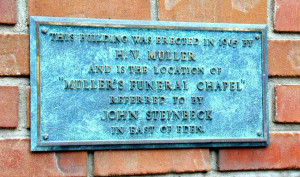

The recent death of Monterey, California businessman Frank Wright at age 98 served as a reminder that the life of Doc’s Lab—Ed Ricketts’s marine biology laboratory on Cannery Row—had two distinct phases. The 1930s and 1940s were the period of John Steinbeck and Ricketts and the artists and poets and philosophers who gathered around them. The 1950s began the Lab’s second incarnation as a men’s club of painters, cartoonists, teachers, journalists, lawyers, and business people founded by Frank and his friends—all with a passionate interest in Steinbeck and Ricketts and a way of life that was already fading into the past. Like the earlier, even more casual men’s club, Frank’s group met and socialized and partied in the Lab’s raffish rooms and outdoor concrete deck and holding tanks overlooking Monterey Bay. In the process they kept the Lab largely as it was, preserving it for posterity.

The Men’s Club That Saved Doc’s Lab

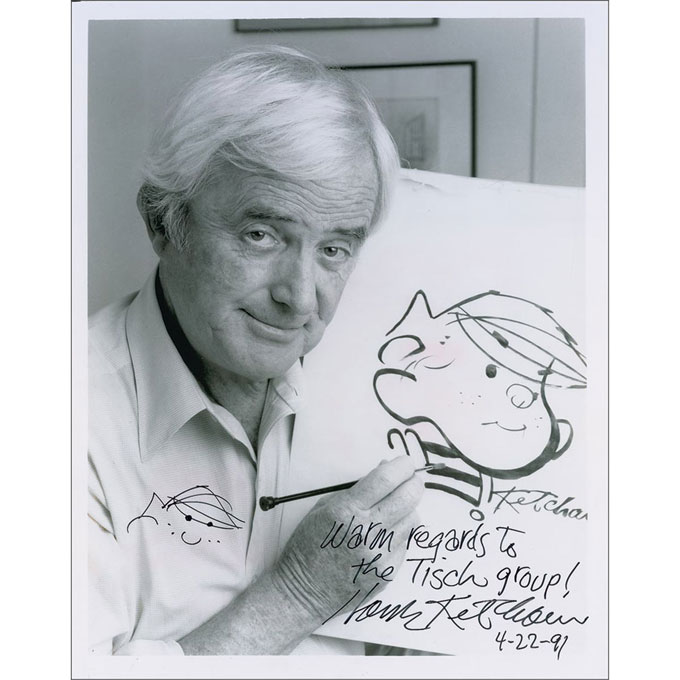

Frank met Ricketts after joining the Army in 1942, and they remained close until Ed died. In the early 1950s, Frank and two other men bought the Lab as a meeting place for their circle of artists, educators, and fellow enthusiasts. For a slim sampling of this second generation Cannery Row men’s club, there was Gus Arriola, the brilliant creator of the comic strip Gordo. Eldon Dedini, the farm boy from South Monterey County who became a successful and sophisticated cartoonist for Esquire and Playboy. Morgan Stock, the teacher and director who spearheaded the drama department at Monterey Peninsula College, which in turn named a theater for him. The irrepressible, crusading attorney Bill Stewart. The Dennis the Menace cartoon creator Hank Ketcham (in photo), also a serious painter. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts, they were creative types drawn together by a love of talk, drink, and music. The Monterey Jazz Festival grew from their collaboration. So did the idea of making Doc’s Lab a living museum, now under management by Monterey, California’s department of cultural affairs.

The End of an Era on Cannery Row

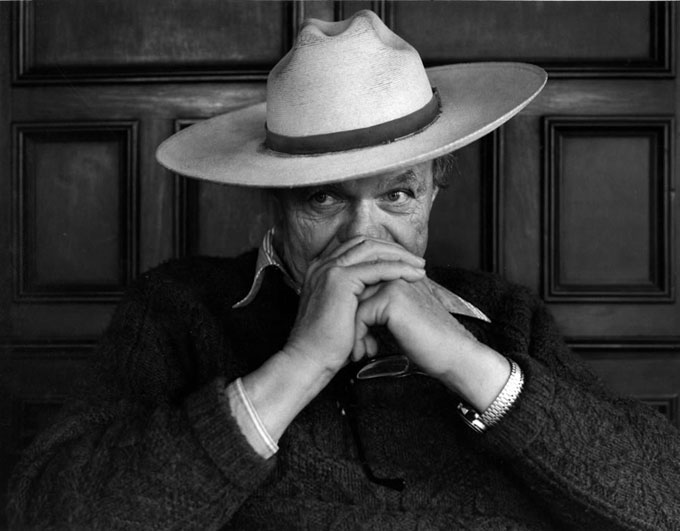

A personal memory: Years ago my late wife Nancy and I were walking along Cannery Row with Sue and E.J. Eckert (in photo to Nancy’s right). When we stopped in front of the Lab we got lucky. Frank Wright was standing on the stairs with Dennis Copeland, cultural affairs director for Monterey, California. Frank offered to give us a tour. He was a natural storyteller, warm and personable and charming, and when we left, walking out onto the bright morning sunlight of Cannery Row, the Eckerts said, “Boy, that was something!” They’ve never forgotten the experience. It was Frank’s gift to many when he was alive, and he was active well into his 90s. His death was indeed the end of an era.

Photo of Frank Wright courtesy Monterey County Weekly.