Twenty years ago I took photographs of Monterey County’s Steinbeck Country to present at the Steinbeck Centennial Conference held at Hofstra University in New York. The images, together with expanded text linking them to quotations from the writer’s work, were published as “The Settings for the Stories” in Steinbeck Review, Volume 6. Number 1, Spring 2009. In May 2021, I retraced the Salinas Valley route to see how the landscape looks two decades later. See “John Steinbeck’s Valley of the World Revisited: A Photo Essay” for images like this one, taken of a ranch in “the wilder hills” from Salinas Valley’s historic Old Stage Road.

John Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor Home on Sale for $18 Million

According to a February 19, 2021 New York Times real estate item that quickly caught the attention of Travels with Charley fans, the modest home in Sag Harbor, New York from which John Steinbeck and his poodle started their 1960 road trip can be yours for just under $18 million—more than Steinbeck and his wife Elaine paid in 1955, but less than the price of comparable waterfront properties for sale in tonier Long Island communities like the Hamptons. Steinbeck’s lifelong attachment to small, secluded spaces extended to the tiny writing cabin that he built on the 1.8-acre site and named Joyous Garde, after the Arthurian legend he learned to love as a boy. The online version of the Times real estate story included this comment from Bill Steigerwald, the Pittsburgh journalist who visited Sag Harbor (the venue for Steinbeck’s last novel, The Winter of Our Discontent) before setting out to discover the actual the driving route—and expose the narrative liberties—taken by John Steinbeck on his unsentimental journey “in search of America.”

“In 2010, exactly 50 years after Steinbeck and dog Charley left on the road trip around the USA that became Travels with Charley, I left his Sag Harbor house and retraced his route for my 100 percent nonfiction road book/expose, Dogging Steinbeck. I was kindly allowed to trespass on the property by the man who took care of it and I shot some video. I’ve never been confused with Steven Spielberg, and Peter Coyote was otherwise engaged, and I had no sound man . . . .”

“In 2010, exactly 50 years after Steinbeck and dog Charley left on the road trip around the USA that became Travels with Charley, I left his Sag Harbor house and retraced his route for my 100 percent nonfiction road book/expose, Dogging Steinbeck. I was kindly allowed to trespass on the property by the man who took care of it and I shot some video. I’ve never been confused with Steven Spielberg, and Peter Coyote was otherwise engaged, and I had no sound man . . . .”

Photo of John Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor property, by Gavin Zeigler for Sotheby’s International Realty, courtesy of the New York Times. Photo of Bill Steigerwald courtesy of truthaboutcharley.com.

Did John Steinbeck Know Patricia Michielssen or Her Painting of Cannery Row?

I was given two astounding assignments early in my time at the Monterey Peninsula Herald, now the Monterey County Herald.

One was to review the Monterey Jazz Festival shortly after arriving on the job—as a general assignment reporter. The paper’s usual jazz critic was indisposed. I have no ear for music. So, I decided to depend on dramatic instinct, and it kind of worked. My judgments more or less synced with the renowned jazz critic Leonard Feather. But Feather, a jazz pianist, could tell you why something was good or missed the mark. I couldn’t, or not very well. The paper gave me a bonus anyway.

The other was to take over the popular weekly “On the Waterfront” column. It was a good deal. Every week I got a few hours to roam the waterfront on my own. News people love that kind of freedom. The beat included stopping in wharf bars and hitching rides on boats—once to board the famous Calypso and meet Philippe Cousteau. His father Jacques Cousteau, an ocean conservationist ahead of his time, was back in France. And it was fun to hear the fishermen tell stories. For instance, an old Italian fisherman named Nino told me of a seal leaping onto the deck of his little boat to pilfer just-caught fish. Nino exclaimed and gestured, “How much you pay to have a ride?” The seal thought about it, devoured a cod, and hopped off.

Then there was the piece I did with the headline “The Last Fish Hopper.” I didn’t know what a fish hopper was, and the one floating just off the shore was no longer in use. As I came to understand it, fish hoppers were left over from the great sardine-catch days Steinbeck and others wrote of. Fishermen clued me in. The fish hoppers had flexible underwater piping that connected to the canneries. Fishermen could dump catches from boat to hopper, and from there the sardines would be funneled into the canneries. The fishing boats then immediately headed out to gather more sardines.

All this came to mind when I first saw the painting shown here. It is almost surely a rare painting of Cannery Row from the sea. Even old photographs of the Row from a boat are rare, paintings triply so. The large wooden structure, on the other side of a grounded splintered boat, is an out-of-commission fish hopper. The painting captures the muted coastal light filtering through the mist, sunlight touching purse seiners close by the back of the Cannery Row buildings.

It is such a fine painting, I thought it must be by one of the famous Peninsula artists of the time. I was wrong. It was painted by a woman named Patricia Michielssen, who was born (1929) and died (2017) in Watsonville, California, 30 minutes northeast of Monterey. John Steinbeck’s sister Esther had a home in Watsonville. The author visited often. Maybe Esther and Patricia knew each other. Maybe Steinbeck knew Patricia. Michielssen also spent many of her years in nearby Moss Landing. The coastal light she caught in this painting would have been seen often in that town’s harbor.

Otherwise, all I’ve been able to find as further evidence of her talent is two drawings—a windmill and a sprawling oak. If told they’d been done by Andrew Wyeth, I would believe it. Michielssen’s obituary mentions that she was a fine pen and ink artist whose work was displayed throughout the Southwest, but says nothing more about her artistic accomplishments.

The Cannery Row painting is not dated. Given the year of the artist’s birth, it’s unlikely it was painted before the late 1940s. The abandoned fish hopper also indicates a later date. By the end of World War II sardines had almost disappeared from Monterey Bay. So, it came after Steinbeck’s time of living in California, probably in the 1950s, maybe even the 1960s. If Steinbeck did see it on one of his trips back home, I am sure he appreciated the mood it creates. Artists were friends all his adult days—and he knew a fine painting when he saw one. Especially when it was a place he loved.

And, of course, Steinbeck would have known all about fish hoppers.

John Steinbeck Awardees Discuss “Giving Back”

A pair of celebrity philanthropists with marquee humanitarian projects and progressive political agendas will discuss “Giving Back” in a live-stream event that will end with one receiving the 2020 John Steinbeck Award, given by the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies “to honor an artist, thinker, activist who has made a significant contribution to causes that matter to the common person.” Sponsored by the Commonwealth Club of California, the online event features master chef and World Central Kitchen founder José Andrés, recipient of this year’s award, and the actor Sean Penn, who won in 2004. Tickets to the November 30 live-stream are $5.00 for Commonwealth Club members and $10.00 for non-members.

Composite image of José Andrés and Sean Penn courtesy Commonwealth Club of California.

The Best Introduction to Steinbeck’s Greatest Decade

The Western History Association, a professional society for scholars of the American West, was founded in 1961, the year John Steinbeck published his final novel, The Winter of Our Discontent, and wrote the final version of Travels with Charley, the work of “creative nonfiction” that continues to attract readers, and controversy, 60 years after Steinbeck’s road trip in search of an America he said he no longer understood. The Western history organization planned to hold its annual meeting in Albuquerque this year; fortunately for fans of John Steinbeck, having to meet online instead meant that the association’s October 14, 2020 presidential address by David Wrobel is now available to anyone looking for the best video introduction to John Steinbeck’s greatest decade of writing, from In Dubious Battle, “The Harvest Gypsies,” Of Mice and Men, and The Grapes of Wrath to The Moon Is Down and Cannery Row. Watch “Steinbeck Country and the America West” and find out how this writing became a British-born historian’s “window on the American West and nation,” from the New Deal to the Great Society—and how “Jeffersonian agrarian myopia” led to “racial blindness” in The Grapes of Wrath, and “creative fictions” about Oklahoma by the author of Travels with Charley.

Image of David Wrobel courtesy of the University of Oklahoma.

Dogging Steinbeck Started on This Day 10 Years Ago

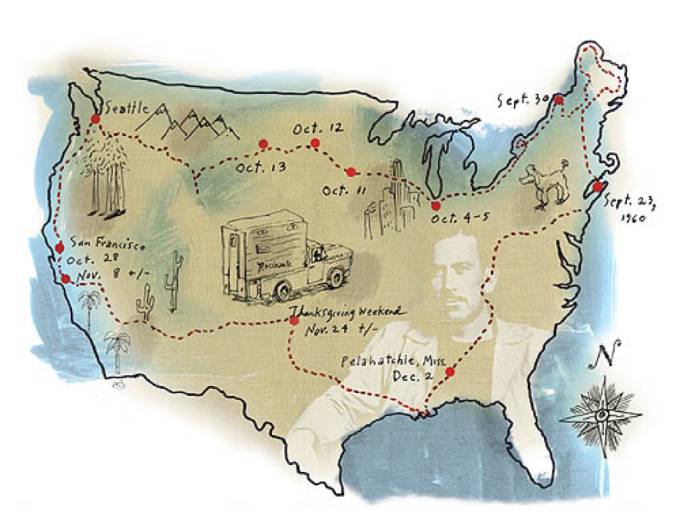

Sixty years ago this morning, on September 23, 1960, John Steinbeck and his poodle Charley set out from Sag Harbor on the iconic road trip around the United States that would become Travels with Charley in Search of America. Ten years ago this morning I set out from Steinbeck’s seaside house on the eastern end of Long Island and followed his 10,000-mile trail as faithfully as possible.

I admit I had my suspicions that Steinbeck had embellished Charley and had invented some of the colorful Americans he said he met at random. (I couldn’t help it—I was a veteran drive-by print journalist who knew how hard it was on the road to bump into the right people you need for a story.)

But my original intention was not to discredit Steinbeck, show him up, or prove that his 1962 New York Times nonfiction bestseller was a heavily fictionalized and disappointingly dishonest account of his actual journey. My main goal simply was to turn my solo adventure along the Steinbeck Highway into a book that would compare the America of Barack Obama that I saw in 2010 with the America of JFK and Nixon that Steinbeck saw in the historic fall of 1960.

Some of what I saw out my windshield on my mad 11,276-mile dash around the country can be seen in these 16 videos on YouTube.

I’m no documentary maker, as you will see. The videos are largely unedited and the wind is a recurring character. But I visit Steinbeck’s houses, the top of Fremont Peak, and many other places he stopped on his journey.

What I learned about the facts and fictions of Travels with Charley, the character of John Steinbeck, and the nature of America’s Flyover People is documented in my Amazon book Dogging Steinbeck. And Chasing Steinbeck’s Ghost is a guide to where Steinbeck really was on each day of a nearly 11-week search for the country he admitted he did not find.

Illustration by Stacy Innerst.

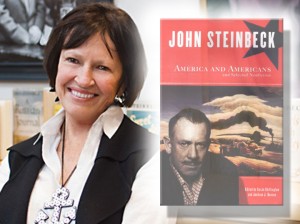

Zoom into Monterey Library’s “Cannery Row Days” Party

The author of Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck (William Souder, above) joins an all-star speaker lineup for the Monterey Library’s 75th anniversary publication party for Cannery Row, the “poisoned cream puff” of a novel resented by locals when it appeared but revered by readers ever since for its humorous depiction of human society—high and low—along Monterey’s historic waterfront. The six-week-long celebration kicked off on September 16 with a Zoom webinar led by veteran Steinbeck scholars Robert DeMott and Susan Shillinglaw (in photo left) and by Gerry Low-Sabado, a fifth generation Monterey native and well-known Chinese-American community preservationist. The six-week-long celebration includes lectures, films, and special events and ends on November 7 with public readings, virtual tours of Cannery Row, Monterey Bay Aquarium, and Ed Ricketts’s Pacific Biological Laboratories—the latter led by Shillinglaw and Mike Guardino of the Cannery Row Foundation—and a panel discussion of “Why We Read Cannery Row in 2020” that includes Souder; Donald Kohrs, librarian and archivist of the nearby Hopkins Marine Station; and Katie Rodgers, the pioneering editor of Ricketts’s letters, Renaissance Man of Cannery Row, and of Breaking Through: Essays, Journals, and Travelogues of Edward F. Ricketts. Registration for California’s “Cannery Row Days: A Novel Celebration” is free and open to the public (thanks to Zoom) wherever in the world COVID-19 days may have you cornered. Sessions in the series will be recorded and available for viewing at the Monterey Library website.

The author of Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck (William Souder, above) joins an all-star speaker lineup for the Monterey Library’s 75th anniversary publication party for Cannery Row, the “poisoned cream puff” of a novel resented by locals when it appeared but revered by readers ever since for its humorous depiction of human society—high and low—along Monterey’s historic waterfront. The six-week-long celebration kicked off on September 16 with a Zoom webinar led by veteran Steinbeck scholars Robert DeMott and Susan Shillinglaw (in photo left) and by Gerry Low-Sabado, a fifth generation Monterey native and well-known Chinese-American community preservationist. The six-week-long celebration includes lectures, films, and special events and ends on November 7 with public readings, virtual tours of Cannery Row, Monterey Bay Aquarium, and Ed Ricketts’s Pacific Biological Laboratories—the latter led by Shillinglaw and Mike Guardino of the Cannery Row Foundation—and a panel discussion of “Why We Read Cannery Row in 2020” that includes Souder; Donald Kohrs, librarian and archivist of the nearby Hopkins Marine Station; and Katie Rodgers, the pioneering editor of Ricketts’s letters, Renaissance Man of Cannery Row, and of Breaking Through: Essays, Journals, and Travelogues of Edward F. Ricketts. Registration for California’s “Cannery Row Days: A Novel Celebration” is free and open to the public (thanks to Zoom) wherever in the world COVID-19 days may have you cornered. Sessions in the series will be recorded and available for viewing at the Monterey Library website.

Decision to Close Steinbeck House Bad News for Salinas

In a July 24, 2020 San Jose Mercury News report that was picked up by wire services, plans were announced by the Steinbeck House in Salinas, California, to cease restaurant and catering operations indefinitely due to COVID-19. John Steinbeck was born in the handsome Queen Anne Victorian on Central Avenue near downtown Salinas in 1902; 70 years later a group of Salinas citizens created a nonprofit organization to purchase and preserve the home as an educational enterprise, supported by earned revenue from the restaurant and catering service run by volunteers on the first floor. Open five days a week to diners, many of them visitors from other states and countries, the restaurant quickly became a point of local pride, providing fine food at popular prices and feeding traffic to other local venues, including the National Steinbeck Center on Main Street. Says Dale Bartoletti—the retired Salinas educator and long-time Steinbeck House docent who has hands-on experience with the 122-year-old building—the decision to shutter the restaurant indefinitely was difficult but inevitable. “We donated several hundred dollars worth of food to a local church that provides daily meals to the homeless. Since then, we’ve served take-out dinner three nights a week and bought enough to see us through August 7, which will be our last Friday Night Dinner,” a popular feature of life in John Steinbeck’s home town before COVID-19 made dining out dangerous.

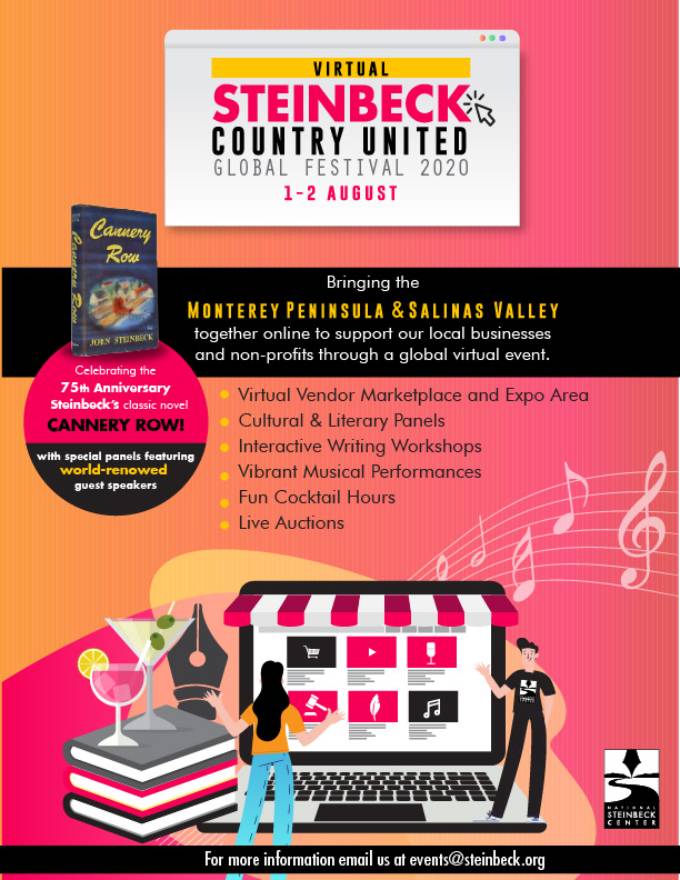

Making a Virtue of Necessity, Virtual John Steinbeck Festival Moves Online

Making a virtue of necessity, officials at the National Steinbeck Center have announced that the August 1-2, 2020 Steinbeck Festival will move online, motivated by COVID-19 and the need to think globally while acting locally to support the arts in John Steinbeck’s home town of Salinas, California. An annual event for more than a quarter of a century, the festival has experimented with dates, formats, and marketing strategies in the past, all in an effort to engage two contrasting constituencies—the multicultural community of Cannery Row and California’s Central Coast; fans of Steinbeck’s fiction from other states and countries—in honoring the famous local author who attracted the latter during his life by celebrating the former in his work. “Looking back, I don’t know why we haven’t done this before,” notes Michele Speich, the center’s director, of plans for this year’s “virtual platform” event. “We have a global audience, and we’re thrilled now to be able to share the Festival on a worldwide level and bring [it] straight to everyone’s home.” For speaker and schedule information, visit the Virtual Steinbeck Country United Global Festival sign-up page.

The Salinas History Project: An Update and an Invitation

At a recent agricultural technology summit held in Salinas, Steve Forbes called the small Central California city “the Ag-Tech capital of the world.” As director of the Salinas History Project at Stanford University, I have written a book which reconsiders the history of John Steinbeck’s home town from its incorporation as a city in the mid-19th century to its 20th century incarnation as an agricultural powerhouse—and its 21st identity as a laboratory for multiculturalism.

Numerous dissertations, academic papers, and books have focused on various racial and ethnic communities in and around Salinas, and on specific issues important to its evolution, including labor, environment, agriculture, and gang violence. The interconnection of these groups and issues has gained the attention of local leaders. So has the need for a more comprehensive account of the city’s history, and its place in the complex context of national and state history.

We began this work in 2016 knowing the obstacles we faced in achieving an analysis that would be broad and deep enough to shed new light on old problems. Primary among our challenges was one frequently faced by scholars of John Steinbeck’s life and work: written and recorded sources are scattered among multiple collections, some of which are more easily accessed and readily shared than others. The project is now complete and the resulting book is scheduled for publication this fall by Stanford University Press.

Readers with questions about the Salinas History Project are encouraged to contact me at mckibben@stanford.edu. Recently I gave a talk celebrating the 75th anniversary of Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row. It was video recorded by the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University, where I have taught since 2006, and it can be accessed at https://west.stanford.edu/research/works/cannery-row-75-virtual-event.

Photograph of historic Salinas, California downtown courtesy Salinas Public Library and Salinas History Project.