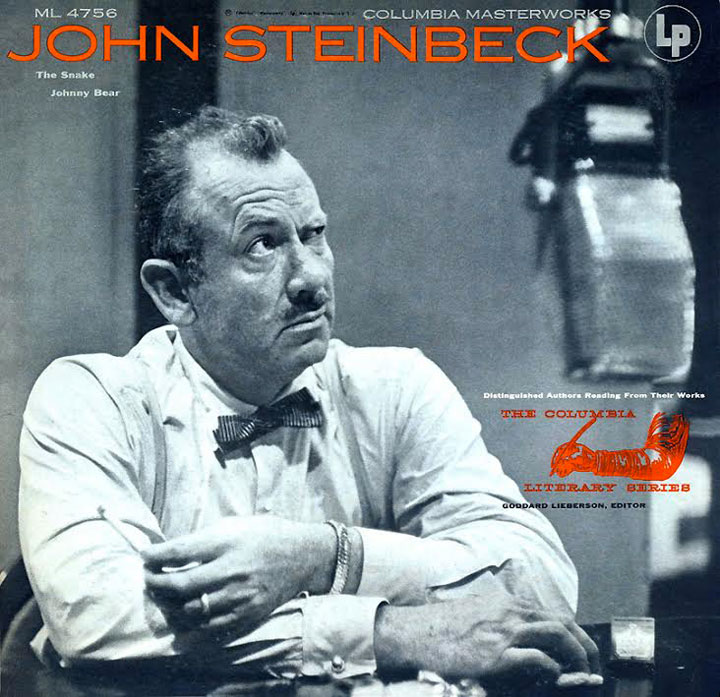

If you follow presidential campaigns, as John Steinbeck did after writing Cannery Row, you’ve probably noticed that candidates like being photographed with regular folks in places where locals gather to meet, talk, and exchange ideas. Coffee shops are a prime example of the phenomenon. In my work with communities facing disruptive change, I seek out these “gathering places,” which exist everywhere—a habit resulting from my long reading of John Steinbeck. Steinbeck’s life and writing are full of local gathering places, beginning with his Cannery Row fiction, set in California. They include the coffee shop on Long Island where he met with old timers when he lived in Sag Harbor, the setting for The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel. As the recent photo of Hillary Clinton in Iowa shows, this year’s presidential campaign is being played out in informal gathering places where “winter” and “discontent” often seem synonymous.

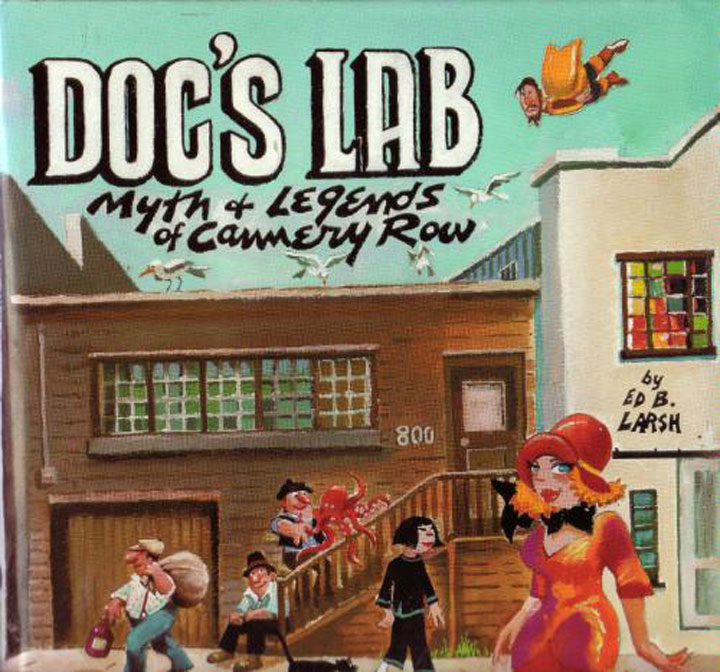

My personal gathering-place journey began 25 years ago with the writing of Doc’s Lab: Myths and Legends of Cannery Row by the late Monterey resident and Cannery Row expert Ed Larsh, a member of the second-owner group that bought Doc’s lab after Steinbeck died. During the phase of research in which I was involved, I discovered a vibrant gathering place in Carmel, California, the town south of Monterey where John Steinbeck spent time at various stages in his California career. What I learned there helped me understand the social ecology of Steinbeck’s gathering places, knowledge that I have applied in my continuing work as a consultant to government and business clients seeking public support (like political candidates) for their plans and aspirations.

The Pine: Gathering Place for Carmel, California’s Artists

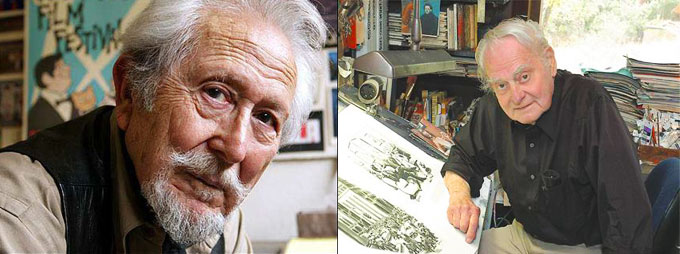

Carmel, California has always had its share of artists, writers, and characters. Two of the most colorful—the syndicated cartoonist Gus Arriola (“Gordo”) and the New Yorker-Playboy cartoonist Eldon Dedini—were part of the Cannery Row circle that Ed Larsh and I needed to interview for Ed’s book about Cannery Row. In those days, if you wanted to meet Gus or Eldon you didn’t make arrangements by phone. Instead, you ventured to the Carmel post office, a gathering place with a storied past, and to The Pine, a coffee shop located a short walk away.

If you wanted to meet Gus or Eldon, you didn’t make arrangements by phone. Instead, you ventured to the Carmel post office, a gathering place with a storied past, and to The Pine, a coffee shop located a short walk away.

Early in the history of Carmel—a bohemian community almost from the beginning—residents decided that houses wouldn’t have street numbers and that mail would be picked up rather than delivered. The Carmel post office became the village center, and a famous gathering place was born. Eldon and Gus would walk to the post office to get their mail at noon, then head for the coffee shop attached to Il Fornaio Restaurant, not far from the nearby Pine Inn. I would show up at the post office at noon, catch Eldon and Gus, and go have coffee where they and their friends gathered—an efficient system that saved the time and trouble of trying to make an appointment, with the added benefit of introducing me to other locals who became part of my network in Carmel.

Early in the history of Carmel, residents decided that houses wouldn’t have street numbers and that mail would be picked up rather than delivered.

Except for a smattering of Carmelites who weren’t artists and tourists staying at the Pine Inn, the coffee shop was sparsely occupied before noon. Starting at 12:00 the pace accelerated, as artists and writers arrived and the tables filled. An outsider, I wondered why people gathered for morning coffee so late in the day; like candidates in presidential campaigns, I usually I go for coffee early in the morning to catch locals I need to meet in new places during the course of my work. Eldon’s answer to my question about Carmel, California’s unusual noontime coffee habit made sense. “It’s foggy and cool here in the mornings,” he explained, “so we artists work in our studios first thing. Once the sun burns off the fog, it’s time to go and get the mail and catch up on the news.” If I wanted to see writers and artists, the best time to go for coffee was 1:00 p.m.

Except for a smattering of Carmelites who weren’t artists and tourists from the Pine Inn, the coffee shop was sparsely occupied before noon. Starting at 12:00 the pace accelerated, as artists and writers arrived and the tables filled.

There is a family-like routine in such places, and Carmel was no exception. Special people had special seats at The Pine, which can be entered from the bar area of Il Fornaio or through a side door from one of Carmel’s charming hidden walkways. R. Wright Campbell, author of the book Where Pigeons Go to Die (made into a movie by Michael Landon), occupied a position along the wall right next to the main entrance. It was his seat at The Pines until he passed away in 2000. Today, an autographed photo of Campbell hangs on the wall above his table, with a plaque bearing his name. Like families, gathering places often honor members with such signs of affection after they’re gone.

There is a family-like routine in such places, and Carmel was no exception. Special people had special seats at The Pine, which can be entered from the bar or through a side door from one of Carmel’s charming hidden walkways.

Most days, Wright would hold court for a couple of hours starting at 1:00. Other writers would join in, too, talking about their projects, offering words of encouragement, and reflecting sympathetically on the problems of publication in a way familiar to John Steinbeck. The advice given and received in this informal gathering of writers would have cost money if provided in a more formal setting, and it came with a valuable support system. Like similar places in Steinbeck’s fiction—notably Doc’s lab in Cannery Row—there was no agenda, no schedule, and no pecking order beyond the respect shown to longevity on the scene. People dropped in, hung out, and interacted, plotting and strategizing together. It was democratic, organic, and free.

Like similar places in Steinbeck’s fiction—notably Doc’s lab in Cannery Row—there was no agenda, no schedule, and no pecking order beyond the respect shown to longevity on the scene.

But there’s a process for accepting new arrivals into the informal networks of most gathering places, and one was observed at The Pine, where newcomers sat at a large round table in the middle of the room—a neutral area—rather than running the risk of taking a regular’s seat at one of the booths. From the chair I occupied at the middle table I could watch and hear the group gathered around Wright Campbell. From time to time I would offer a respectful comment from the edge of the action; after several visits, they made room for me at one of the tables assigned by custom to regulars. Eldon and Gus had vouched for me, and I was in. As Eldon put it, I had become “part of the myth.”

Presidential Campaigns Miss the Point of Gathering Places

The gathering places described in John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row fiction—like the coffee shop he frequented in Sag Harbor, New York, and the one I discovered in Carmel, California— represent epicenters of an informal culture around which people learn from, care for, and communicate with one another spontaneously. They do so without rehearsal, regimentation, or self-consciousness, developing mutual trust over time. Candidates dropping in along the presidential campaign trail in Iowa and New Hampshire may be tolerated at coffee shops, but they never really belong because their presence violates this principle. John Steinbeck understood the inviolable nature of gathering places from experience. I learned much from reading his Cannery Row fiction, and from my own experience in Carmel, California. Today, I have Steinbeck to thank for the core concept that continues to inform my work in communities throughout America: the enduring social ecology of gathering places like Doc’s lab on Cannery Row, the Carmel, California post office, and the coffee shop known as The Pine.

(To learn more about how gathering places can be used to solve major community issues, read about an example in Colorado.)