Like John Steinbeck, the American writer Peter Nathaniel Malae is a rugged realist who insists on honesty. A former Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose State University who grew up in San Jose and nearby Santa Clara, California, Malae spoke candidly about John Steinbeck, American literature, and the life-and-death issues of writing for a living the day after he eulogized Martha Heasley Cox. The memorial event was held in her honor by the Steinbeck studies center she founded at San Jose State University in 1971.

“That Book Saved Me”: On Reading John Steinbeck

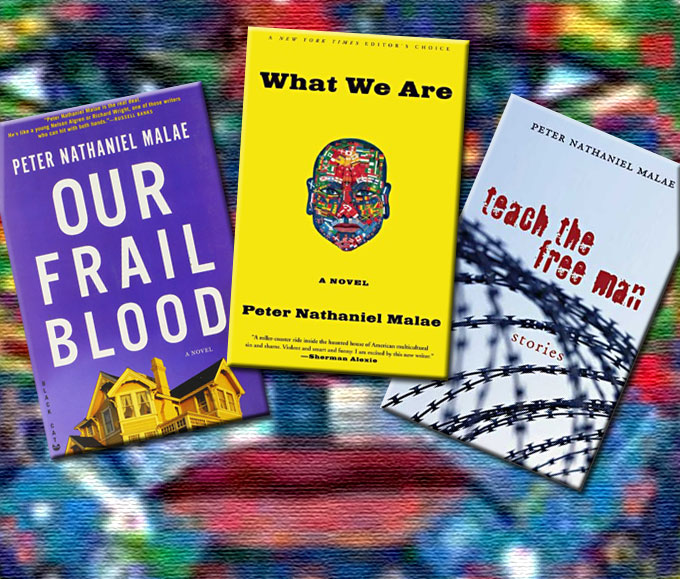

Malae was an inspired choice to represent the 36 creative writers who received Steinbeck Fellow stipends. Teach the Free Man, a collection of Malae’s stories, was published in 2007, the year he was named a Steinbeck Fellow. Two novels published since then—What We Are (2010) and Our Frail Blood (2013)—confirmed Malae’s reputation as a versatile writer who refuses to repeat himself. Like Steinbeck at a similar point in his career, Malae’s output is ambitious: he has already written two more novels, a second collection of stories, two collections of poetry, and a play with a philosophical theme reminiscent of Steinbeck.

Like Steinbeck at a similar point in his career, Malae’s output is ambitious: he has already written two more novels, a second collection of stories, two collections of poetry, and a play with a philosophical theme reminiscent of Steinbeck.

The son of an Italian-American mother and a Samoan father, Malae spent his childhood in a culturally diverse, working-class neighborhood of Santa Clara, squeezed between the city’s “drug-dealing hub”—Royal Court Apartments, Warburton Park, and Monroe Apartments—and the stretch of El Camino Real known as Little Korea for its string of three dozen Korean restaurants and grocery stores running interminably from Santa Clara to Sunnyvale. As a boy, he utilized public transportation on the bus line 22, a tradition kept later as a writer, where he’d composed the bulk of his novel, What We Are, during three-hour rides on the 522, between East Palo Alto and Eastridge Mall in East San Jose.

As a boy, he utilized public transportation on the bus line 22, a tradition kept later as a writer, where he’d composed the bulk of his novel, What We Are, during three-hour rides.

Malae’s father served three decorated combat tours as a tracker with the Special Forces in Vietnam. His uncle Faulalogofie, a Force Recon Marine who’d also fought in Vietnam, was killed by police in Pacifica, California in 1976. His grandfather—the first Samoan minister in America—was a veteran of the Korean Conflict. “I was raised by men who’d had a gang of life-and-death pain in their lives,” Malae says. “But even before they’d ever gone off to war, they’d suffered tremendously. Death, poverty, choicelessness. A weird multigenerational effect of it all is that they basically taught me what to go for in story: they were literary in contradiction. A lot of anger, a lot of third-world violence, yeah, but a lot of third-world beauty, too, a gang of forgiveness.”

‘I was raised by men who’d had a gang of life-and-death pain in their lives,’ Malae says.

Malae attended an exclusive Catholic prep school in San Jose where, like John Steinbeck as a young man, he absorbed the language and rhythm of religious ritual. He read through the Bible for the first time and had his first encounter with Steinbeck in a freshman English composition class. “I loved Tom Joad,” Malae said, “the way he stood up for his family, the way he took it because there was no choice but to take it. I could relate to him. I never told anyone in high school, but I sort of secretly rooted for farmers back then on the sole strength of that image where the tractor comes in and topples the Joad farm.”

‘I loved Tom Joad,’ Malae said, ‘the way he stood up for his family, the way he took it because there was no choice but to take it. I could relate to him.’

Malae went on to play football and rugby at Santa Clara University and Cal Poly, but began getting into serious trouble with the law, having been arrested more than eight times for assault and battery in a two-year span, twice resulting in serious injury. “I was very angry back then. I fought everyone, anyone. Didn’t care how many people I had to fight, didn’t care what the outcome would be. When it comes to growing up tough and angry, I don’t defer to anyone, really. You own it, of course, how you are, but you also became it, shaped by the forces around you.” Within a few years, Malae found himself at San Quentin, where he (again) read through the Bible and started writing 500 words a day—copying Hemingway—on scraps of paper and whatever else was available. “I wrote on the walls, man. I wrote on my arms. The soles of my slippers, as Frost prescribed.”

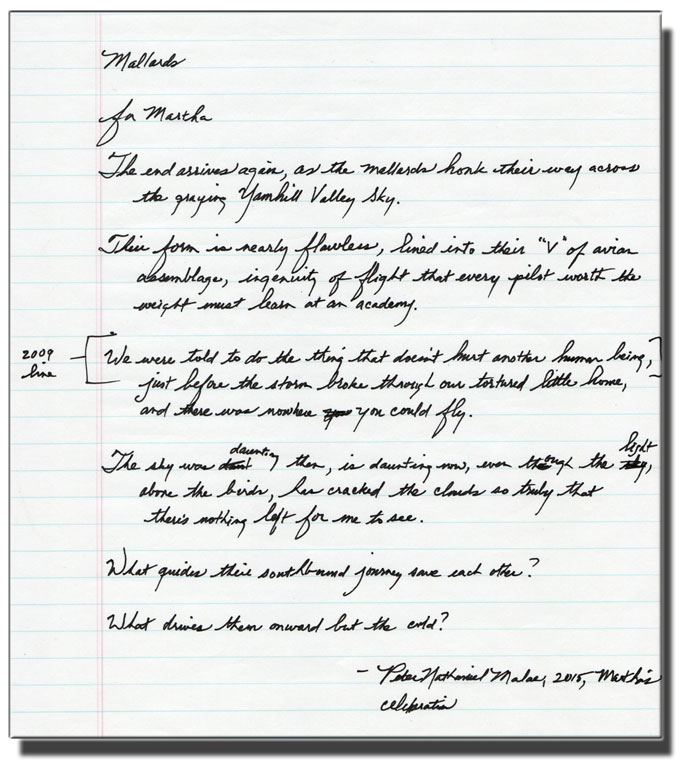

Today Malae writes with a computer, but still revises in longhand, as seen in the manuscript of “Mallards,” the poem he composed in honor of Martha Cox. He thinks that Steinbeck, a pencil-lover who eventually adapted to the typewriter, would like the cut-and-paste convenience of computers. But he dislikes social media, email, and texting, inventions that he says increase social isolation and divorce users from life-and-death reality. On the train to San Jose he worked on a new novel, observing “human beings in their essence and element,” akin to Steinbeck’s claim of being a shameless magpie, taking to the fields with paisanos.

On the train to San Jose he worked on a new novel, observing ‘human beings in their essence and element,’ akin to Steinbeck’s claim of being a shameless magpie, taking to the fields with paisanos.

In prison Malae discovered The Pastures of Heaven, which he’d read in Spanish (Las Pasturas del Cielo). He described the experience with Steinbeckian irony in “The Book is Heavenly,” an award-winning essay published in South Dakota Review (Vol. 41, No. 1 and 2):

The book became my paperback talisman of hope. Something I could rely on in the unreliable undercurrent of prison life. . . . On the Catholic calendar distributed to us during Christmas, my reading list for the months of March, April and May 1999 were: The Catch-Me Killer, Bob Erler, and then fourteen straight readings of The Pastures of Heaven, John Steinbeck. . . . It kept me sharp and focused, reminded me of what once was and what, of course, could be again. That book saved me.

“Realism in the Craft”: On Writing American Literature

Malae’s first novel, What We Are (the title comes from a quatrain by Byron), explores life and death in the dark corners of contemporary society that few writers of American literature have exposed with comparable sharpness or skill. The narrative is a journey of adjustment, to anomie and estrangement, by a sensitive, angry character who learns, as Malae himself believes, that “our story is a life and death thing.” Our Frail Blood, his second novel (the title comes from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night), is as different from What We Are as East of Eden is from Cannery Row. In alternating plot lines, the book encompasses three generations of California life in which children and grandchildren pay for the secret sins of fathers, brothers, and sons. The family epic unfolds through the eyes and actions of fully developed female characters who bring unity, resolution, and redemption to the story, like Steinbeck’s women in The Grapes of Wrath. Malae cites East of Eden, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and Francis Ford Copolla’s Godfather II as narrative forebears in scope and theme.

The narrative of Malae’s first novel is a journey of adjustment, to anomie and estrangement, by a sensitive, angry character who learns, as Malae himself believes, that ‘our story is a life and death thing.’

The Question, Malae’s most recent work, is his foray into the world of theater. The story dramatizes the struggle of a Hispanic ex-boxer and convict to answer the existential question asked by his eight-year-old son: “Why do people kill other people?” Malae says the idea for the play—and the question it poses—occurred to him at San Quentin in 1999, when Manuel “Manny” Babbitt, a veteran of the Vietnam War with a Purple Heart for heroism, was executed. Babbitt, a Marine, was wounded at the Battle of Khe Sanh in 1968; he received the death sentence in 1980, before post-traumatic stress disorder was understood as a consequence of contemporary warfare. Manny Babbitt’s last words were “I forgive you all”; at the end of The Question, Malae’s character tells his son that he can’t say why people kill other people—but “I know why people save other people.”

Malae says the idea for his play—and the question it poses—occurred to him at San Quentin in 1999, when Manuel ‘Manny’ Babbitt, a veteran of the Vietnam War with a Purple Heart for heroism, was executed.

Intense, thoughtful, and articulate, Malae worries about the overpopulation of modern American literature by writers trained in college MFA programs, 360 in number at last count. “They teach writers that the creation of story is a democratic roundtable or assembly line. Which can eradicate the soul of the work. Since art is about desperation, the last thing you want infecting your work is conformity. And then as you pay a fee for a service, the natural tendency is to expect that you get what you paid for. The daily struggle with the craft doesn’t abide that ethic. Sometimes it barely abides you. Sometimes you get nothing.” Steinbeck, too, championed what Malae calls “realism in the craft” forged by fierce aesthetic individualism.

Steinbeck, too, championed what Malae calls ‘realism in the craft’ forged by fierce aesthetic individualism.

Malae described the connection he feels with American literature of John Steinbeck’s century in an interview with Oregon Literary Arts after winning the drama fellowship for The Question:

I’m with O’Connor and Faulkner and a whole horde of other dead masters who describe the deal in terms of a blue-collar work ethic. I see the creative process as merely this, a dress-down of self that more or less occurs daily: do you have the balls to call yourself a “writer”? Well, then, “put the posterior in the chair,” as my freshman comp teacher used to say; “don’t talk,” as Hemingway advised, and handle your business.

Paul Douglass, the San Jose State University English professor who managed the Steinbeck Fellows program from 2000 to 2013, notes that Malae’s 2007-2008 class was “outstanding.” He recalls reading the untitled manuscript of What We Are when Malae’s name was first submitted, and being impressed. After finishing his fellowship, Malae continued to correspond with Martha Cox, a shrewd reader and enthusiastic patron. In his remarks at her memorial he recalled visiting her modest San Francisco apartment, crowded with “classics of American literature” by some of his favorite authors. He was humbled, he said, to see a copy of Teach the Free Man, read and annotated, on her shelf.

Excellent profile of one of the most exciting American writers working today. The last line really gets me, because the stories in TEACH THE FREE MAN are set in prisons, work-release programs, and other settings Martha Cox probably never experienced first hand. Yet she devoured the book. I can’t think of a better tribute to the power of literature to bond humans. And I love the reference to Martha’s notations. In my office I have many of her tattered paperback editions of Steinbeck. Every yellowed page is covered with her marginalia. It occurs to me that for Martha, reading may have been what writing is to Peter Malae: “a dress-down of self that more or less occurs daily.”

Another wonderful read at SteinbeckNow.com. Thank you. Just a couple thoughts: (1) The idea of the children and grandchildren paying for the sins of the father/grandfathers is patently Jungian especially if understood from both the conscious and unconscious influence; and (2)you cannot appreciate the concept of the “individual” based upon the ideas of operant conditioning and behaviorism. A study of the center of a bell curve will not prepare anyone to understand the characteristics at the extremes. Yet, for the most part, Jung is ignored in psychology curriculum. Thank God Steinbeck knew better.

That is a very good point about Jung. Because certain philosophers achieved a kind of hyper-popularity in one period–one thinks of Freud, Jung, Bergson, Sartre–we act as if we have outgrown them, when in reality we missed knowing them in their true, raw, unpopularized forms. Steinbeck was sympathetic to ideas that had what William James called “cash value,” and not because he belonged to a school or coterie. Perhaps this is one reason that when we read about “Modernism,” we rarely hear Steinbeck’s name mentioned?