one day and sat on the pipe. Conversation stopped and an uneasy and hostile silence fell on the group. After a while William went disconsolately back to the Bear Flag and through the window he saw the conversation spring up again and it saddened him. He had a dark and ugly face and a mouth twisted with brooding. The next day he went again and this time he took a pint of whiskey. Mack and the boys drank the whiskey, after all they weren’t crazy, but all the talking they did was “Good luck,” and “Lookin’ at you.” After a while William went back to the Bear Flag and he watched them through the window and he heard Mack raise his voice saying, “But God damn it, I hate a pimp!” Now this was obviously untrue although William didn’t know that. Mack and the boys just didn’t like William.”

Individual Levels in John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down

Just as examining a biological specimen in its surrounding tide pool yields greater information than isolated examination in a laboratory, we can learn more about individuals by studying them within their physical and social environment than in solitude. Conceptual tools such as Carl Jung’s functional and attitudinal types and Jim Kent’s Gathering Place Roles (discussed previously in this series) further expand our horizon. Deeper drilling reveals why particular Jungian functional types and attitudes will gravitate naturally to specific Gathering Place roles.

As noted in the first of these blog posts, human beings range in maturity from simple, unconscious types to highly evolved individuals who are conscious about and in control of their lives. Now I would like add my observations about groups made up of members who have not achieved higher maturity:

1. If there is any social structure at all, the social body will be vertically directed by leaders who have realized how easy it is to influence the citizens to do their will, usually for selfish and evil reasons. “Tell the population anything and repeat it many times and they will believe it” (Adolf Hitler paraphrased).

2. Less-evolved citizens who have not awakened to the possibility of their unique self and self-direction and will easily surrender their freedom to father or mother figures, real or imagined, and remain unaware of the resulting personal cost.

3. Such followers do not actively direct their lives beyond providing for the basics of assuring food, shelter, and procreation.

4. They project upon external gods, including father and mother figures, and are closed to suggestions from outside the social group: all thinking has been entrusted to the mother or father figure.

5. Total leader-control is possible simply by publishing of a list of “ought-and-must” dictates.

6. The leadership will be threatened by anyone who refuses to surrender his or her freedoms. Given the usual absolute power of the leaders, it is simple to incite mass or MOB confrontation against those who threaten challenge or change, sometimes cruelly and violently.

Where individuals of higher maturity comprise the group the following can be observed:

1. The leadership unselfishly serves its citizens.

2. “Ought-and-must” dictates are almost useless to control the citizenry comprised of higher-evolved individuals.

3. The life of the citizens has more potential for happiness and completeness.

4. Within this positive and loving environment, interpersonal struggles will persist because everyone will not agree on every issue. There is a noticeable difference between interpersonal struggles within a loving social environment and the ones where there is virtual sibling-rivalry for the father or mother figure’s attention. Adolf Hitler actually encouraged such confrontation among his leadership.

5. Highly evolved individuals have learned that there is more in play in themselves than mere ego and have begun to explore and integrate newly discovered psychological territory. This is perhaps the most important step to becoming a complete individual.

6. The collective power for good often exceeds what would be anticipated from apparent resources. Unexpected strength and adaptability will come out of the positive and powerful phalanx of more mature individuals.

In The Moon Is Down, John Steinbeck portrayed a community of evolved (per my recent post, Level 3 and Level 4) men and women, dramatizing the power of such a phalanx in response to occupation by father-figure representatives of a distant and despotic leader. The Nazi spokesman advises the mayor to “think for” his people:

“’It is your duty to protect them from harm. They will be in danger if they are rebellious. We must get the coal, you see. Our leaders do not tell us how; they order us to get it. But you have your people to protect. You must make them do the work and thus keep them safe.’ Mayor Orden asked, ‘But suppose they don’t want to be safe?’ ‘Then you must think for them.’ Orden said, a little proudly, ‘My people don’t like to have others think for them. Maybe they are different from your people. I am confused, but that I am sure of.’”

With the various levels of individual evolution in mind, consider the history of freedom-loving Scotland with the citizens being served by the Stewart monarchy. Go back further, to the Britons and King Arthur—John Steinbeck’s ideal of dedication to duty and chivalry. Fast forward to the Ottoman Empire, where the rights of all religions were guaranteed by proclamation. Consider the social environment surrounding the Library at Alexandria—destroyed by Christians—where citizens of all cultures, ideals, and creeds mingled and freely shared their knowledge and wisdom.

Needs Analysis and Jung and Steinbeck’s Human Factor

In my instructional design career I was responsible for providing training in tasks as simple as completing personnel time records and as complex as monitoring and controlling complicated electric generating-station systems. As noted, my programs were also used to prepare teams of consultants to influence and support communities that were facing challenges. In many cases, my job required the analysis of complex systems and processes, human-to-system interface, and interpersonal and social issues, using Needs Analysis to define the gap between existing competency levels and those needed to do the job with greater expertise.

Needs Analysis provide the necessary information to design training models, proposals, and justification, cost-benefit, and standards. Technical and complex-process analysts normally have abundant technical and process data available for their task. But complex critical-skill competencies also include personal and interpersonal components such as individual jobholder style, strengths, weaknesses, creativity, perception, judgment, and decision-making, problem-solving, risk-management skills.

But the analyst’s intellect is as critical to the success of the process as the technical tools developed in preparation for the act of training. Yet the humanities side of the training is all too often ignored in the process. The briefest examination of technical-owner manuals shows how poorly qualified most computer programmers and engineers are to write useful guides for the non-technical user. Worse still, to an experienced instructional designer, the engineer’s boast that he has emulated the cognitive processes of the human mind in designing artificial intelligence and expert systems for human use is laughable at best.

When I awoke to the need for a more holistic critical skills-training perspective, little was available to guide me in the human elements of the equation beyond publications by psychological behaviorists such as Thomas F. Gilbert and Robert Mager. But their view was limited to statistically defined and empirically observable behavior and ignored the influence of individual will and social environment. In my opinion they were uninterested in the factors that form our uniqueness and individual creativity. To develop a more complete program I knew that a broader perspective was required, providing a bigger window from which to analyze work processes and standards in greater depth and detail.

The program developers I managed were almost exclusively specialists and technical experts inexperienced in or ignorant of the humanities. To do a more thorough job, their subject-matter expertise needed bolstering with knowledge of human factors, attributes, and cognitive functions. Failure to consider these essential elements within the context of a given task accounts for many problems, notably in military training, pilot training simulation, nuclear power plant operation, ship navigation, and other life-and-death tasks. The 1979 near- disaster at Nuclear Generating Station Number Two on Three Mile Island is a dramatic example of this danger.

Was John Steinbeck Right About Religion and Freedom?

But was John Steinbeck always right about the individual? In the forward to a later edition of A Russian Journal he was quoted: “The great change in the last 2,000 years was the Christian idea that the individual soul was very precious.” I disagree, and I think Steinbeck knew better. Historically Christianity has cruelly suppressed individual behaviors and beliefs that appeared to challenge official doctrine and church control. In this regard, it is a religion with much company in the parade of human history.

The suppression of individual freedom remains an impediment to the general improvement of the human condition. As Steinbeck showed in The Moon Is Down, the simple act of raising individual consciousness from Level 1 to Level 2 improves the quality of the collective. In East of Eden, written 10 years later, the original sin isn’t eating the apple of the tree, suggesting that Eden was incomplete without self-knowledge—the real fruit of the forbidden tree. Eve is denigrated by the religious for taking that first bite of freedom. To the contrary, I am convinced that Adam benefitted from the reported act of her original disobedience. I suspect that John Steinbeck agreed.

“It is, I think, exceedingly easy to define what ought to be understood by national honor; for that which is the best character for an individual is the best character for a nation; and wherever the latter exceeds or falls beneath the former, there is a departure from the line of true greatness.” (Thomas Paine)

This is the third in Wesley Stillwagon’s series on the application of John Steinbeck and Carl Jung’s insights in innovative corporate training program design. To be continued.

Of Mice and Men: After Robert Burns

This is my work, as the plow unearths

its burden of hunger from the page: seagulls,

their wheeling cry and strut among dumpsters,

pigeons, like Russian women knotted down

by their scarves, stooping and pecking

under park benches for that last morsel,

even the mouse, caught in a dishtowel at Greyfriar’s—

“The wee mice come free,” the barmaid quips,

and the meal continues with the mouse, the pigeons,

the seagulls on the windowsill, with the man hunkered

down on Cockburn St. with his blanket and pet ferret,

with all of us scavengers, not long for this world.

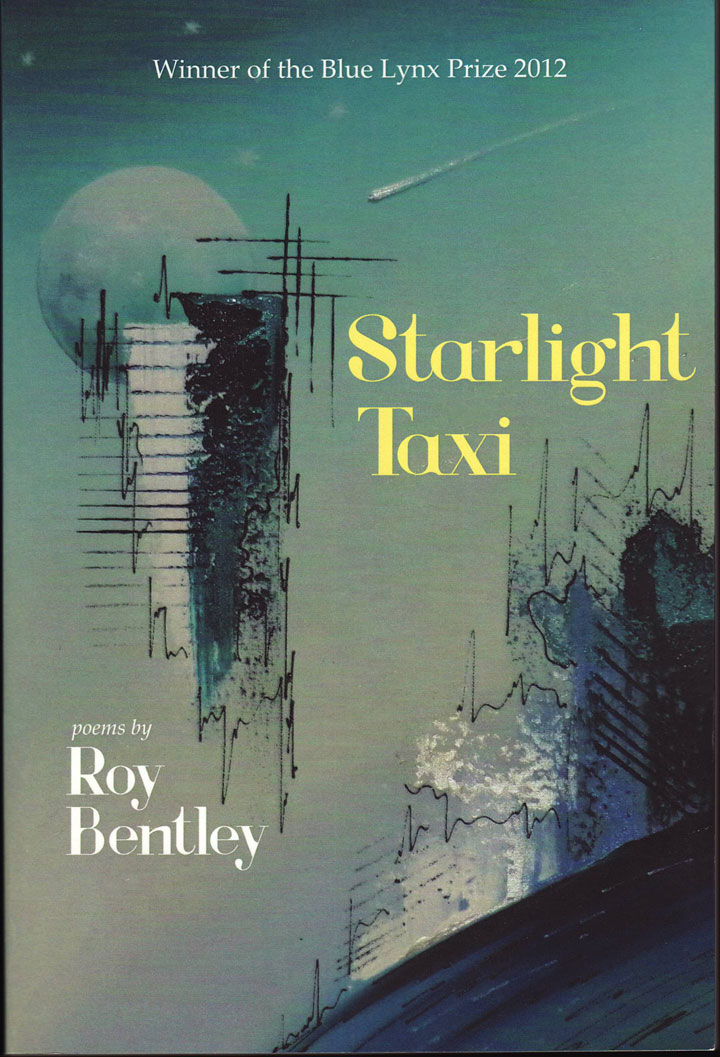

On the Road to America’s Heart of Darkness with Roy Bentley in Starlight Taxi

I’ve gotten off on poems often, transported to the heart of darkness or fields of light by great writers long departed from the living road. William Blake always topped my list of visionary favorites. Until I read Roy Bentley, however, I never encountered a living poet with a valid license driving far enough into the American interior to satisfy an anxious hitchhiker like me.

I’ve gotten off on poems often, transported to the heart of darkness or fields of light by great writers long departed from the living road. William Blake always topped my list of visionary favorites. Until I read Roy Bentley, however, I never encountered a living poet with a valid license driving far enough into the American interior to satisfy an anxious hitchhiker like me.

As a professional word-dealer I’ve been on the road with some of the best. Old William Blake; odd Emily of the New England Dickinsons; Yeats with his Anglo-Irish outrage and old-man monkey glands; Auden, mon semblable, mon frère! I was 24 when I got my doctorate in English with a dissertation on William Blake, but I didn’t know shit about life outside. The schoolboy prose I produced about dead poets with dead voices was all for show—and for the committee that now pronounced me man and Ph.D. Later of course I was forced to live and learn for real. Emily Dickinson said a poem should take off the top of your head. But what I needed after life hit was a heart job. Not Conrad’s un-particularized heart of darkness, no. My personal heart, which hurt.

The William Blake-John Steinbeck-Roy Bentley Connection

Thanks to two fine folks named John Steinbeck and Kate Fox, a writer and editor, I was finally introduced to Roy Bentley, the very poet my insistent inner doctor had been ordering. First came Roy’s emails, offering poems inspired by John Steinbeck for publication at SteinbeckNow.com. The voice I heard through the screen as I read sounded familiar—Southern, sensitive, sardonic, snotty when a subject deserved scorn, childlike when an experience was an epiphany. I saw lines I would write if I had Roy’s skill, which I don’t. I recognized the vision behind the voice, surreal yet familiar, like William Blake and his friendly angels.

I published Roy’s poems and asked for a meeting. A phone call had to do. As I was learning from reading his work, being on the road with Roy Bentley isn’t physical. It’s a mind-trip. If I could hear him, I could see him. A phone call would suffice.

Being on the road with Roy Bentley isn’t physical. It’s a mind-trip.

John Steinbeck didn’t like telephones, but Southerners generally do, and getting to know Roy long distance was like catching up with a high school friend. A self-exiled son of the border South like me, he now lives in Ohio, where I grew up, not far from his home state of Kentucky. Like William Blake’s village of Felpham in Sussex, England, however, Roy’s point of origin is more memorable than mine—a town named Neon in a county called Letcher—and his father actually split from his mother, something my dad contemplated but never accomplished. Roy liked girls and cars with the same Southern passion my country-boy father never outgrew. This was the first five minutes.

Like William Blake, Roy got married and (unlike William Blake) raised a family. Not a conversation-stopper, although I’ve always played for the other team. After all, John Steinbeck —also a William Blake fan and sexual frequent-flyer—was married repeatedly, and that hasn’t prevented Steinbeck from setting up residence in my sexually unorthodox soul. The image I got of Roy in our second five minutes is exactly what I saw in his poems: a man just like me, driving a lonely lane on the road to his heart of darkness destination. I was sure we’d be finishing each other’s sentences within an hour. But it happened in the five minutes that followed—and I talk fast.

The image I got of Roy in our second five minutes is exactly what I saw in his poems: a man just like me, driving a lonely lane on the road to his heart of darkness destination.

We played the Southern geography game: “Sure, Cincinnati, that’s not far.” “On yeah, that’s what I hate about the South too.” “No shit, I knew a guy exactly like that. Drugs and alcohol and the Army, Jeez!” “This job market sucks, and no, I wasn’t a great student either. You can probably guess why.” Hanging up, like breaking up, became hard to do. William Blake had his angels, John Steinbeck talked to his dogs. I have both and suspect that Roy does too. But we’re Southern boys who prefer two legs with a real mouth when it comes to human intercourse, and solitary driving on the road to the heart of darkness gets lonely with angels and dogs. We would need to talk some more, and probably again. Pissed off at the redneck revolution (“That’s why we left the South!”), we shoved Mom’s be-nice rule and discussed politics and religion—social no-no’s of Old South civility— before finally saying goodbye.

Starlight Taxi: High-Flying Poetry Printed with Style

Roy and I had clicked. As we clicked off, I suggested—and sent—the book I was reading, a prophetic novel written by Jack London in 1906 about a future fascist America. John Steinbeck, who grew up in London’s shadow, loved London’s work and probably read The Iron Heel before writing his wartime play-novella The Moon Is Down, set abroad rather than in the United States at the government’s insistence. George Orwell—John Steinbeck’s contemporary and another Jack London admirer—took the title of 1984 from The Iron Heel. Jack Kerouac, the On the Road prophet of the Beat Generation’s heart of darkness, was a later fan. Clearly Roy was ripe for Jack London. But I had my own reason for recommending The Iron Heel.

You see, Roy is a cosmic poet in the William Blake sense of the word. Big ideas pulse in tiny, telling details—what William Blake called “minute particulars”—in every poem, and one kind of apocalypse or another is always around the corner. As with Emily Dickinson, no word seems wasted; as with John Steinbeck at his best, no word seems wrong. So Roy’s work is here to stay, and I enjoyed the prospect of stumbling on the Jack London reference in a future poem by Roy Bentley, knowing secretly that our conversation was the source. My ancient William Blake dissertation collects dust, deservedly unpublished and ignored. A footnote explaining Roy’s artful Iron Heel allusion in a future anthology of American poets would make me feel what Roy calls “justified.”

I enjoyed the prospect of stumbling on the Jack London reference in a future poem by Roy Bentley, knowing secretly that our conversation was the source.

But Roy’s parting gift was much better than mine. The week after we talked I received an autographed copy of Starlight Taxi, his prize-winning collection of 65 tight poems printed by Lynx House Press on 95 thick pages the way fine poetry should be: surrounded by white space and unencumbered by prose. In top manic form, I tripped out as I read Starlight Taxi, Roy’s telephone voice still running in my head. I’m no Emerson, but I think I know how Emerson felt when he first read Walt Whitman, greeting the author of America’s “on the road” meme as a poetic original at the dawn of a great career.

I tripped out as I read Starlight Taxi, Roy’s telephone voice still running in my head.

Like John Steinbeck, my genetic code is programmed for English mountains and Celtic seas. Like William Blake, my angels always look British. Though he downplayed his non-Irish heritage, however, Steinbeck was German on his father’s side, and Sussex, despite Blake’s Englishness, seems as distant as Dusseldorf. But Roy Bentley is just like me: an Appalachian exile of uneasy English extraction, fully alive but moving with increasing anxiety on the road to America’s looming heart of darkness. Thanks to John Steinbeck and Kate Fox, I have found my living William Blake. He’s chosen the solo lane. But he likes company and he’s a skillful driver.

John Steinbeck’s Storied Artists: Monterey County Art in American History

American History Comes Alive in John Steinbeck Video

What did America’s Great Depression and San Francisco’s Beat Generation have in common? The unblinking eye of California’s most celebrated author, John Steinbeck, and the gallery of artists around him who lived and painted American history as it happened. Their striking stories are revealed in Steinbeck’s Storied Artists, filmed near John Steinbeck’s former home in Pacific Grove, California. How did the young John Steinbeck and his struggling artist friends survive the Great Depression? How did the aging author influence the later Beat Generation he claimed to dislike? How have succeeding post-Beat generations of Monterey County artists found impetus and inspiration for their art in Steinbeck’s damning vision of California’s Great Depression? Explore a neglected nook of American history—the world of John Steinbeck’s storied artists—with Steve Hauk, a Monterey County writer who relates amazing anecdotes about John Steinbeck, William Saroyan, and the storied artists who knew and followed them. As Steve shares tales confided to him by friends and family of John Steinbeck and his boisterous circle during a fateful period of American history, Shelley Cost—a Monterey County artist and art conservator—restores a Great Depression-era painting by John Steinbeck’s bigger-than-life friend, the California artist Armin Hansen, uncovering warm, vibrant colors and John Steinbeck-style characters obscured by layers of varnish and decades of exposure to the sun.

Mission Santa Clara Premiere of Steinbeck Suite for Organ Kicks Off 75th Anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath

Santa Clara University, located in the heart of California Steinbeck Country, kick starts the 75th birthday of The Grapes of Wrath on February 16 with the premiere of Steinbeck Suite, a dramatic piece of pipe organ music by the American composer Franklin D. Ashdown. Like James Welch, the pipe organ virtuoso (shown here) who will perform the premiere, Frank is a sensitive Steinbeck lover as well as a leading light in the world of organ music.

Santa Clara University, located in the heart of California Steinbeck Country, kick starts the 75th birthday of The Grapes of Wrath on February 16 with the premiere of Steinbeck Suite, a dramatic piece of pipe organ music by the American composer Franklin D. Ashdown. Like James Welch, the pipe organ virtuoso (shown here) who will perform the premiere, Frank is a sensitive Steinbeck lover as well as a leading light in the world of organ music.

Mission Santa Clara: Perfect for Artful Organ Music

The February 16 concert will start at 2:00 p.m. in Mission Santa Clara on the Santa Clara University campus near downtown San Jose. Mission Santa Clara is one of 21 ecclesiastical outposts established by early Spanish missionaries between San Diego and Sonoma and noted by Steinbeck in his travels throughout his native state. Like Monterey’s historic Carmel Mission, a place Steinbeck knew well, Mission Santa Clara is famous for its architecture, art, and acoustics. The February 16 Mission Santa Clara concert is part of Santa Clara University’s 2014 Festival of American Music, the kind of academic activity that appealed to the author.

Steinbeck and Pipe Organs: Music for Life and for Death

Steinbeck heard organ music growing up in Salinas, a town 60 miles south of Santa Clara, where he studied piano, sang in the church choir, and became a lifelong fan of opera, jazz, and the organ music of Bach. His first novel, Cup of Gold, ends with the sound of an organ chord reverberating in the mind of its dying protagonist, the pirate Henry Morgan. Organ music was played at John and Elaine Steinbeck’s 1950 wedding and at the writer’s funeral in 1968. With Steinbeck’s love of organ music, musicians, and theatrical effect in mind, Steinbeck Suite was commissioned by the former organist of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, the Salinas church depicted operatically in East of Eden, The Winter of Our Discontent, and Steinbeck’s “Letters to Alicia.”

Familiar Organ Music Inspired by Nights in Monterey

Frank Ashdown will be present for the February 16 world premiere of his new work by Santa Clara University Organist Jim Welch, California’s most celebrated concert organist and an alumnus of Stanford, the school Steinbeck attended sporadically before devoting himself to his writing. The February 16 program played on Mission Santa Clara’s classic pipe organ will also feature organ music by Richard Purvis, the subject of a recent biography by Jim Welch and the organist at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral following World War II. Purvis’s “Nights in Monterey,” a favorite piece of organ music for lovers of colorful sound, was inspired by camping trips made by the composer to the Monterey Peninsula at the time Steinbeck was writing East of Eden. It is possible that Steinbeck heard Purvis play the pipe organ at Grace.

Organ Music Written to be Heard, Like Steinbeck’s Fiction

A widely published composer of choral and organ music, Frank Ashdown has had his works performed at Grace, Salt Lake City’s Mormon Tabernacle, the Cathedral of Notre Dame, St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, and churches and concert halls throughout the world. A perceptive student of Steinbeck’s fiction, he writes as Steinbeck did: to be heard and appreciated by average people, not specialists. Jim Welch, who recommended Frank for the commission celebrating Steinbeck’s anniversary, comments: “From the opening movement, an homage to the humanity of The Grapes of Wrath, to the fiery closing toccata depicting the conflagration of Danny’s house in Tortilla Flat, Frank’s Steinbeck-inspired organ music will keep listeners on the edge of their seats. Mission Santa Clara’s reverberant sound, reverent atmosphere, and visual splendor are perfect for Frank’s Steinbeckian sense of acoustical theater and spiritual transcendence.”

The February 16 concert of organ music at Mission Santa Clara is open to the public. For tickets, see the Santa Clara University performing arts series website. Santa Clara University is located at 500 El Camino Real in Santa Clara, California, 10 minutes from San Jose International Airport and five minutes from Interstate 880. Take the Alameda Exit north and follow the curve in the road right as The Alameda becomes El Camino Real. The Santa Clara University campus entrance is on the left. Free parking is available in the new Santa Clara University garage near the campus entrance, and Mission Santa Clara is a two-minute walk from the garage. February 16 is a Sunday, but Californians dress casually. If this is your first visit, come early and drink in the beauty. Like The Grapes of Wrath, Mission Santa Clara is breathtaking. So are the organ music of Frank Ashdown and the organ virtuosity of Jim Welch, artists who love Steinbeck the way Steinbeck loved Bach.

The February 16 concert of organ music at Mission Santa Clara is open to the public. For tickets, see the Santa Clara University performing arts series website. Santa Clara University is located at 500 El Camino Real in Santa Clara, California, 10 minutes from San Jose International Airport and five minutes from Interstate 880. Take the Alameda Exit north and follow the curve in the road right as The Alameda becomes El Camino Real. The Santa Clara University campus entrance is on the left. Free parking is available in the new Santa Clara University garage near the campus entrance, and Mission Santa Clara is a two-minute walk from the garage. February 16 is a Sunday, but Californians dress casually. If this is your first visit, come early and drink in the beauty. Like The Grapes of Wrath, Mission Santa Clara is breathtaking. So are the organ music of Frank Ashdown and the organ virtuosity of Jim Welch, artists who love Steinbeck the way Steinbeck loved Bach.

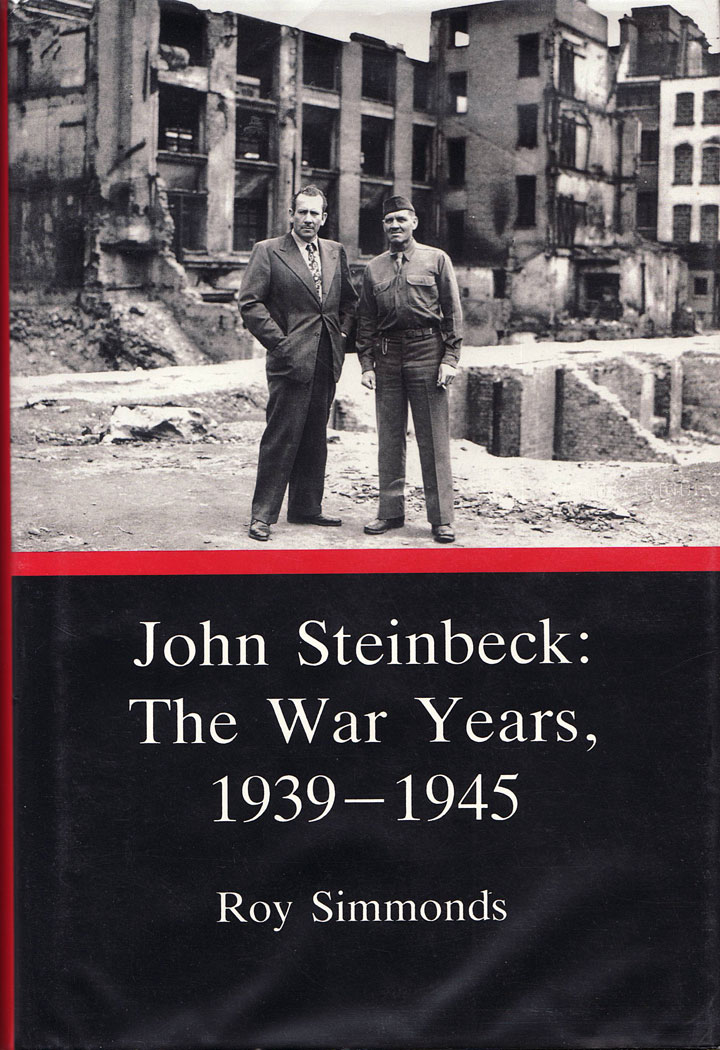

His Greatest Generation: The Lessons of John Steinbeck’s World War II Reporting

In staid Victorian England, Matthew Arnold, the author of Dover Beach, described journalism as “literature in a hurry.” Six decades and two world wars later, John Steinbeck confirmed Arnold’s lofty assessment of the correspondent’s craft, creating an enduring account of what he saw in Europe and Africa during the darkest days of World War II.

In staid Victorian England, Matthew Arnold, the author of Dover Beach, described journalism as “literature in a hurry.” Six decades and two world wars later, John Steinbeck confirmed Arnold’s lofty assessment of the correspondent’s craft, creating an enduring account of what he saw in Europe and Africa during the darkest days of World War II.

The Greatest Generation Goes to War

A member of the Greatest Generation who wrote and read poetry throughout his life, Steinbeck understood Arnold’s image of “a darkling plain/Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,/Where ignorant armies clash by night.” In his Steinbeck biography, the poet-novelist Jay Parini points out the acknowledgment by Newsweek magazine that the famous novelist was also a capable journalist, that his “cold grey eyes didn’t miss a trick, that with scarcely any note-taking he soaked up information like a sponge, wrote very fast on a portable typewriter, and became haywire if interrupted.”

Steinbeck understood Arnold’s image of ‘a darkling plain/Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,/Where ignorant armies clash by night.’

More than a decade after World War II, Viking Press released Once There Was a War, a collection of Steinbeck’s war reporting from June to December 1943—reporting that inserted the 41-year-old author of The Grapes of Wrath into the global madness that began when France and England declared war on Nazi Germany in 1938 and ended seven years later with the surrender of Japan, Germany’s chief ally.

Filing human interest stories in the gritty, humorous style of the American war correspondent Ernie Pyle, Steinbeck was stationed in London before shipping off to North Africa, where he experienced first hand the immediate aftermath of the Allied liberation of southern Italy. By that time Italy, the third element in the Axis triangle, had formally surrendered, although the battle for Nazi-occupied northern Italy would continue into 1944, costing literally countless British, American, and European lives.

Writing Steinbeck Biography in the World War II Years

Although considered by some a minor component of the Steinbeck canon, Once There Was a War nonetheless illustrates how John Steinbeck, working under the most difficult and dangerous professional conditions, was always conscious of leveraging his strengths as a writer engaged with the world. Steinbeck biography written since World War II acknowledges this facet of the author’s diverse career in varied ways.

In The Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer—the Bible of Steinbeck biography—Jackson Benson notes of Steinbeck’s World War II reporting that the author “would not try to compete for the hard news but would work to see things that had been overlooked or to see differently things that had already been reported.” Benson convincingly connects Steinbeck’s qualities as a fiction writer to his journalism: “He would become a correspondent of perspective, just as he had been a novelist of perspective—not telling us new, but seeing it new. In his concern for the commonplace and in his preference for the ordinary soldier, he became in many ways a correspondent much like the war journalist he admired the most, Ernie Pyle.”

‘He became in many ways a correspondent much like the war journalist he admired the most, Ernie Pyle.’

Focusing on a perturbed period of Steinbeck biography in John Steinbeck: The War Years, 1939-1944, Roy Simmonds speculates about the aging author’s ulterior motive in signing on as a front line correspondent at the height of World War II: “There is little doubt that within defined parameters he seized the opportunity to use the dispatches—through the mouths of the servicemen he met, or sometimes writing on their general behalf—to draw attention to many matters he felt needed publicity and urgent rectification.”

‘There is little doubt that within defined parameters he seized the opportunity to use the dispatches—through the mouths of the servicemen he met, or sometimes writing on their general behalf—to draw attention to many matters he felt needed publicity and urgent rectification.’

Whatever his motivation, however, John Steinbeck knew how to enfold moments of simple human existence in a lyricism that rises above the horror of modern slaughter, as almost any sample of his World War II dispatches demonstrates:

“LONDON, July 10, 1943—People who try to tell you what the blitz was like in London start with fire and explosion and then almost invariably end up with some very tiny detail which crept in and set and became the symbol of the whole thing for them.

“’It’s the glass,’ says one man, ‘the sound in the morning of the broken glass being swept up, the vicious, flat tinkle. . . . My dog broke a window the other day and my wife swept up the glass and a cold shiver went over me. It was a moment before I could trace the reason for it.’

“The bombing itself grows vague and dreamlike. The little pictures remain as sharp as they were when they were new.”

. . . .

“On the imaginary line the children stand and watch the cargo come out. . . . How they cluster about an American soldier who has come off the ship! They want gum. Much as the British may deplore the gum-chewing habit, their children find it delightful. There are semi-professional gum beggars among the children.

“’Penny, mister?’ has given way to ‘Goom, mister?’

“When you have gum you have something permanent, something you can use day after day and even trade when you are tired of it. Candy is ephemeral. One moment you have candy, and the next moment you haven’t. But gum is real property.

“The grubby little hands are held up to the soldier and the chorus swells.’Goom, mister?’”

. . . .

“MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, October 6, 1943—You can’t see much of a battle. Those paintings reproduced in history books which show long lines of advancing troops are either idealized or else times and battles have changed. The account in the morning papers of the battle of yesterday was not seen by the correspondent, but was put together from reports.

“What the correspondent really saw was dust and the nasty burst of shells, low bushes and slit trenches. He lay on his stomach, if he had any sense, and watched ants crawling among the little sticks on the sand dune, and his nose was so close to the ants that their progress was interfered by it.”

John Steinbeck and Dad: Why World War III is Unthinkable

As John Steinbeck noted in his introduction, his World War II dispatches for the New York Herald Tribune record events as they occurred. “But on reading this reportage,” Steinbeck adds, “my memory becomes alive to the other things, which also did happen and were not reported. That they were not reported was partly a matter of orders, partly traditional, and largely because there was a huge and gassy thing called the War Effort.”

Roy Simmonds, the author of the only Steinbeck biography by an Englishman and a survivor of the Blitz, notes that Steinbeck understood but resented the “huge and gassy thing” produced by the fog of war: “Talking to [enlisted] men, Steinbeck discovers that what also troubles many of them are the lies, both of commission and omission, being fed to the folks back home.”

Steinbeck understood but resented the ‘huge and gassy thing’ produced by the fog of war.

From the body of the writer’s World War II reporting, one thing can be said for certain: John Steinbeck chronicled and explored humanity’s most destructive behavior with the same honesty and intensity that he invested in mankind’s most noble pursuits. Despite his reluctance to revisit his war reporting for publication in 1958—a reticence confirmed by every Steinbeck biography of note—the dispatches he produced for immediate domestic consumption stand as an enduring testament, not only for the Greatest Generation but for every generation that followed.

The dispatches he produced for immediate domestic consumption stand as an enduring testament, not only for the Greatest Generation but for every generation that followed.

My father-in-law, a proud World War II naval veteran named Jerry Hollingsworth, believes that another global war is simply unthinkable. In a recent message he echoed John Steinbeck, who explained this belief in 1958, in the introduction to Viking’s collection of his World War II dispatches:

“The next war, if we are so stupid as to let it happen, will be the last of any kind. There will be no one left to remember anything. And if that is how stupid we are, we do not, in a biologic sense, deserve to survive.”

John Steinbeck’s Disappearing Act after Travels with Charley

About six weeks after John Steinbeck returned to New York following his 1960 Travels With Charley road trip, he attended John F. Kennedy’s January 20 inauguration in Washington. Steinbeck, then 58, and his wife Elaine shared a limo ride that famously bitter-cold day with Kennedy adviser John Kenneth Galbraith, the celebrated economist, and Galbraith’s wife Catherine. The photo and video are from a documentary produced for an ABC Close Up TV program called Adventures on the New Frontier. In it the Steinbecks and the Galbraiths are seen praising Kennedy’s inauguration speech and making jokes. Although the Galbraiths went to the inaugural ball in Washington that night, the Steinbecks decided to stay warm and watch the affair on TV.

About six weeks after John Steinbeck returned to New York following his 1960 Travels With Charley road trip, he attended John F. Kennedy’s January 20 inauguration in Washington. Steinbeck, then 58, and his wife Elaine shared a limo ride that famously bitter-cold day with Kennedy adviser John Kenneth Galbraith, the celebrated economist, and Galbraith’s wife Catherine. The photo and video are from a documentary produced for an ABC Close Up TV program called Adventures on the New Frontier. In it the Steinbecks and the Galbraiths are seen praising Kennedy’s inauguration speech and making jokes. Although the Galbraiths went to the inaugural ball in Washington that night, the Steinbecks decided to stay warm and watch the affair on TV.

The Missing Last Chapter of Travels with Charley

John Steinbeck describes his and Elaine’s adventures in DC (although he fails to mention John Kenneth Galbraith) in “L’Envoi,” the short chapter he intended to be the ending of Travels with Charley. When the book was released, however, the last chapter—like the Steinbecks at the ball—was missing. It was finally published in 2002 by John Steinbeck’s biographer Jackson Benson and John Steinbeck scholar Susan Shillinglaw in America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction, more than 40 years after Travels with Charley.

How I Discovered the Truth about Travels with Charley

In 2012 I carefully compared Steinbeck’s travel narrative with his actual road trip in my own book, Dogging Steinbeck. Subtitled “How I went in search of John Steinbeck’s America, found my own America, and exposed the truth about Travels with Charley,” Dogging Steinbeck tells how I learned by reading Steinbeck’s own correspondence and his original “Charley” manuscript that his published account contains so many dramatizations, elaborations, and fabrications that it should no longer be considered a work of nonfiction, but fiction. For the latest edition of Travels With Charley, Penguin Group had Jay Parini amend his introduction to warn readers that the book was the work of a novelist and should not be taken literally.

Justified: A Poem Inspired by Elmore Leonard’s U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens

When it’s time for Raylan Givens, U.S. Marshal, to catch

a hillbilly bad-ass villain dressed in the uniform of the hills,

Levis and a T-shirt that says I Eat Cornbread and Beans

Shit Freedom, you, who discriminate against difference,

will likely feel nothing for whoever draws his Glock first.

This episode is your chance to ask why pain or incarceration

attend disenfranchisement and scarcity like a bad credit rating.

I hear selective memory at work in their story of America.

I see that two-timer lover called Democracy cheating on us.

I fight the romantic in me, my failing to see what’s before me

and act upon it as I would any truth about myself and others.

Still, I love the lie. And I have lived most of my life with it.

It’s about trying not to think the worst is true all the time.

And, if it is, how does that shape the next and next step?

Hillfolk practice the habit of holding fast, failing to change,

while the world offers alternatives that shape shift and erase

the biggest part of any account of good and bad becoming

about the same. Depictions of unfair exchange aren’t new.

And lawmen like Raylan may self-identify as Appalachian

then put multiple gunshot wounds in others because they can.

It might be the right time in our turbulent history to question

what we mean by justified. Angels charged by God to follow

certain hellbent kids around from birth and to keep them safe,

the same angels surveys tell us that over 87% of you believe in,

have failed utterly in the task or are not that skilled at their job.

Maybe darkness itself is an angel in a laurel thicket, wrestling

the deep fangs of wolfish winds for the souls of the departed.

All of whom passed from this life justified in their disbelief.

Poem: James Dean Kissing Julie Harris in East of Eden

Now the better future has its say.

Now the lovers open their mouths

of once-only flesh saying: Take this

longing in fair exchange for yours.

Cal, eager to earn his way, shamed

for having an old whore for a mother

then not so much disgraced as reborn

into a world where fortunes rise and

fall with the market value of beans.

The message: God would have to be

a dumbass of some cosmic magnitude

to favor dweeb-son Aron over this guy,

Cal, maybe not the Good Son but a hunk

of scorching lust to succeed, nonetheless.

That the object of Cal’s affection is his

brother Aron’s girl is her call, after all.

Free will means everything is up for grabs.

And maybe he’s dumbstruck by the offer.

But the kiss is in case there’s no heaven,

no God, this appalling existence a single

CinemaScope Paradise Lost upon which

to bestow any sort of hope of redemption.

What’s a boy to do but smooch the girl

and outshine Adam for good measure.