Anyone alive at the time always remembered the day John Kennedy died. John Steinbeck and his wife Elaine were in Warsaw on a U.S. cultural mission and helped embassy personnel deal with a flood of well-wishers while grieving quietly, inwardly, through the long November night. Though the John Kennedy-John Steinbeck bond was never as close as Steinbeck’s friendship with Adlai Stevenson, the previous Democratic presidential nominee, Steinbeck admired Kennedy’s warmth, wit, and wonderful way with words. It was the respect of one wordsmith for another, and it led to Jackie Kennedy’s suggestion that John Steinbeck write John Kennedy’s official biography.

Anyone alive at the time always remembered the day John Kennedy died. John Steinbeck and his wife Elaine were in Warsaw on a U.S. cultural mission and helped embassy personnel deal with a flood of well-wishers while grieving quietly, inwardly, through the long November night. Though the John Kennedy-John Steinbeck bond was never as close as Steinbeck’s friendship with Adlai Stevenson, the previous Democratic presidential nominee, Steinbeck admired Kennedy’s warmth, wit, and wonderful way with words. It was the respect of one wordsmith for another, and it led to Jackie Kennedy’s suggestion that John Steinbeck write John Kennedy’s official biography.

John Steinbeck: Stevenson in ’52, ’56, and ’60!

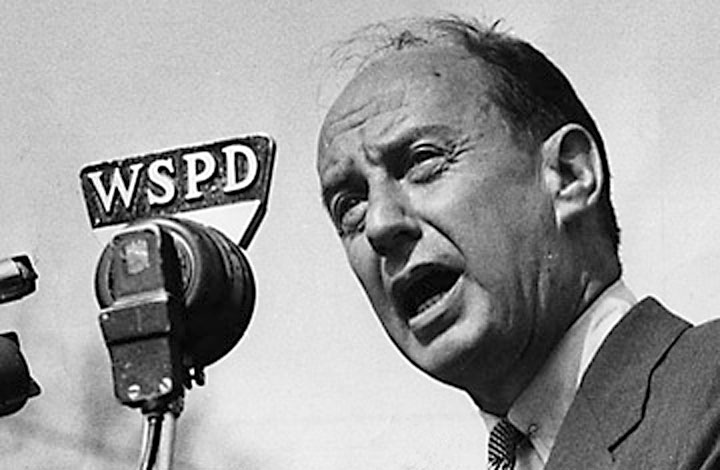

A staunch New Deal Democrat with small town Republican roots and a record of wartime advice and service to his hero Franklin Roosevelt, Steinbeck had little to say publicly about Harry Truman, FDR’s successor. But he didn’t hold back when Eisenhower and Nixon emerged. He thought Ike was tongue-tied, under-informed, and unqualified to be president. How could anyone who mangled syntax and read westerns for entertainment possibly be fit for the White House? Nixon he deeply disliked and distrusted for reasons that proved prophetic. In the 1952 presidential election, Steinbeck supported Adlai Stevenson, but he didn’t meet Stevenson until the Democratic convention he covered as a special reporter in 1956.

Jackson Benson, John Steinbeck’s principal biographer, described the opening act of Steinbeck’s long-running friendship with Stevenson in The Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer:

Jackson Benson, John Steinbeck’s principal biographer, described the opening act of Steinbeck’s long-running friendship with Stevenson in The Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer:

From the time of this meeting, the Steinbecks and Stevenson became close friends, visiting each other often in the years that followed. At the convention, Stevenson grabbed Steinbeck, pulled him into a little room, and said “Sit down. I need a drink.” The two sat talking for half an hour, John telling him of the humorous things he had heard on the floor. Every time he got up to go, Stevenson asked him to stay. It was the first time in days, Stevenson told him, that he had had a chance to relax.

John Steinbeck, who disliked funerals, attended Stevenson’s service in Ilinois in 1965. In 1960 he had hoped his friend would run again, this time against Dick (“I liked him better when he was a mug”) Nixon, adding his name to a list of celebrity authors and academics advocating for Stevenson over Kennedy, the Democrats’ rising star. But the charismatic young Senator from Massachusetts—the home state of Steinbeck’s paternal grandparents—swept the spring primaries and won the American presidency by a Chicago hair. Kennedy was Catholic, a writer, and a war hero, appealing qualities. The Steinbecks supported his campaign and were invited to his inauguration.

John Kennedy’s Inauguration and its Endless Invocations

John Kennedy once described Washington as combining Southern efficiency with Northern charm. He might have mentioned Southern humidity and Northern winters as well. The 1961 inauguration was marred by one of Washington’s worst snowstorms; while Kennedy’s acceptance speech warmed John Steinbeck’s heart, Elaine’s feet were freezing. In a section of the manuscript omitted from Travels with Charley when it was published, Steinbeck recorded the event with epic hilarity. (Given Kennedy’s constant back pain from disease and injury, Steinbeck’s reference to women’s “backache” seems especially ironic. Today we know more about Kennedy’s medical condition than anyone admitted at the time.)

I got us to our seats below the rostrum of the Capitol long before the ceremony—so long before that we nearly froze. Mark Twain defined women as lovely creatures with a backache. I wonder how he omitted the only other safe generality—goddesses with cold feet. A warm-footed woman would be a monstrosity. I think I was the only man who heard the inauguration while holding his wife’s feet in his lap, rubbing vigorously. With every sentence of the interminable prayers, I rubbed. And the prayers were interesting, if long. One sounded like general orders to the deity issued in a parade ground voice. One prayer brought God up to date on current events with a view to their revision. In the midst of one prayer, smoke issued from the lectern and I thought we had gone too far, but it turned out to be a short circuit.

John Kennedy—a Catholic in the same way that John Steinbeck was an Episcopalian, nominal and not by choice—secretly agreed with Steinbeck about the endless prayers. Below the official text of the letter sent to the “distinguished artists who were kind enough to be in Washington,” Kennedy provided a handwritten critique of the episode for Steinbeck’s private enjoyment: “No President was ever prayed over with such fervor. Evidently they felt that the country or I needed it—probably both.” Two witty Johns joined at the funny bone, sharing the same artery to America’s master of irreverence, Mark Twain. As quoted in Steinbeck: A Life in Letters (edited by Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten), John Steinbeck enlarged on the tale, which grew in height over time:

John Kennedy—a Catholic in the same way that John Steinbeck was an Episcopalian, nominal and not by choice—secretly agreed with Steinbeck about the endless prayers. Below the official text of the letter sent to the “distinguished artists who were kind enough to be in Washington,” Kennedy provided a handwritten critique of the episode for Steinbeck’s private enjoyment: “No President was ever prayed over with such fervor. Evidently they felt that the country or I needed it—probably both.” Two witty Johns joined at the funny bone, sharing the same artery to America’s master of irreverence, Mark Twain. As quoted in Steinbeck: A Life in Letters (edited by Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten), John Steinbeck enlarged on the tale, which grew in height over time:

I had never seen this ceremony. I found it very moving when they finally got through the prayers to it. As Elaine says, most ministers are hams but they haven’t learned the first rule of the theatre—how to get off. When [Cardinal] Cushing got to whumping it up I thought how I’d hate to be God and have him on my tail. The good Cushing didn’t ask, he instructed; and I bet he takes no nonsense from the Virgin Mary either nor from the fruit of her womb, Jesus.

But the young president’s address was stirring, and Steinbeck was more than moved. He admired Kennedy’s speech like a writer, for style as much as substance. The reason for his respect became the punch line of a literary joke, delivered dead-pan to reporters looking for a scoop about Steinbeck. Benson’s biography explains that the author answered their questions about the Steinbecks’ visibility around Washington with the same kind of humor shown by Kennedy in private:

But the young president’s address was stirring, and Steinbeck was more than moved. He admired Kennedy’s speech like a writer, for style as much as substance. The reason for his respect became the punch line of a literary joke, delivered dead-pan to reporters looking for a scoop about Steinbeck. Benson’s biography explains that the author answered their questions about the Steinbecks’ visibility around Washington with the same kind of humor shown by Kennedy in private:

Since he was [at the inauguration] and receiving all this attention, Steinbeck was assumed by some in the press to be up for some job in the administration. When he was asked, on one occasion he said that he had been named Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, but he had not yet got his uniform fitted. To others, he replied that he was the new Secretary of Public Health and Morals and Consumer Education. When asked his reaction to the inaugural address, he said, for the television audiences, “Syntax, my lad. It has been restored to the highest place in the Republic.”

Syntax—high praise for any politician, and music to Steinbeck’s ears after the painful atonality of the Eisenhower era.

Kennedy’s Assassination and Steinbeck’s Refusal

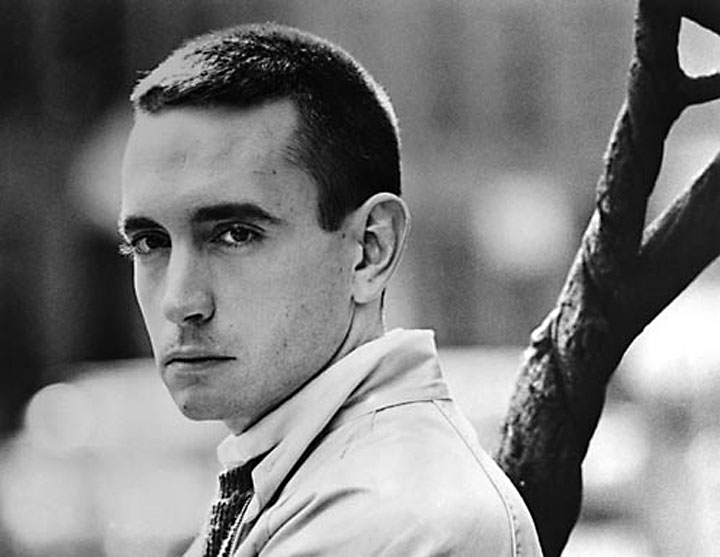

Following the inauguration John Steinbeck and John Kennedy met several times, and Steinbeck was later selected to receive the Medal of Freedom—an honor the President would not live to bestow. In the spring of 1963, the author and his wife accepted the invitation to travel behind the Iron Curtain as cultural emissaries for the high-culture administration where a francophone First Lady set a sophisticated European tone. Remarkably, in retrospect, Steinbeck insisted that another writer accompany them: Edward Albee, the young creator of the biting Broadway stage hit, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee was acerbic, audacious, and gay; his sharp-edged play lacerated marital monogamy and introduced audiences to vocabulary formerly reserved for the drill field. Hard to believe today, but Steinbeck’s demand was granted and the trip to the Soviet bloc took place as planned, Albee (below) included.

The Steinbecks had reached Poland when they heard the news from America on November 22. Jay Parini quotes Elaine’s version in John Steinbeck: A Biography:

The Steinbecks had reached Poland when they heard the news from America on November 22. Jay Parini quotes Elaine’s version in John Steinbeck: A Biography:

“That was a day none of us would ever forget,” says Elaine. “John and I had just gotten back to Warsaw when the news broke on the radio that John Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. The first report was that he was wounded, and we were horrified. Then we heard he was dead. It was so moving what happened: the Poles all surrounded us and hugged us, saying how sorry they were to hear this terrible, terrible news [and we] needed time to mourn. We called the State Department, and they suggested that we go to Vienna for a few days. There was a funeral service for Kennedy at the cathedral there. It was a memorable and moving day.”

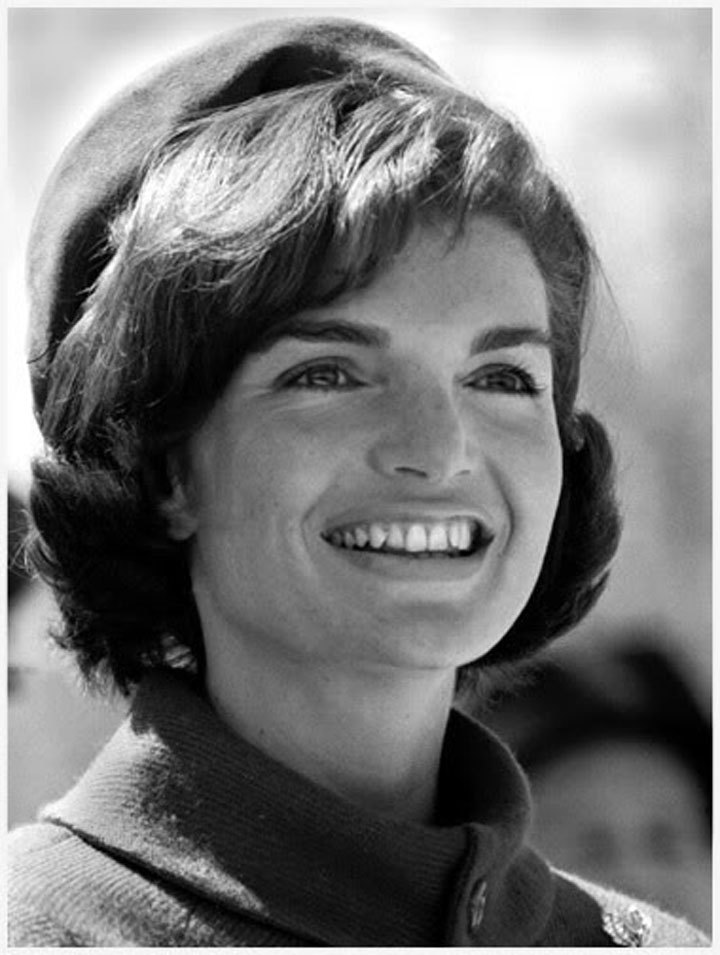

Cutting short their itinerary, the Steinbecks returned to Washington for debriefing by the State Department over three days in late December, precisely five years before Steinbeck would die in New York at the age of 66. The Steinbecks’ letter of sympathy to Jackie Kennedy, written a few days earlier, received a surprising response from the former First Lady. Benson explains:

In the meantime, [Mrs. Kennedy] wanted someone to write a definitive biography of her husband, and she had thought Steinbeck the writer most suitable. She got in touch with mutual friends and made some inquiries and then wrote the Steinbecks to come see her in Washington. When John and Elaine called on her, they could see that, although she had herself under control, she was still obviously in a state of shock. She talked to them about the kind of book she had in mind and very openly and movingly about the President and about her relationship to him. At one point Elaine began to cry, and Mrs. Kennedy said, “Please, Elaine, if you must cry, go to the bathroom and pull yourself together. I can’t bear it now, and I’ll go to pieces.” Their visit stretched into a stay of several hours, as every time they started to leave, Mrs. Kennedy would beg them to stay—“I’ve nothing in the world to do.”

After careful consideration and more meetings, John Steinbeck declined Mrs. Kennedy’s suggestion that he write her husband’s book. As Benson observes, “what he had in mind does not seem to have been an orthodox biography.” Steinbeck never produced his planned autobiography either, and for much the same reason. Writing to his college friend Carlton Sheffield a few days before the February meeting with Mrs. Kennedy, Steinbeck said that if he ever wrote his own life story he wanted to make it a “real one”—“since after a passage of time I don’t know what happened and what I made up, it would be nearer the truth to set both down.” As Benson suggests, the novelist “never found solutions to the problems of form presented” by factual biography. In April he gave Mrs. Kennedy his answer—not now: “One day I do hope to write what we spoke of—how this man who was the best of his people, by his life and death gave the best back to them for their own.”

After careful consideration and more meetings, John Steinbeck declined Mrs. Kennedy’s suggestion that he write her husband’s book. As Benson observes, “what he had in mind does not seem to have been an orthodox biography.” Steinbeck never produced his planned autobiography either, and for much the same reason. Writing to his college friend Carlton Sheffield a few days before the February meeting with Mrs. Kennedy, Steinbeck said that if he ever wrote his own life story he wanted to make it a “real one”—“since after a passage of time I don’t know what happened and what I made up, it would be nearer the truth to set both down.” As Benson suggests, the novelist “never found solutions to the problems of form presented” by factual biography. In April he gave Mrs. Kennedy his answer—not now: “One day I do hope to write what we spoke of—how this man who was the best of his people, by his life and death gave the best back to them for their own.”

John Steinbeck’s Arthur and John Kennedy’s Camelot

Steinbeck didn’t invent the Camelot trope for the Kennedy years, but as a serious student of Arthurian literature he could use it convincingly. When read today, the letter he wrote Mrs. Kennedy after their initial meeting about her husband’s book is—in its poetry, power, and prescience—better than “an orthodox biography” could ever be:

The 15th century and our own have so much in common—loss of authority, loss of gods, loss of heroes, and loss of lovely pride. When such a hopeless muddled need occurs, it does seem to me that the hungry hearts of men distill their best and truest essence, and that essence becomes a man, and that man a hero so that all men can be reassured that such things are possible. The fact that all of these words—hero, myth, pride, even victory, have been muddled and sicklied by the confusion and permission of the times only describes the times. . . .

Steinbeck wrote the closing moral trilogy of his career—The Winter of Our Discontent, Travels with Charley, America and Americans—in the reflected light of Kennedy’s Camelot and the sudden shadow that fell across America following his death. I wonder. Has it occurred to others that John Steinbeck died so soon after the abdication of his friend Lyndon Johnson and the election of Richard Nixon in 1968? Death spared Steinbeck the Watergate scandal, Reaganism, and the retrograde racism of today’s insurgent Tea Party. Surely he would have detested and denounced each, not merely for mendacity, but also for lacking any trace of Kennedy’s intellect, warmth, or wit.

The quality of educated humor went out of the body politic with the death of John Kennedy, and I think Steinbeck knew it as it was happening. His most memorable epitaph for the elegant president who joked with him, Twain-like, about priests and public prayers appears near the end of the letter just quoted. Fifty years after John Kennedy’s assassination, John Steinbeck’s words of comfort to the slain president’s widow still thrill with hope for the return of an American Camelot:

At our best we live by legend. And when our belief gets pale and weak, there comes a man out of our need who puts on the shining armor and everyone living reflects a little of that light, yes, and stores some up against the time when he has gone. . . .

.

Oh, William. I read this and didn’t realize you wrote it. I am so touched. What a wonderful tribute to two great men. I am sending it to my closest friends and family members. Thank you so much.

Wayne

Will–

As you write, Steinbeck admired Kennedy’s “warmth, wit, and wonderful way with words.” Unable to hide my own admiration for your work, I will recommend to one and all this scholarly and stylish contribution to ’60s history. You too command the 3Ws!

Joe

Thank you both for your very kind words. I was exiting my freshman music theory class at Wake Forest when I heard the news over the loudspeaker located outside the campus bookstore on the Quad that day. Years later I had the chance to serve as organist at Edward’s, “the Kennedy church” in Palm Beach, where some parishioners’ memories were still very much alive about Rose Kennedy’s faithful attendance at daily mass when she was in residence at the family compound on North Ocean Blvd. The property, which I got to tour before it was sold, was eventually purchased by John and Marianne Castle, who also became stalwarts of St Edward’s. Seeing John Kennedy, Jr. on the street in Palm Beach once afternoon was a thrill, and my friend Laurence Leamer wrote several books about the family, so my feelings about JFK are particularly personal. I hope that yours are as well. An era of hope and, in a sense, of American innocence ended 50 years ago today. As i tried to suggest, I think John Steinbeck felt the loss deeply and in his own way never recovered. “Let us now praise two famous men . . . .” I’ve had my say. Other readers are now warmly invited to share their thoughts.

Your writing evokes so many emotions about the past and also so much hope for what we can accomplish when our leaders are well-informed readers and curious learners. Thank you for writing so majestically about the country’s past.

Thank you. For those who may not know her personally or by reputation, Lisa Vollendorf is the dynamic new dean of the College of Arts and Humanities at San Jose State University.

In a letter to Adlai Stevenson, Steinbeck wrote:

I want to be Ambassador to Oz. Don’t smile that way, please. Glinda the Good has a mirror which makes all of our listening and testing devices obsolete. I don’t know whether I could bring Oz into NATO right away, but at least the U.N. might benefit by its membership. You will remember also that the Wicked Witch melted and ran down over herself. If I could get that secret, we could handle quite a few people who would look better melted down.

– Steinbeck: A Life in Letters. Adlai Stevenson, January 1962, 692