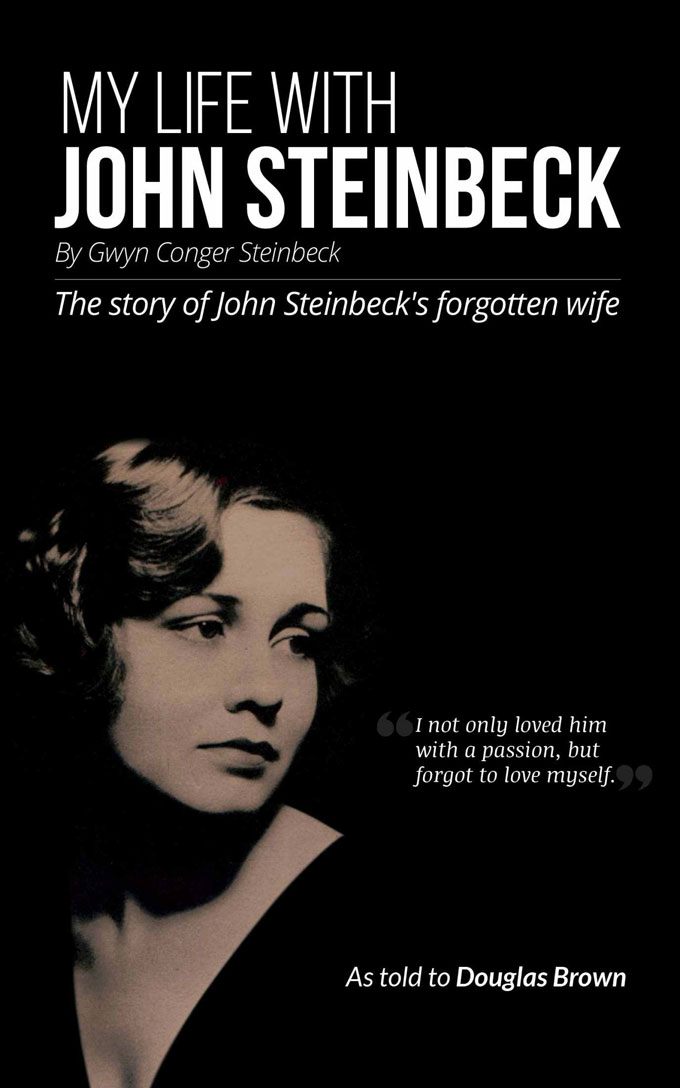

The publication of My Life with John Steinbeck, a kiss-and-tell marriage tale from the second wife’s point of view, is likely to raise more dust than it settles in Steinbeck country. Based on an edited transcript by the British reporter who taped interviews with Steinbeck’s second wife, Gwyn Conger Steinbeck, the book has a family-feud slant and an origin story that scholars and survivors have probable cause to challenge. A typescript of the taped interviews, which took place in 1971, has been out since 1976, in the form of a graduate student thesis readily available to researchers at various libraries and Steinbeck centers. Douglas Brown—the journalist hired by Gwyn to ghostwrite her memoir, then fired—was back in Britain when he passed away, in the 1990s, without ever publishing his rewrite of her account of an affair that started when Steinbeck was married to Carol Henning and ended in divorce, legal wrangling, and the birth of sons, now deceased, who both became writers. According to London’s Daily Mail, Douglas Brown passed the manuscript to his daughter before he died. She gave it to an uncle in Wales who showed it to a neighbor named Bruce Lawson, the man whose decision to publish now, 50 years after John Steinbeck’s death and 43 years after Gwyn’s, honors neither.

- Home

- Books

- Life

- Music & Media

- Places & Events

- Politics & Religion

- April 20, 2024

About John Steinbeck

Most read American writer of the 20th century. Born in California. Died in New York. Romantic. Realist. Rebel. More about John Steinbeck

FacebookTwitterLinkedInGoogle+ PinterestMySpaceStumbleUponYouTubeStay In Touch

Receive email updates and stay in touch with SteinbeckNow.com

Recent Posts

- New Video from San Jose State University on John Steinbeck: A Writer’s Vision

- Celebrate! Western Flyer Returns to Monterey Bay

- Henry Fonda’s Daughter, Jane Fonda, to Receive 2023 John Steinbeck Award

- A Chance Christmas Dinner with John Steinbeck in 1947

- Saved! John Steinbeck’s Retreat in Sag Harbor

- Celebrating Woody Guthrie’s Grapes of Wrath Connection

- John Steinbeck Haunts Malcolm Harris’s Palo Alto

- San Jose State Hosts Steinbeck Conference

- For John Steinbeck, the Rains in Pajaro Hit Home

- Photo Inspires Sumi Ink Portrait by Eugene Gregan

Masterful job, Will. Ashes to ashes and dust to dust bin. The lawyers will figure it out.

Nancy Steinbeck is a writer and the widow of John Steinbeck IV, John and Gwyn Steinbeck’s younger son.

Nancy Steinbeck was not John Steinbeck IV’s widow. She divorced him on February 28, 1988.

Re this book: caveat emptor! Between March and May, 1971, Douglas Brown made 11 audio tapes (equal to app. 259 pages of transcription) of his conversations with Gwyn that later served as the basis for “’The Closest Witness’: The Autobiographical Reminiscences of Gwendolyn Conger Steinbeck,” which Terry Halladay (a bibliophile and rare book expert working then at Jenkins Book Company in Austin, Texas) transcribed and edited and annotated as his 298-page Master’s degree thesis at Stephen F. Austin University in Texas in 1979. The original tape recordings and much other material were part of a sale by Thom Steinbeck and John Steinbeck IV of their mother’s estate. It is my understanding that until Halladay transcribed the tapes in a usable form, no print copy of the conversations existed.

Halladay, by his own admission, transposed his transcript of the interviews into a consistent first person narrative. I have used the Halladay thesis a number of times in my own writing on Steinbeck, notably for an essay on Steinbeck’s love poems to Gwyn, and as supporting material for a recent essay in Steinbeck Review about Steinbeck’s compositional journals of The Grapes of Wrath, The Wayward Bus, and East of Eden. The unpublished 1946 journal of the composition of The Wayward Bus took place smack dab in the middle of Steinbeck’s marriage to Gwyn and it presents another view of her account that, for academic fairness, is worth noting. By the way, so would Steinbeck’s letters to Gwyn, which are at Bancroft Library, in Berkeley. It is also worth noting that by her own admission, on May 28th, 1971, Gwyn’s final entry into the tape recorder were comments highly critical of Douglas Brown and there is evidence to believe that she wanted to terminate her relationship with him, because she felt he was deceiving her.

In comparing the Halladay version of the memoir with the one recently published and mentioned above, I am really struck by the difference in the voice and sometimes in the language of the two versions. Here is a snippet of Gwyn’s Foreword to the Halladay version: “When people will ask me why I chose to write this book, as I am sure they will, my reason will be that I wanted to show a side of John Steinbeck, a part of his nature and character which had been left alone…. I think there is a large group of people who are attempting to make what I would call a ‘little tin Jesus’ out of John Steinbeck, and he was not that. He was a human being, a very creative human being. I won’t say he was a good person all of the time, but I don’t think anyone is. His streaks of cruelty, his streaks of masochism, his hatreds and his jealousies were more pronounced because he was who he was.” And here is the version of the “Introduction” in the newly published book: “If you write a book, you have something to say. Long after we are gone, John Steinbeck can be studied. and his works read. His genius as a writer is undisputed, but what of the man? I do not know of anyone who has discovered the real key to him, but from this story may find it. He was a man of complexities, and of a unique nature. At times of anger at himself, he knew he was hurting other people, yet he was helpless to control his temper because of his selfishness. He was , of course, a literary giant. He was also a man of many lives. I know; I lived with him and shared his agonies, his struggled, his hatreds and jealousies of people and things. I shared his happiness an his joys. John Steinbeck was not a hero. he was only a tremendously complex man who could be very beautiful one moment then change into something very unbeautiful.” The patent difference in these two versions raises serious questions about the authenticity of the text. Gwyn’s Introduction to the recent published version is dated “Palm Springs, California, August 1972.” She died 4 years after the tape recordings were made, and 3 years after dating that Introduction. I am curious to know if she went thru the manuscript at a time in her life when she was drinking heavily and not always in great physical shape and smoothed out this current version that Lawson has published. I wonder, too,if there was even a transcribed copy of the tapes by then? Which leads me to guess that the current version was worked over extensively by Douglas Brown well after Gwyn died, which leads me to question the authenticity of the reportage. Whose witnessing are we getting? Is it primarily Gwyn’s account or is it mostly Brown’s elaborations? If the latter, without some kind of authorial attribution or caveat or explanation or clear line of textual chronology and evolution, the text will always be corrupt or at least be open to serious questions regarding its validity.

Gwyn’s account contains many good things, esp. her observations of Steinbeck’s writing protocols and habits, and some of the day to day details of their lives, but those useful historical moments will be lost in what could become half baked considerations of and attacks on Steinbeck as a monstrous male. The full historical, biographical, archival record wont always support that view.

Robert DeMott is the Kennedy Professor Emeritus of American Literature at Ohio University and the author of several seminal works of Steinbeck scholarship, including Steinbeck’s Reading and Steinbeck’s Typewriter, as well as books of poetry and prose about his other passions, music and fishing. As the second director in the distinguished history of the Steinbeck Studies Center at San Jose State University, he established a relationship of trust with Thom Steinbeck, the author’s older son, that led to the acquisition of Items including John Steinbeck’s Hermes typewriter and home movie footage shot by Steinbeck of the pet rat cited in Gwyn’s comments on her relationship with her husband.

Robert DeMott’s comments are right on, as is the assessment of STEINBECKNOW. This is a book to treat very gingerly, keeping whatever insights one may find in the territory of “possibly.” It is too bad that Mr. Lawson was not willing to work with DeMott or Jay Parini, or Susan Shilllinglaw (to pick three obvious possibilities) to try to verify and contextualize some of the claims put forth here — by Gwyn Steinbeck herself or by Lawson, who can tell?.

Paul Douglass is Professor of English at San Jose State University, the author of books and articles about modern philosophy and literature, and former of director of the Steinbeck Studies Center. He is also a musician.

Lawson’s book was in direct conflict to Thom Steinbeck’s instructions that he had no license to publish Gwyn’s works. That is why it is a sloppy bit of drivel. The lawyers are handling the copyright infringement. It’s so sad that Thom had to put up with so much chicanery.

Hi Gail. Re your comment that Nancy divorced your brother-in-law on February 28, 1988 – that’s very interesting. I’d like to know more about that period in John IV’s life, if possible? If so, could you kindly email me? Hopefully you can see my email address. Kind regards, Serena