Tom Lorentzen, a retired nonprofit executive in Castro Valley, California, brought John Steinbeck back to life literally on August 24 at a private event billed as “John Steinbeck—in Search of America” and attended by 175 members of a San Francisco Bay Area social club. Impersonating Steinbeck at the age when Travels with Charley and America and Americans were written about a nation rocked by scandal and strife, Lorentzen employed an original idea to dramatize the imaginary conversation of Steinbeck—back from the dead—with Rich, a young logger encountered by the author in an Oregon redwood grove during the fabled road trip across the country from which Steinbeck said he had begun to feel alienated. Now 80, Rich uses a search engine time-travel device to conjure Steinbeck and pose the question he failed to ask when they met in the woods in 1961. What’s so great about America? Lorentzen (in photo) is a former board member of the National Institute of Museum Services. Like Steinbeck, who served on the board that became the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, he remains bullish on America’s future, despite problems that Steinbeck would recognize and acknowledge if, age 115, he were alive today.

Archives for August 2017

Book Signing: Short Stories Based on Steinbeck’s Life

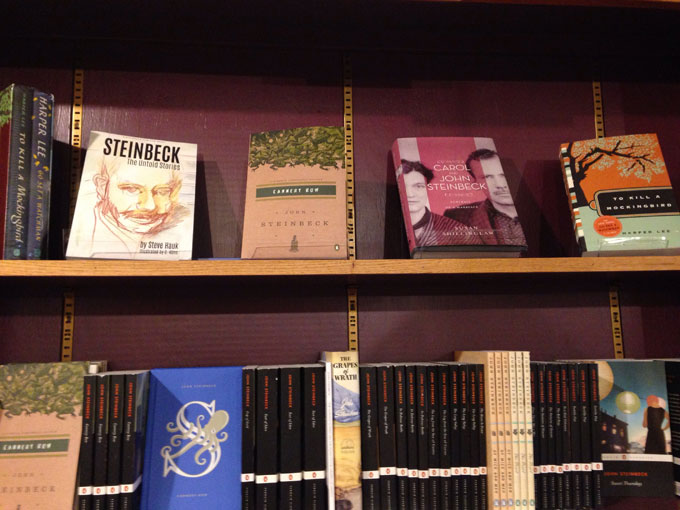

The National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, John Steinbeck’s home town, will host the first official book signing for Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, short stories based on Steinbeck’s life by the playwright and fiction writer Steve Hauk, 5:30-6:30 p.m. on Friday, September 1, in the center’s museum at One Main Street in downtown Salinas. Book news travels fast in Steinbeck country, and Hauk will answer fans’ questions about the origin and inspiration for the stories, which dramatize actual and imagined episodes from Steinbeck’s boyhood and years coping with fame, friends, and enemies in Salinas, Monterey, and New York. Published only one month ago, Steinbeck: The Untold Stories is already on display at the National Steinbeck Center and the Steinbeck House in Salinas, River House Books in Carmel, the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies in San Jose, the Monterey Public Library, and BookWorks in Pacific Grove, the setting for several of the short stories. Common Good Books, the “live local, read large” bookstore associated with Garrison Keillor in St. Paul, Minnesota, also stocks Steinbeck: The Untold Stories.

Photo courtesy of BookWorks.

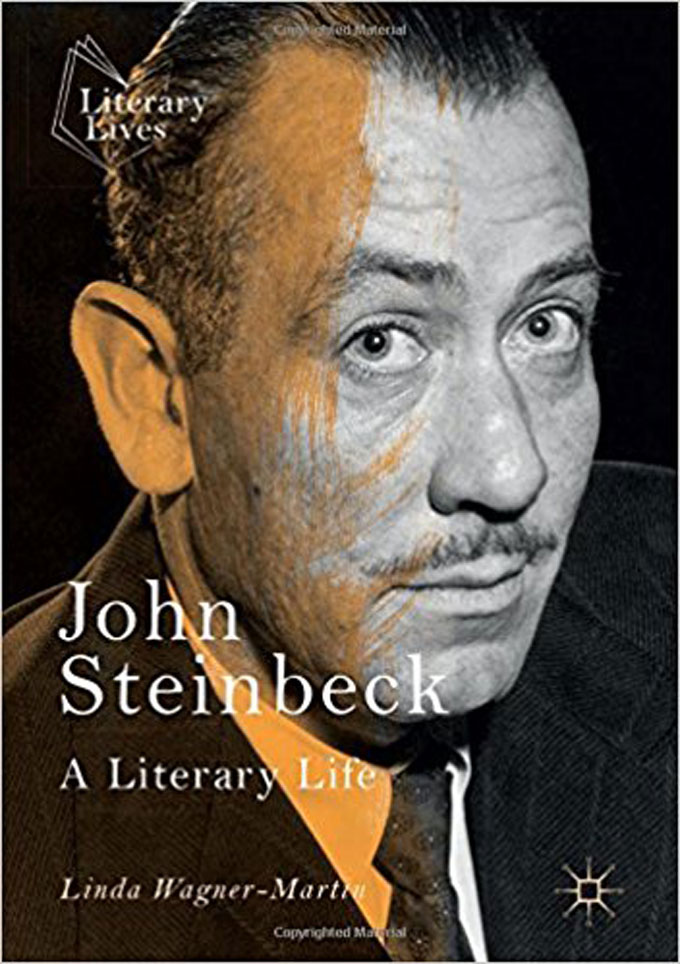

John Steinbeck: A Literary Life, Literary Criticism from Palgrave Macmillan

John Steinbeck: A Literary Life, a book of literary criticism and biography by Linda Wagner-Martin, winner of the Hubbell Medal for Lifetime Service to American Literature, has been released by Palgrave Macmillan, the international academic and trade publishing company. The work is the latest in Palgrave Macmillan’s Literary Lives series. Wagner-Martin, a professor of English and comparative literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, contributed earlier biographies of Emily Dickinson, Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath, and Toni Morrison to Literary Lives, described by Palgrave Macmillan as a “classic series, offering fascinating accounts of the literary careers of the most admired and influential English-language authors.” Chapters include “Steinbeck and the Short Story,” “Journalism v. Fiction,” and “The Ed Ricketts Narratives.” A hardback copy costs $109, the eBook version $85. Individual chapters can be purchased from Palgrave Macmillan in digital form for $29.95.

Stanford University Praises John Steinbeck in Profile of English Prof Gavin Jones

Stanford University—the wealthy private university in Palo Alto, California known for having world-class programs in business, engineering, and medicine—has given a new boost to the literary reputation of John Steinbeck, an erratic English department enrollee who left Stanford in 1925 without a degree. A new online profile of English department faculty member Gavin Jones makes the case for Steinbeck as an undervalued American writer and thinker who was ahead of his time in subject, style, and versatility. “One hundred and fifteen years after his birth in Salinas, California,” the story states, “Steinbeck’s life and work—the latter [of] which has long languished on high school reading lists—is undergoing a revival.” An affable Englishman who recently taught an American studies course at Stanford on Steinbeck and the environment, Jones explains the renewed attraction: “I’d like to think that Steinbeck’s work speaks to students from multiple backgrounds because his interests were so interdisciplinary.” Robert DeMott, the distinguished Steinbeck scholar and poet who also writes about fly fishing, says that Stanford University’s initiative is especially encouraging because Steinbeck teaching and scholarship have traditionally been the province of public colleges such as San Jose State and Ohio University, where DeMott taught generations of graduates including David Wrobel, another English convert to Steinbeck who was recently named interim dean at Oklahoma University. Adds DeMott: “Steinbeck’s recognition by a private university of Stanford’s stature will go far to redress Steinbeck’s underestimation by the literary establishment of his day, and to some extent our own as well.”

Photo of Gavin Jones courtesy Stanford University News Service.

Ku Klux Klan Freak Show in Canon City, 1925: Life Poem

Ku Klux Klan at the Carnival in Canon City, 1925

Klansmen in hooded regalia commandeer a Ferris wheel.

3 to a car, 12 cars. As if visionless hate, rabid nationalism,

and 1st Amendment freedoms share the same carnival ride.

And this isn’t the South. It’s any given Sunday in Colorado.

By an awninged ticket booth, a handful of white sheets loiter.

They’re looking this way as if someone had said, Say, Cheese.

These 40-odd men stare back at our staring as if it’s a nice day

and they have stopped talking Wall Street or Yankees baseball,

whether their wives and daughters should have the right to vote.

Of course there is the fallacy at the heart of democracy that says

when the mob does what it does, it’s right. By simple arithmetic.

A face is said to have hovered over the waters during the creation

of the world. God’s face. If truth were the light certain mornings,

this midway would be a burning cross opening a door in the air.

If an aubade is a morning love song, this Sunday sky isn’t one,

though the noise the Ferris wheel sends up approaches singing.

Factoring in the ubiquity of folly and the capitulation of the sad,

isn’t it always Assholes Get in Free Day somewhere in America?

A Travel Blogger Considers American Self-Identity on a Visit to Salinas, California

The recent visit my wife Elizabeth I made to Salinas, California included a stop at John Steinbeck’s boyhood home. It brought back a flood of memories, and it made me think about self-identity. That felt right in the moment because America’s sense of itself was a major concern of Steinbeck’s writing.

America’s sense of itself was a major concern of John Steinbeck’s writing.

When I was a boy I devoured Steinbeck’s books. By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style. Years later my brother John and I produced travel films and documentaries, and one of the films we made, California: A Tribute, featured a segment on John Steinbeck and the trips to California’s Central Valley that led him to write The Grapes of Wrath. Seeing the Steinbeck House reminded me of the outrage Steinbeck felt about the thousands of dispossessed families from the American Dust Bowl who had made the long trek to California in search of agricultural jobs and a better life, only to find themselves destitute, hungry, and homeless, ready to accept work at any pay so that they could survive and feed their children.

By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style.

On a broader scale, the visit to the Steinbeck House made me think about the course of our nation’s history, about the millions of dispossessed foreigners who came to our shores and borders, fleeing persecution and homelessness and poverty, in search of a better life for themselves and their families, just like John Steinbeck’s American refugees. Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in The Grapes of Wrath—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children, sometimes entire families who have already established themselves in our country. Once upon a time we opened our doors to immigrants. Now we’re closing them.

Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in “The Grapes of Wrath”—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children.

Certainly rules need to be established and followed with respect to immigration. But what is happening now goes beyond rules or regulations. Too many of us are attempting to retreat into a narrow self-identity, building walls against the tide of diversity that has been our distinguishing characteristic as a culture. Who are we as a nation and a people? The comfortable categories of the past are being challenged and shattered in other countries, too, and we feel the same threat to our self-identity that they do. Like John Steinbeck, however, I am optimistic that a new inclusiveness will emerge in the end—the sense of connection and commonality that Steinbeck’s characters achieve in the closing pages of The Grapes of Wrath. The world of the truly human family.

Help SteinbeckNow.com Celebrate Four Years of Celebrating John Steinbeck

This week marks four years of weekly posts at SteinbeckNow.com celebrating John Steinbeck’s life and work, the relevance of his writing to current events, and new art inspired by his enduring fiction. Features posted in August 2013 included new music, visual art, and creative writing, along with a young painter’s reflection on Steinbeck’s artistic impact and a piece about Steinbeck’s home movies by a professional videographer. Other posts discussed Steinbeck’s writing habits, his scrutiny by the FBI, and the connection between the campaign of character assassination waged against Steinbeck in the 1930s and 1940s and the flight of Edward Snowden. Since launching as an independent, noncommercial site serving John Steinbeck’s international fandom, SteinbeckNow.com has published 365 posts that continue the pattern of originality and diversity set four years ago—previously unpublished critical and creative writing, new art and music, and thoughtful commentary from 60 contributors from as far away as North Africa. Along with critical and creative writing inspired by Steinbeck, news items and reviews are also welcome, provided they are original and do not duplicate existing online content. In keeping with its mission, SteinbeckNow.com does accept advertising or pay for material. If you’d like to be in the picture, email williamray@steinbecknow.com.

The Salt Has Kept its Savor For the Reader Who Finds Religious Meaning in John Steinbeck’s Land and People

Although I have read and enjoyed most of John Steinbeck’s published writing, I am not a Steinbeck scholar and claim no special expertise. But I have lived in California’s Monterey County since 1950, and for many years I taught and coached in Salinas, the town where Steinbeck was born, went to school, and found religious meaning attending a local church. In a sense he never left, and my interpretation and appreciation of his work are colored by the land he lived on—the Salinas Valley and the Monterey Peninsula—and the people he wrote about: the poor and “the salt of the earth,” many of whom (to quote the Sermon on the Mount in the King James Version that Steinbeck read) had “lost their savour.”

In a sense Steinbeck never left Salinas or Monterey, and my interpretation and appreciation of his work are colored by the land he lived on and the people he wrote about.

Walking the hills and observing the vistas of Monterey County—from Fremont’s Peak in the Gabilans east of Salinas, to Mount Toro and the Corral de Tierra (the “pastures of heaven” where I now live), to Presidio Ridge in Monterey—these places have affected me deeply as I think they did John Steinbeck. Likewise, looking at the underground Salinas River from the East Garrison bluffs on the site of the former Fort Ord, where Steinbeck may have walked, suggests to me an undercurrent in the lives of the people who have lived on the surface of this land. Unavoidable, and taken for granted in Steinbeck’s time, were the sounds and smells and sights of Monterey Bay, of Cannery Row, of Fisherman’s Wharf, of lower Alvarado Street, of the Rodeo grounds in Salinas during Big Week, which he always enjoyed. Each one added to the grist and flavor of the characters and stories Steinbeck created or recreated in his fiction. I keep coming back to this all-encompassing environment when I read about his characters. These people were close to the earth.

I keep coming back to this all-encompassing environment when I read about his characters. These people were close to the earth.

As an impressionable boy in Salinas, Steinbeck observed poor Mexicans doing stoop labor in the fertile fields of the Long Valley near town, often alongside their children, who should have been in school. This experience prepared him to empathize with the legions of poor Americans looking for jobs in California in the 1930s—with the Dust Bowl farm families displaced by drought and economic depression who populate The Grapes of Wrath, with the unemployed single men moving from ranch to ranch and harvest to harvest in Of Mice and Men and In Dubious Battle.

In the End Melancholy Lifts, Like the Monterey County Fog

During my time teaching and coaching in the schools of Steinbeck’s home town, I interacted with the children and grandchildren of these people. I don’t see “Okies” anymore, but increasingly I do see down-and-out people standing on the corner in downtown Salinas with cardboard signs asking for work or money. The harsh realities faced by rural and small town Americans prior to World War II—the displaced Americans poignantly painted on Steinbeck’s word canvases—seem to have returned. Other vestiges of Steinbeck’s California can be found if one takes the time to walk, look, and listen to the land and the people on whose behalf Steinbeck’s books still bear witness: the emigrants and the immigrants, the homeless and the lonely, the powerless, and those whose lives lack spiritual or religious meaning.

Vestiges of Steinbeck’s California can be found if one takes the time to walk, look, and listen to the land and the people on whose behalf Steinbeck’s books still bear witness.

Read the books, then walk the land—the Monterey County of The Red Pony, Cannery Row, Tortilla Flat, The Pastures of Heaven, Of Mice and Men, East of Eden and The Long Valley; the sister valleys of The Wayward Bus, In Dubious Battle, and To a God Unknown. The living land evoked by Steinbeck largely remains. So does the emotional and thematic undercurrent that runs like a river through the lives of his characters. Many are spiritually, educationally, economically, or socially disadvantaged, unhinged, or bereft. Some find religious meaning. Most do not.

The living land evoked by Steinbeck largely remains. So does the emotional and thematic undercurrent that runs like a river through the lives of his characters.

My reading reveals a human dynamic in Steinbeck’s characters mirroring that of the land they inhabit, sometimes barely: drought followed by flood; summers of suffering followed by winters of discontent; deserts of isolation broken by moments of sustaining humanity that I would call Christian charity. Often melancholy rolls in like the morning fog. But the fog breaks eventually, and Steinbeck’s endings, though rarely happy, always seem hopeful to me.

Day’s End, oil on canvas by Warren Chang, 20” x 30” (2008), courtesy of the artist. ©Warren Chang.

Landscape with a Red Pony, oil on canvas by David Ligare, 32” x 48” (1999), courtesy of the artist. ©David Ligare.

Salinas, California Poetry Slam Invites Submissions

Most Steinbeck books are fiction, but the Salinas, California native also wrote poetry in school and got better grades in versification than he did in short story writing at Stanford. This year’s Big Read poetry slam at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas honors Steinbeck’s gift for verse, and the author’s sensitivity to race and class, with an invitation to writers to compose a poem in response to Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, a 2017 Big Read book selection that reflects on racism in America. This is the fourth year the National Steinbeck Center has participated in the Big Read, a community literacy initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts, but the first to feature a poetry slam—the idea of Jenna Garden, a Stanford student and National Steinbeck Center summer intern. Poems submitted by September 5 will be read aloud to a panel of judges who will award cash prizes on September 8. This year’s Big Read in Salinas, California also features a film series at the Maya Cinemas multiplex. The series kicks off August 28 with Lifeboat, the 1944 movie for which Steinbeck, who wrote the script, did not want credit because of racial stereotyping by the director Alfred Hitchcock, a man Steinbeck privately described as a middle-class English snob.