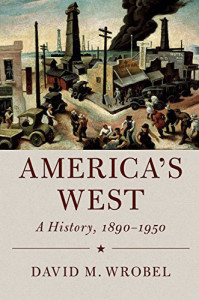

Like Jackson Benson’s 1980 biography of John Steinbeck, the essential book on Steinbeck’s storied life, David Wrobel’s new history of the American West in Steinbeck’s formative period is an essential read for fans of the writer whose fiction brought the region to life for audiences everywhere. Designed for use by students and published by Cambridge University Press as part of the Cambridge Essential Histories series, America’s West: A History, 1890-1950 is compact, comprehensive, and compelling, organizing facts and creating patterns the way Steinbeck did in The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden, historical novels written in part to educate readers about movements of people, power, and ideas that made the American West first a beacon, then a bellwether, and finally a warning. Like Steinbeck, Wrobel presents the region’s history as a morality play we’re invited to watch about the sins of exceptionalism, expansionism, and economic domination.

Like John Steinbeck, David Wrobel presents the region’s history as a morality play we’re invited to watch about the sins of exceptionalism, expansionism, and economic domination.

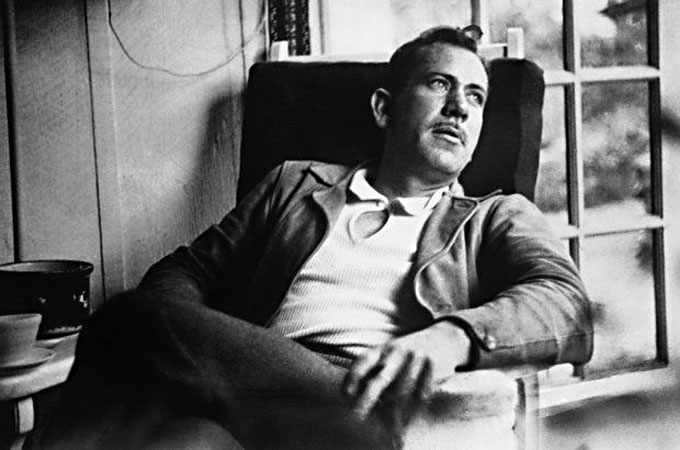

Steinbeck’s history in this regard began before he was born. The economic cycles and social problems of of the 1890s affected his young parents, who settled in Salinas, where he was born in 1902, the year Teddy Roosevelt became president. The remedies for Gilded Age corruption put in place under Roosevelt, a New York blue blood who reinvented himself as a Dakota cowboy, brought good government to Washington and new attention to the West. Places like Salinas prospered, but they typified the paradox of progressive politics in America between the two Roosevelts. The same movement that broke up corporate monopolies, created national parks, and enfranchised women also imposed draconian social controls, including Prohibition, union-busting, and mass deportation. The Red Peril paranoia that became federal policy following World War I eventually led Salinas to experiment with what Steinbeck called fascism. He tore up the novel he wrote about the militarization of local government during a strike by lettuce workers, but by 1935 he had discovered his subject and set his course, reporting on migrant labor for the San Francisco News and writing The Grapes of Wrath, the protest novel that put into words the suffering and shame shown in Dorothea Lange’s photographs of migrant mothers and children.

Steinbeck tore up the novel he wrote about the militarization of local government during a strike by lettuce workers, but by 1935 he had discovered his subject and set his course.

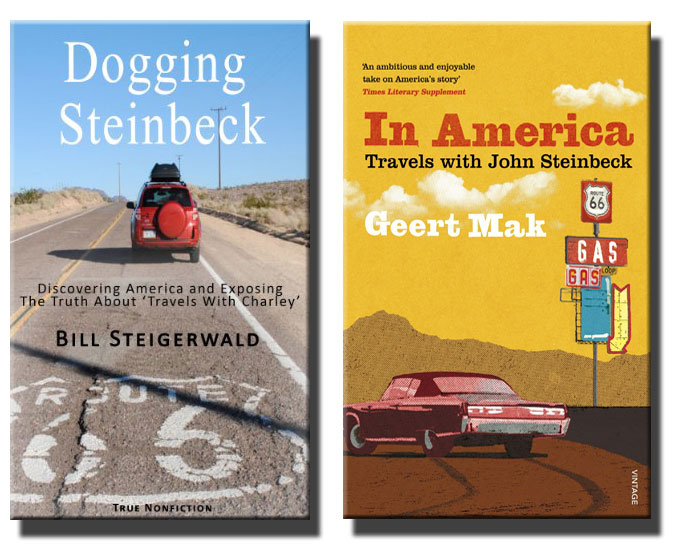

Roosevelt progressivism at both ends of the period covered in America’s West gave Steinbeck the ideals, and events in California the ideas, expressed in The Grapes of Wrath. His upbringing in Salinas gave him the sense of empathy for people, animals, and nature that sympathetic readers recognize and respond to on first reading. When examining the beliefs and behaviors at work in the background, however, it’s also helpful to understand the sense of detachment from events and emotions he had to develop, with changes of subject and venue, in the novel’s aftermath. When he wrote about marine biology or war or the history behind the legend of King Arthur, he had the benefit of distance from his personal past and perceptions. Europeans since De Tocqueville have written about the United States with the same outsider’s advantage that Steinbeck enjoyed in England and David Wrobel has in writing about Steinbeck’s America.

Europeans since De Tocqueville have written about the United States with the same outsider’s advantage that Steinbeck enjoyed in England and David Wrobel has in writing about Steinbeck’s America.

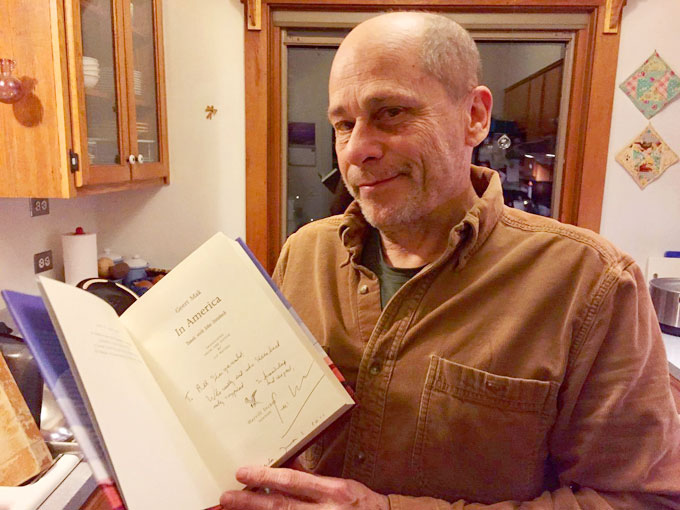

A native of London with a yen for America, David Wrobel brought his coals to Newcastle by enrolling at Ohio University, where he immersed in Steinbeck under Robert DeMott and received his PhD in American studies. His understanding of the history behind The Grapes of Wrath and the intellectual currents of Steinbeck’s time has benefited immensely from his tenure at Oklahoma University, where he teaches, researches, and writes about Steinbeck and the American West and was recently appointed acting dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Oklahoma and California are his coordinates and Steinbeck is his moral compass in the case he makes for America’s West to 1950, the first of two volumes planned by Cambridge University Press. He has the English virtue of readability, along with Steinbeck’s eye for victims and losers, and Cambridge University Press designed the book to last, with just enough charts and graphs and not too many footnotes, placed at the bottom of the page where they belong. Its value is enhanced for followers of Steinbeck’s thinking by the author’s focus on the hidden costs of the West’s ascendancy and the line leading from the triumphalism of the past to the politics of the present. Five stars.

A native of London with a yen for America, David Wrobel brought his coals to Newcastle by enrolling at Ohio University, where he immersed in Steinbeck under Robert DeMott and received his PhD in American studies. His understanding of the history behind The Grapes of Wrath and the intellectual currents of Steinbeck’s time has benefited immensely from his tenure at Oklahoma University, where he teaches, researches, and writes about Steinbeck and the American West and was recently appointed acting dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Oklahoma and California are his coordinates and Steinbeck is his moral compass in the case he makes for America’s West to 1950, the first of two volumes planned by Cambridge University Press. He has the English virtue of readability, along with Steinbeck’s eye for victims and losers, and Cambridge University Press designed the book to last, with just enough charts and graphs and not too many footnotes, placed at the bottom of the page where they belong. Its value is enhanced for followers of Steinbeck’s thinking by the author’s focus on the hidden costs of the West’s ascendancy and the line leading from the triumphalism of the past to the politics of the present. Five stars.

The cover illustration is Thomas Hart Benton’s 1928 Western Regionalist painting “Boomtown.” Of special interest is the section on the Great Depression and the demographic shifts, racial divisions, and labor unrest dramatized in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and In Dubious Battle. It recalls the contributions made to the cause by Steinbeck’s co-workers Dorothea Lange, Carey McWilliams, and Pare Lorentz and explains the epic campaign of Upton Sinclair for governor in 1934 against the same forces that later waged war on The Grapes of Wrath. The author’s essay on California social protest literature, Steinbeck, Sinclair, McWilliams, and the WPA Guide to California appears in American Literature in Transition: The 1930s, an anthology edited by Ichiro Takayoshi.

The cover illustration is Thomas Hart Benton’s 1928 Western Regionalist painting “Boomtown.” Of special interest is the section on the Great Depression and the demographic shifts, racial divisions, and labor unrest dramatized in The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and In Dubious Battle. It recalls the contributions made to the cause by Steinbeck’s co-workers Dorothea Lange, Carey McWilliams, and Pare Lorentz and explains the epic campaign of Upton Sinclair for governor in 1934 against the same forces that later waged war on The Grapes of Wrath. The author’s essay on California social protest literature, Steinbeck, Sinclair, McWilliams, and the WPA Guide to California appears in American Literature in Transition: The 1930s, an anthology edited by Ichiro Takayoshi.