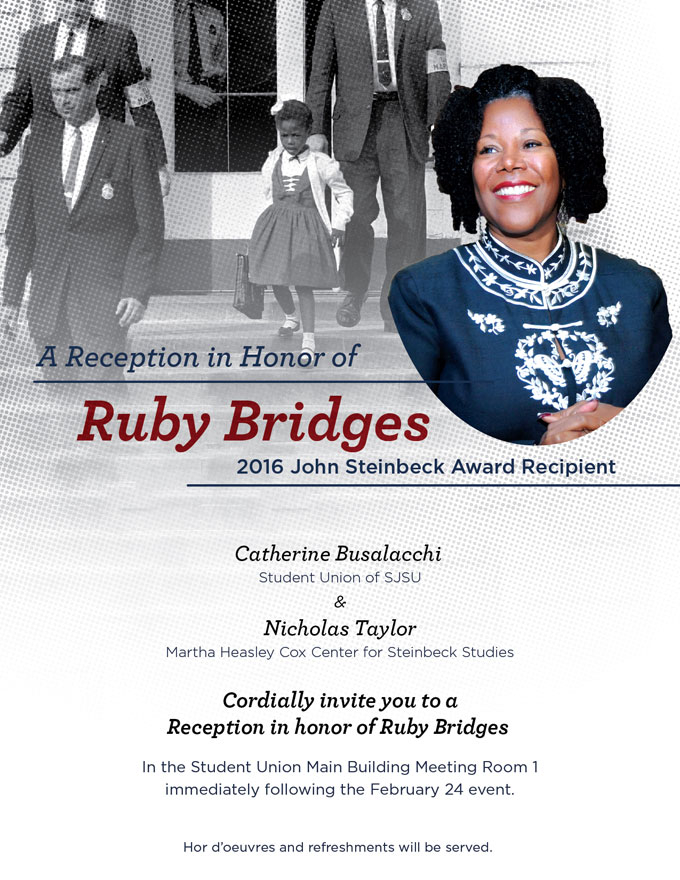

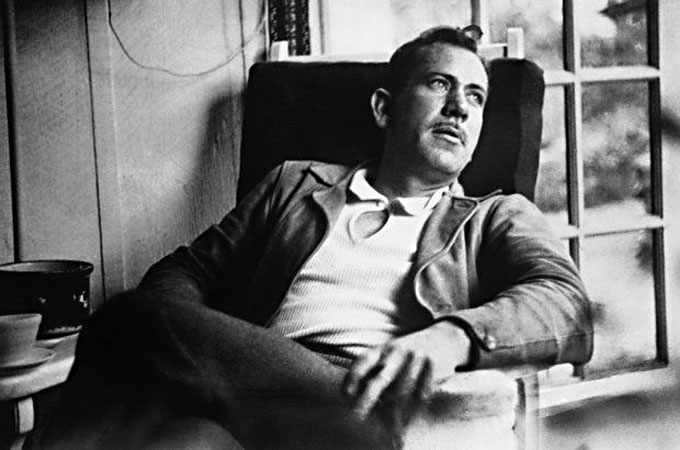

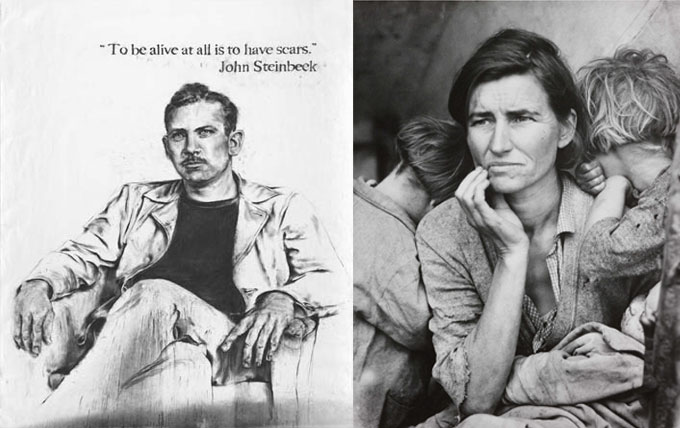

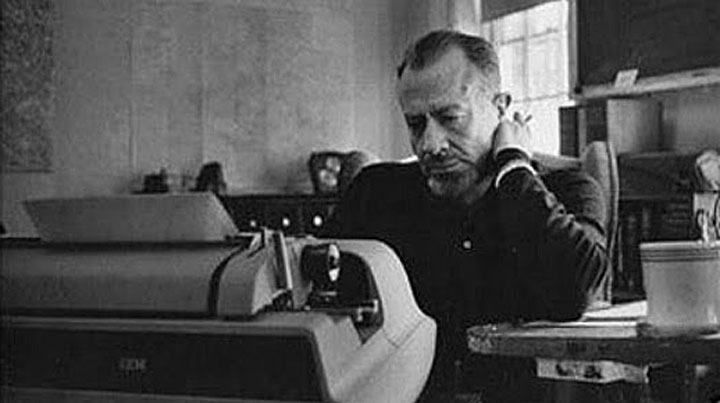

Some walls separate. Others connect. Admirers at San Jose State University have built a handsome wall to commemorate John Steinbeck’s enduring connection with social justice and civil rights, a tie that is celebrated in the John Steinbeck “In the souls of people” Award, given 15 times since 1996 to artists, actors, writers, and activists whose work involves social change. The award ceremony is always a happy occasion, and the February 24 event honoring civil rights leader Ruby Bridges, the brave little schoolgirl described in Travels with Charley, was no exception.

The John Steinbeck award ceremony is always a happy occasion, and the February 24 event honoring Ruby Bridges, the brave little schoolgirl described in Travels with Charley, was no exception.

The Steinbeck award commemorative wall was created by the San Jose University Student Union and is located in the busy student activity building where most award events are held. Explains Nick Taylor, director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University, “The wall consists of a series of disks tracing the timeline of the Steinbeck Award, with background on the rationale for each selection and a few details about each ceremony.” The California civil rights leader Dolores Huerta, an advocate for farm workers’ rights, is a past recipient. Bruce Springsteen received the first award in 1996.

Jim Kent, a member of the John Steinbeck center’s advisory board, traveled to San Jose from Denver for the February 24 event. “As a fan of Travels with Charley,” he said, “I was thrilled to meet the young lady Steinbeck observed as she braved white hecklers during the integration of the New Orleans elementary school where she was the first black student, back in 1960.” A social ecologist who uses Steinbeck in his work empowering citizens to control their own environments, Kent was helping to write federal legislation for Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty when the Civil Rights Act of 1965—which owed much to writers like John Steinbeck—passed Congress. “Ruby Bridges was the perfect choice for this year’s award,” he added. “Like Steinbeck, she is a master storyteller. She attracted a capacity crowd made up of all ages and races, and her elegance inspired five standing ovations. There’s clearly a hunger for continued engagement with civil rights in our time. This was proof.”