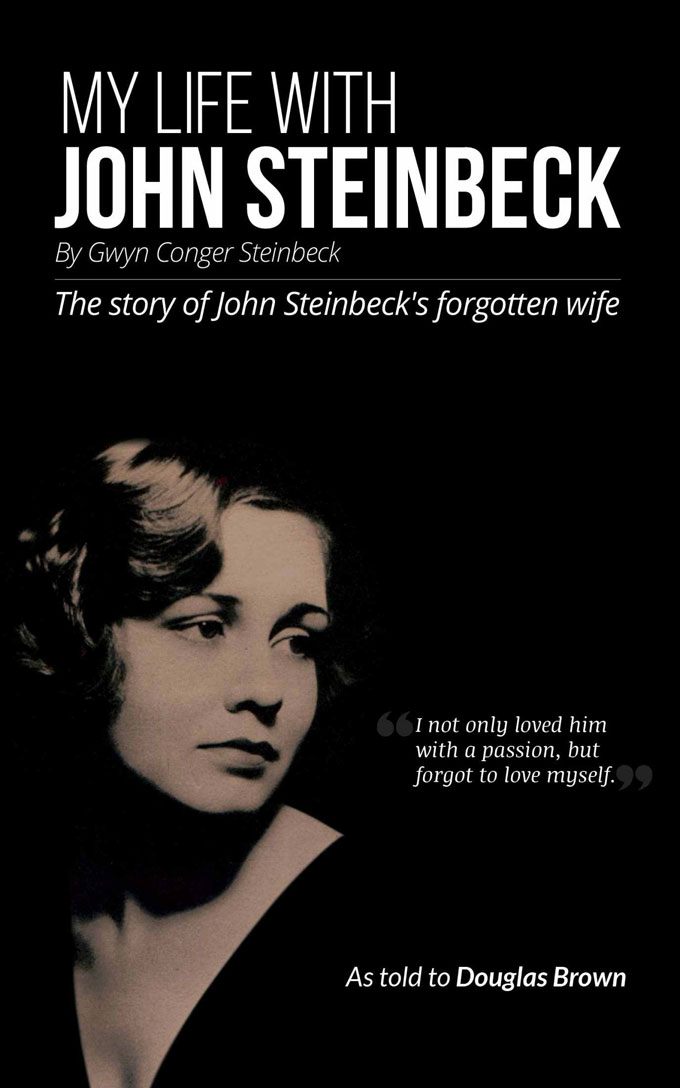

The publication of My Life with John Steinbeck, a kiss-and-tell marriage tale from the second wife’s point of view, is likely to raise more dust than it settles in Steinbeck country. Based on an edited transcript by the British reporter who taped interviews with Steinbeck’s second wife, Gwyn Conger Steinbeck, the book has a family-feud slant and an origin story that scholars and survivors have probable cause to challenge. A typescript of the taped interviews, which took place in 1971, has been out since 1976, in the form of a graduate student thesis readily available to researchers at various libraries and Steinbeck centers. Douglas Brown—the journalist hired by Gwyn to ghostwrite her memoir, then fired—was back in Britain when he passed away, in the 1990s, without ever publishing his rewrite of her account of an affair that started when Steinbeck was married to Carol Henning and ended in divorce, legal wrangling, and the birth of sons, now deceased, who both became writers. According to London’s Daily Mail, Douglas Brown passed the manuscript to his daughter before he died. She gave it to an uncle in Wales who showed it to a neighbor named Bruce Lawson, the man whose decision to publish now, 50 years after John Steinbeck’s death and 43 years after Gwyn’s, honors neither.

How John Steinbeck Read US-Mexico Relations: Book

Mexico was a magnet for John Steinbeck, a frequent visitor and sympathetic observer who explored the threats posed by assumptions he questioned to a culture he admired in fiction (The Pearl), film (The Forgotten Village), and history (the writer’s superbly researched introduction to Viva Zapata!). Fresh evidence that the feeling was mutual can be found in Steinbeck y Mexico: Una Mirada Cinematografica en la Era de la Hegemonia Norteamericana by Adela Pineda, Associate Professor of Spanish at Boston University and Director of Latin American Studies Program at Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies. “Steinbeck’s engagement with the history and the cinematic archive of revolutionary Mexico took place in an embattled field of political and cultural activity on both sides of the Río Grande, hence it could not be but complex and contradictory,” explains Pineda, winner of the Malcolm Lowry Fine Arts Literary Essay Award from the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes for Las Travesías de John Steinbeck Por México, El Cine y Las Vicisitudes Del Progreso. Pineda’s archival research revealed “the many facets of Steinbeck as a novelist, scriptwriter, film collaborator, and public intellectual”; writing a book about “Steinbeck going global from the vantage point of Mexico” is a fitting tribute to an admiring author whose research into a vanishing way of life became material for enduring art.

A Pilgrim’s Progress for Students of John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck studied Pilgrim’s Progress at his mother’s knee. Literally. John Bunyon’s allegory of sin and salvation was still family reading when Olive Steinbeck taught her pre-school son the alphabet 100 years ago and home libraries like the Steinbecks’ had books like Pilgrim’s Progress, so essential to Christian living that they were read aloud at family gatherings like the Bible. Like his father, John Steinbeck was often depressed about life, and Bunyon’s Slough of Despond colored his dark view of home town Salinas, a place of sloughs in both senses of Bunyon’s word—“swampy” and “characterized by lack of progress.” Like his mother, he had conflicting views about religion, “a curious mixture [for her, he said] of Irish fairies and an Old Testament Jehovah.” Her parents were frontier Calvinists, but she sent her son to the Episcopal church, where he stayed, nominally, until he died. He told his physician that he didn’t believe in an afterlife, but he wanted an Episcopal church funeral anyway and his fiction is full of religion gleaned from books he read in childhood—the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress—and mined for material in books still read today. Fortunately for readers without grounding in Steinbeck’s religion, Steinbeck’s biographer Jay Parini (in photo) has provided a Pilgrim’s Progress for the post-Christian century in The Way of Jesus, a spiritual autobiography by a gifted writer that also serves as a reader’s guide to Christianity in the spirit of Steinbeck’s fiction—progressive, companionable, and inviting participation.

The Way of Jesus: A Better Way to Understand Belief

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

An Essential History of John Steinbeck’s American West

Like Jackson Benson’s 1980 biography of John Steinbeck, the essential book on Steinbeck’s storied life, David Wrobel’s new history of the American West in Steinbeck’s formative period is an essential read for fans of the writer whose fiction brought the region to life for audiences everywhere. Designed for use by students and published by Cambridge University Press as part of the Cambridge Essential Histories series, America’s West: A History, 1890-1950 is compact, comprehensive, and compelling, organizing facts and creating patterns the way Steinbeck did in The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden, historical novels written in part to educate readers about movements of people, power, and ideas that made the American West first a beacon, then a bellwether, and finally a warning. Like Steinbeck, Wrobel presents the region’s history as a morality play we’re invited to watch about the sins of exceptionalism, expansionism, and economic domination.

Like John Steinbeck, David Wrobel presents the region’s history as a morality play we’re invited to watch about the sins of exceptionalism, expansionism, and economic domination.

Steinbeck’s history in this regard began before he was born. The economic cycles and social problems of of the 1890s affected his young parents, who settled in Salinas, where he was born in 1902, the year Teddy Roosevelt became president. The remedies for Gilded Age corruption put in place under Roosevelt, a New York blue blood who reinvented himself as a Dakota cowboy, brought good government to Washington and new attention to the West. Places like Salinas prospered, but they typified the paradox of progressive politics in America between the two Roosevelts. The same movement that broke up corporate monopolies, created national parks, and enfranchised women also imposed draconian social controls, including Prohibition, union-busting, and mass deportation. The Red Peril paranoia that became federal policy following World War I eventually led Salinas to experiment with what Steinbeck called fascism. He tore up the novel he wrote about the militarization of local government during a strike by lettuce workers, but by 1935 he had discovered his subject and set his course, reporting on migrant labor for the San Francisco News and writing The Grapes of Wrath, the protest novel that put into words the suffering and shame shown in Dorothea Lange’s photographs of migrant mothers and children.

Steinbeck tore up the novel he wrote about the militarization of local government during a strike by lettuce workers, but by 1935 he had discovered his subject and set his course.

Roosevelt progressivism at both ends of the period covered in America’s West gave Steinbeck the ideals, and events in California the ideas, expressed in The Grapes of Wrath. His upbringing in Salinas gave him the sense of empathy for people, animals, and nature that sympathetic readers recognize and respond to on first reading. When examining the beliefs and behaviors at work in the background, however, it’s also helpful to understand the sense of detachment from events and emotions he had to develop, with changes of subject and venue, in the novel’s aftermath. When he wrote about marine biology or war or the history behind the legend of King Arthur, he had the benefit of distance from his personal past and perceptions. Europeans since De Tocqueville have written about the United States with the same outsider’s advantage that Steinbeck enjoyed in England and David Wrobel has in writing about Steinbeck’s America.

Europeans since De Tocqueville have written about the United States with the same outsider’s advantage that Steinbeck enjoyed in England and David Wrobel has in writing about Steinbeck’s America.

A native of London with a yen for America, David Wrobel brought his coals to Newcastle by enrolling at Ohio University, where he immersed in Steinbeck under Robert DeMott and received his PhD in American studies. His understanding of the history behind The Grapes of Wrath and the intellectual currents of Steinbeck’s time has benefited immensely from his tenure at Oklahoma University, where he teaches, researches, and writes about Steinbeck and the American West and was recently appointed acting dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Oklahoma and California are his coordinates and Steinbeck is his moral compass in the case he makes for America’s West to 1950, the first of two volumes planned by Cambridge University Press. He has the English virtue of readability, along with Steinbeck’s eye for victims and losers, and Cambridge University Press designed the book to last, with just enough charts and graphs and not too many footnotes, placed at the bottom of the page where they belong. Its value is enhanced for followers of Steinbeck’s thinking by the author’s focus on the hidden costs of the West’s ascendancy and the line leading from the triumphalism of the past to the politics of the present. Five stars.

A native of London with a yen for America, David Wrobel brought his coals to Newcastle by enrolling at Ohio University, where he immersed in Steinbeck under Robert DeMott and received his PhD in American studies. His understanding of the history behind The Grapes of Wrath and the intellectual currents of Steinbeck’s time has benefited immensely from his tenure at Oklahoma University, where he teaches, researches, and writes about Steinbeck and the American West and was recently appointed acting dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Oklahoma and California are his coordinates and Steinbeck is his moral compass in the case he makes for America’s West to 1950, the first of two volumes planned by Cambridge University Press. He has the English virtue of readability, along with Steinbeck’s eye for victims and losers, and Cambridge University Press designed the book to last, with just enough charts and graphs and not too many footnotes, placed at the bottom of the page where they belong. Its value is enhanced for followers of Steinbeck’s thinking by the author’s focus on the hidden costs of the West’s ascendancy and the line leading from the triumphalism of the past to the politics of the present. Five stars.

The cover illustration is Thomas Hart Benton’s 1928 Western Regionalist painting “Boomtown.” Of special interest is the section on the Great Depression and the demographic shifts, racial divisions, and labor unrest dramatized in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and In Dubious Battle. It recalls the contributions made to the cause by Steinbeck’s co-workers Dorothea Lange, Carey McWilliams, and Pare Lorentz and explains the epic campaign of Upton Sinclair for governor in 1934 against the same forces that later waged war on The Grapes of Wrath. The author’s essay on California social protest literature, Steinbeck, Sinclair, McWilliams, and the WPA Guide to California appears in American Literature in Transition: The 1930s, an anthology edited by Ichiro Takayoshi.

The cover illustration is Thomas Hart Benton’s 1928 Western Regionalist painting “Boomtown.” Of special interest is the section on the Great Depression and the demographic shifts, racial divisions, and labor unrest dramatized in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and In Dubious Battle. It recalls the contributions made to the cause by Steinbeck’s co-workers Dorothea Lange, Carey McWilliams, and Pare Lorentz and explains the epic campaign of Upton Sinclair for governor in 1934 against the same forces that later waged war on The Grapes of Wrath. The author’s essay on California social protest literature, Steinbeck, Sinclair, McWilliams, and the WPA Guide to California appears in American Literature in Transition: The 1930s, an anthology edited by Ichiro Takayoshi.

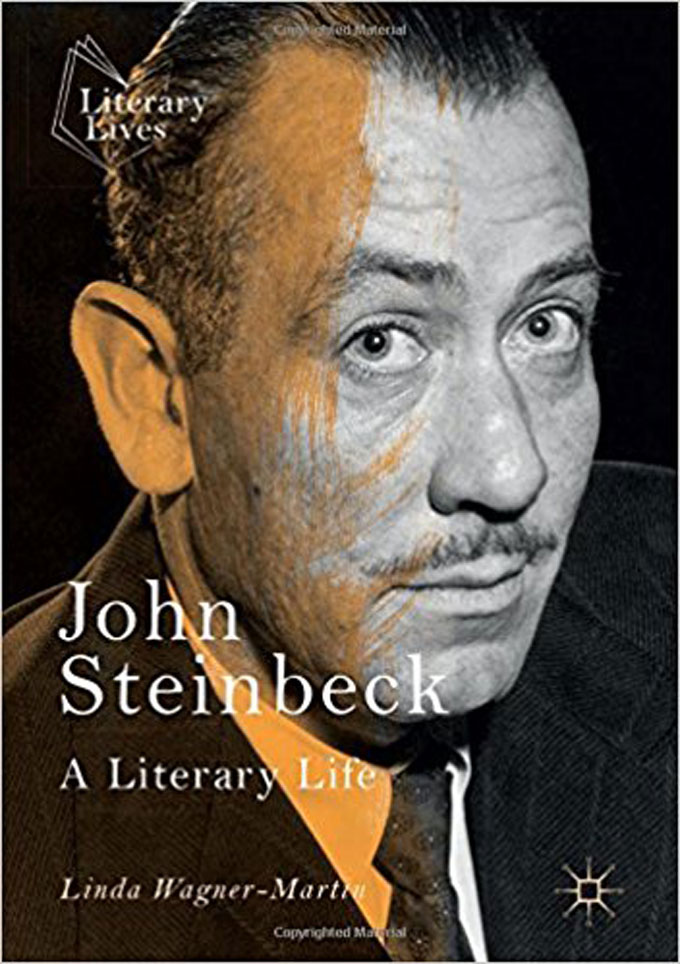

John Steinbeck: A Literary Life, Literary Criticism from Palgrave Macmillan

John Steinbeck: A Literary Life, a book of literary criticism and biography by Linda Wagner-Martin, winner of the Hubbell Medal for Lifetime Service to American Literature, has been released by Palgrave Macmillan, the international academic and trade publishing company. The work is the latest in Palgrave Macmillan’s Literary Lives series. Wagner-Martin, a professor of English and comparative literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, contributed earlier biographies of Emily Dickinson, Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath, and Toni Morrison to Literary Lives, described by Palgrave Macmillan as a “classic series, offering fascinating accounts of the literary careers of the most admired and influential English-language authors.” Chapters include “Steinbeck and the Short Story,” “Journalism v. Fiction,” and “The Ed Ricketts Narratives.” A hardback copy costs $109, the eBook version $85. Individual chapters can be purchased from Palgrave Macmillan in digital form for $29.95.

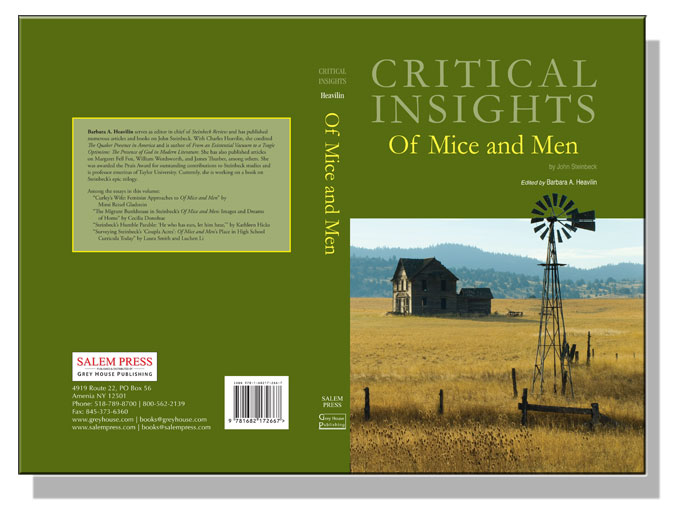

Critical Insights into John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men

Critical Insights: Of Mice and Men, a collection of literary criticism devoted to John Steinbeck’s Great Depression novella, is now available at Amazon.com. Edited by Barbara A. Heavilin with an introduction by Robert DeMott, it includes essays by Nick Taylor, Brian Railsback, Kathleen Hicks, Laura Smith, Luchen Li, Mimi Gladstein, Tom Barden, Danika Čerče, Cecilia Donahue, and Richard E. Hart, along with a Steinbeck chronology and a bibliography of scholarly writing about Of Mice and Men, a work that re-entered political discourse when the so-called Lenny rule was cited by defenders of capital punishment in a Texas case that recently made its way to the United State Supreme Court. Barbara Heavilin, a professor emeritus at Taylor University and the executive editor of Steinbeck Review, said this about the book’s relevance and the significance of literary criticism devoted to its understanding and appreciation: “I particularly wanted Critical Insights: Of Mice and Men to provide fresh, new insights on this novella, with articles provided by reputable Steinbeck scholars writing on their specialties. Mimi Gladstein, for example, writes on feminism, and Robert DeMott provides an insightful overview, among other well-known experts in the field of Steinbeck studies.”

How Steinbeck’s German Paperback Publisher Stayed Alive in Hitler’s Third Reich

Like other Anglo-American writers of German descent in the 1930s, John Steinbeck regarded the rise of the Third Reich with an admixture of anger, resentment, and resignation. Strange Bird: The Albatross Press and the Third Reich, a bright new general-interest book from Yale University Press, reminds admirers of Steinbeck’s writing today that reading his books in Nazi-occupied territory—particularly the 1942 novelette The Moon Is Down—could be downright dangerous. As author Michele K. Troy, a professor of English at the University of Hartford points out, however, the plucky German paperback publisher of Steinbeck, Hemingway, and other left-leaning English-language writers managed to stay in business from 1933 to 1941, despite the Third Reich’s draconian policy toward domestic dissent. But as Douglas J. Johnston notes in a recent book review, Hamburg’s Albatross Press “kept Anglo-American literature—and thereby Anglo-American ideas and values—alive in the heart of the Third Reich” not by doing good but by being profitable, producing popular paperback editions for foreign distributors who paid Germany in badly needed dollars and pounds. The firm’s iconic albatross (a source of guilt as well as a harbinger of hope) also paved the way for Penguin Books, Steinbeck’s equally enterprising paperback publisher in the United States.

From Travels with Charley to 30 Days a Black Man: Review

30 Days a Black Man: The Forgotten Story That Exposed the Jim Crow South, a new book by Bill Steigerwald about Ray Sprigle, the white Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter who investigated race in America by passing through the South as a black man, is now in bookstores, including the airport shop shown in this photo. Like Steinbeck’s social fiction from the 1930s, Sprigle’s syndicated series on segregation in the South increased understanding when it appeared in 1948, but also met resistance. Steigerwald’s account of the controversy will hold particular appeal for Steinbeck fans familiar with the back story of The Grapes of Wrath, and for sympathetic readers of Travels with Charley, the 1962 work in which Steinbeck touched on Sprigle’s theme. The connections are compelling. Steigerwald is a former reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette who made the opposite transition from Steinbeck, from newspaper journalist to full-time book author, in his career as a writer. His first book, Dogging Steinbeck, exposed fictional elements in Steinbeck’s account of the picaresque journey that ends dramatically in New Orleans, where white mothers scream at black children and Steinbeck discusses desegregation with a trio of sample Southerners, real or imagined, who typify the racial divide exposed by Ray Sprigle more than a decade earlier.

Why John Steinbeck Matters In Donald Trump’s America

“Steinbeckian” hasn’t achieved the currency of “Orwellian” as a term of obloquy for despotic language or behavior, but a cheerfully statistical item in The Atlantic reports that sales of John Steinbeck’s novel The Winter of Our Discontent—like George Orwell’s 1984—have spiked under the authoritarian shadow of Donald Trump, a bully and a blowhard of Steinbeckian, if not Orwellian, stature. While less apocalyptic than George Orwell’s nightmare dystopia, the world of The Winter of Our Discontent seethes with rancid resentment, greed, and xenophobia of the noisy, feculent variety increasingly associated with Donald Trump’s resurgent, alt-right America. The Atlantic article explains: “If the links between the events of the recent year and Steinbeck’s last book don’t seem entirely clear, The Atlantic’s review, published in 1961, is illuminating: ‘What is genuine, familiar, and identifiable [about the book] is the way Americans beat the game: the land-taking before the airport is built, the quick bucks, the plagiarism, the abuse of trust, the near theft, which, if it succeeds, can be glossed over—these are the guilts with which Ethan will have to live in his coming prosperity, and one wonders how happily.’” Steinbeckian is a good term for a bad leader who beat the American game, achieving personal prosperity and political power through means that can only be described as Orwellian.

What I Learned from The Winter of Our Discontent

I’m a small-town high school teacher and newspaper columnist, and every month I pick a new book, usually a literary novel, to read and recommend to my followers, who seem to enjoy what I have to say. Recently I chose The Winter of Our Discontent, and I confess it was because of the title rather than the content. But John Steinbeck’s novel is an apt expression of what I see as the winter of our discontent in the United States today, and it reflects the reality I face every day in my classroom.

When I chose The Winter of Our Discontent, I confess it was because of the title rather than the content.

As John Steinbeck fans know, The Winter of Our Discontent tells the story of a simple grocery store clerk, an outwardly respectable man named Ethan Allen Hawley, and his moral descent into corruption and crime. Steinbeck’s moral tale gave me plenty of “ah-hah” and “why, yes” moments—the kind of experience one expects from excellent literature, and the reason I recommended it in my column. As Steinbeck notes in the novel, “A man who tells secrets or stories must think of who is hearing or reading, for a story has as many versions as it has readers. Everyone takes what he wants or can from it and thus changes it to his measure. Some pick out parts and reject the rest, some strain the story through their mesh of prejudice, some paint it with their own delight. A story must have some points of contact with the reader to make him feel at home in it. Only then can he accept wonders.”

Steinbeck’s moral tale gave me plenty of ‘ah-hah’ and ‘why, yes’ moments—the kind of experience one expects from excellent literature, and the reason I recommended it in my column.

Though written years before the invention of the internet and social media, Steinbeck’s cautionary words are well-suited to our digitally-driven era. At this point in Steinbeck’s narrative, Ethan is thinking about how he has to shape his stories, or lies, to fit his hearers, and about a king in another story who told his secrets down a well because “It only receives, and the echo it gives back is quiet and soon over.” If only that were true today. For every tweet sent, there is usually a careless reader who misunderstands, misinterprets, or misappropriates the sender’s message, creating a backlash that becomes a raging beast that takes on a life of its own.

For every tweet sent, there is usually a careless reader who misunderstands, misinterprets, or misappropriates the sender’s message.

I don’t spend much time reading the comments people leave below online news stories or Facebook posts, but when I do I’m amazed at how far they wander from the point of the story or post. As Steinbeck knew, we take things out of context and add our own prejudices when we read or listen, and while I enjoy friendly banter as much as he did, I’m tired of the nastiness to which people increasingly resort when they don’t understand or approve of someone else’s point. I’m especially disgruntled when negative comments come from leaders who ought to know better and set an example for others.

As Steinbeck knew, we take things out of context and add our own prejudices when we read or listen.

As a school teacher, I recognized the truth in John Steinbeck’s unflattering portrayal of Ethan’s teenage children, particularly Ethan’s son Allen, and this line from the novel really made me laugh: “Three things will never be believed–the true, the probable, and the logical.” Often my students don’t believe me when I tell them something that is demonstrably true, then give instant credence to the next rumor they hear or read online, repeating it as if it were gospel truth. Fewer and fewer adults seem capable of logical thinking, so I probably shouldn’t be surprised. If you’re a teenager who isn’t capable of sound reasoning, you’re unlikely to believe someone who uses it. Like their parents, too many adolescents today are prepared to accept negative surface propaganda while doubting deeper truths.

Like their parents, too many adolescents today are prepared to accept negative surface propaganda while doubting deeper truths.

Is this because people want to take the easy way out of every problem, as Steinbeck suggests in The Winter of Our Discontent? Ethan is appalled when he learns that the patriotic essay for which Allen has won a cash award has been plagiarized. But Ethan’s reaction is hypocritical, because by this point in the story he has stooped pretty low himself. Unlike his father however, Allen shows no remorse, defending his behavior in much the same way my students defend their reliance on the internet so that they don’t have to do any thinking for themselves. Instead, when Allen’s plagiarism is exposed he gets mad at the person who ratted on him and utters the rallying cry of all cheaters and thieves: “‘Who cares? Everybody does it.’” Like John Steinbeck, I care, and I care very much. I’m weary of calling out cheaters like Allen in my classroom. Like Ethan in the novel, I sometimes think about throwing in the towel and calling it quits.

I’m weary of calling out cheaters like Allen in my classroom. Like Ethan in the novel, I sometimes think about throwing in the towel and calling it quits.

Ethan has had his own “Who cares?” moments growing up, but he had the advantage of a perfect teacher in his Aunt Deborah, a character I liked because I love words, grammar, literature, and everything associated with language, just as she does. When Ethan comes across the word talisman and asks her what it means, she tells him to look it up. As a result, he recalls, “So many words are mine because Aunt Deborah first aroused my curiosity and then forced me to satisfy it by my own effort. . . . She cared deeply about words and she hated their misuse as she would hate the clumsy handling of any fine thing.” When he finds the definition of talisman he discovers new words that he is forced to look up, too. “It was always that way,” he says. “One word set off others like a string of firecrackers.”

Aunt Deborah is a character I liked because I love words, grammar, literature, and everything associated with language, just as she does.

I highlighted the passage in the novel because I love the simile, and I love the way Steinbeck manages to incorporate his passion for words into an otherwise depressing story. Now, more than ever, we need Aunt Deborahs in our lives to make us aware of the beauty and magic of words at an early age. No doubt this idea impressed me because of the prejudices I bring with me to when I read John Steinbeck: others might roll their eyes because they don’t share my experience. Steinbeck fully understood the limitation we bring to our reading, and he wrote The Winter of Our Discontent in part, I believe, to help readers participate in the remedy he offers. Much has changed since The Winter of Our Discontent was written, but the deep truths to be discovered in Ethan’s story apply today. The winter of our discontent in the United States will end eventually, I hope sooner rather than later , but The Winter of Our Discontent by John Steinbeck will always have lessons for us—if we have ears to listen and love words enough to understand.